The 2026 Sundance Film Festival may be the final edition for the celebration of independent cinema in Park City, Utah. However, as Sundance moves to Boulder, Colorado for its next edition, the festival continues its tradition of new beginnings. Deals happened with hopefully some to come for the documentary side. Oscar campaigns threw some seeds for a year-long run. Careers enjoyed some big breaks.

The story of the films may have been secondary to the narrative of the festival proper, but Sundance overall came out well in the year this year. To recap their 2026 festival, we’re changing gears somewhat for a conversational approach and calling upon POV’s veteran Sundance kid Jason Gorber to join the conversation and share his thoughts about what the move means for the festival and how the documentary slate compared to other years. He joined Pat Mullen to discuss the vibe and atmosphere that made Park City unique, but also to consider the best films at this year’s festival and what the docs of 2026 say about the business overall.

PM: Pat Mullen

JG: Jason Gorber

PM: 2026 was the final year for Sundance at Park City. I’m a child of virtual Sundance, so, unfortunately, I never got out there properly. What do you think it means for Sundance to be leaving Park City?

JG: The last time I stood in Park City, I was watching news about this virus that was coming from Asia. Being from Toronto and living through SARS, I knew what could happen when a virus like this actually affected people. I had this weird feeling of, not anxiety, but recognition that none of this could be sustained—and 2020 was a pretty good year for Sundance. 2019 was actually great year, but in 2020, it felt like some things were slipping away. Robert Redford seemed a little bit older. Documentaries had been massive, the streamers were coming in more, and so were the people who buy all this stuff. It felt like things were going away and then things went away in a weird way.

PM: And 2020 was when Boys State sold for huge money to Apple.

JG: I love those filmmakers and Boy State is stunning, but this film would’ve had a much more traditional theatrical run and would’ve been seen and would’ve been part of the Oscar conversation, etc. And then suddenly it’s a very different vibe. There was the feeling that Park City couldn’t continue, and Sundance couldn’t continue in the way that it was moving. A change had to be made. And even back then, there were all these bubblings about where it was going to go. As messed up as it is, COVID shut things down. But Sundance was inevitably going to be leaving Park City because it is an incredibly expensive place to hold a film festival. Logistically, it’s a mess. I desperately miss being there, but it made absolutely no sense to go when virtual became a real possibility to cover this stuff. TIFF is seeing incredible challenges about what they’re able to get given Telluride, Tribeca even, but more importantly, Venice. You look at what SXSW is now getting as soon as something like Everything Everywhere All at Once played SXSW and not Sundance and won the Oscar. You’ve seen a massive shift in all these festivals. Boulder might be the opportunity for it to regain its mojo.

PM: I think Sundance has some mojo: all five doc nominees at the Oscars are Sundance 2025 premieres. Train Dreams is a Sundance premiere. That’s up for Best Picture. If I Had Legs I’d Kick You is a Sundance movie. So there’s a bit of movement.

JG: For nonfiction, Sundance is remarkable. It is absolutely still the home of documentaries. The problem is that what happens with those documentaries afterwards has shifted dramatically in the past 10 years. Documentaries benefitted from the feeding frenzy, but Sundance birthed Miramax and Miramax then birthed Focus, etc., and out of that phase you had the Michael Moores, you had the documentaries that would be discussed in the same way that major releases get discussed. The only time that happens now is when it’s the First Lady.

PM: Melania overshadowed the documentary conversation this year, I think. I was going to see it Friday, but since it was so cold out, I just bundled up with Sundance movies and will catch it this week. When we talk about Melania and the way the festival itself has shifted, I don’t know how much you really lose by doing the virtual festival. It seems like the people who were actually there were binge-watching as many films as they could to get in and get out over the first weekend. I don’t really feel like anything “popped” in a way that they might’ve in previous years or that you have much meaningful engagement when the folks on the ground just shoots out a Tweet, moves on, and cranks out some reviews when they get home.

JG: When I went to Sundance, I was there to the bitter end. I was there from the opening to the closing and that gave the opportunity for films to breathe. I was not doing five, six films a day necessarily. But it allowed you to be in line for some of these movies and to interact with people, to have that sense of community. I miss that tremendously. I would love to go to Boulder and to see some of this and my hand might be forced for me if it becomes more and more challenging to actually see things remotely. It’s a catch-22.

