“Anytime someone hears me say I’m from Cuba, they will come and tell me about their holidays,” director Tamara Segura says with a laugh.

Those all-inclusive resorts so many of us have relaxed in over reading week and Christmas break? “I’ve never seen them in my life!” she says.

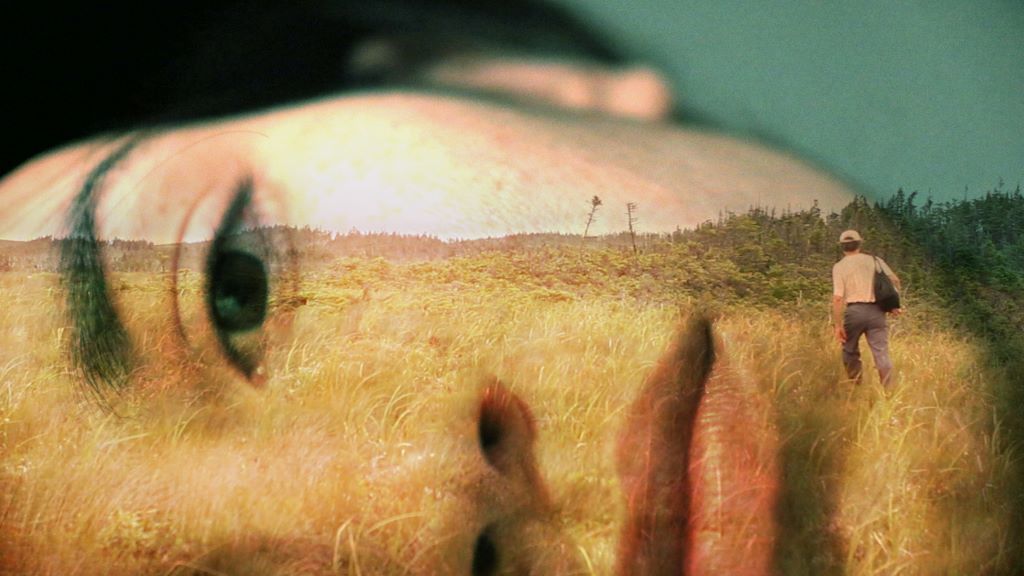

Segura’s latest film, Seguridad offers a different look into her home country beyond the poolside bars and sugar cane plantation excursions. “It was important to show a side of Cuba to Canada that’s not as common,” she says. “[The film isn’t] talking about the political, economical…none of those things are at the forefront of this story. But they’re there and they’re obvious.”

The story that Segura does unfold is a personal one. After the untimely passing of her father, she came into possession of a handful of documents and photographs that began a long and emotional exploration of understanding and in the end, forgiveness towards the man who caused her and her family so much pain. Seguridad offers a personal essay confronting universal truths through Segura and three generations of women in her family as they all attempt to reconcile the good-natured son and father with the violence and fear he brought into their home.

POV spoke to Segura over Zoom from her house in Newfoundland days before the filmmaker was scheduled to attend the Canadian premiere of Seguridad at Hot Docs 2024, discussing her and her family’s initial hesitation surrounding the film, as well as Segura’s thoughts on the ever-changing Canadian film landscape.

POV: Rachel Ho

TS: Tamara Segura

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: I think you and I come from similar backgrounds where keeping family matters private is extremely important, especially for our parents’ generation and older. Was there any resistance from your family in making this movie?

TS: Yes, it was a long process to — well, first to convince myself that it was a good idea, and then to create that trust with them to feel like we could go there together as a family. I think the only reason why we ended up doing it was because time had passed. My father’s been dead for 10 years now and I think that distance allows people to refer to the past more easily, but it was a long process to create that sense of safety for them. And me going in front of the camera, rather than behind the camera as I originally had planned, was also [part of] that.

I wanted to create that safety for all of us. Holding their hands in front of the camera and being as vulnerable as they were was very important. I didn’t want to hide behind the camera and just get them to share their deepest wounds. It felt very unfair. My way to cope with that was turning myself into an active character. I will be the one holding the story and you can participate as you wish, so they agreed to the conversations. There were topics, especially for my mom, that were hard. It was the first time we ever talked about those things.

