“Photography and film may differ,” wrote the distinguished curator Felix Hoffman recently, “yet in their imagery and narrative styles, the two media have much in common.” Three American media agnostics whose careers as filmmakers and photographers spanned the course of the 20th century—Paul Strand, Helen Levitt, and Gordon Parks— exemplify the cross-pollination between the two media.

Paul Strand

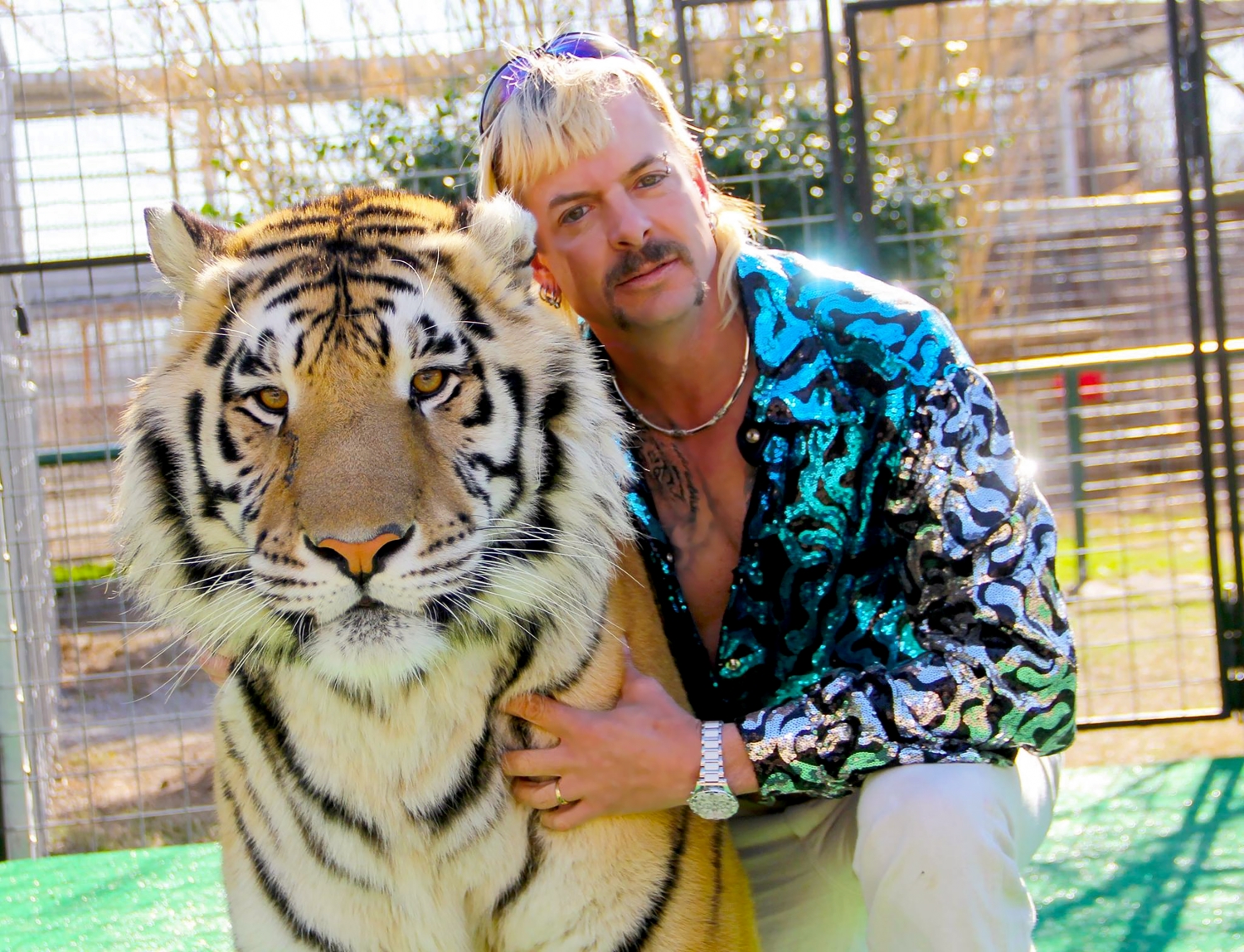

In 1921, Paul Strand (1890–1976), already well known as an art photographer, made the short film Manhatta in collaboration with painter Charles Sheeler. The 12-minute film begins with a poem by Walt Whitman that proclaims: “City of the world / (for all races are here) / City of tall facades / of marble and iron, / Proud and passionate city.” Strand captures the spirit of these words by portraying the city with high-angle and graphic shots that convey the monumentality of the skyscrapers.

