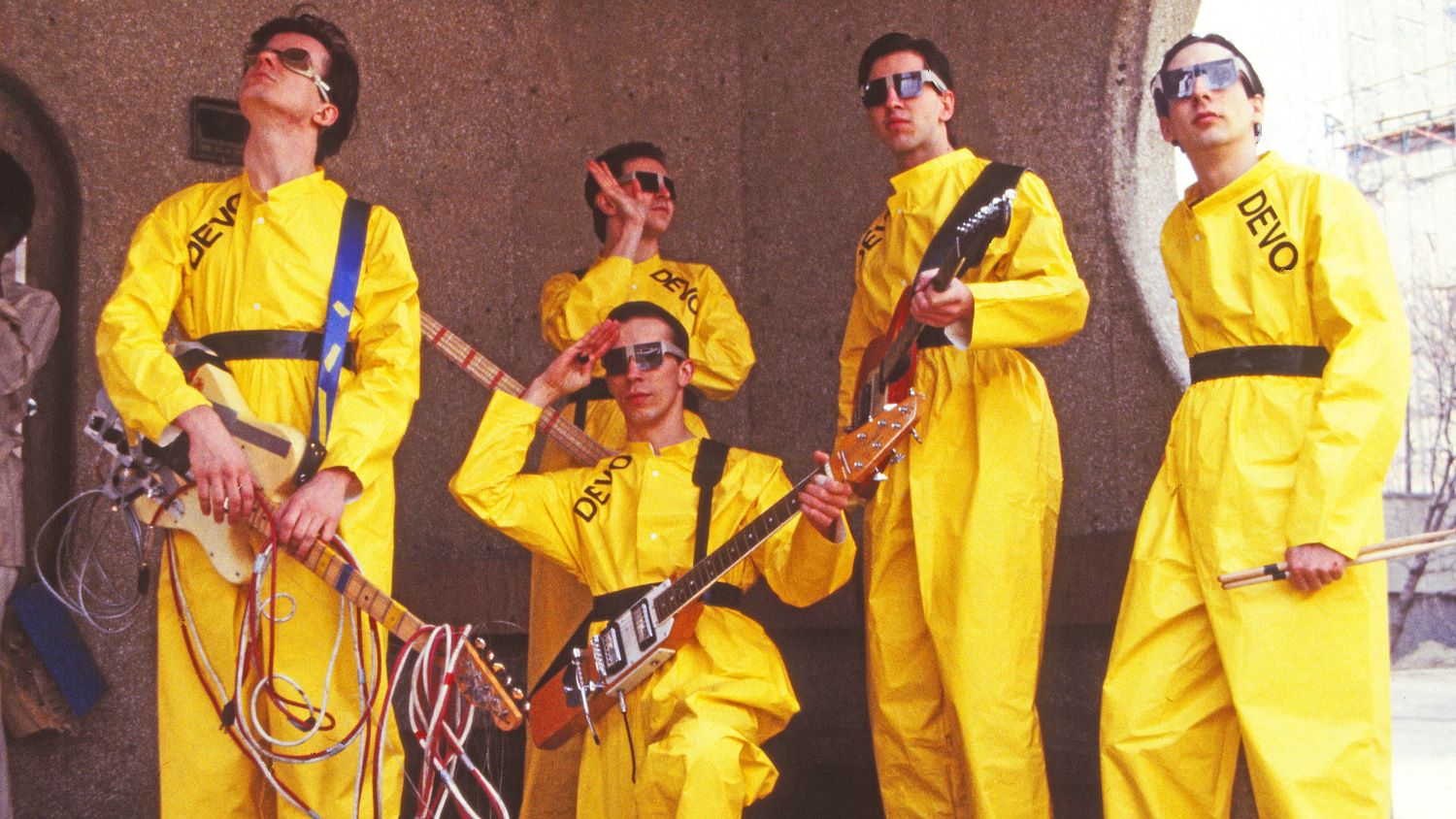

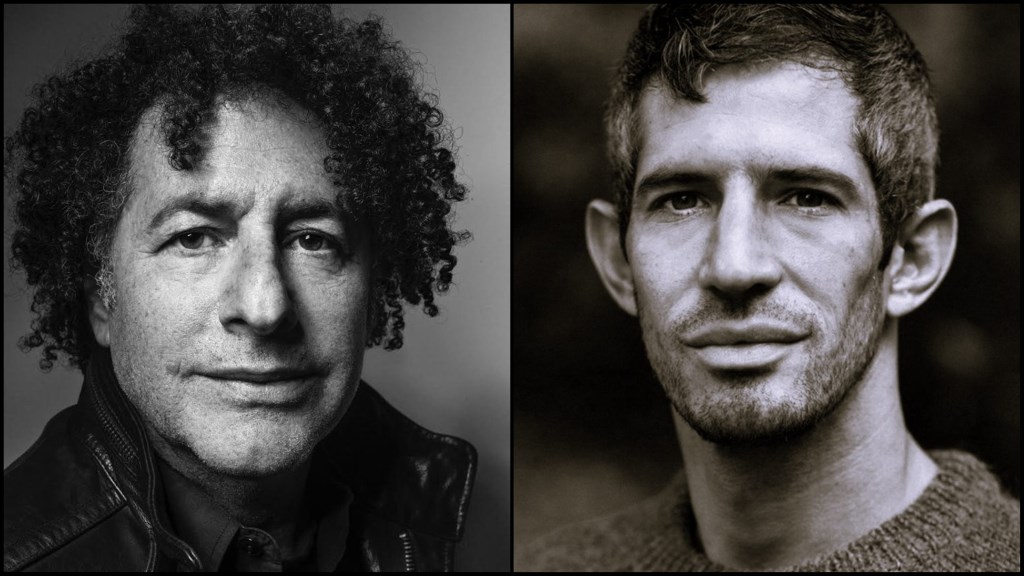

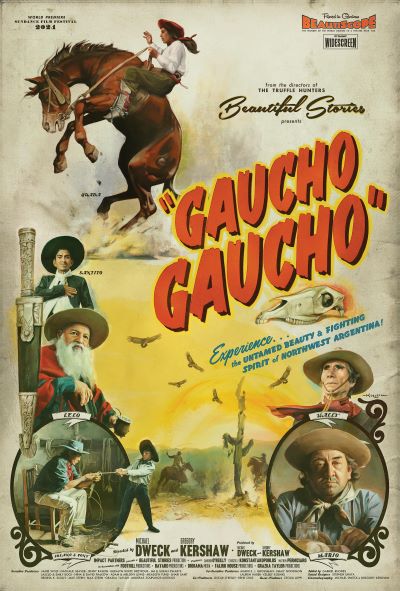

Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw’s Gaucho Gaucho is pretty glorious. Following the success of their very well received 2020 documentary The Truffle Hunters, their latest film is another stunningly photographed vision, this time of Argentinian cowboy culture. Gaucho Gaucho mixes grand mythologies with terrifically intimate moments that elevate the experience from mere travelogue. The film brings audiences deeply within the community and it allows the gauchos’ pace and their voice to dictate the telling.

POV’s review highlights the brilliant camera work, the stunning black and white imagery, and the fabulous characters who are simply a delight to behold. The dusty landscape and its colourful characters permeate every scene with wonderful energy.

Following the film’s debut at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, we spoke over Zoom to the award winning filmmakers about their process, their patience, and how these images were brought to the big screen.

POV: Jason Gorber

MD: Michael Dweck

GK: Gregory Kershaw

The following has been edited for clarity and concision.

POV: It’s been quite a journey for you guys since The Truffle Hunters. I’d like to talk about finding another taciturn group to hang out with. What was the impetus to go all the way to Argentina?

