50 years ago, in January, 1972, the BBC aired the provocative miniseries Ways of Seeing, which explored how the camera and the widespread use of photographs altered our perception of art publicity images, including the representation of women and the male gaze.

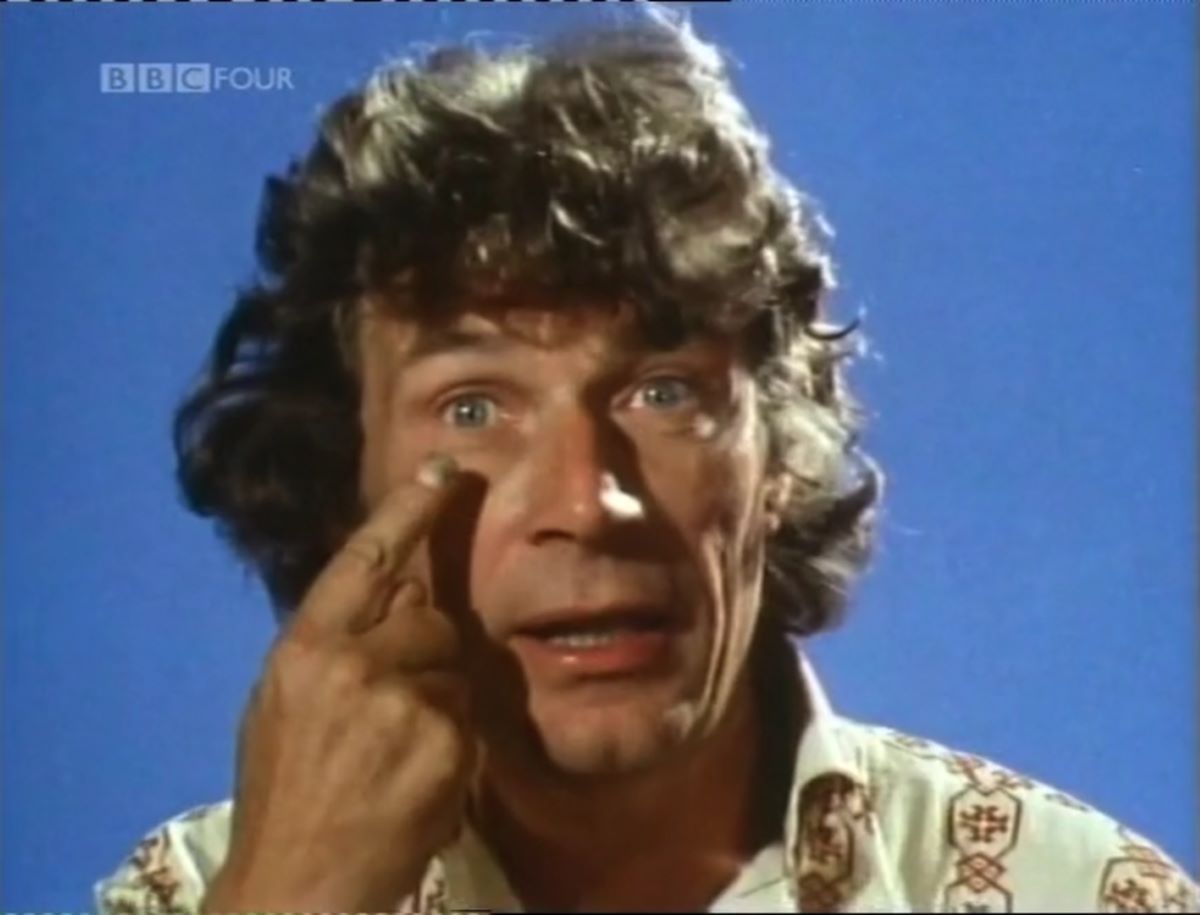

The writer and host of the program, John Berger, declared: “With the invention of the camera, everything changed.” Middle-aged at the time, with a mane of long, curly hair, wearing an inexpensive chain-mail print shirt, collar unbuttoned, Berger did not look one bit like the stuffy art critic a viewer might have expected. Drawing on the work of Russian pioneer film director Dziga Vertov and German cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, Berger stated authoritatively, in sonorous tones that, for the first time in history, “We could see things which were not there in front of us. Appearances could travel across the world.” Brought to us by the camera, we no longer had to visit museums to view paintings, because the paintings would come to us through photography. This was a startling revelation and forever altered our perception of art.

Directed and produced by Michael Dibb, Ways of Seeing took the BBC by surprise and became a television sensation, garnering awards and critical accolades. Berger and Dibb, the co-creators of the series, were little known beyond the literary and cultural scene in the orbit of London, though each would become influential, as a writer and as a filmmaker, respectively.

Soon after, Ways of Seeing was published as a pocket-sized paperback. Profusely illustrated and innovatively designed, the publication was dubbed the world’s “smallest art book.” A classic, it is credited to five people: Berger, Dibb, book designer Richard Hollis, Sven Blomberg, and Chris Fox. The book enjoyed considerable international success, and became a staple in university courses. Berger became known as an art critic whose opinions were as unorthodox as the garish and iconic shirt that he had worn on television.

The television miniseries was the first of numerous collaborations between the two artists. Yet, after careers of 70 and 60 years respectively, each has remained an unsung hero, though Berger, who died at age 90, arguably has been enjoying an increasing aura of adulation in recent decades in artistic and literary circles. Dibb, who is 81 years of age, has remained relatively unknown, especially in North America, where Ways of Seeing has been popular as a book but unknown as a television series. Before the Internet, television documentaries had limited availability, and, sadly, documentarians like Dibb did not enjoy the international reputation that they deserved.

Berger, whose professional career began as a painter, wrote art criticism and political articles for The New Statesman, the leading independent and progressive political magazine of the UK. He quickly gained a reputation as a left-wing enfant terrible of literary circles, a visionary with a radical, poetic, and compassionate view of the world. In 1972, when he was awarded the Booker Prize for his novel, G, Berger scandalized conservative Britons by sharing the prize money with the London branch of the Black Panther Party, which was involved with the struggle in Guyana, the seat of the Booker corporation’s sugar interests. He matter-of-factly explained that “the prize is given by Bookers, who are a firm who have extensive trading interests in the Caribbean for 130 years. The extreme poverty is the direct consequence of the exploitation of companies like Bookers, and others. And so, I intend as a revolutionary writer, to share this prize with people in, and from, the Caribbean, people who are involved in a struggle to resist such exploitation, and eventually to expropriate companies like Bookers.”

He kept the other half of the prize money to fund his future book on migrant workers in collaboration with Swiss photographer Jean Mohr (A Seventh Man, 1975), an action consistent with his own political struggle. To the best of my knowledge, no other author in the English-speaking world has ever shared a major literary prize with a political group.

Feeling somewhat like a cultural outcast, in the mid-’70s Berger moved to the small village of Quincy, in the Haute-Savoie region in the French Alps, where he and his third wife made their home among the peasant farmers of the region for more than four decades. Although Berger was born into a prosperous middle-class family, he had no formal post-secondary education except for a brief stint in art school. He credits his beloved farmer friends with having given him a“university” education.

“My professors and my tutors were the men and women of these villages and these farms. They educated me, and I learnt from them…About how to deal with life, how to live, how to live together. All kinds of codes of behavior: about hospitality, about tact, but also equally about the nature of violence, and jealousy. And intolerance…I don’t want to idealize these people. At all.” Berger’s experience with life among the peasants gave rise to Pig Earth, a novel that Dibb made into a documentary in 1979.

The scope of Berger’s artistic achievements is nothing short of sublime: In addition to his broadcasts and drawings, he published over 70 books, including many collaborative works: novels, poetry, essays, plays, art criticism, and countless articles on a wide range of subjects, from migration and revolutionary movements to literature and art. As an essayist and broadcaster, he is respected not only for the originality and intellectual rigour of his arguments, but also for his remarkable ability to explain complex existential ideas with language that is both accessible and poetic, rational yet soulful. After all, in his heart of hearts, Berger was a storyteller. “If I am a storyteller, it’s because I listen. For me a storyteller…is like a passer. That’s to say, someone who gets contraband across the frontier.”

Like Berger, Dibb went on to become innovative and influential. He has directed and/or produced close to 100 films, and is regarded by some as “perhaps the greatest documentarian of his generation.” He is especially recognized for pushing the boundaries of the television art documentary genre and transforming it into the “film essay,” initially at the BBC and later through his own production company.

His films on artists, writers, musicians, and thinkers—Antonioni, Godard, Octavio Paz, Studs Terkel, Keith Jarret, Miles Davis, Edward Said, and Astor Piazzola, to name but a few—were far from the informational and purportedly “objective” documentary genre that was typical of television in the 1960s and ’70s. As he stated in 2012, he “wanted to demonstrate that the film essay needn’t have an inferior status to the written essay. He told Sukdhev Sandu, in The Guardian: “In my film In Pursuit of Don Juan (1989) you hear poetry about him, see images of him, explore his historical roots in Spanish culture: a rich brew. It might even give you more things than a written essay ever could. I’d like to feel my film might be as valuable a 75 minutes as you could possibly spend reflecting on the subject.”

Invariably his films are compelling statements, infused with his own radical point of view, his own political position. His film essay, The Spirit of Lorca (1986), is not only a historical telling of Spain’s greatest poet, but an unequivocal condemnation of the fascist regime of Francisco Franco that savagely killed the poet at age 38.

In a brilliant sequence of cinematic storytelling, Dibb so deftly prepares the audience for the moving climax that viewers anticipate the moment with bated breath. As he retraces the final steps of Lorca’s death, the voices of a women’s chorus, off screen, are piercing shrieks, as they chant the words of one of his most famous poems, “Los caballos son negros.” Their wailing is the raw sound of despair, juxtaposed with silent archival footage from the Spanish Civil War of women keening inconsolably over the bodies of their murdered boys and men.

It is a story whose ending we already know, yet we are deeply affected, for the power of the story lies in its telling, in the way that the filmmaker effortlessly moves our spirit and embeds the story in our minds. Dibb’s talent is that he is able to quickly “find the voice of the story.” He might have learned that from Berger, whom he began to assiduously follow in The New Statesman. To be a good storyteller, Berger says, one must first find the voice of the story, as he did with the French peasants whose stories he immortalized in Pig Earth, the first book of his trilogy called Into Their Labours.

Introduced by an intellectually rigorous essay, and interleaved with poems, Pig Earth is a lyrical account of the way of life of the peasants in the Haute-Savoie, who became the author’s friends and neighbours. The work reads like a novel but it has the feel of a documentary. But unlike a film documentary, there are no moving images, no photographs, nor recorded audio. Berger lets us imagine these things through his moving words, so moving that they seem to literally get under one’s skin. Through his descriptions and reflections about the lives of the peasants, he transmits the compassion and respect that he feels for them.

