Adam Curtis is a polarising and enigmatic figure. A self-described journalist and historian, Curtis has spent decades at the BBC creating sprawling, authorial film essays, connecting the dots of 20th-century history to reveal a disturbing picture of the contemporary world. Curtis is maligned by those who view him as a conspiracy theorist, propagandist, emotional manipulator, or even a crypto-fascist. But his many devotees can be found across the political spectrum. Even Kanye West loves him—whatever that means.

Much is made of Curtis’s style, which is an idiosyncratically journalistic one with aesthetic sensibilities more familiar to art filmmaking than what gets filed under “factual television.” His films are ridden with alienation devices designed to remind the viewer that what they are watching is a narrative construction, and not a neutral account of facts: non-standard use of emotionally evocative music (with a preference for Brian Eno, Nine Inch Nails, and, more recently, Burial), loosely contextualized archival footage, jarring cuts. They’re more reminiscent of Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma than anything else you’d see on the BBC, but not anywhere near as opaque and maddening as that comparison suggests. His stylistic choices reflect his idea of journalism itself as an inherently rhetorical, narrative form, and they encourage us to question his conclusions and not to be duped by his seductive ways. Leaving aesthetics aside, which is only part of what makes Curtis’s films so interesting, let’s focus on what he has to tell us about politics.

Ideas, not people, are the protagonists of Curtis’s films, and they are the motors of history in his telling of it. Ideas are bigger than people. Although people invent them and make use of them, ideas have a force of their own, which no human is able to control. The most significant ones get built out into all-encompassing systems—ideologies—which are even more powerful. And ideologies, like paranoid conspiracy theories, can profoundly influence how we interpret reality and respond to events. Curtis makes a compelling case that the history of the 20th century is best understood as a complex ideological struggle: a war for control over reality, in which ideas are both weapons employed by competing factions, and a kind of independent force of nature. For him, politics is the arena in which competing interests struggle for control over the minds of people, using ideas and ideology as the means.

In 2004, during the Iraq War, Curtis released a three-part series called The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear. Its protagonists are neoconservatism, the ideology used by the Bush administration to rationalize the War on Terror, and radical Islam, the shadowy force that emerged as the new enemy of the West in the post-Cold War era. Curtis sees these ideologies as responses to a corrosive, nihilistic liberal individualism, and the two employed similar strategies to oppose it. Both used powerful myths to counter the force of individualism: the moral duty and destiny of the United States to spread freedom and democracy for the neoconservatives, and a fundamentalist, backward-looking rejection of modernity for the Islamists. And both depended on the idea of an external, evil enemy in order to join people together in a shared struggle. For the neocons, it was forces both abroad and at home that were hostile to democracy and freedom, whether communist or Islamist, while for the Islamists, it was jahiliyyah, the state of barbarous ignorance that characterized secular modernity.