MD: We’ve both been spending a lot of time in Latin America. Gregory’s been down there for 20-plus years, working on different film projects dealing with conservation issues down there. I’m married to an Argentine woman, and I’ve been going down there since 1993. Our projects often involve us looking for communities that are sticking to their traditions and their identities, and where modernity hasn’t really come in and stripped away the soul of these places. They’re really hard to find! While looking for a gaucho community, we looked all over Argentina. We looked at some places in Brazil. We landed on this place because we were trying to find “Gaucho Gauchos.” There are those people who dressed the part, have a horse and they maintain some of the traditions. But a Gaucho Gaucho is somebody who has their own cattle, they make their clothes by hand, they’re still living the way that it was in the past, and these traditions are still ongoing. They sing these songs that are almost like cowboy rap, telling stories that go on for generations.

POV: Like old country ballads?

MD: Yeah, like respetados. They sing stories of their day, often around these barbeques, these asados that they have. It took us maybe a year of research to find them, but there they were in Northwest Argentina, as well as the south of the region, near Bolivia and Chile. It wasn’t easy to get to. Gregory sometimes had to fly 36 hours to Buenos Aires, and then another four hours across the country and then three hours’ truck up north. Then we had to get on a horse sometimes, nine and a half hours to get there, so, it’s not easy to get there, but worth it once we did.

POV: There’s a thing about gangsters and self-mythologizing. You have the mafia who love The Godfather, as we see in The Sopranos. Could talk about navigating this balance, about finding a community that’s able to tell its story on camera, but also recognizing that their lifestyle entails maintaining a mythos that is perhaps performative?

GK: There is a mythology of the Gaucho that is essential to Argentine identity. Throughout South America, there are different forms of this Gaucho culture. Our interest was in going into a place and finding the real people that are behind it. The people that we’re filming, they’re very aware of the mythology of the Gaucho, but also the mythology of the American West. They all know John Wayne. That certainly permeates how they see themselves and how they identify as cowboys and cowgirls. Everyone we were filming with, from early on, we were told that Gauchos are very proud, not just of the work that they do, but of their culture. It extends to how they dress and how they carry themselves.

There’s certain clothing that they wear when they do parades, which is also a big part of Gaucho culture. There can be from a hundred to ten thousand Gauchos, all in their parade outfits which are these handmade, very ornately patterned custom suits. They have special bridles that they put on their horses and they go through town looking their best.

Lela, the 84-year-old Gaucho, always insisted that we film him in his parade clothing. But if you’re going to be a Gaucho Gaucho, that’s part of it, you have to parade, and you have to carry yourself like a Gaucho and dress like a Gaucho.

POV: Let’s talk about the moments that feel scripted, such as shooting the scene in the school where Guada was being admonished for not conforming to a dress code.

MD: We spent a lot of time in these communities before picking up a camera. We spent weeks and weeks trying to immerse ourselves within these families. What we also find is that a lot of situations repeat themselves. This gives us a chance to understand, because we’re coming back over two years, as stories develop. In the case of Guada, her father brought her forth and said this is the woman you should focus our story on. When we started to learn about her, we knew there was this conflict in the school. She refused to wear the school uniform because, as she says, she wanted to stick to her traditions and that it’s not very practical given that she’s working on the farm with the horses in the morning.

We knew that conflict existed, we spoke to the headmaster of the school, and the opportunity came where we could film this conversation between the two of them. We didn’t know what was going to happen. It took a couple of days for them to agree to do it, and then we just let the camera roll. Anything could have happened, but we knew that it was bubbling up, everybody was talking about her—her friends were speaking about it, her parents were talking about it.

POV: But the headmaster knows the camera is there. You are not capturing something because you’d been shooting at the school for weeks. You’re capturing a conversation that you knew was going to take place. Is that a fair statement?

MD: We knew that there was going to be a meeting, but the meeting could have gone any way. We didn’t know what was going to happen.

POV: One of the other things you do is shoot in black and white. You’re like, “Hey, we’re going to mythologize this story as they’re mythologizing themselves. We are going to see them in the way that they see those John Wayne movies, and give them back the imagery that they are so themselves aware of.”

Both: Yeah, that’s true.