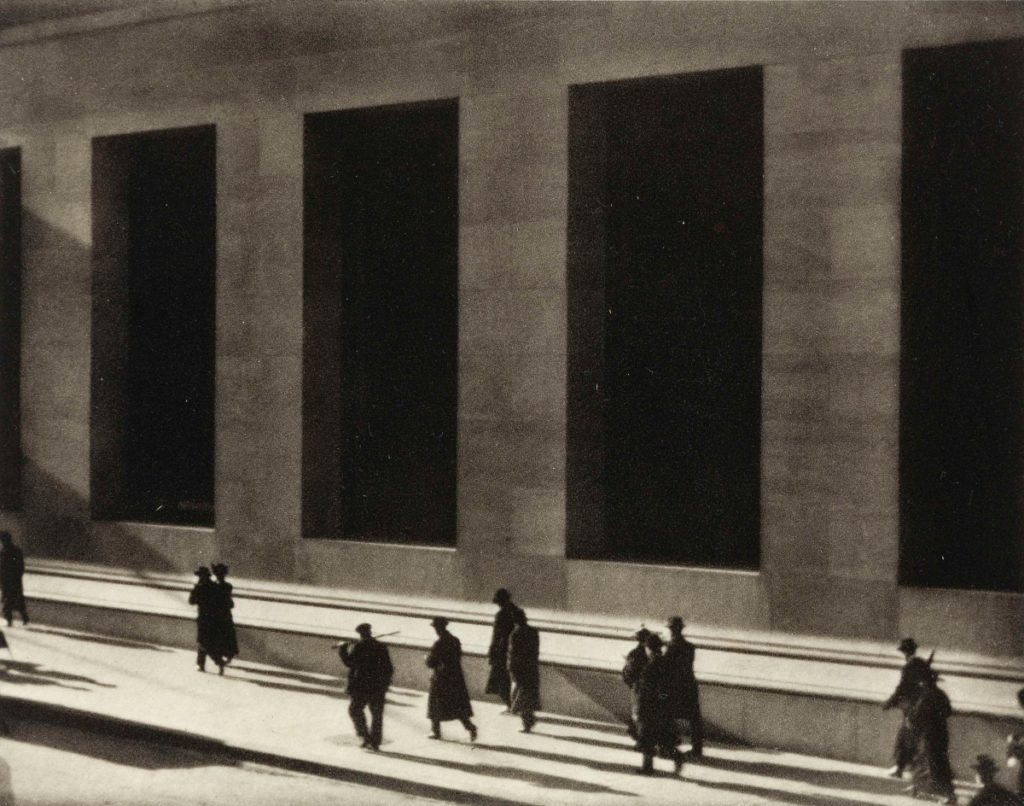

The film’s cinematography reflects the modernist style of Strand’s photographs. In particular, his iconic photograph Wall Street, made in 1915, could almost be a single frame taken from the movie. In the photograph, pedestrians are reduced to mere shadows by the imposing façade of the J.P. Morgan Building. Crystal-sharp from edge to edge, the photograph reflects Strand’s striving for “absolute, unqualified objectivity.” The film’s “towering geometry” is in much the same style.

After the success of Manhatta, Strand earned his living from filmmaking for decades, only photographing sporadically. In the early 1930s he was invited by the Mexican government to make a series of films on the people of their land. He welcomed the radical cultural climate that was the legacy of the Mexican revolution of 1910–17, and shared Mexican artists’ belief that the “ideal goal of art … should be one of beauty, education, battle.” Only one film was made: Redes (which means “fishing nets,” though the film was released as The Wave in English). Directed by Fred Zinnemann, it was written and photographed mostly by Strand, who wrote in a letter in 1935 that, “not only the photography is mine, but its spirit and conception.”

