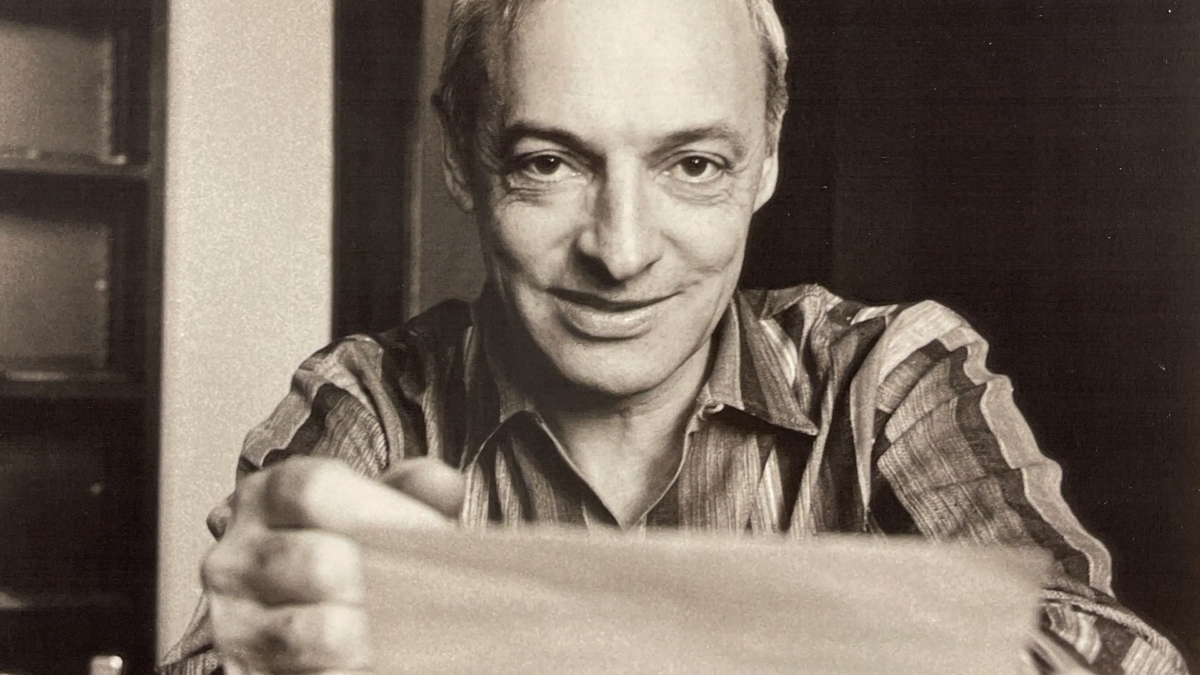

For over a decade, Mark Cousins has provided some of the most ambitious filmmaking regarding the art of cinema itself. His epic The Story of Film: An Odyssey was structured as a 15-espisode television show and saw its theatrical debut at Telluride and Toronto in 2011. He continued his cinematic survey with A Story of Children and Film in 2013, which further solidified his desire to expand the so-called canon to all the corners of the world and drew even more clips from films both familiar and ripe for discovery. His Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema (2019) provided another 14 hour-long journey and further emphasized the exploratory nature of his work, as well as his advocacy to spotlight directors and artists who often have been relegated to the shadows.

Cousins’ latest documentary, The Story of Film: A New Generation is very much is more of the same, with the director bringing viewers up to date with the ten years of output that has occurred since his first odyssey. It confronts, in slightly tangential ways, the lockdown that drove movie-watching further indoors and put public spaces into a kind of sleep. Scheduled to be the first film screened at Cannes prior to the official opener, it’s somewhat surreal to watch this survey of everything from esoteric art projects to brash blockbusters during these ever-evolving times. (At the time of writing, Ontario’s own theatres remain closed to the public after nearly seven months.)