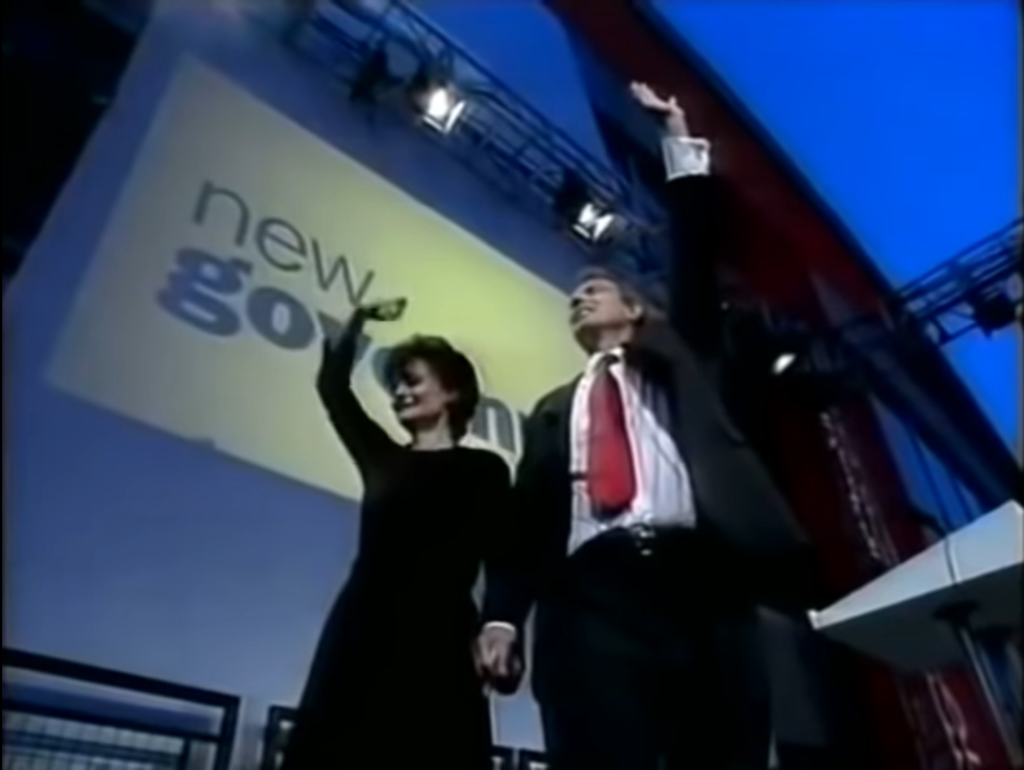

Curtis depicts the neocons as classic paranoiacs. Both during the Cold War and the War on Terror, neoconservative politicians and advisors started with the assumption that the United States was in grave danger of attack, and then consistently interpreted the facts in a way that would fit that terrifying thought. They did so because they were seeking justification for military interventions that would set America on the path to fulfilling what they deemed to be its destiny. What proved controversial was Curtis’s assertion that the enemy presented to the public to justify the War on Terror—the organized, international terrorist network known as Al-Qaeda—was a fiction created to serve the neoconservative agenda. That fear of the terrorist threat, according to Curtis, was cynically employed by politicians like Tony Blair and George W. Bush, who were not neoconservatives themselves, but who had run out of ideas that would inspire people.

Curtis is sympathetic to both the neocons and the Islamists, because as a self-avowed liberal, he also views today’s Western liberal society as essentially nihilistic, desperately in need of a new vision for the future that will liberate people from their sad, atomized existences. He understandably avoids the difficult work of trying to come up with a solution to our spiritual predicament. Curtis sees himself not as an ideologue, but as a historian, posing the question of how we got here: How did we come to believe in nothing? Reactionary ideologies like neoconservatism and radical Islam are secondary characters in Curtis’s universe. The principal character is what these ideologies are reacting to: a rationalist, technocratic, individualist out of risk-aversion from any genuine politics.

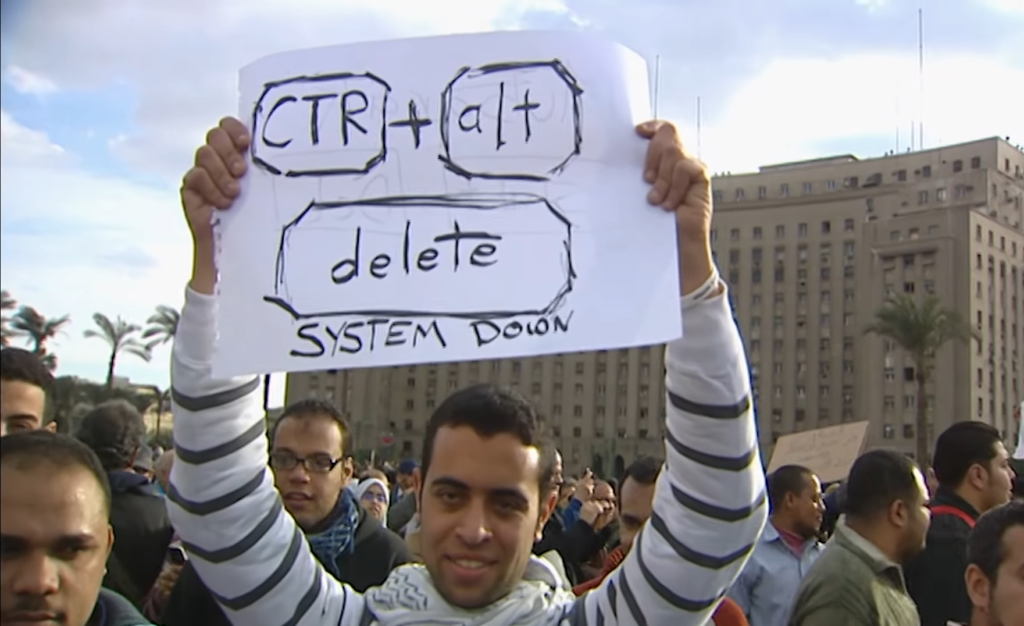

Curtis traces the intellectual and social history of this worldview over the course of the 20th century, from game theory and cybernetics to the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street, via the hippie movement and cyber-utopianism, neoliberalism and New Public Management. The story, in short, is that what started out in the ’60s as an anti-establishment revolt against traditional social structures ended up being co-opted by corporations and right-wing politicians, who both used it to their advantage. Corporations harnessed the desire for authenticity and self-expression to sell people products, while politicians like Reagan and Thatcher channeled it into a revolt against the bureaucratic welfare state and organized labour, giving even more power to corporations. The internet was idealized as a place where people would be completely liberated from social structures and free to express themselves, and everyone joined. But along the way, we lost any sense of society as a collective, rather than the sum of its individual members, and without any sense of collectivity, people were no longer able to imagine how they could work together to change society. Their utopia of freedom had been achieved, and they could go no further. Meanwhile, corporations exerted more and more control over the lives of individuals, who spent their time staring into electronic mirrors and sliding deeper and deeper into passive narcissism, and in the absence of any genuine politics, society became a technocracy, ruled by managers. And by the time of Occupy and the Arab Spring (about which Curtis probably generalizes too much), people had lost the ability to formulate a positive political programme, instead practicing a purely formal kind of prefigurative politics.

