The auditorium was packed, the atmosphere tense. The occasion was a panel on censorship at the Canadian Images Film Festival, which took place after the screening of several short works, including a sexually explicit piece by Barbara Hammer. The film, like many of her earliest works, featured the filmmaker herself.

The event took place in 1983 at Trent University just as the so-called sex wars were about to create a deep schism between antipornography feminists like myself and those who called themselves pro-sex. I was on the frontlines of that debate, already alienating small-l liberals and filmmakers and artists who were hostile to the argument that absolutist free speech points of view might operate against the interests of women.

I don’t remember the title of Hammer’s film or who presented the anti-censorship position that day. I do recall that I was unbending in my belief, as was most of the audience, including my anti-censorship antagonist on the panel. When it came time for Hammer to speak third, she sat silent for several seconds and deadpanned, “I don’t know. I’m just recovering from seeing my vulva on a huge screen.” It was a candid response that cut through the two opposing arguments to give weight to both sides. Yes, she did feel vulnerable as the subject of a sex film and the viewers’ collective gaze, but she was determined to author her own sexual works as a path to empowerment and lesbian visibility.

For her entire career, right up until she died in 2019, Hammer put herself on cinema’s frontlines, fearlessly facing that vulnerability, whether offering audiences a full view of her genitalia or coping with her 2006 cancer diagnosis. She began making art with a visceral urge to blur the edges between her private and public life; it was a conscious choice, which never diminished. Asked by Vanity Fair to articulate her thoughts on the gap between one’s private and public self shortly before her death, she declared, “Make them as small as possible. Try to avoid having any.”

Hammer began making movies in earnest in the early ’70s, when there was no internet, no female webcam wonders and the pornography industry was a multi-million-dollar business owned by men controlling women, using them and selling a warped version of (hetero)sexuality for massive profit.

On her own and almost entirely without an underpinning ideology, Hammer hit upon a solution to the conundrum many feminist artists were trying to resolve: how a woman might appear in a sexually explicit film in a way that maintains her power and does not cave to the male gaze. The answer? Women had to make their own movies. But that was just a start. More importantly, to upend the power imbalance between director and subject, female directors had to appear in the films themselves.

Women artists and activists were inspired by the strategy and many of them attempted to emulate Hammer’s method. One Toronto project funded women to make their own films with sexual themes (although not necessarily explicit), creating a fascinating 1983 program including works by Lisa Steele, Lynne Fernie, and the late queer activist Chris Bearchell.

By the time she died, Hammer had made nearly 100 films, and had become not only a lesbian icon—probably the first artist to have achieved mainstream acclaim for a lifetime of work done as a lesbian, largely about lesbians—but also a revered artist worldwide, with a MoMA retrospective and an exit interview (as she was dying of cancer) in The New Yorker. A lesbian experimental filmmaking grant has been created in her name, Hammer’s archives now sit in Yale’s Beinecke library, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science plans to restore more than 80 of her films.

Hammer always had her ties to the world of cinema, She was born in Hollywood in 1939, the granddaughter of D.W. Griffiths’ cook, but, though she made her small film Schizy in 1968, she did not attend film school at Sonoma State in San Francisco until 1973. There, she developed a slow burn of outrage at the absence of films made by women, let alone queers, though she was shown a film by avant garde artist Maya Deren, to whom she paid tribute in her 2011 film Maya Deren’s Sink. Her college experience inspired her mission to remedy the sad cinematic situation by making films about lesbians. Her early works included 13 experimental films documenting her own life, relationships and community. They were experimental and challenging, yes, but they were also playful, pursuing the idea that being a lesbian is fun, and, herself happily promiscuous, openly celebratory of non-monogamy.