Cousins’ addendum to his overall project will please fans of the Story of Film series, but may frustrate detractors even more. Whatever your response to his laconic narration and scattering of carefully curated clips, it’s clear that his love of movies emanates from every frame. Some selections are inspired and surprising, while others feel at best tangential and others downright redundant. Cousins’ own interspersed contributions collected as part of a global journey are mixed. Yet this time when many have suffered so much, it’s wonderful to be able to welcome something contagious that’s truly good for the soul.

POV spoke with Cousins by Zoom prior to the film’s premiere at Cannes.

POV: Jason Gorber

MC: Mark Cousins

The following has been edited for clarity and concision.

POV: You call this project The Story of Film, not A Story of Film. How much should we read into that?

MC: Not too much. I was influenced by a book called The Story of Art by E. H. Gombrich, written a long time ago. It was partial and left loads of stuff out, but it was a starting point, an invitation to come on an adventure. I like saying to the audience, “I’m a storyteller, let me take your hand for a bit. Then I’ll let you go and you can explore.” Twenty minutes into my work, people realize that it isn’t a heavy-handed single narrative. It’s multiple narratives, and I’m providing a nice starting point.

POV: I can contrast it with the title Scorsese used, A Personal Journey. Inevitably, he was doing something much more autobiographical. Was there ever a consideration, as the project expanded into this behemoth, of making even more overt your own personal taste?

MC: I did make a film called A Story of Children and Film, so I have used that title some times. Yes, a lot of my personal taste is in this. But I would argue that if you look through the history of cinema, the really subjective takes have been by people writing in the English language—dare I say men, and dare I say white men. Their ways, as we know, have been wildly subjective and they left out big chunks of the world and huge types of filmmakers. You could argue that my approach tries to cover different parts of the world and many different forms and styles. In one way, it’s less subjective. The Story of Film is the door on which you knock to get into the house. Once you’re in the house, then, hopefully, there are many rooms to explore.

POV: Let’s talk about your process here. How do you watch the vast majority of your films? Are you watching films these days with a sort of editorial eye and thinking, “Oh, there’s a clip that’s going to work really well in my next documentary?”