Curtis’s best work—2002’s The Century of the Self, 2007’s The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom?, and 2011’s All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace in particular—develops this central thesis. But the project began much earlier, in 1992, with a six-part series called Pandora’s Box on the theme of technocracy. Pandora’s Box starts with an autopsy of the recently-collapsed Soviet socialist system, which in Curtis’s view fell victim to its own faith in science and technology. Beginning with the first five-year plan, Curtis goes over the history of the Soviet Union’s fetish for technology and its strategy of centralized planning. Gosplan, the central economic planning bureau, was tasked with creating and administering the five-year plans, setting production quotas and monitoring their fulfillment, based on a huge quantity of data. But the plans, around which the working lives of Soviet citizens were organized, ultimately became a joke—everyone knew the figures on which the plans were based weren’t real, because almost everyone was involved in manipulating them.

Fifteen years later in The Trap, Curtis looked at what happened in Britain with the introduction of the techniques of New Public Management, which began in the ’80s under Margaret Thatcher and then expanded under John Major and Tony Blair. Ironically, it ended up looking quite similar to what happened with the Soviet command economy—although Curtis doesn’t explicitly compare the two. The British government sought to make public services more efficient by setting targets tied to rewards for individual public servants, encouraging them to act in their self-interest, rather than for the public good, since it was assumed that they would act selfishly anyway. What happened again was rampant manipulation of numbers by cynical bureaucrats, policemen and hospital managers looking to meet their targets in “innovative” ways.

In HyperNormalisation (2016), made almost two and a half decades after Pandora’s Box, Curtis revisited the Soviet Union, using some of his original footage, and took another look at what was going on culturally in the late years of Soviet socialism. He borrowed the film’s title from anthropologist Alexei Yurchak, who used it to describe the late Soviet condition. People no longer believed in what their politicians told them (that everything was going according to plan), but they followed along, because they could not imagine anything different. The general mood was one of cynicism and pessimism. Curtis argues that we in the West are in a similar situation today. We have little faith in the political system and in the authoritative interpreters of reality—political parties, the media—but we cannot imagine a world in which things are better in any meaningful way.

One could easily charge Curtis with being overly pessimistic, or even willfully ignoring the compelling political visions that are sitting in plain view. What about Bernie Sanders’ vision for a democratic socialist United States, which inspired a huge outpouring of support from ordinary Americans disillusioned with politics? What about Jeremy Corbyn’s election to the Labour Party leadership in the UK? In 2015–16, the movements behind both figures showed that a genuine, popular, progressive politics was possible. But Curtis left them out of HyperNormalisation, and it’s not completely clear why. The most likely reason is that they didn’t fit the thesis: The film is about how politics has become reduced to a cynical game based on the manipulation of reality and a disregard for the truth, best exemplified by the strategies of right-wing politicians like Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. Sanders and Corbyn, on the other hand, are honest men, with perhaps too much of a naïve faith in people’s inherent rationality. Did Curtis see the defeat of both movements coming? He may well have, for the faith in reason that Sanders and Corbyn exhibited is something that has comprehensively failed in the past, and Curtis is well aware of that.

There are important lessons that people on the political left can learn from Curtis’s films, and maybe they are even beginning to do so. One of the most inspiring moments from Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign was at a rally in Iowa, where campaign surrogate Phillip Agnew led the crowd in a powerful ritual of solidarity. Members of the crowd joined hands with their neighbours, eyes closed, and followed Agnew’s instructions: “If you’ve ever wondered where your next meal might come from, please squeeze your hand … If you’ve ever fallen ill and ignored it because the bill might hurt more than the ill … If you’ve ever been pulled over by a police officer and prayed to God that you’d make it home … If you’ve ever gone to war with your mind …” This is precisely the kind of collective, emotional, spiritual, irrational politics that Curtis is calling for, the kind of politics than can break the spell of individualism through visceral communion. It’s the style of politics that the neoconservatives and radical Islamists practiced, only instead of creating solidarity through fighting a holy war against an external enemy, it creates it directly, joining individuals together first, in a positive affirmation of fellow-feeling from which a shared struggle can follow. Sanders’ campaign slogan, “fight for someone you don’t know,” had the same quality, pronouncing that politics is a collective struggle for justice in which we are all engaged and directly responsible, where we can give ourselves up to a higher purpose.

Curtis, like many liberal commentators, is careful to point out the dangers inherent in such idealistic forms of politics, which are fundamentally about changing human nature and creating a New Man (the history of the 20th century is littered with their casualties, as he frequently points out). But at the same time, he sees it as a duty to face up to the danger and dare to imagine a world inhabited by a different type of human being. Because if a new collective spirit doesn’t prevail, a darker ideology will take that dissatisfaction and harness it for its own ends, and we could well end up in a nightmare rather than a utopia. Curtis’s message is that we need big, spiritual, existential ideas—dangerous ones, about what it means to be human and what it means to be free—in order to do so.