But Colorado will be a much easier festival to access. The fact the Egyptian was closed this year at Sundance, the most celebrated and iconic theater, and the only reason the Egyptian was opened at all during the festival was for the surprise wedding of the directors of Nuisance Bear. The festival opened it for them so that they could get married inside the Egyptian. I think that is amazing

PM: And congratulations to them! On two fronts. But OMG who gets married during a festival? I’ve skipped weddings during TIFF. In terms of the venues, I saw Matt Neglia’s picture of one of the screening rooms of Sundance, and I was like, “Even my TV is bigger than that.”

JG: That was part of the charm. Let’s get to a fundamental thing about Sundance: This was started by Robert Redford to have something tiny in his community where he built a ranch. It was great that it built up and became this amazing thing, but it was meant to be this tiny little community thing where people came. Telluride has maintained that scope by being financially impossible to go to. Sundance has this whole notion that is cinema for all. But in doing so, it became untenable to have it in that community. The politics of Utah shifted. It was always conservative, but it really shifted of late and Sundance’s politics also shifted.

PM: Speaking of the politics and the move, did you see the U.S. documentary The Lake? It was funny to see this film about how everyone is leaving Salt Lake City because the lake is drying up, climate change is affecting it, and all this toxic dust is flowing towards Salt Lake City, Park City, and the surrounding area. But in terms of environmental films, it was quite strong as a study of people working across partisan lines, especially given how religious people are in Utah. A lot of characters in the film are from the Church of Latter Day Saints—they pull out the Bible and pray to God that it rains—and there’s a belief in science because of their faith. There’s a lot going on in that film that we haven’t really seen in environmental docs, but a story that’s also productive outside the environmental conversation.

JG: You will find this amusing. There’s all these different venues at Park City, but there was the one called The Temple that I never went to. The temple is way up the highway and I thought that was a Mormon temple. I went there in my fourth year, and it’s a synagogue. But it’s a beautiful space; the theatre is great.

PM: I wonder how they’re navigating programming nowadays. Would they have shown All About the Money in the Temple [given that its subject James Cox takes some hard pro-Hamas/anti-Israel stances in the film]?

JG: One of the things about it being a synagogue is they would allow films to play without editorializing. The encouragement of the discourse is much more important than the restriction of it.

PM: How did you find the slate of docs this year overall compared to other years? I think it ended up being a pretty good year for the docs, but not on par with some of the other years. There was no Come See Me in the Good Light for me this year. Were we spoiled the last few years?

JG: We are in the bubble of the film festival. Even if I love the filmmaker ahead of time or even if I despise the filmmaker, I go in with a certain level of cynicism or at least lowered expectations to be surprised, and when I am surprised, I have a sense of joy. All About the Money is a really good example. I thought the film was incredibly well done. There’s a couple key questions that doesn’t really dive into, such as why Ireland is a place where somebody like him is able to feel at home even more so in the United States, somebody who is so virulently anti-Semitic and his politics veer so far towards the praising of Hitler, and yet a place like Ireland will find a home for him, and an Irish filmmaker refuses to interrogate her own country.

PM: I was interested about her not going there because she’s been quite good about interrogating her own country in other films [Blue Road and Pray for Our Sinners].

JG: This is one of those films showcasing him and his ideas, and giving the audience the opportunity to come up with its own response. That’s what makes it glorious. But there’s nothing more wonderful than for us to take a film that people would’ve otherwise skipped over and to highlight and to champion it.

PM: My hidden gem easily was Closure. I was familiar with the filmmaker, Michał Marczak, who did All These Sleepless Nights, but I was just bowled over by how powerful it was. The premise of the film is a 16-year-old boy is last seen on a bridge in Warsaw, so the choice is either he jumped or he took off and ran away from home. The father decides that he thinks the boy jumped, so he spends two years dredging the river looking for a body. The film follows him day in, day out as he’s turning over anything he can. It’s just devastating because you see how much the family is doing to find him and the way that not knowing what happened eats away at the parents. But it’s also just incredibly well done. It was certainly the most elevated cinematography that I saw at the festival, which made it a respectful portrait of grief that showed people that if they don’t think their family or network is going to be there to help them, they are—because you just see how much they’re doing now when they think he’s gone. It just devastating