Redes is a classic story of struggle and triumph in which the residents of a fishing village fight back against their exploitation by fish buyers in collusion with corrupt politicians. Strand used local villagers (except for one actor) to play themselves in a dramatization of their own plight, and to represent the universal struggle of fishermen across Mexico. His technique was to fragment a scene into a series of powerfully composed shots of the individual fishers’ faces and arms as they rowed or pulled nets, watching the hopelessness in their faces give way to a collective sense of triumph. In fact, Redes seems to consist of almost-still photographs transformed into film, to the point that Zinnemann complained that “…[Strand] saw films as a succession of splendid but motionless compositions while I was trying to get as much movement into scenes as possible.”

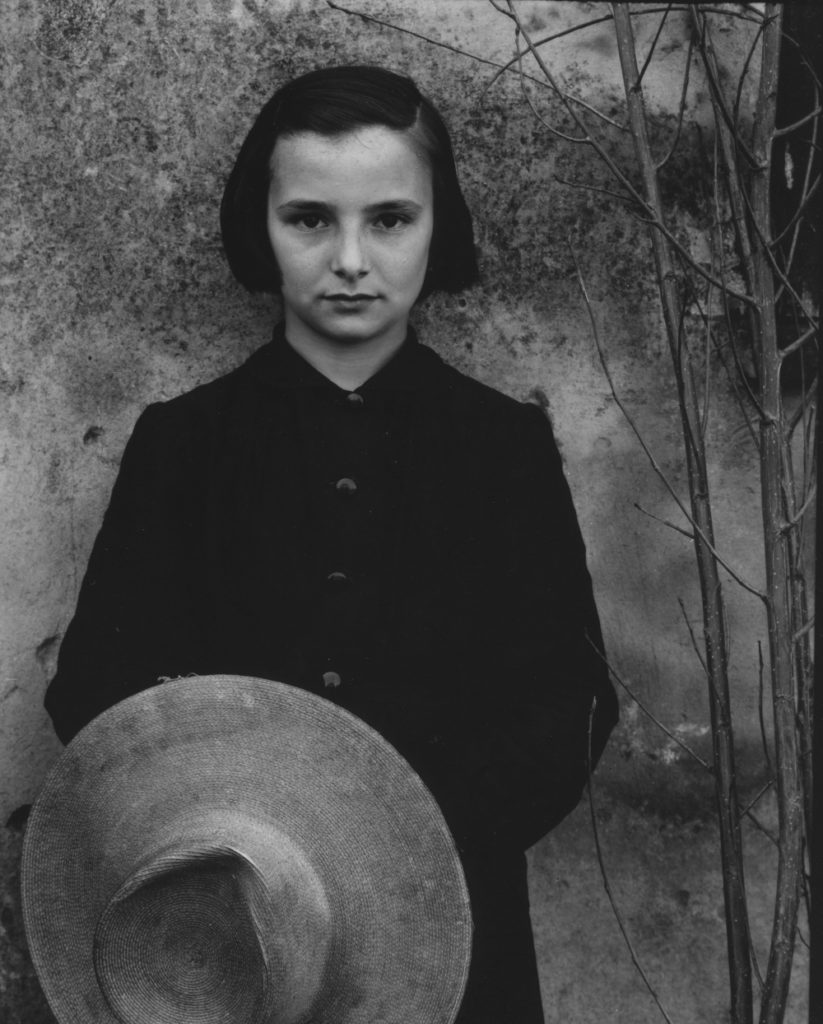

There is a conspicuous difference in the emotional content between Strand’s images of Mexican people in the film and his photographs, which are stylistically powerful but lack intimacy and warmth. This is likely due to two reasons. First, Strand was a reserved individual who did not speak Spanish and relied on interpreters to communicate with his subjects, and inevitably there were barriers. Second, he made liberal use of a prism lens, which made the person in front of the camera falsely believe that Strand was photographing someone else. This may explain why in many of his street portraits the face of the subject is turned towards one side, or, in the case of frontal shots, the subject sometimes stares at Strand with a blank expression.