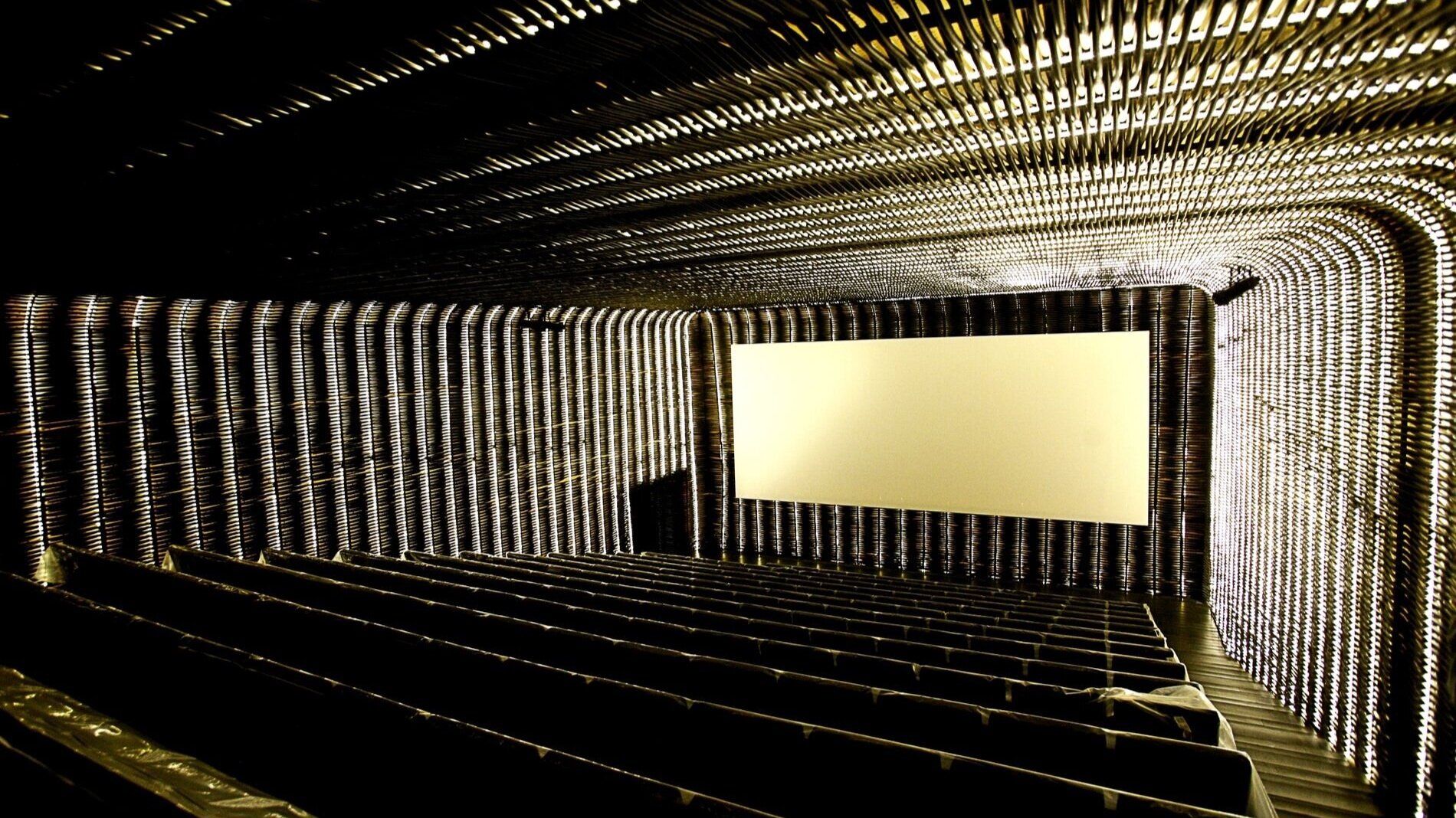

MC: [Laughs] No, I still watch films the way I always did, in the front row of the cinema, with my guard down, without any filters, like a child. I watch like the boy that I was when I fell in love with cinema. I’ve got a good visual memory, so I don’t take notes. If I’m working on a film that is about cinema – and lots of my films aren’t – then I will take notes. Being a filmmaker and seeing behind the curtain hasn’t taken away the sense of wonder about filmmaking or about going to the movies because it’s still bigger than life.

POV: Are you still seeing primarily films on a big screen or have you set up a ridiculous home theater?

MC: Nope, no ridiculous home theater at all! I go to the cinema every day if I can. Local theatres are open here in Edinburgh, so still seem films on the big screen where possible.

POV: Your film is the pre-opener for Cannes, and they’ve shaped the premiere as a way of getting us back into cinema and as a reminder of what we’ve gone through over the last year. But I think the film’s more subtle than that. It’s a look at the last decade from your initial project, how you have reshaped the project, but it’s also about the collision between blockbuster spectacle and the overlooked international elements, and something like an Oscar winner can also be an art house masterpiece.

MC: The last decade of cinema is harder to categorize in some ways than some of the previous decades. More people from more parts of the world, and in turn more different types of people, are making movies than ever before. You and I know, there was never a single narrative to the story of film—it was never mainstream versus edge. The river always had multiple channels, but now we’re into a wide delta. Films are happening in so many ways in so many places and that process needs to continue. It’s a multiverse—that’s why I love Spider Man: Into the Spider-Verse, and that’s why the last clip in this film is from that film. When you go into the cinema today and seek out all sorts of films, you don’t not know which realm you’re going to enter. And that’s fantastic!

POV: One obnoxious current of film criticism suggests that, when a film wins an Oscar, it somehow becomes diminished by its popularity, which is the flipside of the anti-subtitle crowd. How do you navigate this broad canon?