JG: One of the things that we do is we divide and conquer, and so I miss some of these great films. Cookie Queens is less of a hidden gem than a film that you assume you know what it is going to be before you see it and that can shift slightly, but I know the producers as the team behind Gaucho Gaucho and Truffle Hunters. They had let us know about the project ages ago. I didn’t know the filmmaker at all and I thought I’d be watching precocious girls selling cookies, yet it turned into this amazing thing about capitalism, greed, adulting–it’s a terrific, terrific film. Then you have something as middling as The Oldest Person in the World, which ended up being just fine at best—certainly not living up to what that story deserved. There’s nothing more crushing than a failed nonfiction project because this is one of the only opportunities you can actually have to actually deal with this subject in a serious way.

Even the way it’s structured, which shouldn’t necessarily work, the going-back-in-time worked beautifully in Broken English, about Marion Faithfull, which is done in a hybridized fashion. This Ministry of Forgetting with people like Tilda Swinton and George MacKay reflecting not only upon this one artist and her work, but on the very notion of what it is to reflect upon archival documentaries.

It’s a documentary about documentaries, which should be terrible, and yet it’s kind of awesome. Similarly, it’s not like we don’t know Mark Cousins’ shtick by now. Hearing his Northern Irish brogue do its thing and we’re used to that now with Story of Film and Story of Women of Film, and yet I found the first chapter of The Story of Documentary, because it’s a documentary about documentary, the most fascinating collision with form. I go back to Wiseman‘s National Gallery, which, what you do at a gallery is you sit and stare at things until you find something profound, and what you’re staring at is the perfect collision between form and content. It’s finally Wiseman at his most Wiseman-esque. Mark Cousins doing a documentary about documentary is glorious in that way.

PM: I’m glad you mentioned Broken English. That was one that had been on my radar mostly because it’s a hybrid film with Tilda Swinton, but I was cautious because I’m so sick of these boomer music docs. But I found that I learned so much about Marianne Faithfull because it really engaged with the story and it brought other people into it with an authentic look about the effects of her music, but also the fact that it captured her final performance. How much of her story would be lost if they weren’t making this film? It’s an incredible work.

JG: It’s like The Last First: Winter K2. It’s a mountain climbing movie about tragedy on top of mountain. We’ve seen this a gazillion times and when it’s done well, you can get some glorious things. The Last First is a fascinating geopolitical tale that has much more to do than with its specific subject, and that’s what I look for: a film that, superficially, you think is going to be one thing but becomes another. Even a non-successful film like Hanging by a Wire, which is a bit of a mess made under incredibly complicated circumstances, telling a story in a community where the telling of stories is restricted. Pakistan is very restrictive about what can be said and, between the lines, literally between the wires, I think there’s more to that film. I have a hope that there’s a better film.

PM: I agree in that I’m sympathetic to the circumstances that make the film limited, but the story raises so many questions and they didn’t go to any of them. That was the one film that I was genuinely surprised was in competition. It felt beneath the calibre they’ve set. I mean, the drone footage is incredible and the rescue story is great, but–

JG: –It’s in competition because it’s from a region that is underrepresented and its restrictions can be excused in the broadest sense by where it was shot. It could have been this, but it being a competition film is almost unfair for the film, which is to your point: it’s half a film. It is not much more than the news reports. It’s making point to show how it’s exploitation.

PM: When there are ten films representing U.S. documentary and ten films representing the rest of the world in competition, there’s a certain calibre that I think they have to consider. Surely there was a film made in equally limiting circumstances that could have brought more to the table. Birds of War and One in a Million were made under very difficult circumstances in Syria and really tackled huge questions about geopolitics, families, and gender. The other film that I thought was beneath the competition was Public Access in that there were so many avenues it could have gone and it was very obvious in terms of the parallels between public broadcasting and today’s social media use, but didn’t really do much besides finding the most titillating aspects of the archive.

JG: There’s nothing more annoying than film critics jumping up and down saying, “This is what the film should be.”

PM: Oh, I agree!

JG: That is not what either of us is saying. They are missing opportunities within the context of the film that they’ve actually made to take it on face value and they miss out.

PM: Public Access showed how, if you give people a forum to democratize the media, they’re just going to whip their dicks out and get naked and do obscene things and we all tune in. There’s so much you could have done with that, bit it gets stuck in the archive.

