[Publisher’s note: This article originally appeared in POV issue #119 (Fall 2023), published in print in September 2023. For complete and immediate access to articles in the print magazine, please consider subscribing.]

Origins: An Independent Point of View

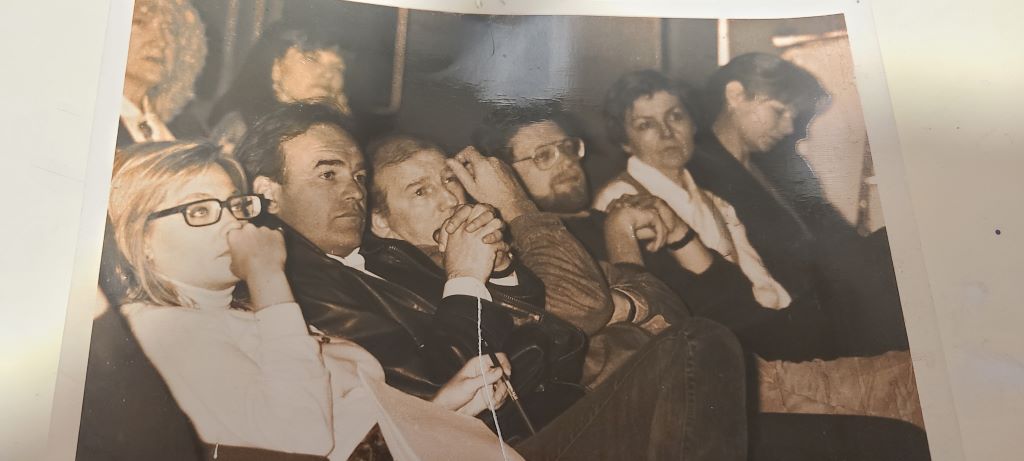

In July of 1993, a small-but-feisty group of filmmakers gathered in a Toronto apartment to talk about the state of documentary making and sharing in Canada. Aware of the uneasy relationship between documentary and the commercial film industry, and the related struggle to fund independent, POV productions, the clutch of film folk, who were also members of the doc advocacy group the Canadian Independent Film Caucus established a decade earlier, discussed the challenges facing independently minded documentarians. Their edited meeting notes would subsequently appear as descriptive write-ups for the very first Hot Docs edition’s industry workshops: “What are the dangers of losing editorial control? How can independent producers work out questions of editorial and creative control with broadcasters? What criteria should funding agencies use to evaluate and prioritize their investment decisions?”

These questions suggest that Hot Docs began on a critical and mobilizing note, addressing concerns of advocacy, authorship, and agency. Debbie Nightingale, who joined Hot Docs as the festival’s first manager, insists that the first edition of the festival was the “purest” because it was a “documentary festival for, by, and about documentary filmmakers.”

Hot Docs’ key innovator and first chair Paul Jay remembers it as a “place for independent POV documentaries” and a social space for the community to gather around those works. These aspirations appeared at a time when television’s death grip on documentary (often manifesting as hosted “informational” programming) was loosening ever so slightly, while also, after a decade of corporate confluence and disastrous conservative policies, the late ’80s saw a few doc hits illuminate the cinema.

The CIFC Years (1993–1999)

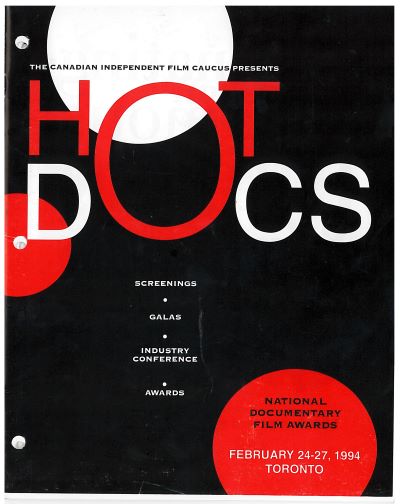

With $10,000 procured from Kodak for a festival feasibility study, Jay, Nightingale, Barri Cohen, and the rest of the founding members planned a winter 1994 launch of the first edition of what would become the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival. Initially operating under the awkward moniker Hot Docs! National Documentary Awards 1994 and spanning four days in February, the inaugural event was made up of four components, which are displayed on the edition’s original program cover: “screenings,” “galas,” “industry conference,” and “awards.” Encounters at the first edition were intimate, earnest, and self-reflexive in nature.

