“ The contemplation of things as they are, without substitution or imposture, without error or confusion, is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of invention.”

— FRANCIS BACON

Phil Bergerson’s distinguished photographic career has been completely entwined with art and education. After abruptly deciding to quit teachers’ college one week before graduation in 1968, he was at loose ends until he read Helmut Gernsheim’s History of Photography. “A little paperback…and it just blew me away,” he recalled recently. “It spurred me on to think that I could become an artist if I used a vehicle like photography.” He enrolled in the Photo Arts Department of Ryerson Polytechnical Institute (later Ryerson University, which [was] renamed [Toronto Metropolitan University] in 2022 in the spirit of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples).

Over the years since he decided on photography as his métier, Bergerson has become an artist of international renown and a much-loved and respected professor at Ryerson. Ironically, before becoming an artist, he had to become a passionate teacher of photography. The one informed and inspired the other. At first, the two overlapping paths in his career created enabling conditions for Bergerson’s creative work. But in time, his educational and related organizational activities became a constraint towards fulfilment of his dream of becoming an artist.

Bergerson’s achievements as an educator were prodigious. As a professor, he had the credibility of the institution behind him, and the wherewithal to “make things happen,” as he has noted. He began by inviting W. Eugene Smith, the American photojournalist, to speak at Ryerson in 1975. Smith had worked at Life magazine and his reputation as a photo essayist had reached almost mythical proportions. It was an audacious move, and the 350-seat auditorium was packed. The audience was enraptured as the emotional Smith, in tears and between sips of whisky, explained why he considered his iconic photograph, “Tomoko in the Bath”—his “Pietà of the 20th century”—a “failure.” He felt that it could not possibly convey the depth of suffering of the young girl, who was tragically born with severe disabilities after her mother had unknowingly ingested fish contaminated by mercury effluent. Now it was the audience who was in tears (including the author of this article). This is the kind of cultural experience that Bergerson introduced to Toronto. He set the bar high. By 1989, he had invited 112 speakers: photographers, historians, theorists, curators, experimental filmmakers, media artists, and educators.

Ever prescient, Bergerson acquired a number of Smith’s prints for the school’s resource centre using personal funds. He did the same with a few other photographers, and thus helped to lay the foundation of what would become one of the most significant collections of original photographs in the country, now under the stewardship of the Ryerson Image Centre.

Bergerson sensed the need for a major critical discourse in Canada’s photography community to counteract the country’s sense of isolation and regionalism. With the help of his students, in 1979 he organized “Canadian Perspectives: A National Conference on Canadian Photography.” Once again, Bergerson had the sagacity to push the conference, metaphorically, outside the walls of academia. Two dozen speakers were assembled from across the country, and between the animated and sometimes fierce debates, the conference became a catalyst to a collective awareness in the burgeoning pan-Canadian photo community.

Bergerson’s early work was eclectic, including painting, etching, and conceptual photography based on the manipulation of materials. His “Untitled [Mother and child diptych],” a conceptual piece from 1974, is described as an “underpainted solarized Kodalith over scratched text on metal plate.” Technically exacting and brilliant, his work was more about process and materials than content.

Inspired by the work of Michael Snow and Hilla and Bernd Becher, he began to arrange photographs as typologies within a single frame. His “Untitled [Turquoise House]” (1985), is a composite print of 64 views of a small house, from the same vantage point, but with the camera progressively shifted slightly with each frame. His “Body Grids” consists of naked body parts, isolated and decontextualized. “Genitalia” (1986), from this series, is a grid of 56 frontal views of the lower part of men’s bodies. As Peter Higdon observed, it became somewhat notorious as the “penis picture.”

Although his work was published, collected by institutions, and exhibited internationally, Bergerson felt that he had arrived at the “end of the road.” He had done as much as he could at “playing at being an artist…learning [his] chops…and what the history was.” It was time to move on. In 1987, he spent a few days with Frederick Sommer at his home in Arizona. Sommer, whom Bergerson had invited to speak at the Ryerson lectures, was a multi-disciplinary artist, whose practice included photography, painting, drawing, collage, poetry, and musical scores. The visit was a life-changing interlude for Bergerson, who was immeasurably moved by “the spirit of the man.” He credits this visit as a catalyst that propelled him to re-align his creative compass.