JG: To go back to Hanging by a Wire, I want to believe that the filmmakers knew exactly what they were doing when they showcased that thing hanging empty at the end as being the metaphor for the political norm of living within this incredibly complicated nation for very specific colonial and internal and religious and sociopolitical reasons. The one visual is more interesting and provocative outside of what the film is actually saying out loud.

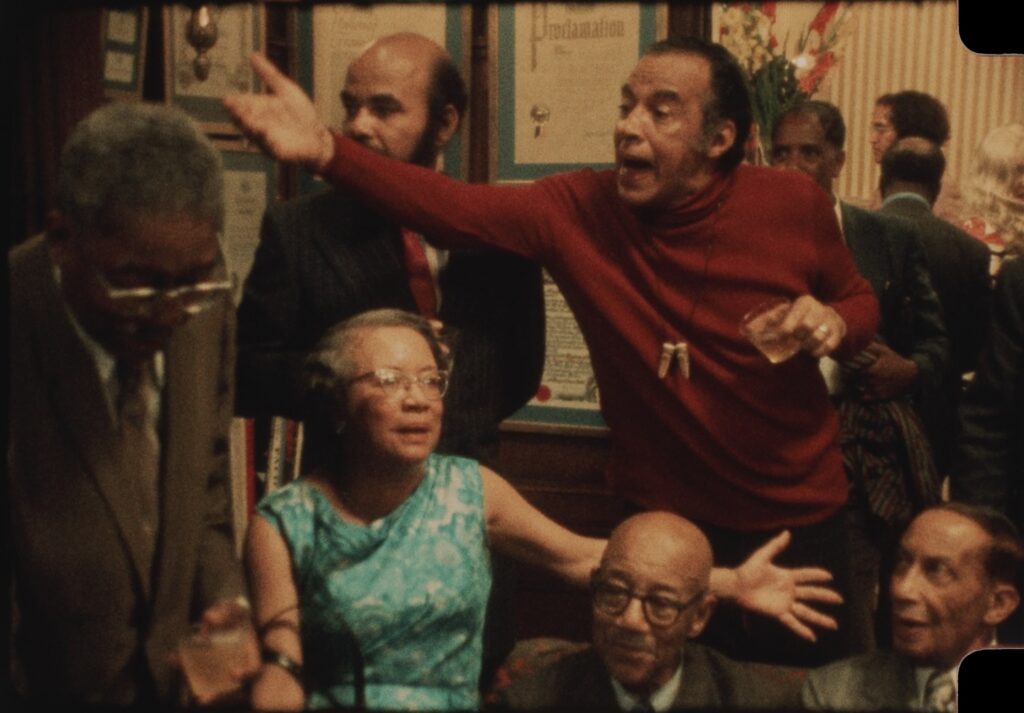

Now one film that’s not a surprise, but is glorious, is Once Upon a Time in Harlem. If it would’ve come out in 1972, it would have been not only forgotten, but it wouldn’t have had impact, it wouldn’t have been appreciated, but more importantly, I’m not sure it would do what it does now. That film needed half a century to digest, it needed us to be able to reflect back on what was to happen to the people in the film after the making of the film, about what would happen to New York City through the 1970s, about what would happen to Black community. When you see New York, not as it was in 1972, but that 1972 New York by today’s standards—the graffiti, the kids on the street, while these beautifully dressed people are having this elite conversation—these are interesting contradictions then. Maybe they’re fascinating now.

PM: That point really hits home around the middle of the film when someone at the party takes a moment to acknowledge how important it is that William Greaves is shooting it. Then it took 50 years for it to see the light of day. That says so much about the larger politics in which the film and all artists and cultural types found themselves in the institutions they were working within and against. I was so worried it would be like The Other Side of the Wind and we’re like, “We waited for this?” Although what does it say if one of the best films at a 2026 festival was shot in 1972?

JG: But that’s it. I will argue for that this is not the film from 1972. This is a 2026 film. The crafting of this footage now works in the same way that Summer of Soul coming out at the same time as Woodstock would not be as impactful. It would have been dwarfed by the very festival that dwarfed it at the time. What made Summer of Soul amazing was the sense of reflection. This film doesn’t have anybody going back and doing the reflection, but these are people reflecting themselves back on a half century before. So it’s this double sense of non-nostalgic analysis of how the past is shaping the present.