MC: There’s a lot of snobbery, unfortunately, and particularly in middle-class culture, liberal culture, and bourgeois culture. “I’ve found the best coffee shop!” or “I’ve found the best place to get croissants and you haven’t!” I come from a working-class background – there are lots of problems with working-class backgrounds, but that ethos is not one of them. We aren’t interested in the word “exclusive.” When it comes to cinema, I don’t get the people who think, “Oh, because I’m into Ozu and because I’m into Kore-eda, or whomever, then Kore-eda is now a sell-out when making a more mainstream film in English.” We need to be category-blind, in some ways, to remove ourselves of generic expectations and class expectations. We need to avoid those pitfalls, that minefield, because it really skewers our sense of pleasure. We lose out of we’re approaching cinema through too narrow a lens.

POV: Can you think of a film, in the entire project, that you personally despise and yet still included because you thought it was important to the story of film?

MC: Not really. The opening film in this one is Joker and I had many complex reactions to it. I was thrilled and excited and disgusted at the same time. That film was like a cattle prod. It was like being hit by lightning, and it’s there for that reason. If I really hate a film, I usually walk after about 30 minutes, or I wipe it from my memory banks. Occasionally I’ll hate a film and I won’t wipe it from my memory banks, like Phantom Thread. I know all the critics loved it, but I really didn’t like it, and yet somehow it stuck with me. But mostly when I have the feeling of despising a film, I put it straight in the trash can and hopefully I’m rid of it.

POV: This project has some of my favourite films from the last decade, like Mad Max: Fury Road, Act of Killing / Look of Silence, and Baby Driver. Then you have three films that I am still aggrieved by. I was at the Cemetery of Splendour press premiere at Cannes where the entire row was snoring and then leapt to give it an ovation at the end. I hated Goodbye to Language with a burning fiery rage, and Leviathan was equally execrable. What is your reaction to the people who come up to you and say “Oh my God, I love this film!” and “Oh my God, I hate this film!”? How do other people’s views engage with your own project?

MC: I get a lot of people telling me that they love a film, but I don’t hear the hate very much. I think there should be real amplitude to our reaction to the world in general and to cinema. If everything’s just sort of a slightly undulating wave, that doesn’t actually capture what it’s like to be alive. To be alive is ferocious! When we’re at the top of the storm and we’re down in the belly of the beast the amplitude is great. Therefore I’m not surprised that there are really strong feelings about films. Yet I certainly have no inclination to debate with you about Cemetery of Splendour because you had your reaction and I had mine, and there’s nothing to be gained in that.

POV: We might have been sitting beside each other if you saw it at Cannes, because I’m also a front row kind of person.

MC: Quite possibly. Life’s too short to try to persuade other human beings by raining on their parade. That is not my bailiwick.

POV: At a fundamental level, do you see this project as a celebration of cinema?

MC: Celebration doesn’t feel right. I see it as a film. I’m a filmmaker and not a critic.

POV: I’m going to push back slightly because you say you’re not a critic. You liberally use words like “masterpiece” in your voiceover. Your critical response overtly comes into your work.

MC: Lots of my mates say something’s a masterpiece, but they’re not critics. Your previous question suggested everybody’s got strong opinions, whether they’re critics or not. But I don’t have a job reviewing films, for example. I don’t go to press screenings. I spend my time trying to work out how to make a film, and sometimes I use film clips as my material, and sometimes not.

POV: What’s the first movie you saw that made you love cinema?

MC: The first movie I saw that made me love cinema was the first movie that I saw in the cinema, full-stop. It was Herbie Rides Again. I don’t know what age I would have been, but I remember the feeling of flying. That was in the theatre, but before that, the Troubles were on in Northern Ireland, so it wasn’t easy to go to the cinema. I saw lots of films on TV. Tilda Swinton and I did something called the “8 ½ Foundation” because we reckoned we both fell in love with movies at the age of eight and a half.