By 1989, Bergerson had begun to photograph in a straightforward manner, in the social documentary vein. A complete departure from his previous work, it was a leap of faith that took him back to the origins of the medium. His new photographs were neither altered nor manipulated, “dodging all that ‘crazy’ theoretical stuff,” as he noted recently.

For the next 30 years, he photographed in small towns across the United States, exclusively in colour. He focused on aspects of the urban landscape, seeking the remnants of human activities in shop-window displays, random signs, graffiti, murals, pictures, and the edges of the social landscape. The images capture the explicit messaging left by others, which express outrage or joy about life, consumer products, entertainment, religion, guns, politics, patriotism, or historical lore.

In Shards of America (2004), Bergerson chose 90 photographs to represent this period of social and media documentation. The entire collection of images is like a visual archeological hunt of American culture, as historian David Harris suggested in his introductory essay. Ten years later, Bergerson published an expanded collection, American Artifacts, with essays by Margaret Atwood and Nathan Lyons. This was followed in 2020 by Phil Bergerson: A Retrospective, a sumptuous volume with essays by Peter Higdon and Don Snyder, both colleagues at Ryerson University.

In looking at his pictures, it’s as if he has taken the viewer along on his odyssey across the United States. The photos represent an agglomeration of at least 68 trips over several hundred towns and cities between 1995 and 2018. The images are dynamic and bold in terms of graphic elements, and it is easy to feel as if you were standing exactly on the spot where the photographer placed his tripod.

The photographs do not have revealing titles or explanatory captions, save for the name of the town and the year. Bergerson isolates the subject from its surroundings, providing little or no context. He is interested in communicating the very essence of the “found” messages, which he is re-interpreting through a combination of scrupulously exact compositions in square format (until recently) and with a patina of colour that he has captured.

At first reading of his landmark books, this is an America that we have seen, or at least an America that we have imagined. But a circumspect re-examination of the images reveals a multiplicity of layers. “Orlando, Florida” (2001) documents a mural on the side of a one-storey building next to a parking lot, on which a cowboy is riding with wild abandon, rifle in one hand, whip in the other. The rider is silhouetted against a lush orange-red (western) sky. A parked car is on one side of the frame, and a one-way traffic sign is on a thin pole planted in a plastic bucket. The arrow on the sign points to the rider who is traveling in the same direction. An American flag flutters in the wind but is distorted by the long exposure. Above the rider is an elegant sign in the form of an opened scroll that says simply, “Winchester.”

By juxtaposing these components, and using them as symbols, Bergerson has made an astute and complex statement on patriotism, gun culture, television, and photography. The rider is an allusion to an icon of American culture, the Western. The horse’s hooves are all above the ground, which is the accurate way of representing horses in motion, proven by photography in 1878, through the work of Edweard Muybridge. The horse is also contrasted with its modern counterpart, the parked automobile. The tattered flag is a veiled criticism of America. The arrow on the sign points in the direction that the rider is going. Implicitly, there is only “one way” possible, and that is the American way. The pièce de resistance is the Winchester sign that declares this image to be a sleek corporate ad selling guns. It is a breathtaking piece of vernacular art, but Bergerson has revealed hidden layers of meaning.