There are serious ethical implications for a white man to photograph Indigenous people at close range by using a special lens to make them believe that he was shooting something else. Redes, happily, has no such issues: though somewhat doctrinaire, it is an unrivalled pinnacle of proletarian storytelling. The influential essayist George Seldes called it “one of the great achievements of the camera, superior to almost everything ever done in the United States, ranking with the ten great films of all time and all countries.” It has also been hailed as a precursor to neorealism, in particular to Luchino Visconti’s 1948 masterpiece La Terra Trema, for its use of non-actors, all location shooting, and social expression.

After working on a series of ideologically charged films, the most notable of which was Native Land (1942), Strand abandoned filmmaking. In 1950, he permanently self-exiled to France, driven to leave America by the relentless persecution of intellectuals and artists by the House Un-American Activities Committee. He turned to the production of a series of remarkable photo books that combine images with texts by different authors, most notably Time in New England, Tir a’Mhurain, La France de Profil, and Un Paese, a collaboration with Cesare Zavattini, the foremost screenwriter of Italian neorealism. In these volumes, the combination of photographs and writing sees each medium expand and resolve ambiguities of the other, creating penetrating portraits of places in time.

Eventually, Strand came to rely on a working relationship with his wife, Hazel Kingsbury, that enabled him to produce some of his finest portraits. Referring to Strand’s working procedure in Italy in the early 1950s, curator Sarah Greenough writes, “Hazel … would establish contact with the people Strand wanted to photograph, putting them at ease, while Strand was setting up his large awkward equipment. With a rapport thus established, Strand could concentrate on recording the image and expression he desired.” These portraits are among Strand’s most intimate—an achievement for which Kingsbury surely deserves some credit.

Helen Levitt

If photography can be called the mother of cinema, then cinema has surely been a grateful child. It gifted photography a singularly important technical innovation: 35mm film. In 1920, Oskar Barnack invented the Leica, the first camera that could use 35mm film. It was small, portable, and unobtrusive, and could be handheld, liberating photography from cumbersome, heavy cameras and tripods, and helping to revolutionize photojournalism.