For me, it was TV late at night, particularly horror movies, or “video nasties” as they were called in the 1980s: Evil Dead, stuff like that. After loads of horror movies, I saw Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho on TV and I could tell it was a different kind of animal. It was scary, but it had a rise and fall. It had a climax and then it took your heartbeat right down to almost zero again and moved at a snail’s pace. I was nine, and there was a real sense of being moved through the movie experience by somebody who really knew what they were doing. Then, in rapid succession, I saw Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil and that was life-changing for me—you could watch a film and have no clue what it was about. I had no idea that it was about sex and race! It enveloped me like a blanket. That’s where the magic happens, with the mystery of falling in love with something you don’t understand.

POV: What was the first documentary you saw that made you think, “I could do this?”

MC: It took a while for me to realize that. I started directing around 1989, but at first I wasn’t very good. I’d seen lots of documentaries by that point. A documentary that really sticks in my head from early days was Maximilian Schell’s documentary about Marlene Dietrich [Marlene, 1984]. Did you ever see that one?

POV: No. I’m a huge Black Hole fan, but that’s another story.

MC: Dietrich agreed to do an interview with him. She was in her 80s at that point, so he brought his cameras to her apartment in Paris and she said, “What are the cameras doing here?” He said “Well, you agreed to do an interview” and she said “not on camera!” So he thought, “Holy fuck, what am I going to do?” He did an audio interview and then recreated her apartment in a studio and had the camera drift through the empty apartment. We hear her voice, and we see her apartment. It’s like she’s a phantom gliding through her own apartment. It’s mesmerizing. Not only is it a great documentary, but also teaches you something about the unseen and the power of not seeing her as an old lady. She didn’t want to be seen as an 80-year-old, but it’s unforgettable because it doesn’t complete your desire. It leaves you wanting something, which is the image of her and that’s the thing you don’t get.

POV: We talk a lot these days about what counts as a film, with much nonsense about whether Lynch’s latest Twin Peaks is a film. You include Lemonade (a music video) and 13th (a streamer documentary). And here we are with your film playing at Cannes, which has been very vocal about what counts as cinema or not.

MC: My film’s not for TV. There’s no TV money of any sort in it.

POV: But how do you delineate what gets included in The Story of Film? You’re not including, say, HBO series like The Wire or Deadwood.

MC: I don’t put loads of American stuff in there because I want to cover the world, that’s first.

POV: But you do include Black Mirror, for example.

MC: I like The Wire very much, but one of the things the pacing does is to try to keep you watching. It’s something slightly different. It’s sort of assuming that you could pause and put on the kettle or eat a pizza or something. I love the movies – the television and, of course, cinema – which is paced somewhat differently. Dare I say, it almost has an arrogance about it, something that will use shots and cuts so confidently. It’ll assume that it has hypnotized me and I can’t look away. As you acknowledge, you can’t clearly separate these things. But for me, I particularly like the things that are using shots and cuts in a slightly mesmerizing or intense way. There’s something slightly casual about the way that we watch TV, or certainly about the way I watch TV. I usually have my phone in my hand.

POV: Is that one of the reasons you actually go to the cinema, so that you can actually be cloistered?

MC: Absolutely. For me, it’s not so much about the story, it’s about the fact that I say to the director, “Here’s two hours of my time. Do something wise with it, I trust you.” If you don’t use my two hours wisely, the next time you make a film, I might not buy a ticket. But if you do use it wisely, I’ll be front of the line next time.

POV: How does the process work for assembling these clips?

MC: It’s all fair use. I usually don’t take notes, but I usually remember a scene from a film that stands out for me. That just goes into the old memory bank. When it comes to actually making the film. I do this [he holds up to the web camera a series of cue cards with scrawled handwriting]. It says Story of Film: Updates, so it wasn’t called The New Generation at that point, and then on each piece of paper, I will write either a clip, the name of a clip, or a piece of music or a theme. This one says “Gaspar Noé, Climax.” In fact I didn’t use that scene! [He shuffles through the cards.] This one says “Lemonade,” and I did use that scene. [He shuffles again and picks one from the middle.] This says “Joker,” and I look where Joker was! It was originally about twenty minutes in, but I took it out and put it right into the front. The front card already said “Frozen.”