The initial years emphasized artistic and professional exchange between practitioners and industry folks through workshops and screenings that were mostly in non-cinema screening locations such as hotels and nearby coffee shops. The diversity and unconventional nature of the venues speaks to the festival’s grassroots/DIY nature as well as a taking-it-to-the-community ethos.

Hot Docs organizers had a tacit economic agenda geared toward the twin goals of supporting and expanding the activities of local documentary advocacy, conducted under the auspices of the CIFC, while promoting the production, circulation, and visibility of independent documentary outside of conventional forms and platforms. Barri Cohen recalls their emphasis on Canadian content: “The initial mandate was to primarily showcase Canadian work, that is to say the priority was Canadian work, with an international stream.”

Establishing a local, alternative cultural space parallel, yet still linked to, mainstream and commercial media operations at the time, the first Hot Docs editions were almost entirely bereft of American productions—Hot Docs’ first edition screened 18 films, all Canadian. It wasn’t until the third edition, in 1996, that a small crack appeared in the Canadian granite, when out of 52 programmed films, one American and three European films were included in the lineup. In 1999, the last year CIFC controlled the festival, 49 of 62 films screened were Canadian and six were American. This period of programming reflects the initial mandate to showcase independent and POV Canadian documentary, and can be positioned within the social, political, economic, and historical context of the (continued) US domination of Canada’s film exhibition market. The conflation of commercialism with American domination can indubitably be read as a symptom of a nagging cultural nationalism, yet conjuring the double threat can also be seen as following from a critical analysis of the Canadian film market’s unique position, where there is at once a relatively (to the US especially) robust history of state- and alternatively funded “social interest” documentary production, combined paradoxically with anemic distribution/promotion/ exhibition opportunity and free-market proximity to the most powerful movie industry in the world.

No surprise, then, that the 1996 Hot Docs winner for best arts/culture/ biography documentary by a broadcaster was the provocatively titled CBC doc The Americanization of Canada: How We Lost It at the Movies, produced by Jill Offman. Importantly, there was no section partitioned off for Canadian content in the early Hot Docs programs, which were de facto Canadian programs, thus manifesting the festival’s mandate to respond to and promote “local” culture. Despite this mandate, the period, like, to a lesser extent, those that followed, reflected the dominant settler culture of Canada in that Indigenous voices—on screen, beside it, and behind it—were, for the most part, criminally absent.

Despite its colonial and other representational shortcomings, Hot Docs began as an alternative to the status quo. With the inclusion of cultural, political, social, and experimental categories, the early Hot Docs editions beckoned toward a more diverse doc terrain, moving beyond the stagnation of talking-head TV. The festival was, however, balancing indie, local, and diversity values without decoupling from the wider industry, as evidenced by two 1995 initiatives: a section on “international films for Canadian audiences” and “The Industry Centre,” which later morphed into the Toronto Documentary Market (now the Hot Docs Forum). These developments point to the complexity of a project that, on the one hand, passionately pursued an independent film focus while, on the other, recognized the need to be open to new industry funding and presentation windows.

The introductory comments in the 1997 program from Paul Jay and Joanne Smale acknowledge the festival’s shifting role in providing a platform and space for the international mingling of culture, especially between Canada and Europe. They express pride at being “the documentary bridge joining European and North American filmmakers and broadcasters,” pointing to the increasing social significance of a media arts institution brokering between the local with the global. The 1997 program also mentions Hot Docs as a prime destination for “schmoozing” and doing business. This suggests strains were developing at the festival, as it endeavoured to develop its industry/commerce side while attempting to hold on to its roots as a community-oriented, artist-created project with international ambitions. This tension between international commercial imperatives and local community concerns would eventually metamorphose into the festival’s current disposition, where the former has, over time, overpowered the latter.