PM: I would love to know what the paper edit for Once Upon a Time in Harlem was in 1972 compared to the scenes they selected now. In terms of editing, a couple of films used that approach spectacularly, like Time and Water from Sara Dosa who did Fire of Love. For me, that was easily a standout. It’s a really different dynamic with the archives. It doesn’t have the same immediate wow factor of volcanoes exploding. But it’s about the death of glaciers and the memory that’s housed within layers of ice, and it reflects upon how generations of family are melting away. There’s an interplay between the subject’s family archive and the footage his grandparents shot while exploring glaciers. It’s a thoughtful film and kind of haunting. It was definitely the most fun to write about, which is the best compliment I can give a film.

JG: There are people doing really amazing stuff with archival work, for sure. Some of these filmmakers are finding a hyper textual way of drawing stuff in and finding connections. I get your point about boomer music docs, and a tedious archive doc is also really egregious. But for me, bad movies are bad movies and good movies are good movies and whatever the film is, subject is or form, there can be a good version of that. A mediocre talking heads documentary bothers me much less than a mediocre poetic documentary. Doing poetry badly is worse than doing prose badly. There are a lot of these films that we see, the ones that didn’t get into Sundance—

PM: —the Tribeca premieres—

JG: —that are versions of these structured ways of doing nonfiction. Is there anything worse than the completely poetic film, which is meandering and useless?

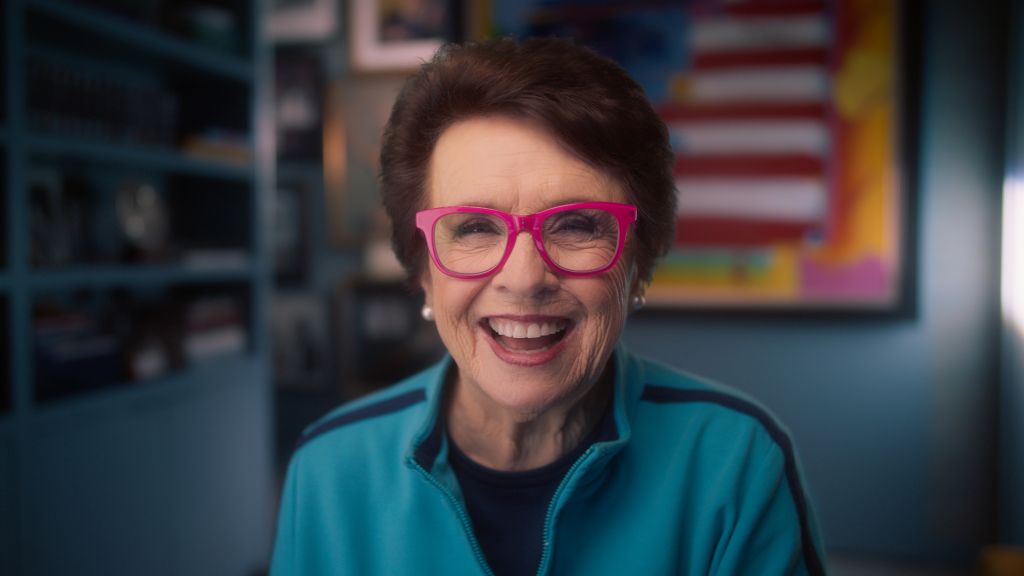

PM: It was interesting to see Sundance have two ESPN docs in the Premieres section: Give Me the Ball about Billie Jean King, by Liz Garbus and Elizabeth Wolff, then The Brittany Griner Story. For the Billie Jean King, we’ve al seen this story before in Battle of the Sexes with Emma Stone and Steve Carrell, but she’s such a great character and is a really good presence and interviewee, has a lot of history to talk to, and both these films are driven by a master interview with the subject. The Billie Jean King one raises all these questions about gender equity, LGBTQ rights and what she was fighting for on the court.

The Brittney Griner has so much potential with this story about her arrest in Russia, the complications of being in a Russian prison, her own fight for LGBTQ representation in pro sports, and her relationship with her wife, but it just doesn’t have the same perspective even though it hits so many similar beats. It doesn’t have anywhere near as much material to work with, and you feel that. One film is like a really bouncy ball. The other one’s just…deflated.