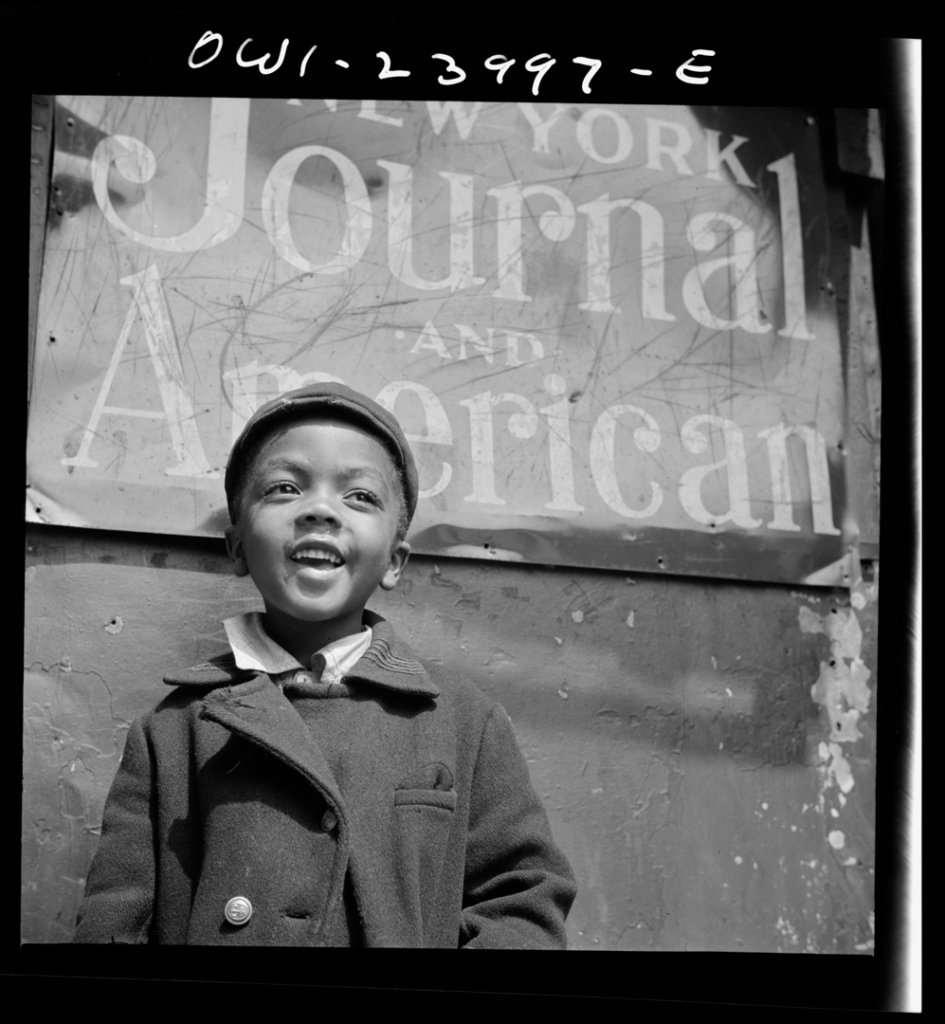

It was with the Leica that Helen Levitt (1913–2009) was able to leave a lasting legacy in photography. Levitt would emerge as a photographer of New York in 1936, two decades after Strand. Self-taught and working independently, she was inspired to use the Leica after meeting the legendary photographer/filmmaker Henri Cartier-Bresson. For her, the essence of the city was embodied in the hordes of humanity that lived there, not in the monumental skyscrapers or bridges. She photographed the in-between world of public and private space: the continuum where they merge, such as the sidewalks, front stoops, shop fronts, doorways and windows of the tenements in Spanish Harlem and the Lower East Side. This was where successive waves of European immigrants, Puerto Ricans, and African Americans made their home. Their New York was the city of the working classes and underprivileged, who lived in crowded conditions. The city of the poor went mostly unnoticed by outsiders, a far cry from the powerhouse city presented in Manhatta. Levitt saw her work as a form of political action, in the same way that Strand did. She declared in an interview on NPR: “I decided I should take pictures of working class people and contribute to the movements: […] socialism, communism, whatever was happening.”

There is an uncanny sense of candour and straightforwardness in her photographs, showing the exuberance above all of children being children, intimate and devoid of any artifice or sentimentality. It is as if she was one of them. Her pictures came to the attention of major publications like The New York Times and Fortune, and also the Museum of Modern Art, where she was given a solo exhibition in 1943. She met Walker Evans and James Agee, who both mentored her, the former photographing with her in the New York subway and the latter writing the introduction in her book, A Way of Seeing (1946).

Like Strand, Levitt soon turned to filmmaking. In 1948 she made In the Street, in collaboration with James Agee and Janice Loeb, as a silent film, which they were unable to finish until 1952. The film opens with a prologue that is as startling in originality as it is prescient of the nature of street photography, whether using a still camera or a film camera: “The streets of the poor quarters of the great cities are, above all, a theatre and a battleground. There, unaware and unnoticed, every human being is a poet, a masker, a warrior, a dancer: and in his innocent artistry he projects, against the turmoil of the street, an image of human existence.”

Filmed in cinéma vérité style, In the Street consists of some 125 shots of children and adults going about their daily lives, with no overall narrative line or plot. Levitt follows the people as they move, play, or argue among themselves, attempting to capture “an image of human existence.” The film is really an extension of her photography: it is almost like an exhibition of moving pictures that we see on a screen instead of a gallery wall. Levitt worked on films in the post-World War Two era, most notably The Quiet One (1948), a poignant drama about the rehabilitation of a troubled boy, which she co-photographed and -wrote; in the latter capacity, she was nominated for an Academy Award. She returned to photography in 1959, experimenting with colour film.