That’s the way I work. It’s very free, cheap, and simple, but it’s also a very good way of structuring a film. I start with that, and I move to this kind of thing [holds up a taped-together series of paper sheets.] This has the running order and my scribbles. Once you’ve got all of that, we have the structure roughly in place, and then I start to look at the clips. I always write in the present tense, so I’m looking at a clip and writing about what I see without pausing—really fast if possible. That’s so it doesn’t feel like I sat and wrote something and then looked for a film clip to illustrate it, because that doesn’t work for me. I like to feel that it’s more present than that.

POV: And how are you getting the clips themselves? Are you actually ripping Blu-rays?

MC: Yes. I have a great producer, John Archer, at Hopscotch Films in Glasgow. I’ve worked with him for a long time, and they provide the Blus and rip them.

POV: Have you had any films in a cut that you’ve been asked to remove?

MC: No.

POV: You’ve never had people come back and suggest that the inclusion of a film was not appropriate?

MC: No, because when we complete a film, we pass it by fair use/ fair dealing lawyers in L.A. and in London or Scotland. I’ve probably used fair use/fair dealing more than any filmmaker in the world. It’s all legal and all signed off because we have to get insurance on all of these films, and you can’t get insurance unless a lawyer will say it’s all kosher. I can only use a small amount of the film, so there’s never been an instance where I’ve been prevented from using a film—total creative liberty.

POV: I think it’s fair to say that we both love film the same way, even though we love different films. Have you found it to be as contagious as you would like it to be, or are you more cynical?

MC: I’m not more cynical, to be honest. My films have seemed to have had a positive effect. When I made The Story of Film: An Odyssey ten years ago, I’d no idea what it would become. I didn’t even think it was very good! We didn’t know that it would be sold around the world and it has. It’s changed film courses and the way film is taught, from China to America to South America to across Europe. It’s also influenced the sort of films that are being restored by film archives, etc. It’s had a substantial influence, much to my amazement. I’m not being falsely modest here—I was genuinely amazed and delighted by the impact of that film. I have gained respect in the network of film archives and people will help me access material because they know that I will not underestimate the film. I made a film some years ago called Women Make Film. It was a big project and the archives around the world really helped. I would go to Bulgaria and say like, “There are three films that you have in your archive, could I see them?” They would strike Blu-rays from the original prints for me, so I’m very very lucky that I can access things.

POV: Do you see this new film as being slightly more overtly euphoric?

MC: It’s different, yes. It’s less. The Story of Film: An Odyssey is a chronology. This one isn’t chronological, and it’s a bit more of a mood piece. As you’ve inferred, it captures a touch of the COVID time with shots of sleeping people. I have a feeling that it will touch people, but you just never know. I’m never confident about that. But I know when Cannes saw it, they phoned me up and the reaction of Thierry Fremaux was very strong. He talked for 40 minutes on the phone about it, I thought that if the director of Cannes likes it, maybe there’s something here! When you’re down in the well of making something and then you come up for air, it’s really hard to orient yourself.

POV: You include elements, from the sleeping people to the hypnotic shots of the streetcars in Minsk, that could be removed and it would essentially tell the same story about films over the last decade. This feels a bit like you writing your own filmmaking into The Story of Film.

MC: You’re right, although it’s not really about expressing myself. Our art schools teach that art is about expressing yourself, but I feel I have no inner world that needs to come out. This is me responding to the world that’s out there. As for the footage that you refer to, the reason we are in Belarus and Minsk is that it’s hard to make a film that is grounded in nowhere.

On the journey in this film, we stop off at New York City, Belarus, Senegal, Mumbai, and we go to a few places just to feel that we’ve stopped and rooted and paused. In the case of the footage from Belarus, it’s at the beginning of the documentary sequence, which is about those filmmakers who’ve really encountered the world, engaged with the world, and tried to say something about reality. Belarus is still in turmoil, and still has a dictator for a leader. It’s a place where documentary really matters. For them documentary is not quasi- entertainment, it’s a mechanism for pushing back against the state.

The Story of Film: A New Generation premiered at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival.