Every junkyard, while teeming with trash, has its share of treasures. I see cultural junkyards as attractions where humans wander and sample the ornaments of creativity. In recent years, corporate streaming services have provided us with ever more junkyards, while making it difficult to find the treasures, especially if you’re looking for Canadian content and quality documentary.

Indeed, while each service abounds with drossy bulk, each also has its fantastic finds. Amazon’s Prime Video, home to a hodgepodge inventory of scrap collected without an obvious curatorial strategy aside from “we sell everything!” has its Small Axe exceptions. Disney+ has, among its endless streams of mediocre late 20th century TV and movies, its standout WandaVision (and, more recently, Reservation Dogs). Crave has more treasures thanks to the inclusion of HBO and Showtime fare, and so one may discover occasional gems like I May Destroy You. Netflix, while seemingly less judicious in its programming than HBO but more selective than Amazon Prime or Hulu, has a good deal that isn’t easily discarded to the bargain bin. That’s due in part to economies of scale: the Los Gatos company has an enormous budget and debt roll to repurpose shows through licensing, like Community or the Canadian, publicly funded Schitt’s Creek, as well as to produce its own branded, worthy programs like GLOW or Ozark or comedy specials—many by BIPOC performers—that have thankfully broken stand-up loose from its oppressive moorings.

One problem is how to find the jewels amongst so much junk in digital spaces dominated by the lowest-common-denominator landing pages and addictive-by-design series that can make you forget what you were looking for in the first place.

Netflix and Documentary: Three Hitches

The human-centered, attentive curatorial system used by the best video stores has been replaced by algorithms—the calculations of computational software designed to show us options but really narrow our field of choices. It is data processing for the arts, and there is little care to be found in the process. The listless scroll-search has been compounded by television platforms like Netflix and its inept army of likebots that algo-curate (a neologism I’m using in the sense of the Greek algos, for pain, and algorithmic programmation) the junkyard in such a way as to ensure the seekers will seek for eternity, despite the data-mining, machine-learning rhetoric.

Despite its culture-disrupter status and the company’s woke willingness to release diverse programming (queer-, BIPOC-, and neuro-diverse character-centered shows, for instance), Netflix, when it comes to documentary, maintains a relatively familiar formula. The platform has its share of top shelf docs but there’s a lot of other stuff in the way, and it’s difficult to find the gems.

Netflix has pioneered the serialization of documentary, regularly taking subjects and stretching interpretive treatment out over the mini-series format usually reserved for fiction. This is an intriguing development for non-fiction storytellers who are not only seeking the kinds of large audiences Netflix can deliver, but who can take more time to tell a story, and, as is required, procure more money to do so. Documentary used to call television home, but from the 1980s to the 2000s, that home became less and less hospitable for a range of reasons. Festivals and the internet rushed in to save the genre from its shrinking visibility, but forces of commercialization and the challenges of a crowded market mean those reception sites are limited in their rejuvenating scope. Netflix and platform television arrived at just the right time and the possibilities for a new era of documentary exhibition are seemingly limitless.

There are three central hitches, however, in betting on the platforms, and Netflix is the best example of the ways in which this approach can go askew for non-fiction screen storytelling. The first involves the company’s inhuman curatorial approach, where visibility, and therefore knowability, comes down to a single landing page screen and the data-dependency philosophy that structures the whole experience along financialization forces like investment, dataveillance, and risk management. The second is the commercial emphasis on pumped up Americana at the expense of independent, local content. The third is the narrowly manifested docuseries form, which is contingent and constitutive of the first two concerns.

Pretty, Algorithmic Docs

The archetypal Netflix docuseries follows tightly articulated conventions packaged mostly as spectacular Americana, mainly by men about men. There is a tendency to simplify narrative to the A-B-C level most children can follow, helped along by incessant plot point signposts. Style champions substance, with dramatic turns, manipulative music, smoke and mirrors, and cliff hangers, ensuring that the action never slows down, allowing for time to reflect. There is a socio-political, and narrative, propensity to symbolically focus on what’s broken and not why it’s broken or how to fix it, and a reliance on doc subjects as fiction-like characters who serve plot advancement more than deepening an understanding of the human experience. And of course, there is the sacred vow to the stretch oath: even if the story can be told in 60 minutes, it must be dragged out in a 4-6 round match, deploying unjustified repetition and yawning sequences, even tactical obscurity, to throw audiences off the trail of gratuitous screen time. This results in content unnaturally fit to form. Sex and violence provide the whole formula with a salacious bent, the promise of transgression that, combined with the other qualities above, fuels the binge (alternatively celebrity, travel and food will do the trick).