Although Levitt received two Guggenheim grants, was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, worked with seminal figures like Luis Buñuel, and was a pioneer in the use of colour photography, she has remained a “photographer’s photographer.” Clearly, Levitt suffered from gender discrimination throughout her career. Curator Walter Moser has stated: “Joel Meyerowitz, Stephen Shore and William Eggleston have always been hailed as the pioneers of fine-art color photography, but Ms. Levitt had her exhibition of colour work at the Museum of Modern Art some two years before Mr. Eggleston … Very often women photographers or women artists are overlooked, and that’s a thing that we want to correct.” Ironically, and as so happens to many artists, it was only after her death in 2009 that Levitt started a rapid ascent to international stardom.

Gordon Parks

Just as Levitt was a victim of discrimination, so too was Gordon Parks (1912–2006), an African American from rural Kansas who had to fight against racism in a segregated America. But unlike Levitt, Parks succeeded in becoming well known in his own lifetime. During his long career, Parks was a renowned photojournalist, fashion photographer, feature filmmaker, musician, composer, painter, and writer of novels, poetry, memoirs, and technical books about photography. He broke ground both as the first Black photographer to be hired by Life magazine, and the first Black film director hired by a major studio in Hollywood.

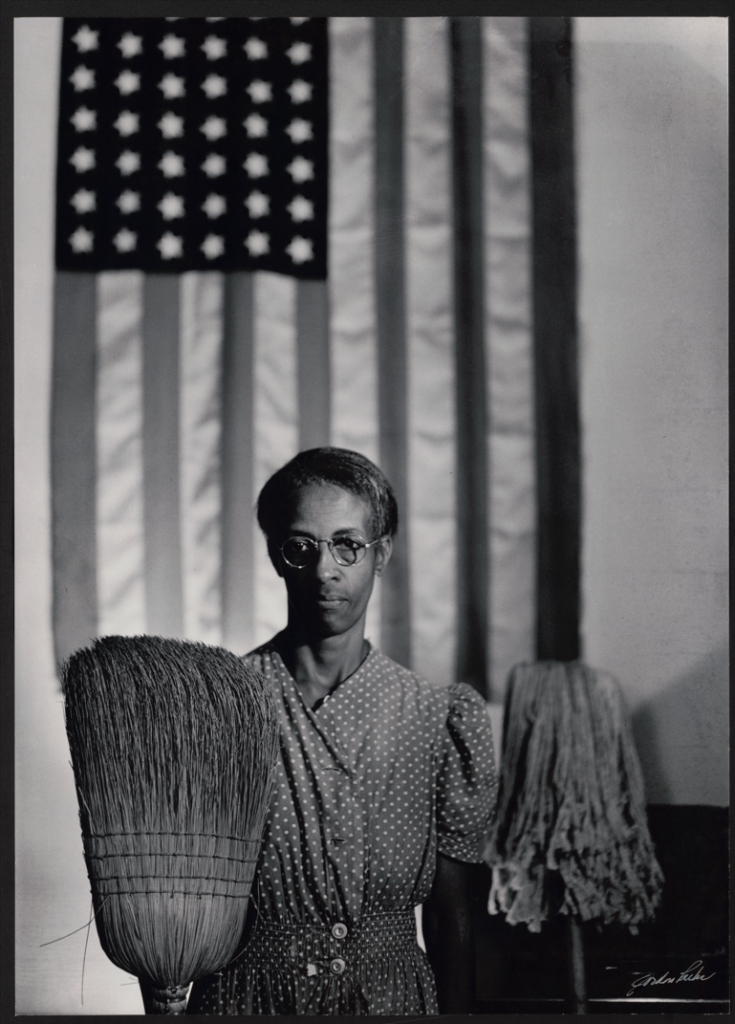

Parks made one of the most iconic photographs in history, American Gothic, at the beginning of his career in 1942. In a deliberate parody of the famous painting American Gothic by Grant Wood, Parks posed Ella Watson, a cleaning lady in the offices of the Farm Security Administration, holding a broom in one hand and a mop in the other in front of the American flag. It is a picture of provocation and affirmation, a picture of militancy. Like Strand and Levitt, Parks was very political; unlike them, he was also very pragmatic. “I choose to use my camera as a weapon against all things I dislike about America—poverty, racism, discrimination,” he declared; on the other hand, he also became known as an exquisite fashion photographer.