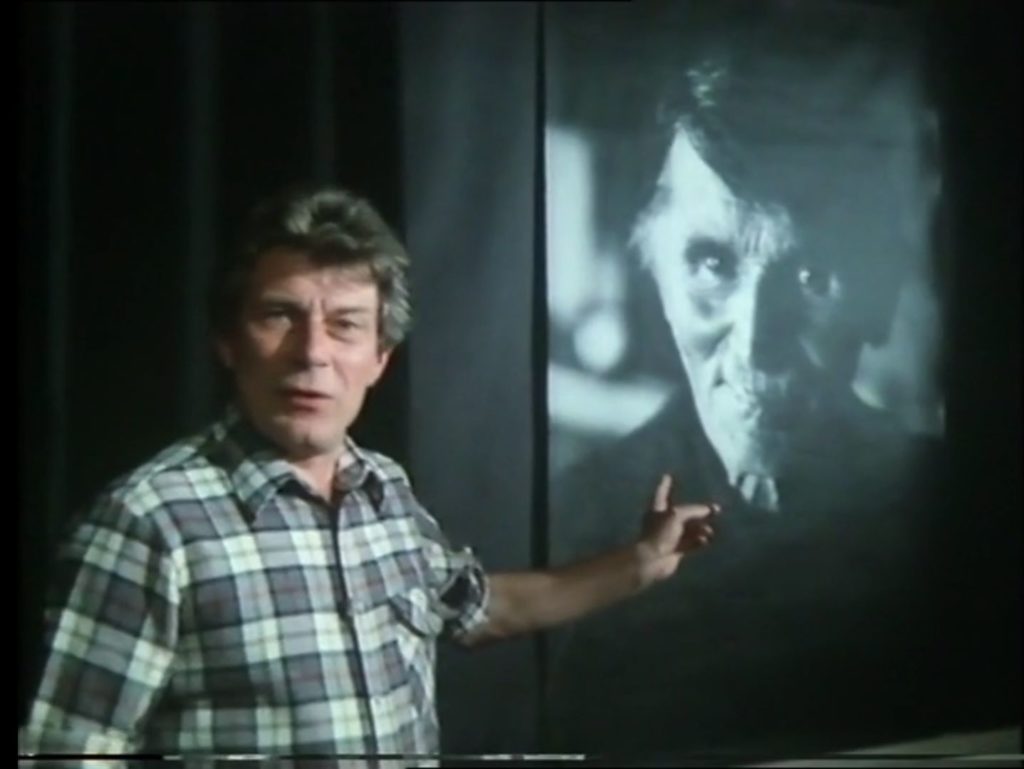

In transforming Pig Earth into a film essay, Dibb relies heavily on photographs of the same peasants in the Haute-Savoie, made by Jean Mohr in collaboration with John Berger, for Another Way of Telling, a landmark book. In it, Berger posits his theory on the relationship between the photograph and the written word: “The photograph begs for an interpretation, and the words usually supply it. The photograph, irrefutable as evidence, but weak in meaning, is given meaning by the words. And the words, which by themselves remain at the level of generalisation, are given specific authenticity by the irrefutability of the photograph. Together the two then become very powerful…”

Dibb illustrates this theory and expands upon it through the elements of cinema when he transforms Pig Earth into a film essay. He is a master at mixing still photographs, film clips, movement, narration, and sound—key elements in the language of cinema.

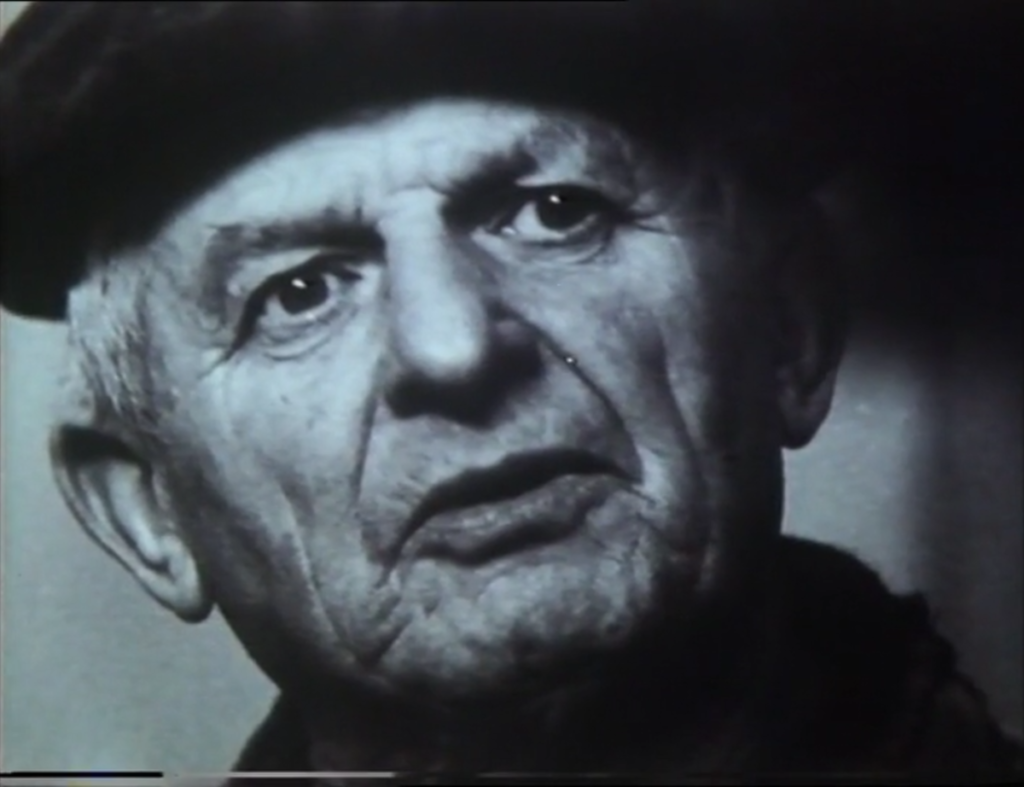

The film opens with a photograph of two hands which fills the entire screen. The hands are folded, clasping the handle of tool. It is a black-and-white image, and though out of context (and therefore ambiguous) it implicitly tells us something about the spirit of the film we are about to see. The next shot is a film clip, in colour, a portrait of the man whose hands we have just seen. The narrator, John Berger, says off-screen: “This man is called Téophile…he’s a French Alpine peasant.”