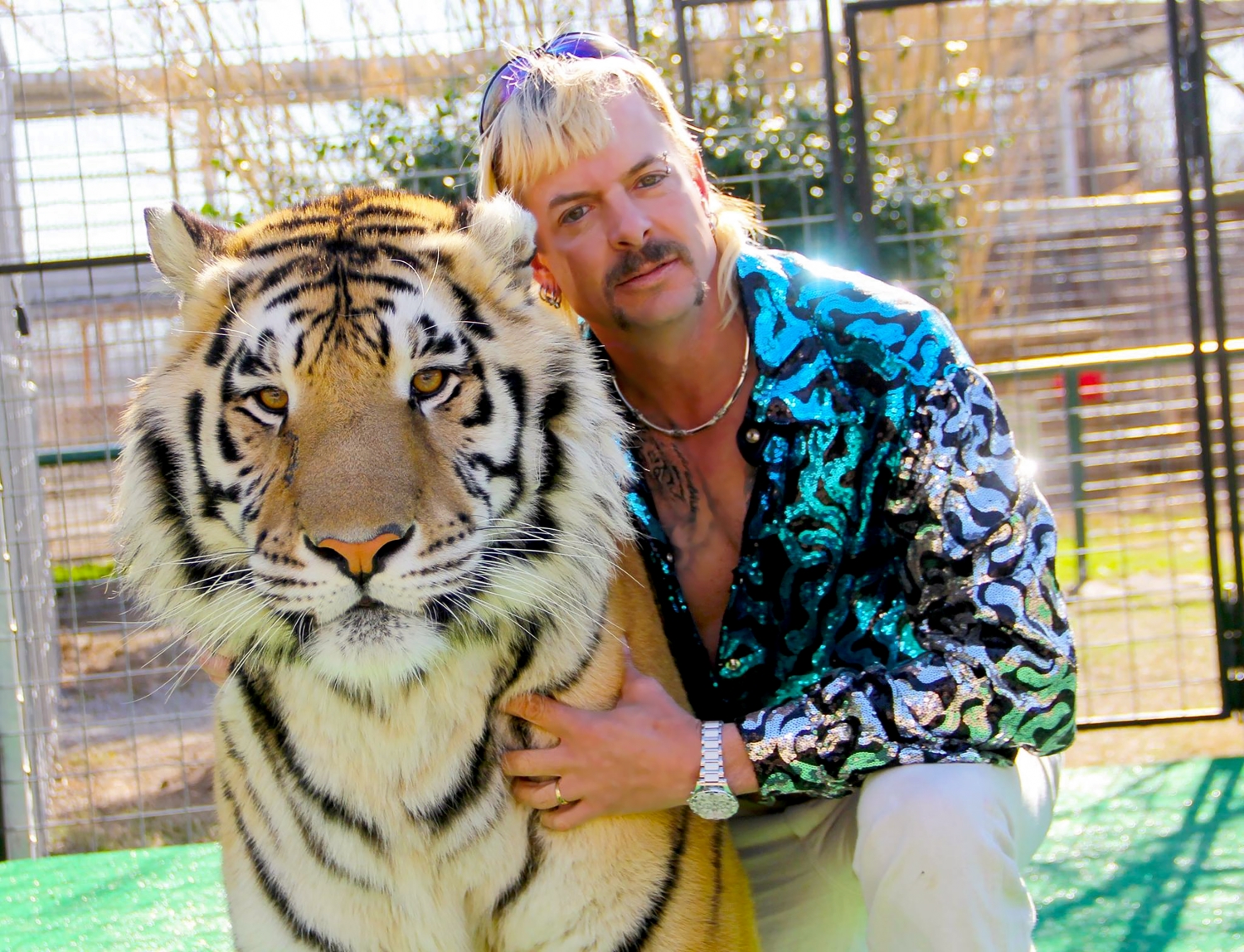

Guy Debord’s argument in Society of the Spectacle—over 50 years ago—that spectacle reduces lived experience into a series of commodified social relations, manifested as visual culture, anticipated platform capitalism and the Netflix docuseries with great prescience. The elements I describe do not define every docuseries fully and accurately, and as such I like to think of works falling into place along a kind of sundry bell curve, that can be called the Tiger King Curve. Whether one labels it train wreck television, trash TV, trauma porn, or junk TV, the docuseries is a worrying staple on the Netflix platform and, judging by its popularity, we audiences are drawn to it like vexed moths to the junkyard bonfire.

The Netflix docuseries that fall at the tail ends of the Tiger King Curve, like Song Exploder (which features celebrities), may shirk many of the aforementioned qualities that congregate at the peak of the curve (where you’ll find Joe Exotic). Netflix indeed has great feature docs like 13th, Crip Camp, and Dick Johnson Is Dead, and even some liberal activist works, that I call “pillage docs,” like The Social Dilemma, where the immoral, avaricious architects of oppressive systems are given atonement pulpits and permitted to school audiences on why the thing they built is so wrong, so problematic (thus cashing in twice—salvation pays!). Netflix’s algorithmic musculature flexes around these works, and as such they become landing page news, then trends.

Netflix’s bulwark of socially concerned docs, much like the larger mainstream commercial species they belong to and are inspired by, trade in liberal politics, simple conceits, and, at their worst, eye-glossing vapidity. In her New Yorker piece on the so-called streaming wars, Doreen St. Félix sums up the creative-critical ethos of the new platform junkyards as such: “The new shows that came into being just before the shutdown are plastic simulacra of shows of yore—the kind of pretty, algorithmic television that pleasantly empties a quarantined mind.” Like nearly everyone, I love to be entertained, and do not always care for that entertainment to be edifying or “highbrow” in nature. As a documentary fan and believer in its ability to contribute to social justice and liberation movements, though, I do worry about the tipping of the uses and gratification scale toward a pleasure of looking at the expense of knowing. We can have glossy, sensational docs coexisting with those interested in the intersection of good storytelling with socio-political animation, but when the scales tip in platform capitalism, they will favour cash and scandal over anything else.

Documentary television is being hyper-wired by Netflix, and as such trends are being set, tastes formed, cultural competencies honed and whittled into shape. The overwhelming result is pretty, algorithmic documentary television that mimics its commercial fiction counterparts, thus lacking in complexity and without a public interest agenda in sight.

Three Algo-Docuseries Hits

Three recent, popular examples serve as salient scale-tippers, from whose common wiring the Netflix formulaic circuitry emerges.

Wild Wild Country (2018) is a textbook example of a docuseries that took stretching to new heights. At nearly seven hours, the sordid tale of a cult gone wrong (do any go right?) in the Oregon desert delivered six potent hits of seamy content. At best, this debauched story could have been told in one feature length documentary. In order to stretch it out over a “season,” the creative team deployed hallmark conventions of the genre championed by Netflix: scenes are repeated, others are dragged out for no discernable effect other than to kill time, story beats are hit so repetitively that a manifest pattern (interview-archival-shocking information with dramatic music-interview) emerged by the middle of the second episode. It is expertly drawn-out storytelling that delivers the message that we humans are dreadful creatures, and I watched all 403 scandalous minutes of it.

Ramping up the depravity and predator voyeurism is Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich (2018). Clocking in at 227 minutes and told in a four-episode season, one may discover among the ruins a well-known story that runs like a gussied-up Fox News TV Special about rapist Epstein and his high-rolling, immunity-guaranteed lifestyle. While there is a smidge of institutional critique buried between disgusting and depressing personal perversion, the series offers no thoughtful analysis of rape culture, gender violence, patriarchy or capitalism. It does little in fact to advance a critical interrogation of the continued allowances afforded to powerful men to do terrible things, uninterrupted.

It wasn’t surprising, then, to learn that advertising and film production firm RadicalMedia is behind the project. This is a company that has jammed its grubby fingers into the documentary pie only very recently, producing non-fiction fare when not making hipster ads for Walmart or threatening conference organizers with legal action for using their trademarked name (the company polices use of the term it owns: “radical media”).