JG: Forget sports docs, but some of the greatest documentaries ever came out of the original 30 for 30 series.

PM: We talked a bit before about the Oscars at the beginning of the conversation, and all five nominees this year are Sundance premieres: Come See Me in the Good Light, The Alabama Solution, Cutting through Rocks, Mr. Nobody Against Putin, and The Perfect Neighbor. Do you think we have any future nominees from this year’s Sundance?

JG: I think always the majority of nonfiction films up for Oscars start at Sundance. These are the films that we’re having in the conversation. In a funny way, the way that Cannes has re-established itself as such a dominant cultural force in terms of dramas, Sundance remains by far the most important for documentary, which to your earlier point, the fact that a lesser film is taking a competition spot matters. One would hope that given the fact that they have such incredible prestige and they’re clearly getting thousands of the best films being made, and with these very limited spots, one would hope that the top of the top the top is what we get to see. But I think we saw some pretty damn good movies. We saw Nuisance Bear.

PM: Nuisance Bear has entered the chat!

JG: This is one of those incredibly rare cases where I’ve known about the project ahead of time because I had the opportunity to give the short a jury award at Saguenay, and I normally don’t watch documentary shorts, Oscars or otherwise, but it was so clearly and extraordinarily well done. In a weird way, despite the fact that I had hope it would be good, I was even more concerned that, being one of the people who did see and champion the short, that we’re just going to get more of the same. And yet the films work so beautifully together. They’re totally different movies, and yet one led me entirely to appreciate the second one in deep, deep and profound ways. It is a glorious film and one of absolutely the most impactful things that I saw for sure this year. But more importantly, it actually asks complicated questions and allows us as an audience the space to come to terms with them. Amazing.

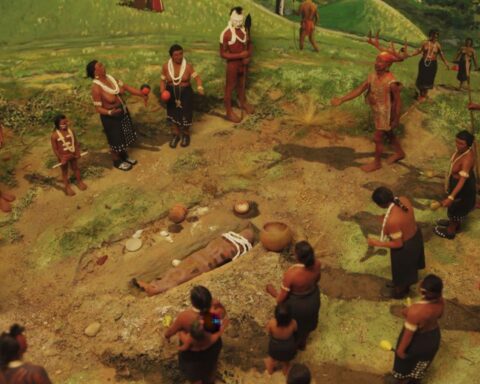

PM: It was the best. The short can stand on its own right, but the way they elevated the storytelling here by bringing in the colonial history, tying it in with the human characters, and looking at people who’ve been driven off the land and the larger politics that are reflected in what the bear’s seeing was brilliantly told. Even stylistically, the cinematography, the editing, and the music from White Lotus guy, Cristóbal Tapia de Veer, gave it a sense of humour that you don’t see a lot in documentaries. It could have gone sideways, but everything clicked and the approach drew you in even more.

JG: This, unfortunately, was not one over devilled eggs at the whiskey bar on Main Street, this was a Zoom interview, but to speak with the two filmmakers the day after they eloped and got married at the Egyptian—he proposed to her the day after the screening, they got married that night, spent a honeymoon day on the day that was supposed to be our interview, and the next day I had a 45 minute conversation with them—we spent an inordinate amount of time talking about how it was only because of the [writers’ and actors’] strike that they were able to use such cinematic cameras because they weren’t being used to shoot whatever the newest X-Men movie was in Vancouver.

It’s the right place, the right time, telling the right film that took a decade for them to put together. And it is so beautifully done. My favourite thing is a film that should be terrible, and my favourite film brings that sensation of, “They’re just about to screw this up,” and then it turns something glorious. This film joins the pantheon of films that go way beyond their form, way beyond their content, and become something truly transcendent.

PM: Speaking of Canadians in shorts, Ben Proudfoot won the Grand Jury Prize for The Baddest Speech Writer of All, and I think he could be looking at Oscar number three. I still like Last Repair Shop best, but it’s certainly worthy of attention again for this work with Stephen Curry. And what a great character with a Martin Luther King Jr.’s speechwriter and lawyer Clarence B. Jones, who’s taking us through all these stories, and they really riff throughout the movie. They make jazz. The shorts always get lost, but there were some really great ones, like the Luigi Mangione, which one was a lot of fun.