By boldly inscribing herself in the work, Hammer also gave new meaning to the term autobiographical documentary, a genre of film quite distinct from cinema verité, which looks inward instead of outward and revels in subjectivity rather than a neutral stance. Don’t confuse it with works by Morgan (“Look what I did!”) Spurlock and Michael (“Aren’t I funny?”) Moore, who also inserted themselves into their documentaries. While they have made important movies—Moore continues to make documentaries that speak out against the current American president in ways that matter—neither takes serious formal and personal risks. Think more of Ed Pincus’s Diaries: 1971-76, in which he documents aspects of his personal life, including his open marriage.

But though Pincus’s movie was transformative when it comes to the documentary genre, it was Hammer who decided to make herself the centrepiece of sexually explicit films, challenging and subverting heteronormative sexual representations. You would think someone outraged by the dearth of women filmmakers might tiptoe into the field with something a little less outside-the-box. But Hammer was always interested in sex on some level. The first time she went to San Francisco’s Gay Pride parade in the late ’70s, she went with a recorder to tape people’s descriptions of their orgasms.

Her 1974 film Dyketactics is considered the first lesbian lovemaking film. It is four minutes of joyful lesbian cavorting and sex, a kind of Woodstock for lesbians without the music (they wash each other’s hair) against the backdrop of a woman spreading her legs, revealing her vulva. It is bold, like nothing anybody had ever made, and, crucially, not even remotely interested in the male gaze or any pornographic aspirations. It is experimental, backed by electronic music, and featuring images layered on top of one another, a four-minute whoosh of non-narrative delights. In a rush, other pioneering titles were created: Sisters! (1973), Menses (1974), Superdyke (1975), and Women I Love (1976).

This early era of her groundbreaking lesbian filmmaking peaked with Double Strength (1978). It features Hammer and trapeze artist Terry Sendgraff in a performance piece designed to present the arc of their relationship while showcasing their physical muscle. In her autobiography Hammer!, the filmmaker insists there was nothing gratuitous about the project, saying that she had no choice but to feature the two of them in the nude because there existed no outfits that adequately revealed their muscles.

The vast majority of us do not make the choice to pose naked in pictures for public consumption or record our lovemaking for an audience. Many feel it’s an invasion of privacy. You could argue that such a reaction is fundamentally repressed and that we’re a product of a puritanical social construct, but, regardless, or even accepting that, we usually don’t overcome it.

But though she did, in Peterborough, feel vulnerable in the moment she saw her vulva on screen, Hammer ultimately felt that the empowering aspects of what she was doing far outweighed her personal discomfort.

And she was empowering an entire community in the process. I’m not referring to films like Women’s Rites in which she shot women dancing joyously at one of the first ever Lesbian Conferences in 1974 or, Superdyke, in which an army of Amazon (the ancient, good kind) warriors invade City Hall and Macy’s while trying to conquer San Francisco. Rather, I’m thinking of early films like Dyketactics and Menses, about the power of menstruation, which present naked women loving each other and their bodies, and in large groups.

In Dyketactics, that cinematic reverie on lesbian lovemaking, Hammer’s subjects almost never look at the camera. They’re too busy to worry about an audience. Astonishingly, Dyketactics subverts the male gaze even before Laura Mulvey coined the term in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Visually creative, consistently overlaying images, sometimes working with paint or negative reversals, juxtaposing things like human lovemaking with erotic rock formations, playing with sound—in Pearl Dive, two women repeat “I Love You” under water—and eschewing linear narrative, Hammer’s work is the ultimate antidote to mainstream pornography, which features a single narrative leading to the infamous money shot of a male orgasm.

It’s no coincidence that she was fascinated by touch, believing that it is “the number-one area of sensory perception that we use in all our work.” Her film Place Matter aspires to “touch” nature. To get a sense of her creative ingenuity, consider her photo project Camerawoman, the result of a lecture in which, deploying an instant camera, she went blindfolded into her audience, touched someone, talked about her emotional reaction to the person and about the emotion in the person she was trying to photograph.

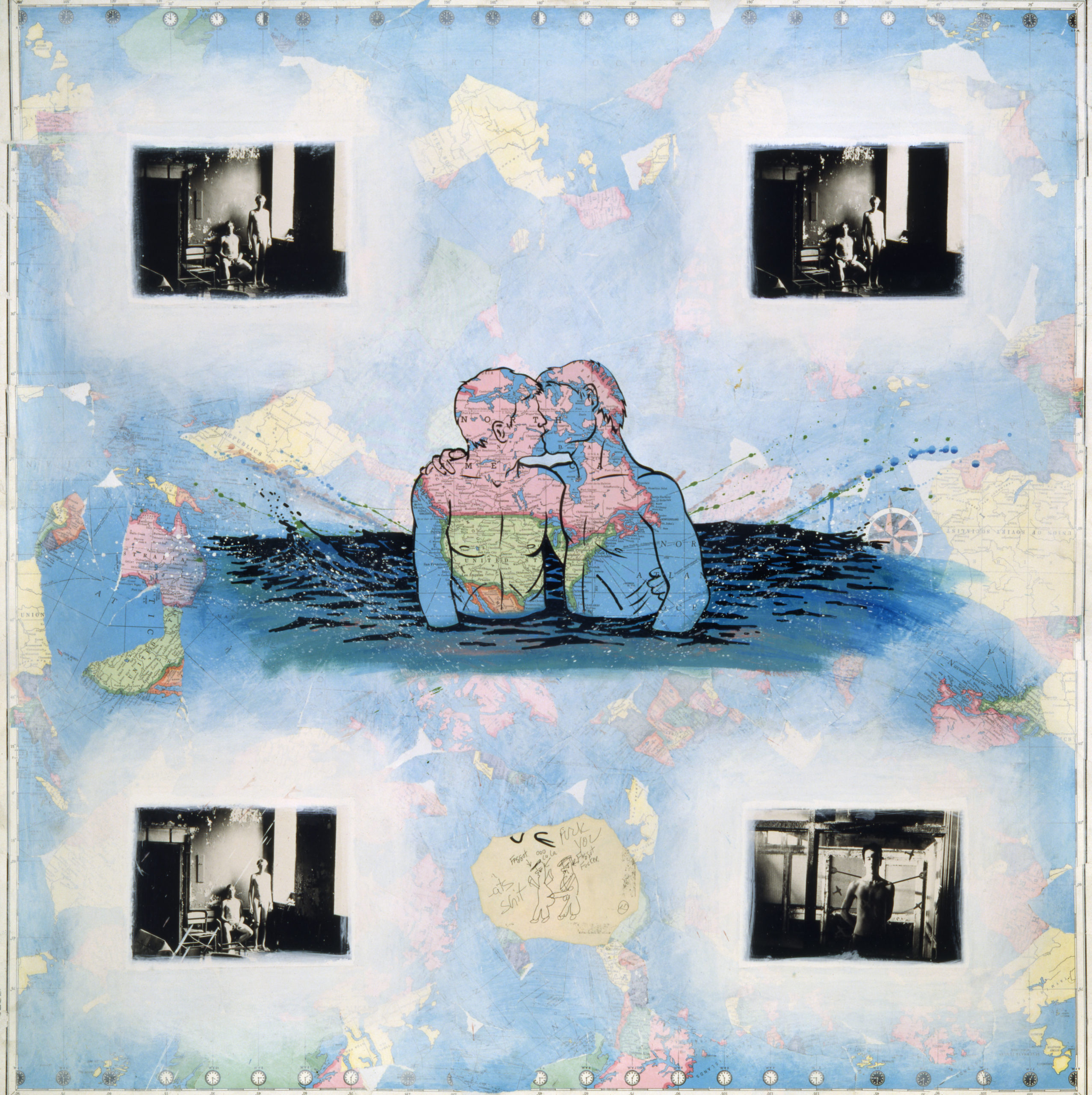

As Hammer pursued her career in the ’80s and ’90s, every film offered a startling visual experiment—she prided herself on never repeating herself artistically—and her work became increasingly assured. She didn’t abandon her sexual interests but she did widen her lens to take on larger, less subjective themes, like the struggle against AIDS and the invisibility of lesbian history. She made movies about Korean women diving for shellfish and about visual artists like Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard, focussing on the work they made during World War II. Her 1990 film Sanctus uses X-ray images to probe ideas about the fragility of the human body.

Seeing the film now, especially when the words cancer and metastasize appear among a series of medical clippings, you feel an intense emotional tug. Hammer was diagnosed in 2006 with stage 3 endometrioid ovarian cancer. But nothing could cloud her artistic vision or weaken her creative force. This isn’t to say that she did not feel pain, anger, or even fear, but she realized early that her medical crisis offered creative possibilities and she seized on them. She had always been interested in probing the aging process, though she started with her grandmother’s and not her own. Her 1985 Optic Nerve manipulates and layers images to document a visit to her grandmother’s nursing home and develops a highly emotional reflection on both family and the vulnerability that accompanies aging.

By 2010, she had recovered from her first cancer but remained deeply attuned to the fact of her own mortality. Via her 30-minute film Generations, the 70-year-old Hammer mentored the younger filmmaker Gina Carducci during a sojourn to Coney Island, where the two managed to film in such a way that the human aging process was reflected in the tired architecture of the amusement park and in the emulsion of the film medium.

She had already made her own illness the centrepiece of one of her most beautiful films, 2009’s A Horse Is not a Metaphor, which tracks her cancer treatment, including X-rays and chemotherapy, in very direct ways. While shooting in hospital, gone are the elaborate experiments and manipulations that characterize most of her work. What does remain is Hammer’s commitment to keeping the work up-close and personal. She presents herself nude and hairless and keeps the camera trained on her body in intense close-up as she receives chemotherapy through her abdomen. With her partner of 30 years, Florrie Burke, at her side, she asks her physician pointed questions and absorbs what is at first bad news calmly, stoically. These sequences are interspersed with scenes, featuring her signature layered style, in which Hammer is seen riding through Georgia O’Keefe’s Ghost Ranch (which is more than unsettling), Wyoming’s Big Horn foothills, and Woodstock, New York, backed by a transcendent score by Meredith Monk. By the end of the film, her health prospects improve and the horseback rides become emblematic of a new kind of liberation.

After her cancer went into remission, Hammer continued to create with a vengeance, calling herself a cancer thriver, not a survivor. But the disease returned and it became clear that her life was coming to an end. That silenced neither her voice nor her creativity. With her death on the horizon, she became a fierce proponent of the right to die and, though she did begin to focus more pointedly on her legacy—taking care to catalogue her art, handing over her personal archive to the Beinecke Library at Yale—she did not stop making movies. Her last retrospective Evidentiary Bodies includes a work which is part film, part performance piece, part installation, and features her CT scans as part of an examination of illness and intimacy in a lesbian life. Months before she died, she gave a lecture at the Whitney Museum entitled “The Art of Dying (or Palliative Artmaking in the Age of Anxiety)” in which she suggests that for her, the only way to relieve the pain was through making art.

When she was asked once to comment on what vulnerability meant to her, she said, “Vulnerability is not a weakness in a computer system, a personal flaw in another, or an exposure to be covered over or protected. Our vulnerability to one another and to ourselves is our strength.”

She was so determined to be public with that vulnerability that she entertained the idea of the ultimate act of public exposure: dying in front of an audience. She had even engaged a gallery to be the site of her death. But she gave up the concept, realizing that the project would wind up compromising the delicate palliative process. That last decision may represent the only time Barbara Hammer ever resisted taking a risk.

Update (04/07/2023): Select films by Barbara Hammer are now available on Tënk.