Mohamed Jabaly is an award winning filmmaker born in Gaza who has been living in northern Norway for the last decade. Originally invited on a cultural exchange to Tromsø, the sister city of his birthplace, he found himself working within the film community, learning skills to help him tell the stories of his people on the global stage. His award-winning 2016 doc Ambulance provided a window into the struggles of his community, and illustrated stories that went beyond the simple headlines and hashtags that often denote what’s occurring within this troubled region. He followed that with My Gaza Online (2022), a short film about following the news from home from afar.

His feature film Life Is Beautiful, playing as part of Hot Docs’ World Showcase, documents his intensely personal yet profoundly universal struggle with an uninterested system that puts up barriers to his ability to tell his stories. With a border closed back home, and a Norwegian system demanding that he leave, we see the struggles of trying to find a home away from home, the community that embraces his struggles, and the means by which the story of his own immigration struggles mirror metaphorically the continued challenges of his legally stateless home town.

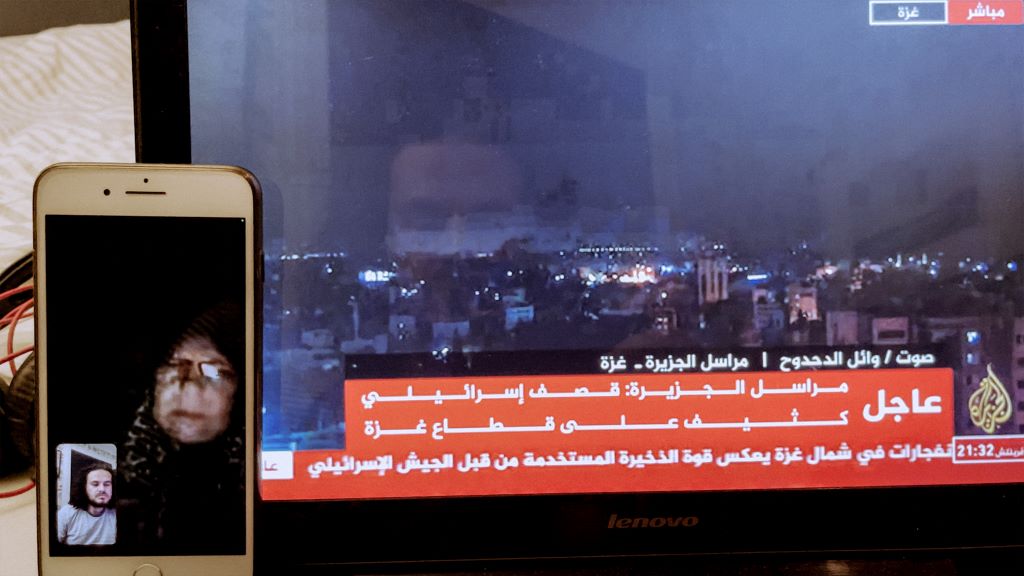

Jabaly completed Life Is Beautiful before the most recent hostilities, making the film feel all the more relevant by documenting communities that have been ravaged by conflict, with many of the buildings and communities shown now erased from existence. If the events of the world can dramatically change the way we respond to a film, this surely is a case where the recent past is seen through a dramatically different lens after what has subsequently transpired, not only for the film’s subject, but for the place he has spent the last decade documenting. We spoke over zoom prior to the film’s premiere at Hot Docs.

POV: Jason Gorber

MJ: Mohamed Jabaly

The following had been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: First of all, how are you doing?

MJ: That’s really not an easy question to answer. Usually, I would really be happy to say I’m good, I’m fine. But I start to think about the bad circumstances and the difficulties that my people and my family are living through, and I’m not so good. But I really wish to be good!

We’ve already lost so many people, lost so many close friends, and our city is not the same. Our memory has been kind of demolished as well. Of course, our memories stay in our brains. But I’m reflecting on the fact that the streets that I grew up on, or my grandfather’s house that we grew up in, are not there anymore. These are tough challenges, yet in the middle of all of this, we have to maintain our creativity, and to be mobilized to talk and reflect. I carry all of this with me when I say I’m fine. It’s requires a more philosophical answer, but it has to be this way. I hope that, at some point, we’re all going to be good and we’ll return to our normal, because our present has already been demolished this war.

POV: Then does the sentiment of the title still hold for you? Is life still beautiful?

MJ: The question of life being beautiful speaks to what I want to see. This is a future not necessarily today or tomorrow, maybe in a month or a week. This still goes to the motto of “life is beautiful” that I carried with me all the time, even while growing up in Gaza. It’s a motive for being hopeful and trying to mobilize our life’s struggle.

POV: Can you talk about how this project solidified? How did you know this was the story you were going to tell in your film, taking the form that you were going to tell your own journey with this project?