POV: Where in the process did that decision to film in black and white take place? On a practical level, I assume you shot everything in colour, and then did an incredible black and white grading that makes it look like a Kurosawa film?

MD: We started looking at the world through colour, through a look-up table, and then we switched to black and white. This experimentation happens at the beginning of any film project where we’re figuring out how to capture the world in a way that reflects what it feels like. In black and white, it clicked for us. There’s something timeless about it. There’s something that allows you to focus on the detail and the unique textures of the world. But it does go back to what you were talking about earlier. We are acknowledging, as we’re making a film, we are there, we are directors, and we are shaping it through the camera. We try to do it in a way that the people in front of the camera can forget about it, but we have a very deliberate approach to every frame that we create, and [where] we place our camera, and [how] we use our camera to create a feeling for the audience.

That’s going to transport our audience into the world that we have this incredible privilege of being able to participate in. I guess it is different from the fly on the wall approach. We acknowledge our presence and we shape the visuals of the world. We try to have a depth of understanding with the people in front of the camera, where we know how to position ourselves in a way that allows us to disappear and for them to be comfortable. But what we’re searching for in all that is the same as any artist. We’re searching for a truth. We’re searching for a fundamental emotional truth. The way that we go about achieving that is maybe a bit different from other documentary filmmakers.

GK: We also film one shot a day. We spend quite a bit of time waiting. For exteriors, we only shoot after the sun sets. That’s for two reasons: first, it gives a very painterly look, and second, because we’re high desert, the light is so harsh there, we had no choice. But because the camera is not moving, too, and because we keep coming back and immersing ourselves in the family, having wine with them a lot, having a lot of meat with them, a lot of asados, they eventually forget about us. The camera’s not in their face. It’s not moving. So the camera becomes part of the family as well. When people see these scenes that they think are set up, they’re not. They’re maybe two minutes of a two hour meal, and that meal we probably filmed five or six times because we’re always in their homes.

POV: Given how this is tied to their self-mythologization, how often, if ever, did they want to go see a shot play back? How often did they want to see the composition? How often did they want to help shape a shot?

GK: Well, all the time is the answer. After almost every take we would have the people that we were filming come and look through the viewfinder and play it back for them. We do this in all of our work, but it was especially true in this film. There’s a conversation between the people we’re filming and how we’re deciding to tell the story, but we’re asking them, “What should we film?” What do you think would be interesting for us to follow with our cameras? They’re giving us ideas and then we’re filtering that through our storytelling, trying to figure out what ideas will actually translate into cinema, what ideas will translate into a story, but it’s very much an ongoing dialogue.

MD: An example would be when we show the Choque family, who you see throughout the film, who are lacking water. We shot the camera car scene, which one of the opening scenes of the film. You see the horses galloping and the camera is galloping with them. We showed that to them, and they wept. They completely broke down, which had never happened before. But that actually helped break down a wall. We were filming them—at that point we were in year two, one of the last shots—and that really broke down. It just eliminated these walls we had between us and them at that particular moment.

POV: Was that literally one of you hanging off the side of a Jeep? You don’t have a Chapman crane, you don’t have a Russian arm, what are you shooting with?

GK: We knew we wanted to bring the audience into the experience of being on a horse. I’ve never seen anybody ride better than a Gaucho, and there’s this connection between human and animal. We wanted to immerse the audience in that experience. We experimented, as we always do, trying to figure out what’s the best way to do it, and we realized that we had to be going at the same speed as the horse. There was no other way to do it. We were shooting with a fairly big camera when it was all set up, so we certainly weren’t going to run at that speed, and we realized that we needed a camera car. A camera car that could go up mountains and over cactuses. We had to get a camera car brought on a trailer across the country from Buenos Aires: 25 hours of driving and then to all of our different locations, which were all on mountaintops, these windy dirt roads. There was an arm on the front of it, not quite a Russian arm, but it was an arm that provided some stabilization. We were able to go at the same speed of the horses. Normally, our crew is so small, it’s just Michael and myself, and we have a few other people from the community helping us out, but with these shots, it was the full-on Mad Max experience. It was amazing to film.