Working at Life magazine and producing in-depth stories, Parks gained organizational and narrative skills that would later facilitate his transition into feature filmmaking. The production of a major story at Life magazine was a long process. Stories had to be developed, researched, and planned out before the photography could begin. The phases of pre-photography for a photo essay and pre-filming for a film are not dissimilar, and a photo essay can often look like a compressed film.

To produce his first photo essay for Life about Red Jackson, a young Harlem gang leader, Parks spent a week with him driving around, gaining an understanding of the area and the trust of its characters. Only then did he start to photograph. When published, in 1948, the essay caused a sensation at Life because it revealed a powerful new talent who was able to tell important stories that were inaccessible to others—stories molded according to editors’ vision, to be sure, but which had not been told before in the pages of a major magazine.

Time and again the editors relied on Parks to photograph sensitive issues like racism and poverty. In 1961, Life sent Parks to Rio de Janeiro to photograph the abject poverty of people living in their ghettos known as favelas. He spent weeks photographing a 12-year old boy, Flávio de Silva, with his family of ten living in a dilapidated shack. The boy suffered from an acute form of asthma, which would kill him within a year unless treated. Parks produced such emotionally powerful photographs that Life’s readers responded to the article by sending money for the boy and his family, care of the magazine. Parks returned to Brazil and brought Flávio to the United States for medical treatment. He then created a 12-minute film, Flávio, which tells the story from the boy’s own point of view. Staged footage is mixed with many of the photographs that Parks had taken on assignment, using techniques like panning, zooming, blurring, and fading to enhance or extend their use as component parts of the film. Parks said he made the film “simply because when people saw the still pictures they refused to believe such conditions could exist.” But according to Ryerson Image Centre director Paul Roth, he had another compelling motivation: ambition. “He had succeeded as a photographer and wanted to become a published author, filmmaker, and composer … and he left the magazine specifically so he could ‘branch out’ and try other means of storytelling.”

But Parks had seen the writing on the wall for big picture magazines, and their impending demise. In 1972 Life shut down, but by then Parks had already become a feature film director. Between 1969 and 1976, he directed six films, in which he told stories of the resilience and dignity of African Americans. His first feature film, The Learning Tree (1969), was an adaptation of his autobiographical novel, and was filmed in his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas. The 14-year old boy who had left in poverty now returned home as a Hollywood director and a world-famous photographer. His subsequent film, Shaft (1971), was a huge hit: a thriller featuring a Black detective who is refined, kind, fearless and oh, so sexy—and who outwits the white mafia characters. Leadbelly (1976), is an historical drama about the legendary American blues singer and composer, who overcomes poverty, racism and injustice to become a folk music legend in his own lifetime, not unlike Gordon Parks.

Unlike Strand and Levitt, who in their filming kept very close to their concept of “pure” documentary photography, Parks did not. He knew that if he wanted to tell stories about Blacks to foster pride and dignity in their lives, his “weapon” would have to be the Hollywood film. He succeeded, creating commercial hits that empowered the first generation of Black film artists. “What he did was the inspiration that [I] needed,” recalls Spike Lee. Parks was not only a master storyteller, he was also a master strategist.

Conclusion

Strand, Levitt, and Parks were three artists who believed that art is inherently political because it cannot be divorced from the realities of life. They used film and photography almost interchangeably, recognizing the material and aesthetic closeness of the two media. Though they were contemporaries, they did not work together, nor cross paths. But their work is connected by the common objective that artists, in seeking self-expression, are equally bound to use their art to create awareness, fight prejudice, and be a catalyst for improving the lot of humanity.