Moments later, another still photograph fills the screen again, a close-up of three fingers, just as Berger’s voice implores us to understand that which “constitutes peasant experience.” The peasant’s life experience is encapsulated in the rough-looking skin of these labouring hands, fingernails blackened, encrusted with dirt. The camera slowly zooms out, and reveals the earlier image that opened the film. But this time, we hear an accordion—a soft, plaintive sound that will be repeated throughout the film. We soon realise that this is a sound through which French Alpine peasants express some of their joys and sorrows, and so situate their lives. In this brief segment, the filmmaker has already found the voice of the story.

In another unforgettable sequence, Marcel, the cow herder, helps one of his cows calve. Berger’s voice, again: “His hands were trembling as he tied the rope around the forefeet. Two minutes pulling, and the calf was out. Safe. Female. He rubbed her down. For him, these moments are moments of triumph.” As these words are spoken, the camera focuses on a still photograph of Marcel, his face full of tension. In a slow, panning action, the camera follows Marcel’s extended arm, bit by bit, until it reveals his hand pointing to the cow. His forefinger is extended, outlined brightly against the dark background. The moment is intensely dramatic, as if we had witnessed the birth ourselves. From the labyrinth of our memory, we recall similar pictures, something biblical about the miracle of birth. The photograph of Marcel was given another level of meaning by the words spoken over it.

Artistic collaboration can be challenging. Personal ego cannot stand in the way, for one may have to change one’s mind, if necessary, as happened during the making of Parting Shots with Animals (1980). Directed by Dibb and Chris Rawlence and based on Berger’s essay “Why Look at Animals?,” the film is an exploration of human perception and treatment of animals.

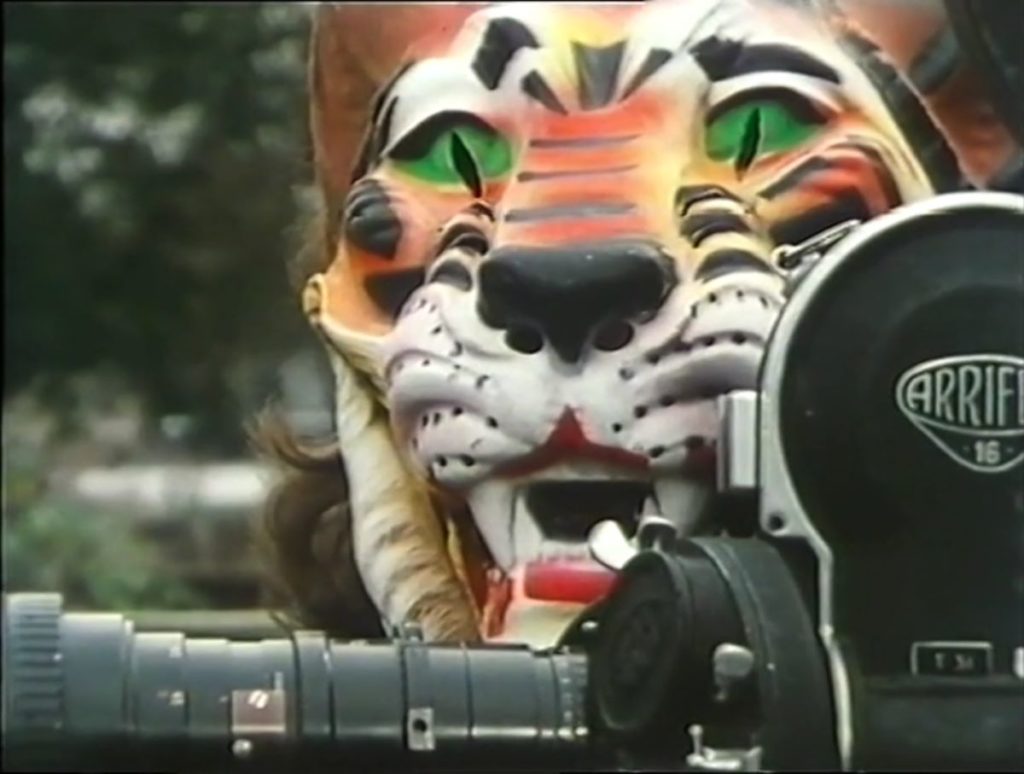

The shooting was already quite advanced when Berger suggested to the filmmakers that it would be more effective if the premise was reversed: What if the film were made from the point of view of the animals looking at people? In true collaborative spirit, the filmmakers went one step further: They bookended the film with shots of the crew members wearing animal masks as they filmed on location. Berger’s voice opens the film: “We, animals, are disappearing. We have made a film. Not so much what remains of us the animals, but of you, the people. Make no mistake. We are not victims. We are animals. We are going back into the ark.” It is an impassioned manifesto, a cri de coeur from animals.

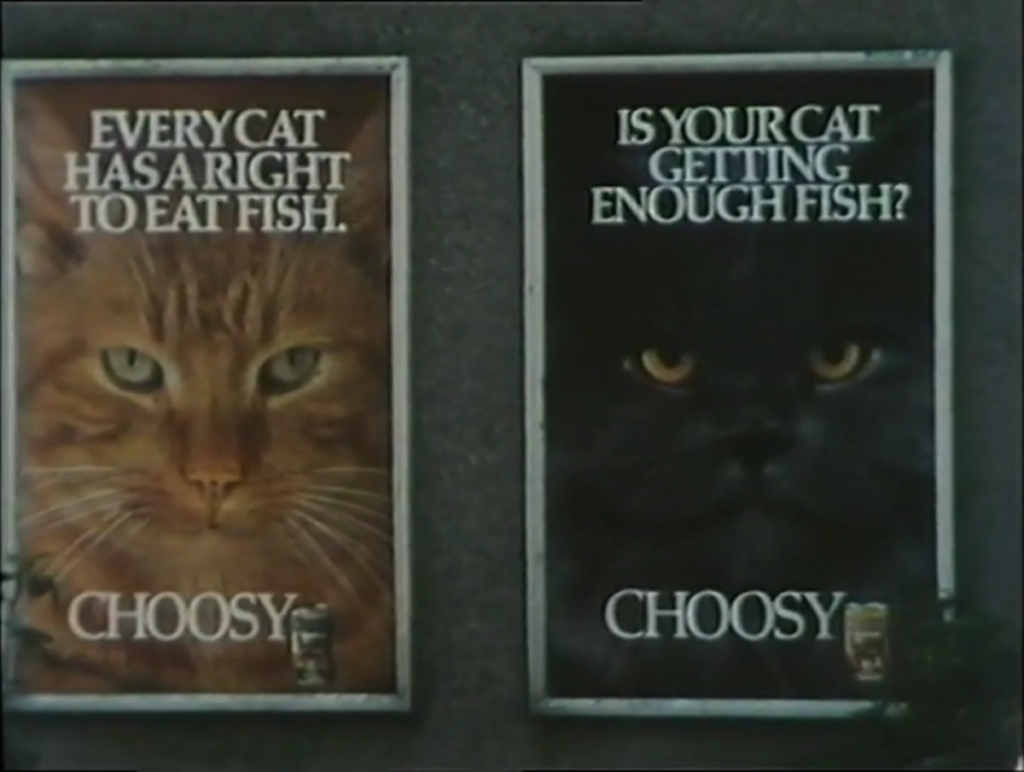

What follows is a series of eloquent images and vignettes that speak of animals in zoos, on farms, at slaughterhouses, but in their voice. Throughout, we hear an eerie, droning sound, as if presaging impending doom. Dibb’s filming throughout is as visually impactful as Berger’s words are poetic, including shots of Clydesdale horses hard at work, plowing a field against the backdrop of a nuclear reactor. The film is elegiac and ironic in tone, brilliant in its analysis of how humans exploit animals, and prescient of the climate crisis.

In a truly collaborative process, respect for the other is crucial, as artists become full and equal participants. Dibb reflected on his intense working relationship with Berger, and was greatly moved by his colleague’s generosity. In particular, he recalls a letter that Berger sent him during the making of their television series, in which he urged Dibb to “Criticise, improvise, change, improve, cancel out, as much as you want or see how to. Or even we can begin again. All I would stand by is the essential idea…” In an interview with Yasmin Gunaratnam in January 2021, Dibb summarized his collaborative relationship with Berger as being “sui generis…the way I worked with John is different from almost everybody I ever worked with…what one is generating with John is a dialogue, because even though he often says things as if they’re statements, in a way they’re always questions, but he’s anticipating a response.”

Berger and Dibb both recognized the importance of dialogue as the enabling mechanism through which they could exchange intellectual and artistic ideas. Their objective was to tell stories in a different way; they sought and succeeded in creating sublime points of intersection between literature and film. In doing so, they elevated their stories to ever greater emotional power while endowing them with universal appeal.