Lastly, the king of the docuseries jungle, the reigning champion of Netflix “true” crime, the mass-not-class train wreck television pandemic mega-hit: Tiger King (2020). When Tiger King dropped at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, I was an early addict, consuming the first seven raunchy episodes of the extended 358-minute show like a child trapped in a room with an ice cream machine (an eighth episode was later added, in a pitiable attempt to drag out the success of the series). Tiger King is a show about broken people in a broken society doing destructive things to each other (and their animal kin). It is a depressing and dreadful story of trauma, mental health and dysfunction presented in the most cheap and disrespectful fashion that while watching—eyes bugged, mouth agape—I expected laugh tracks followed by trigger warnings.

There are many ways to think about culture—as a shared and common lived experience, as systems of mediated and symbolic communication, as policy, as a commodity. The commodification of lived experience into a series of absurd, shocking, and disturbing images is a familiar trend across media. With the Tiger King docuseries, the subjects commodify, the creative team behind the docuseries commodifies, and Netflix provides the consumption platform. If you’re wondering just how commodified real life about real people can go, look no further than the world of shameless merch pimps, who, fresh from putting “Auschwitz” on miniskirts (true story), are selling “Sexy Joe Exotic Zookeeper” costumes. This is not new, of course—the commodification of culture and our willing participation in even the most debased, sordid lot predates the penny dreadfuls—yet this looks a little different, in large part because it is the slick capitalization of the contemporary documentary form, fashioned through the world of algorithmic creative management. As one friend put it—it’s Fox News dressed up like HBO and dispensed by robots.

As audiences, we are drawn to fantastic stories of transgression that are monumentally removed from our own realities. There exists a gulf between watching terrible things unfold in a fiction series like Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us and a Netflix docuseries counterpart. We should allow ourselves the expectation that the creative treatment of actuality will shine as brightly and thoughtfully in representing trauma, pain and struggle.

As audiences we share responsibility for Netflix programming, and the more we binge on dreadful docuseries, the more we feed the algo-curators the message “we want more train wreck.” Documentary is so much more than bargain entertainment. As doc fans and makers we ignore this fact at our own programming peril and watch our choices diminish as a result.

The Limits of Choice

It’s been 60 years since FCC Chairman Newton Minow called television a “vast wasteland” in a speech entitled “Television and the Public Interest.” His landmark talk, at a time when a measly three networks were airing content to American audiences, audaciously suggested a shared responsibility for the wasteland: “Television and all who participate in it are jointly accountable to the American public for respect for the special needs of children, for community responsibility, for the advancement of education and culture [and] for decency and decorum in production.”

These days there’s just too much TV for it to all be bad. I actually think we are living in one of the most exciting, innovative times of television programming and viewing practices. From the networks to the satellites to the internet-distributed platforms, there is more diversity in form and content and quality programming seen since “the telly” first usurped the bulky family radio in the 1940s. But talk of quality TV in 2021 rarely includes documentary. While excitingly new and fresh fiction shows are too numerous to count, documentaries, especially in series form and especially on Netflix, sit like cheap trinkets in TV’s junkyard.

A recent Nielsen study reported consumers could access 646,152 television shows and movies in 2020, up 10% from the year before. Combined with fiction, there exists a dizzying swirl of international and domestic TV offerings that struggle to find audiences in a heaving attention economy, even while platforms multiply. But volume does not equal quality, and choice does not track tidily on to freedom, especially with algorithms running the numbers.

Under fire for refusing to pay domestic taxes, as well as for lacklustre support for local talent, Netflix appeased the Trudeau government with a five year, 500-million-dollar investment (beginning in 2017) in platform Cancon. With annual content budgets of nearly $15 billion and a market valuation of close to a quarter of a trillion dollars, one hundred million a year for five years is a drop in the bucket for the mega-corporation that has its sights on a dominant share of the global streaming market. Schitt’s Creek aside, the Canadian section of the Netflix junkyard is a dank and dusty corner algo-curated out of view and of little concern to its corporate custodians. To be fair, the company has also forged other Canadian funding programs, mentorship initiatives and media arts collaborations. These are worthy efforts, but what are they doing for Canadian documentaries and will any Cancon be easily located among other treasures in the junkyard? Doubtful, as Colin Jon Mark Crawford reminds us in his new book on the company: “Netflix remains overwhelmingly US-centric, ever focused upon the American power centers of Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood.”

Netflix is providing a highly addictive platform in which many audiences, tastes and demands are created. As we expose the wiring that keeps the junkyard alit, a nagging question remains: How long before we notice that non-fiction stories all start to look the same?