By 1998, CIFC’s final year in control, Hot Docs had grown in size (from 500 to 5,000 attendees), stature (from 100 submissions to 390), budget (the 1994 edition’s was $100,000; by 1998 it had more than tripled), and scope, while managing a shift of identity and values borne of the contradictions such growth brings.

New Management (1999–2019)

It was in the same year, 1998, that the CIFC members concluded that a conflict of interest had developed between showcasing their members’ documentaries at Hot Docs and the advocacy efforts of the organization. Facilitating meetings between government commissioners, funders, and filmmakers one day and lobbying the same government the next proved fraught and unsustainable. The festival was thus separately incorporated as a non-profit and charity in order to clearly separate the promoting/showcasing work from the lobbying. CIFC would continue to benefit and build on the efforts of the first five years by maintaining half the seats on the Hot Docs’ board of directors and collecting a percentage of festival revenue. As CIFC members transitioned out of organizing the festival and new management members came into the fold, a transformation from an artist-run, community-led festival to a management-run, professionally helmed one began, reflecting a larger shift in the festival world.

In 1999, Hot Docs moved from winter to spring and relocated to cafés in Little Italy, which management described as “opening up the festival to the public.” Doc outsider Chris McDonald was hired as festival CEO (later changed to executive director). The festival team embraced the audience-expanding direction of the festival, now under McDonald’s guidance, as reflected in the 1999 program: “This year, we welcome a wider public audience to more gala events and café screenings, all with increased opportunities to hear filmmakers introduce and discuss their work.” This diverse exhibition and reception terrain—from the hotel industry rooms of earlier editions to urban neighbourhood cafés, with gala events and screenings held in local cinemas like The Royal, the Carlton, and Uptown Theatre—gestures to the festival’s early exploration of place and identity as both a DIY/grassroots event and a serious advocacy institution interested in staging “galas,” a term from which notions of elegance and formality flow like glitter at a ball.

A shift in programming gradually came into effect in the 2000s, culminating in the appointment of a director of programming in 2006 and a final break with programming by committee. Between 1999 and 2019, Hot Docs screened 1,920 films, 594 of which were Canadian and 421 American, demonstrating a shift in programming that increased the presentation of work produced outside of Canada, especially from the country’s “special neighbour” to the south. More troubling was the festival’s lack of engagement in the politics of the period. In 1999, when a wave of unprecedented anti-corporate-globalization protests erupted across the planet, Hot Docs’ inaugural opening-night screening was Video Fool for Love by Robert Gibson, a purportedly “candid” and “in-your-face” Australian documentary about a “man struggling with his age… and his virility.” Hot Docs’ new managerial approach marked the year the festival initiated an opening-night screening policy that would do anything but reflect or build on the global vitality and political urgency outside the festival’s walls, although opening-night selections in recent years have reflected efforts toward Indigenous filmmaker inclusion and gender parity.

The beginning of the new management period was marked by the tagline “Entertain Reality,” a pronounced depreciation of documentary’s serious stock in actuality. The concerning coupling suggests a foreshadowing of changes in the festival’s direction in later years, when the sticky relationship between capital attractions and the culture of the everyday would be described by McDonald in 2011 as “complementary,” an astute observation that has proven prophetic. Hot Docs’ then president explained: “You have to stick at the business side to achieve balance [with the cultural side].” McDonald made these comments the year the festival opened with the hatchet job POM Wonderful Presents: The Greatest Movie Ever Sold, a cheap Morgan Spurlock brand vehicle that “ironically” champions a corporate saviour narrative for culture. The commercial imperative has since burgeoned: Docs must be entertaining first, socially engaged second—a convention championed south of the border and steadfastly gaining traction at film festivals everywhere, its propagation serving to normalize the unremitting commercialization of documentary.

Hot Docs has put considerable energy and resources into building its infrastructure, expanding audiences, and supporting industry since 1993. While new funds and training programs for documentary makers are commendable and always needed, the festival has followed an established commercial model, chartered by our American cousins at “indie” festivals like Sundance. Hot Docs likely recognizes that focusing on commercial development is key to gaining clout in the industry, as festivals are increasingly funders and producers of films, not merely showcase platforms. The festival’s history shows that considerable energy has been devoted to this side of things, but less investment has been made toward nurturing documentary’s political side. Most glaringly, Hot Docs overlaps with International Workers Day, but the festival has no connection to the demonstrations or other activities surrounding it.