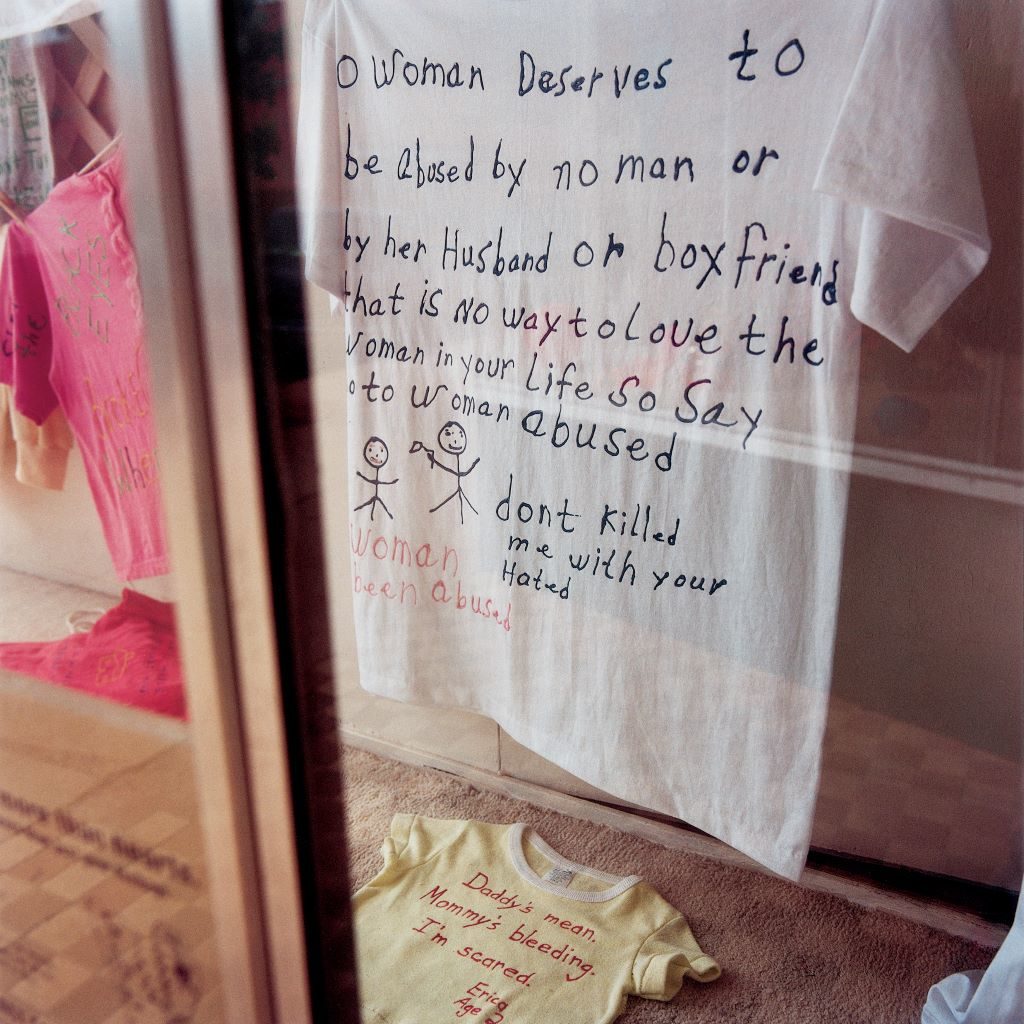

Many of his images foretell the current social problems that plague the United States. In the photograph “Wichita, Texas” (1998), a t-shirt hanging in a window contains a poignant message of abuse against women, in child-like printing: “No woman deserves to be abused by no man or by her husband or boyfriend…” At the bottom is a child’s “stick” drawing of a man and a woman. The misspelled caption describes the drawing: “woman been [being] beaten.”

Another image, “New York, New York” (2002), is of a drawing on a wall that depicts a uniformed police officer holding a large gun to the side of the head of a man in handcuffs, who is clearly a person of colour. Will the cop shoot him? Sadly, the scene recalls cases of police brutality and racism that have rocked America, in particular the murder of George Floyd in 2020 by an officer.

But Bergerson’s voyage is not completely grim. The first image in both Shards of America and American Artifacts is a ticket booth in front of a movie theatre, “Springfield, Missouri” (1998). The curved glass window says “welcome” in cursive letters. On top of the booth is the word “Life,” huge, in bold letters. “Life” is a word that resonates deeply in American culture, and which is also embedded in the history of photography. It was the name of the most important American visual magazine in the 20th century, a weekly that was profusely illustrated with the work of the world’s best photojournalists, and which came to represent the identification of America to itself and the rest of the world. Bergerson recalled that he knew instinctively that it was about the beginnings of a visual voyage during which he would “explore the life of the people of the United States…and the first thing that hit me was Robert Frank,” the Swiss-born photographer who famously took a road trip across the country in the ’50s.