JG: We talked about the $12 million Boys State sale, which is absolutely amazing, but a lot of it was that the streamers couldn’t buy the big drama films, so they would throw their weight around and buy documentaries. That certainly reduced by 2019, at least. Shorts have never really had that impact financially within the system. We talk about finance because Sundance became this incubation of purchases even more so than of films. So there’s a purity to the kind of short film showcase at a place like Sundance. And you get somebody like Proudfoot who has just been kicking it for years doing incredible work within this relatively non-commercial way of making films that are the big ones that we’re talking about when it comes time to the end-of-the-year lists when we’re talking about all the features.

PM: On the business front, they had a virtual panel during the festival. It had Ryan White, who did Come See Me in the Good Light, and Geeta Gandbhir who did The Perfect Neighbor, as well as RJ Cutler who did the Billie Eilish documentary, and there were a couple of salespeople and agents. They were talking about the business of Sundance because Ryan and Geeta had the two big hits from last year’s festival. I was surprised that nobody seemed too worried. They’re kind of like, “Well, it’s always waves.” They said the number of buyers is down, but that if Netflix is still out there getting films like The Perfect Neighbor, they know that people are watching. If you know how to look at it and know that the buyers are looking and whatnot, we can be hopeful that great films will find a market. Gandbhir talked about The Perfect Neighbor being a “Trojan horse” because it could get pegged as true crime to draw viewers, but it wasn’t that at all. But at the same time, Ryan White was saying that for a few years he and his producing partner had a load of stuff, and then other people weren’t getting anything. That point’s similar here.

JG: That’s a much, much longer conversation about whether stuff a theatrical run or works better on small screen. Come See Me in the Good Light being a really good example of something that obviously benefits enormously from being seen with a community in a theatre of a bunch of weeping people—

PM: —or people laughing.

JG: Exactly. On the one hand, I love that these filmmakers are making enough money to encourage them to do other things. On the other hand, oftentimes I am with theatrical runs. I love that anybody all over the world can watch these films on a moment’s notice, and it makes me kind of sad that they’re not getting theatrical runs.

PM: None of the Sundance docs has announced a sale yet, so if you were putting on your buyer’s hat or sales agent’s hat, what do you think should be looked at in terms of distribution potential?

JG: A24 already has Nuisance Bear, but it’s still up for sale. So there’s a good example: A24 gave them money to make it, but doesn’t necessarily have the rights for theatrical, etc. It gets very complicated with that. It will be interesting to see how something like Cookie Queens gets responded to. I would love to see that get showcased in a bigger way. Same with All about the Money. The last title card talked about how the subject wanted to buy the film so that it would be buried, but of course it’s one of those things. This is a subject who says a bunch of stuff and doesn’t do it. What do you think going to get attention?

PM: Nuisance Bear is the obvious one. And then Soul Patrol. It’s about Black soldiers in a special ops unit in Vietnam. Great archival footage and brilliant re-enactments that create, again, really elevated storytelling. And then maybe for potential sales movies, the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize winner To Hold a Mountain, but I think that’s more of a festival movie. It’s a really strong feminist environmental film and has just a great salt-of-the-earth, pastoral cinematography, lots of cats. It’ll play well with people, but I think it’s a tough sell.

JG: One of the challenges of that type of film is that people want political docs, but they want political docs from particular perspectives about particular regions.

PM: One of the stronger films at Sundance was American Doctor about doctors volunteering in Gaza, and that was the feature directorial debut of Poh Si Ten, who’s pretty well connected in the documentary space, but I worry about the film because it wears its politics on its sleeve. That’s tough in this climate.

JG: I think we’re all looking for a film that will teach us about something. Even if we agree with it, shows it in a different light. For example, AI is everywhere, and while it may be too esoteric and cerebral, Ghost in the Machine is actually really strong. It is a fascinating examination that probes pretty deeply into the philosophical depths of AI. It obviously speaks to me as somebody who’s interested in technology and this background in philosophy. I don’t expect this to go wide, but I think that there are some people that will actually recognize the core tenet of fascism that fits very nicely into the techno futurism.