MD: We broke the camera car.

GK: A few times, in a few different places.

POV: What was your main rig, and how did that change over two years?

MD: We shot consistently with the ARRI ALEXA Mini LF. ARRI has been really supportive of our work, and they gave us the first zoom lens that they ever made. While that lens was being made, they loaned us three prime lenses, but that was just a nightmare. In that area, it’s so dry, there’s so much dust everywhere, and it was not easy to move around. That zoom lens was perfect, and that’s what we shot with for the entire film. The lens is being repaired right now! After that camera car shot, that cost us quite a bit of money to repair that.

POV: You talked about the Gauchos and John Wayne, but let’s talk about your relationship with westerns.

POV: You talked about the Gauchos and John Wayne, but let’s talk about your relationship with westerns.

GK: As filmmakers, those westerns are in us. We’ve experienced them, but we’re really not directly referencing any films as we’re making. We can’t move away from our influences as filmmakers, but we’re not looking to any of those as we’re shaping the story. What we are looking to is the community. Everything we do, everything we put on the screen, we try to make as pure a reflection of what we’re experiencing as possible. We capture the people we’re filming in the way they describe their world, the way that they think of themselves.

MD: One thing we do, as we did in a very subtle way with Truffle Hunters and with Last Race, is that we attach sonic profiles to each character. They’re very subtle, but they exist. The reference to the western is that Lelo, the guy with the white beard—if you listen carefully, there’s an old rusted windmill on his property. That’s, of course, reminiscent of Once Upon a Time in the West, so that’s apparent, but that might be one of the few references to American westerns.

POV: You talk about shooting for hours, something that digital cinema provides you. When a great moment happens, you must think, “Oh my God, this is going to be the scene.” How often does that element stay in the final edit, and how often in edit do you find thing that maybe didn’t seem like a big deal at the time, but retroactively became foundational to the story?

MD: I think that happens quite a bit in the edit, actually. Back to the example of that opening scene with the galloping horses, because we’re looking at a small viewfinder, it wasn’t until we saw it in the edit that we realized that really defined the entire film. There was something about that scene that brought us to our knees emotionally, that really defined freedom to us, which is what this film is really all about.

Because there’s so few shots—147 shots in this film, Truffle Hunters had 107—editing is tricky. Once you move one little piece, the puzzle changes radically. There is quite a bit of discovery. We now work with Gabriel Rhodes on crafting this non-traditional structure. We have no coverage. On Truffle Hunters, after two days, the editor said, “Where’s your other hard drive?” We said, “We have no other hard drive!” “Where’s your coverage? Where’s your people?” “We don’t have that either!” It takes a while to understand this type of storytelling, in an edit, how to assemble these scenes and juxtapose one on another. We have to know how to inject humour, irony, and different emotions and character arcs. In the end we crafted it as a three-act structure, but delivered in a very different way.

GK: So much of the process for us is emotional and intuitive. When there’s something magical happening in front of the camera, you feel it, and it usually is very apparent at the moment of filming. They do speak Spanish, but there’s a lot of specificities to the local dialects, so even people from Buenos Aires didn’t understand much of what was being said. We understood very little, so we wouldn’t understand every word, but we would be tuned into the feeling of what was going on. That was always our guide. Of course, when we got into the editing room and we got translations, there were lots of wonderful surprises because there was so much poetry in how they speak. Some of the stories that Lelo tells are mind boggling.

MD: Take the scene with Sentito and the priest. It was so amazing because Sentito was so shy. We’d known him for a while, we’d been filming him for months in that radio station. He has a radio show, from 5-7 every single night. He’s on the radio, and the people in the town have transistor radios hanging from their horses, listening. They’re die-hard fans. We were listening to the conversation carefully, but then once we got the nuanced translations back, we could not believe how what he was saying was so beautiful.

Tati, Guada’s father, speaks like a Buddhist poet. Watching their relationship unfold in front of our camera over those two years held so many beautiful moments. But at the end, that was one of the last days we spent with her. [Guada] went into this amazing story about her upbringing and then she asked if he was proud of her. That was part of a three-hour conversation, which easily could have been half of the film.

POV: You talked about not having B-roll, which is not having a plan B, basically. How quickly did you lock into these characters as the ones you were following?

GK: It goes back to the title, Gaucho Gaucho. As we started our research process and as we learned of this idea of the true gauchos, we started asking around everywhere we went. Tati Gonza’s name kept coming up in every conversation, along with Mario Choque and Lelo Calrizos. These were the people that we went to see and talked with very early in the process and then, as you start talking to people, some people reveal their stories to you very quickly. Wally, with his story with the condors, told us immediately. He said the world is in chaos, the world has been turned upside down because condors are now attacking live animals, and that’s something that never happened before. To us, it clicked immediately that it was a very cinematic story, and we knew we were going to follow him.

For other people that we filmed, we were fascinated by them; their worlds were beautiful and so unique. We didn’t know what the story was, and it took longer to discover that. That is always a bit scary, especially when there’s so much time and resources that go into every shoot. I guess there’s a fundamental faith that we had: if we follow people we find fascinating, people that are passionate, then a story will eventually emerge.

POV: I hate to tell you, that’s also a metaphor for how your films work. Is that I have to have faith in you guys as filmmakers, that you’re not just going to show me a bunch of aimless images, that you are going to take me on an actual guided journey. How conscious are you of general audience reaction when you’re assembling this? How can you be successful if not everybody gets your film?

MD: We do want to teach people to learn how to see again. We want people to spend time observing all of the details in these environments.

GK: As Michael was saying, we do want people to have a chance to spend time in a new place and experience the texture of the world. That is very important to us. But the storytelling goes back to this idea of myth, the mythology. There is this mythology of the Gaucho, and there is this imagery that comes with it. What we’re hoping to do over the course of a two-year film is to go beyond that mythology, to go to the humanity of the people who live out that mythology. We’re looking for stories that are universal.

We got a lot of warnings when we started filming in the Gaucho community. People said we needed to be careful, and a lot of people in Argentina thought that there was a sense of otherness. What we’re always trying to do is break through that sense of otherness and find the connection and the deep humanity that we all share. We found it everywhere we filmed; there’s a fundamental connectedness that we all share. That guides our process, trying to get to that.

POV: You ate like kings last time in the land of truffles, I want to talk about the food. They’re raising cattle, and obviously this is another food culture. Could you talk about the culinary, sensory sensation of spending time with the gauchos?

MD: Getting to know these communities always involves drinking a lot of wine, and a lot of asados. We got used to that kind of diet. It’s interesting that most of the interactions in the family happen around these barbecues. They share mate, which is yerba mate, that’s a very important part of their lives. It’s also an honour to be invited to an asado for an outsider where they’ll have a lamb or different parts of a cow. There’s also these different blessings to Pachamama and there’s also Christian traditions that cross over into Indigenous prayer. Over food, a lot of the immersion into the families happened, and that helped us to understand their lives and their history.

GK: One thing experienced in all of these meals too is the connectedness they have to the food that they eat. Our two most recent films have been around cultures where food is at the centre but it’s because, when you get down to it, that’s one of the fundamentals of human life. We’ve become so disconnected from the food that we eat, where it comes from. But when you’re eating a Gaucho meal, you know where the food comes from. Most of the people that we were filming with are very self-sufficient and they have been a part of raising the cattle, and raising the crops. The food has a much different meaning. There’s an element of spirituality at every meal because it comes from their hands, from their earth, and from their traditions.

MD: And everybody participates. You see them making empanadas from flour: they actually grind their own. We don’t show it in the film, but they have these stones that look almost prehistoric because they’re big blocks of granite that they’ve been using for generations, their version of mortar and pestle, grinding down the corn that they use to make the flour. The family gets together, you see the can that they’re using to shape the tortillas that they use to make the empanadas—that’s a joyous part of this family life, because everyone’s working together to prepare the meal. The men are called asadors. It’s a rite of passage, after you’re doing it for five, six, seven years, your father finally comes to you and says, “Ok, you’re officially an asador.” The final dinner scene in the film where [they] say, “Now you have enough to fit into your saddle bag,” that’s an expression: And you are now fit to be married. Now you can make somebody a good husband. That’s the rite of being an asador.

POV: It’s a gaucho bar mitzvah. That all works out well. Obviously, Argentina is going through complications economically, socially, politically. How have these upheavals in Argentina over the last year reshaped the Gauchos experiences?

MD: I think they’re insulated from some of the biggest swings. While we were there, the currency, went from one dollar to two hundred and fifty pesos, to one dollar to a thousand pesos. The inflation is almost incomprehensible. In Buenos Aires, they feel the swings much harder. The Gauchos are a bit more insulated from that in the communities, but they are attached to the national economy and it does have an impact.

GK: We were surprised—they don’t really expect any handouts from the government. They were pretty self-sufficient, self-reliant, and we never heard anybody say they were wanting. There was so much joy in this world, considering what was going on there because a lot of it was being traded with barter. If somebody has meat, like in the Choque family, there’s no legal system in place to sell meat. So it’s done kind of in a black market trading, so you’re trading beef for pomegranates. Or you’re trading for sheep skins, to use as a saddle, so this bartering exists in that economy which is pretty interesting.

POV: What impact did that have on the cost of production?

MD: The economy is so weird there, sometimes it’s an advantage, sometimes it’s a disadvantage. The dollar seems to always get stronger, but sometimes, it was never to our advantage, depending on where we were going. It was difficult to keep because the rate fluctuates sometimes five times a day, so it’s difficult to figure out a budget when you’re working on a production in a place like this. From week one of your production to week two, it could have swung 25% either way. It’s bizarre.

POV: How do you think the Gauchos will be changed by your film?

GK: Well, two Gauchos came with us to Sundance, Guada and her father, Tati. There’s a lot of nerves going into Sundance, regardless of the film, but they were there with us during the premiere, and they had never seen the film before because we had just finished four days prior. They were coming for the first time on a plane to a small little town that gets taken over by Hollywood for a few days. They were going to see themselves on a big screen and in front of a bunch of strangers. We had no idea how they would react, especially Guada—we show a lot of different parts of her journey as she’s becoming a Gaucha. But she saw it and she loved it.

Both she and her father were very proud and I think it goes back to this idea of the mythology of the Gaucho that they’re very in tune to. They know that they have special and unique in this world. I think they have an understanding of how the world is changing, as we all do, and they know this connection to tradition, to community, to the beauty that their culture holds. They want to share that with the world and I think they saw this film as a means to doing that.

MD: We got together with all of our [executive producers] the other day, and Tati and Guada were there, and they asked a similar question. Tati said, “We might be separated geographically and economically, but we all share the same heart. And we’re all human.” He said we’re not going to be changed, all I’m realizing now is that we’re all the same by taking this journey.

Also, we give back to the communities with all of our films. With Truffle Hunters, we raised quite a bit of money and we’re concerned with cultural preservation because in Italy, they were clear cutting a lot of trees, and we didn’t want that to happen to the forest where we filmed—the truffle hunters would have no more truffles. That enabled us to buy a tonne of land, and we have almost a hundred acres that are preserved there. We have a wine company we started, the Truffle Hunter wine company, and all of that money goes towards that effort. It’s now self-sustaining. 15 full time volunteers have planted 1200 oak trees. We’ve reintroduced three types of birds. We’ve redirected the river to where it’s supposed to be.

We’re doing something similar in Salta, where the gauchos are from. We’re going to be meeting the needs of the characters in the film, and doing some tests also that will benefit the greater communities that we were working with who are dealing with water, education, and climate change. We have engineers working on the ground already. So this is going to be hopefully a long relationship.