“At the heart of the road trip,” Bergerson says, is the “American dream” that he seeks to capture. “It is the freedom of being on the road. It’s tied directly to the car and the freedom of the car…I always thought I was actually living part of the American dream just being in my van, driving everywhere, all over the United States all those years.” He was not afraid to get lost, taking the wrong road in the backwoods of America, ending up in the wrong town. Perhaps taking a cue from American poet Robert Frost, Bergerson learned that his journey was not about arriving at a destination, but about the road taken or not taken.

One of his most important pictures was the result of being in the wrong place, but at the right time. “Pocatello, Idaho” (2007), which is the cover of American Artifacts, is a junk yard that he happened upon by chance. He immediately realized that it was going to be the image that could symbolize his version of American dream in all its contradictions. He quickly and instinctively set up his camera, but his heart was racing. “I’m shaking, terrified that someone is going to come and stop me…Everything that I had learned in the past 40 years came to bear on the construction of this picture.”

Stepping into the scene, you see a car, that quintessential symbol of American culture, except that it is dented and ready for the scrap heap. Yet it sits on top of a rail box-car, like a prized display at a country fair. The box-car itself serves as a canvas for an idyllic painting of a mountain scene with a lake and green meadow. That fictional scene is contrasted with the real mountains in the distance; Bergerson purposefully raised his camera to let the mountains protrude slightly above the horizon. In the foreground lies a dirty mattress, symbol of the cycle of life and death. A cement factory looms high in the background, complete with an American flag on top. It is like a man-made mountain and speaks of the power that American industry has over the environment.

He made his exposure without anyone coming to disturb him and breathed a sigh of relief at having photographed the “the epitome of so much that I had been working on for so many years…” The artifacts in that junkyard are the residues of consumerism in American culture—the other side of the American Dream.

When Bergerson switched from analog to digital, he also switched from the square format to the rectangle (landscape format). He no longer has to exclude as much as he did when he used the square ubiquitously, which makes his recent work markedly different. It is more positive and nuanced, suffused with a warm ambiance of America as a safe haven. His “Newmarket, Virginia” (2018) is a dilapidated wood porch, bathed in the soft light of morning. But unlike his earlier pictures, this is not a shard; it is a home, aged but not broken down. It conveys a welcoming mood and country serenity. The “beware of dog” sign is tucked in the corner, almost out of sight, while the floor mat says “welcome.” A weary traveller would easily feel welcomed in one of the modest chairs, and not feel like an intruder. This is also part of the American dream.

With his extensive documentation of American artifacts, Bergerson has succeeded in making a personal portrait of the United States, one that poses more questions than answers, challenging viewers to look beyond the surface. It is important to see his photographs in the form of photo books, for they have been meticulously sequenced in a particular order. Consequently, the significance that we derive from one individual image is influenced by the meanings that we derive from the preceding image and the image that follows it. Sequenced as part of a collection, in book form, each photograph gains another dimension, transforming it from a single image into a component part of a larger statement. The book of photographs is, in and of itself, the work.

Bergerson followed the road travelled by Walker Evans and Robert Frank, seminal figures whose lifetime work also took the form of photo books. Evans’ American Photographs (1936) and Frank’s The Americans (1958) became two of the most influential classics. Bergerson’s American Artifacts is a modern-day classic that is destined to take its place on the same shelf.

Unlike his predecessors, there are no people in Bergerson’s portrait of the United States. He documented the people’s tragedies, triumphs, and dreams through the traces and detritus that they left behind. He has astutely documented “things as they were,” and that is the strength of his work. In doing so, he’s succeeded in capturing a poetic rendition of the human condition. Phil Bergerson’s work will continue to have significant historical and documentary value in years to come, especially as the social landscape of America inevitably continues to change.