Regarding festival launches: In 2003, Hot Docs opened with two personal films about American family life (My Flesh and Blood and I Used to be a Filmmaker), while a mere two months before, 16 million people protested the US invasion of Iraq. In 2008–2009, when banks were bailed out to the tune of $700 billion in the US and $114 billion in Canada, Hot Docs opened with rock doc Anvil: The Story of Anvil. In 2010, during the lead up to the massive protests in Toronto against the neoliberal agenda of the G20 Summit, Hot Docs opened with Babies, a film about…babies. In 2013, four months after Jessica Godon, Sylvia McAdam, Sheelah McLean, and Nina Wilson ignited Idle No More, Hot Docs opened with a film about a strip bar in Ontario called The Manor. Openings set the tone and tenor for festival events, and while there are plenty of political films to be found in Hot Docs’ programs, I’m arguing that openers during this period show the festival’s privileging of the business/commercial aspects of documentary over its political side. Perhaps you can’t have both: McDonald once told me that the festival “doesn’t do politics.” Yet, when cultural institutions shy away from political engagement in favour of commercial viability, we end up with ethically bankrupt entities like banks sponsoring doc festivals and other “outspoken” cultural events.

Recalibration and expansion continued throughout the new management era. Most significantly, the Bloor Cinema was purchased with a $4-million “donation” from the Rogers Foundation in 2016. Now called the Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema, the purchase of Toronto’s largest stand-alone cinema allowed Hot Docs to become a “master of its own domain” as one journalist noted.

During McDonald’s reign, the festival outgrew its DIY Canadian roots and is now one of the largest and most successful international documentary showcase events in the world. Shifting its curatorial focus away from local issues and Canadian productions, it “went global” with regard to its programming, its architecture of social relations, and the framework of the institution itself. Second in size only to Amsterdam’s IDFA and listed on most industry top-10 lists for documentary events and markets, Hot Docs is now a celebrated, permanent fixture in Canada’s documentary industry, culture, and community. During this period, it thrived by building on the initial experience of the filmmakers who created the festival while developing its own discerning curatorial tradition, one that includes a canon of entertaining opening films, exemplary selections drawn from other festivals and beyond, spotlights, awards, and—yes—galas.

Reflection and Transition (2019–2023)

In 2019, Cree filmmaker Tasha Hubbard became the first Indigenous director to open the festival. Her devastating critique of Canada’s (in)justice system brought a tough, difficult, and uncomfortable truth to the opening-night audience. nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up is certainly not a “feel-good” movie or soft on politics in any sense of these phrases, and thus I consider 2019 to be a reflective break from the new management period. Filmmakers had urged the institution to become more aware of and engage with Indigenous efforts to self-represent and to claim meaningful space in the industry. Hot Docs followed through and made the long-overdue selection of an exemplary Indigenous-made and Indigenous-focused documentary to open the festival. Hubbard, along with members of the Boushie family (featured in the film), asserted an Indigenous presence in a predominantly settler space. It was a rare, promising moment when Hot Docs used its powerful platform to truly centre voices systemically excluded.

During the fraught pandemic years, Hot Docs moved to online screenings, which continued in a reduced manner in 2023. The festival also took the laudable step of sharing online-screening revenues with filmmakers, a practice that is rare in the commercial festival world. Whether this move will manifest as policy is yet to be seen, not least of all because Hot Docs doesn’t make its policies public.

Organizationally, Hot Docs is in a transition period. Long-time administrator Brett Hendrie departed in 2020, followed this year by director of programming Shane Smith and president Chris McDonald. Marie Nelson has recently been hired as the new president. While Hot Docs’s future is uncertain, it has 30 dynamic years behind it—a prodigious history not without its share of shortcomings. It’s a sturdy base on which to stage a better, improved, outstanding, and outspoken festival, to be sure.

This article is based on a chapter from Ezra Winton’s forever-forthcoming book on Hot Docs.