MJ: When you start to film something, you don’t know where you will end, as that’s the nature of documentary rather than fiction. Basically, reality writes the story. It’s not until the end that you sit and work with the material and make it into a shape that reflects reality. It wasn’t easy to reflect or record all of these diaries. But there’s a moment when a filmmaker decides to flip the camera towards himself that you soon realize that you are the center of a story. From that moment, the filming became more casual.

When I got the first rejection of my Visa, that was a major turning point. Another was in the courtroom – I was telling the judge that while I’m recording these moments, at some point I’m going to tell a story, whatever the result of the case was.

POV: A bit of a spoiler, but you got a student visa. Are you now done film school?

MJ: I finished that film school.

POV: Part of what you argue to stay in Norway was you didn’t need to go to film school to be considered a filmmaker. Now that you have graduated, do you still think you don’t need to go film school to be a film maker? If not, why go to film school?

MJ: [Laughs.] That’s the clash. As soon as I was back, I wanted to get all of the degrees. I’m doing a Master’s now in Fine Arts in the National Academy of Arts in Oslo, so I’m living between Oslo and Tromsø. My education has become a revenge! But at the same time, it’s not easy because it was really difficult for me to accept myself as a student. I’m sitting in the class listening, knowing I’m a step ahead of everybody. But that’s the moment when If made myself adapt to learn more, also to observe others. We are all open to learning more, there’s nothing wrong with that; it’s just the strange fact that everybody in the class is waiting to achieve what you achieved already have.

POV: When you are in Tromsø, or anywhere else outside of your home region, we see you become an ambassador of sorts, with people expecting you to speak to an extremely complicated situation and to be their personal expert. How you have reacted to how your film is being seen by others?

MJ: It’s strange. Like you said, I often answer questions in ways I never would when I was in Palestine. When I’m in Gaza, in my city, nobody questions who I am, or my identity. Everybody knows everybody. To be honest, I was wanting this film to become an answer for all of those questions.

When I’m out at a restaurant the waiter asks, “Where are you from?” Or, “What’s your name?” Once I say “Palestine” and then “Gaza,” it carries so much weight. It’s like an endless conversation. That’s the way of my life outside my home.

Of course, I will always stand for my city and my people, and hope to represent them by standing up for our rights and struggle. At the same time, I would love to be a normal person, a simple person who just wants to brag about my art and other things like that. This is a choice also I made from the beginning. When I was invited to Norway, I was asked to go on tour to show things about my culture, my city, my country. It wasn’t a vacation from day one when I was in Tromsø.

Many Palestinians do other jobs that they not require standing in front of people and answering questions. It’s not an easy choice, but I’m living with it. I’m trying to adapt to the circumstances and, of course, I want to answer as much as I’m able to answer in the way that I see what is right and what is wrong. I see now some are trying to erase our present, and that’s the moment when we have to stand and insist on our existence.

POV: It would be very simple to see this recent escalation of hostilities as taking sides without nuance, as merely good guys or bad guys, depending on your politics. How do you respond to those that wish to engage in the complexities of that situation and push back somewhat on what is taking place there and try to contextualize it in the larger circumstance to recognize what initiated this particular wave of violence? You were born, as you said, in the first Intifada, and that struggle, and its reaction, didn’t come from nowhere or in a vacuum.

MJ: No, it’s loaded.

POV: Right. But this is it. That it would be very easy for people to see your film and think that you and your experience is the entire experience of Gaza, just like people will watch the news and think they see people committing terrible things and think that is all of Gaza.

MJ: Of course, it’s easy to be put into one category and then ignore the other.

POV: How do you not ignore the other?

MJ: I try to meet them and talk to them. The whole film, on a metaphorical level, it’s exactly what’s happening in Gaza, but with different circumstances. We see someone stuck, if you imagine Tromsø as a city like Gaza, with a blockade or restriction that prevents travel. You see the people as the world that wanted to help you but can’t because the world is against you and they’re trying to make you.

POV: It’s a wall.

MJ: Exactly. I mean, the film is a letter to my mom, but it is also a letter for Gaza. At the same time, if you see it clear-eyed, or as black and white, bad and good situation, there is a country that has been occupied for 76 years. The source of the problem is the occupation. They were trying at first to make peace and it didn’t succeed. It didn’t succeed because there is one part that doesn’t want to have peace in the area. And that’s clear. That’s what you see.

You look at the West Bank and you see more and more lands being taken every day with the growing of the settlements. This should be free territory for Palestine according to the peace agreement. You look to the West Bank and you see the Apartheid system, you see the wall. I’ve never been able to go to the West Bank, and that tells you a lot! Here I am, a guy of 33 years, never been to the other side of Palestine. How is this possible?

I feel the world never got our full story. People just see fragments of our reality and truth is a kind of a casualty. Of course, people want to talk about it, but they have been talking about it for 76 years. If the world wanted to solve it, they could have. It would have been solved in ’56, for example, when they tried to put the peacekeeping mission in Gaza, or after the ’67 war, when all of Palestine was occupied.