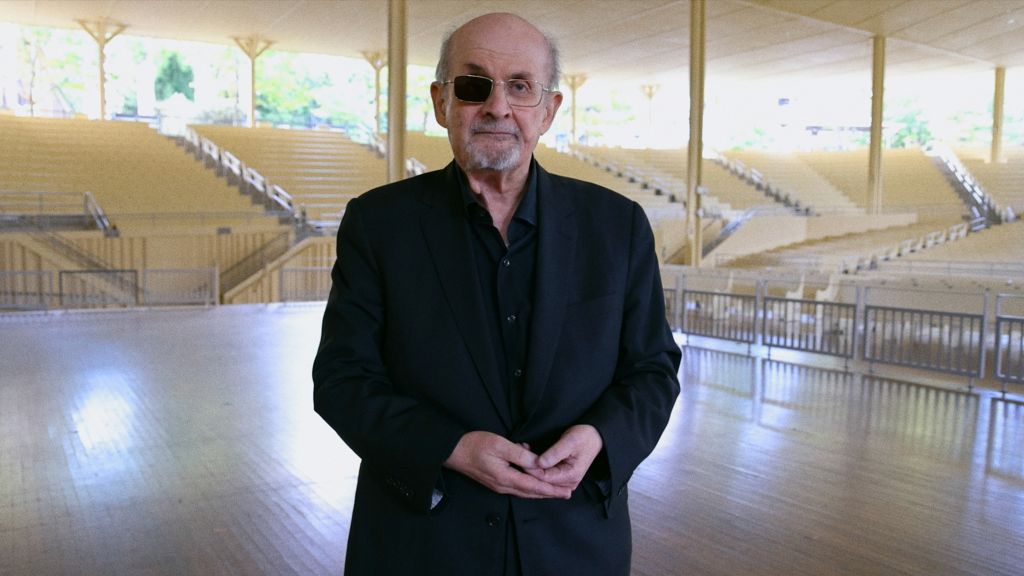

Then let’s talk about the films that we didn’t see and didn’t play the online festival. The Salman Rushdie film being an obvious example of something that I wish I would’ve seen and there was no virtual opportunity.

PM: And the AI documentary by Daniel Roher and Charlie Tyrell.

JG: History of Concrete, which looks amazing. These are films that I desperately want to see was unable to.

PM: The Salman Rushdie got a fair bit of coverage, but I don’t think I read anything about the AI documentary. I heard nothing, and that’s a shame. One producer who I’m friends with on Facebook made a post that she overheard someone at Sundance, a filmmaker with a film in the selection, say that he didn’t want many people to see his film there. It was causing a lot of debate about the fetishization of feature documentary, but also the politics of programming. If you’re in it just for the laurels, why are you at the festival? How many good films have you seen that had embargoes up the wazoo, and then just died because nobody talked about them?

JG: There was always a baked-in hustle at Sundance. Traditionally and habitually, Sundance has been where people take chances, where there’s an entrepreneurial notion of what’s taking place in the filmmaking: aesthetically what drives better films, not better product. The art itself is outward looking. The reason some films birth at Sundance and then go on to be the ones that we talk about a year later is because they truly are looking in a deeper, more profound way at the audience than are many similar films from different regions where the quality of the film is secondary to a particular funding mandate or a particular subject. May Sundance be a place where people look to bring films to share with the world, but to get their start at this extraordinary little winter film festival!

PM: One of the better films in the U.S. competition was Barbara Forever about Barbara Hammer, the experimental filmmaker who really pushed boundaries for lesbian visibility and onscreen representation. It repurposed her archives brilliantly, but the climax of the film is her getting a movie into Sundance and what that meant in terms of attaining that level in her career. But then it was a great year for queer representation and lesbian representation comparatively at the festival. She had her camera around at all the screenings and was talking about what it meant to be there at that moment. It was fun to see the politics and institution of Sundance come together in the narrative arc of one of the better films at the fest.

JG: When it comes to nonfiction, if you’re even tangentially a fan of the form, this truly is the birthplace for some of the great documentaries ever made. It cannot be over-emphasized. If we talk about the great film festivals ever in the history of this medium, Sundance by far is the locus for nonfiction at its peak, and it continues to plow that. The Sundance-y drama has other outlets these days or challenges within the marketplace, but whatever happens, Sundance is a documentary film festival that happens to play some dramas. There can be three or four drama films that pique interest, but there are often a dozen works of nonfiction that are the ones that we’re talking about not only this, but in years to come. And so long may it run.