POV: I was going to ask you whether you had discussed any of those instances beforehand or if what we saw in the film was the first time. What about with your grandmother? Was it the first time you had spoken to her about your father in that way?

TS: It was all a big first for everybody — my siblings, everybody. Of course, we’ve talked about my dad, but it’s the first time just sitting down and really going in depth into what it meant: having him in our lives, being so disruptive at times. We had never done that, and we haven’t done it afterwards, to be honest. I think we might start talking more about it after we all watch the film together, that might trigger more conversations. It was a very, very, very scary thing to do for all of us. And for me, it was terrifying because I had to be between two worlds: I have to be vulnerable and be present with them in the moment as a daughter, but also, I had to be very mindful of the practicalities of the shoot. Is that microphone working? Is that light in the right place?

POV: Did you find putting on your director’s hat helpful in stepping away and giving yourself a break, or did it just complicate things?

TS: It was more complicated, I would have loved to have been 100% present in the moment with them and share that as a family. The human aspect is infinitely more important to me. So having to direct was actually an inconvenience, because I think I could have gone deeper into many of the topics if there wasn’t a camera, if I wasn’t directing, if I had been alone in the room — we could have unpacked so much more.

POV: Were there any topics that your family decided was off-limits for camera?

TS: I don’t think so. My grandmother had a big emotional moment [that] ended up not being in the film because it was not necessarily related and it would have taken a lot to explain. But there were moments where she was really emotional. We just stopped everything and made sure that she was okay. Especially the conversation we had was really scary because she’s older and she has a heart condition. It’s so delicate talking about these things and you question, “Am I re-traumatizing them in a way?” So that [safety] was my top priority.

POV: In the film, you mention how both you and your sister ended up in artistic professions, most likely in part due to your father’s artistic abilities. When you began pursuing filmmaking, did you ever feel a weight that someone who caused so much pain in your life was also in some way responsible for this passion and outlet?

TS: At the time [when I started filmmaking], I never made the association. This came much later, when I actually discovered his photography. At the time, I couldn’t have thought of him as an artist or having an artistic vein because when I was a child and he was doing the photography, I was too small to remember those things.

While making the film, [I had] the a-ha moment like, “Maybe I’m a filmmaker because I’ve been around cameras my whole life and looked at his photos.” He definitely had a lot of curiosity and an artistic eye. Then looking at my sister and [knowing] it has to come from somewhere — neither of our mothers are artistic at all. There is nobody else in either of our families that are interested in the arts.

So it was like, “Oh my god, this all comes from my father,” and then embracing that aspect of him, being grateful, and accepting that as part of my identity. But it took me years honestly, it took me starting the documentary to put those things together.

POV: Something that’s interested me recently is re-defining what’s considered a Canadian film and I think your movie adds to that discussion. It’s not just English or French movies anymore, it’s films about the people of Canada and their ancestral lands around the world. As a newer filmmaker in the country, what’s been your experience working in Canada’s film industry?

TS: I think that Seguridad could have never existed in a place different than Canada. It’s really the only place where a story like this is possible. The culture and just the way it’s funded, especially for immigrants. I came here with no English, no French, no money, no family. It’s almost a miracle that I got to make a feature film. Also the themes [of the film] and how I managed to talk about those things, I wouldn’t have been able to do that if I hadn’t come to Canada. That’s not the culture in Cuba. Maybe I would have made a film about my father, [but] it would have been so different from the one that I ended up doing because here it’s so much easier to talk about mental health and intergenerational trauma. We have so much more awareness.

But it is still very daunting to me. I feel like I am expected to tell Cuban stories and I am expected to be the Cuban Canadian representing your community and that’s not necessarily the type of filmmaking that I’m interested in. This story is very specific, and I got to talk about Cuba — I got that off my chest. But the type of stories I like are more about human beings, relationships, families. I often find myself expected to be the Latino filmmaker and tell the Latino story. That scares me a bit. I don’t know if I can be that or if I want to be that.