POV: And yet, on your way back home, you were detained in an Egyptian prison trying to cross at a place controlled by them, not Israel. You were born to this, and so you understand the deep complexity of the issues, which takes nothing away from simple facts of suffering. Have you found yourself in the position of people appreciating the film, responding to the film, going to you and responding, but doing so in a way which simplifies what you’ve actually gone through?

MJ: People are receiving the film really well, I would say. People have been very moved after the film, and they are full of emotion. I will tell you an example that happened to me in Belgium, in Louwen, where a guy came to me. He’s in his 60s, I would say. He said to me he I felt my story has done something that had never happened in the 40 years that he worked within this system. He said he felt like he wasn’t awake until now, and that I managed to change his attitude.

I want to bring people closer to my reality. That’s why I decided to put the camera inside my room, to show you how it is to be this person who comes from this beautiful city that has been ruined over the years. I’m very happy to show another part or a perspective that people weren’t aware of. When I did Ambulance, I could have chosen to show more blood, but I didn’t because I didn’t want people to leave the cinema or to stop watching the film. How much is too much to show? Every single frame, even from the footage that I didn’t use in the film itself, carries a story. It may be a painful story, a detail of life, like when you see a building collapse, just for a second. It becomes normal right after this second. When we look back, we see all of the details, with each building housing a family, each with their own stories, their memories. Maybe this person saved [money] all of his or her life and worked to make a safe home for him or herself or for a family, and then suddenly it’s taken in a second.

This is something that hopefully I’m going to touch in my other works. Suddenly, when someone takes a home from you by force, then it’s a question of what comes after. What is the meaning “after”? How will these people feel?

POV: Again, those buildings being destroyed are not being done so in a vacuum. One may say that they are done out of anger, they are done out of injustice, out of revenge, or out of strategic necessity. At the same time, there are families you describe, there are members of the community that you come from, that have an ideology that you seemingly do not ascribe to. Have you been often put in a position of having to defend the worst parts of Gaza to those that have come to you?

MJ: We all seek freedom in a different way. For example, I chose a way through my way of sharing my knowledge about my city. Let’s imagine the future after the events of today. There’s a little child that has been growing up in tough circumstances, that hasn’t seen the world yet. His family has been taken from him by power, his family has been killed. His house, his school, his city, everything that’s surrounding him has been taken by a war machine. Then, when you imagine this little child grows up, years later, what do you expect this little child will be? He has no father, no mother. He knows the source that took his father and mother from him and his brother and sister, and his home and his street and his school. What do you imagine his thoughts are at that moment?

Maybe he will become an engineer. Maybe he would be an artist. Maybe he would be a musician. And it could be that he becomes something else. Because he would carry a sort of hatred or revenge, it’s not his fault that he became what he became.

POV: But then how do you break the cycle?

MJ: You break it with your own way. I had two love birds in our house. I put them in a cage when I was 10 years old in our neighbourhood, a neighbourhood which is now destroyed. But back then, one of these two birds managed to break one of the bars and escape. I tried to look for him and I couldn’t find him. But the other bird stayed inside. So that’s an example of what happened and what will happen. As long as we can’t de-weaponize the environment, as long as we put this hatred, there will be people to use it.

POV: Do you have hope?

MJ: Hope has become a heavy word for me these days. I always say I hope. But for me, the last six months, the meaning of it has changed. But I will never give up on this word.

POV: The movie was locked before the current escalation, I presume.

MJ: I didn’t even want to mention the day, but my first test screening was on the seventh of October. By then, all of the decisions had already been made.

POV: How has watching the film changed for you yourself since those events? How have you changed since you made the film?

MJ: I think the film speaks relevantly to what’s happening today, because nothing that’s happening now began only six months ago. We’ve lived all our whole lives under this circumstance. You will see the events that are in the film, and if you are blind to the situation occurring right now, you will imagine it’s exactly what is happening inside Gaza today. As to how I’ve changed? Aboud, one of my closest friends, who shot the last scene of the film, was killed three weeks ago while he was waiting for food aid. I have lost so many close friends, and I still can’t believe that Aboud doesn’t exist. He left four children and his wife alone. He was a cinematographer, a filmmaker. And yet he was not carrying his camera. He was simply waiting for the food aid to arrive so he could take something back to his family.

POV: That leaves you with sadness, but does it also, because you’re distanced from it, because you’re safe, does it leave you, unfortunately, with a sense of guilt?

MJ: Yes, and it makes you even more committed to doing something. I will do everything to keep up. Aboud and I filmed Gaza in 2021, the details of life and so on. When we were on the ground and we were filming, he was always asking why do you we need all of these details? I questioned it myself as well: “Why am I recording everything?” I didn’t know then that it would become a testimony. I didn’t know these streets wouldn’t exist anymore. I didn’t know these churches or this mosque would be destroyed. If I knew, I would have filmed more. I would have really forced myself to get out of this zone and filmed even more. But it’s become now the reality that we are witnessing today. We will rebuild and we will do everything we can to make our life better and stand, always stand for our right to exist.