Devo

(UK/USA, 95 min.)

Dir. Chris Smith

Programme: Premieres

Once upon a time, in the small college town of Kent, Ohio, art students Gerald Castle and Bob Lewis began to incorporate into their works ideas that challenged conventional consumerism and conformity. In 1970, they met Mark Mothersbaugh, a bespectacled, offbeat individual who had received from one of his teachers a pamphlet by Bertram Henry Shadduck titled “Jocko Homo Unbound,” preaching that humans were moving backwards rather than progressing. As per the cover of the document, the notion of “D-Evolution” was at the forefront of a current cultural crisis.

And thus Devo was born, the series of counter-cultural (and counter-countercultural) notions that soon became the basis not simply for works of graphic art, but also the form of musical expression by the group of the same name. When four people died in the Kent State shootings, immortalized in Neil Young’s composition “Ohio,” they felt they were at the epicenter of a catastrophic numbing of society, and that some shocks to the system were required.

And so here, decades on, the story of Devo is told in Chris Smith’s effective yet strikingly conventional bio-doc. Formally, it’s a relatively straight-forward affair, and the confetti-like visual oddities that are drawn from the various periods of the musicians’ careers feel almost expected as the trajectory of the group unfolds.

With the now-middle aged men providing details about the early years, family members also participate to speak about the group lineup, the early experimentation, and the usual dross of these rise/fall storylines. There’s plenty of animated bits, plenty of strange collisions and collage elements to make it feel off kilter, but, in every way save for the superficial oddities, Devo is narratively as regular a rock doc as any.

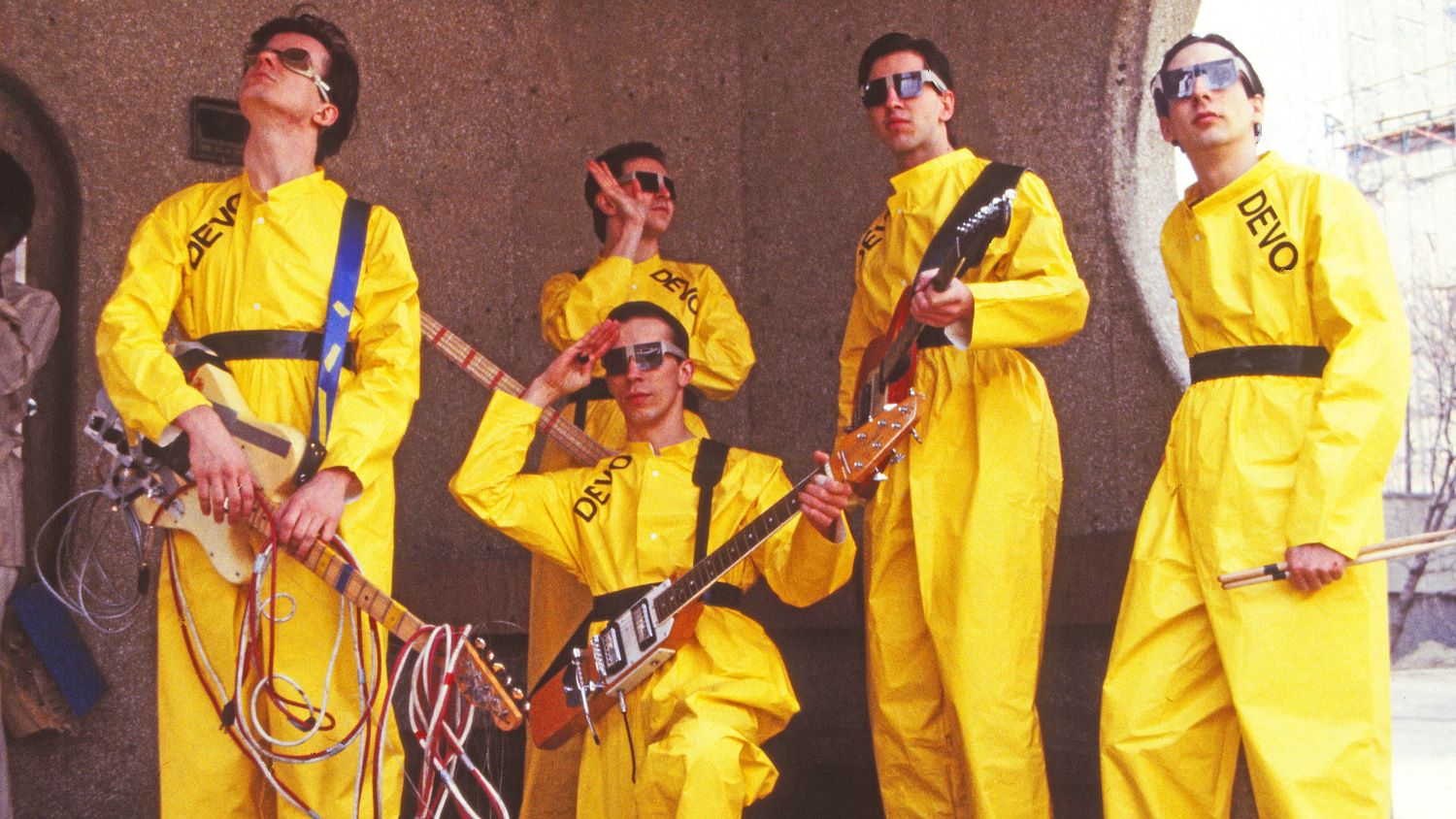

What set Devo apart back then, and certainly helps the documentary rise from being something disposable, are the strong filmic elements that were always part of their shtick. Long before it was fashionable, the band would create video or film records, augmenting their musical output through visual means. Presaging the MTV revolution, they used many of the tropes of the Mothersbaugh’s working class environs as a type of uniform, donning janitors’ clothing and safety helmets to emphasize the otherness of things unremarkable or banal.

Smith, forever to be celebrated for his sublime American Movie, provides a clear timeline for the band’s rise, from early performances where most of the people would abandon these “headache music” drone-a-thons, through to their live gigs in Akron and finally to club shows in L.A. There, they discovered that tracks that played sludgy and raw in Ohio were, when sped up, commensurate with the punk ethos percolating in the ’70s.

After some ubiquitous shots of the CBGB scene, Devo as we now know it emerged with their debut major label album, one that, as seems inevitable with this group, was complicated by the result of the gormlessness of the band members. With both Warner and Virgin taking a chunk of their wares since the musicians’ revolt against conformity meant that they didn’t have lawyers or read the fine print, it was clear from the outset that this group had grand ideas that couldn’t upend the codified rules of the music business.

Once MTV launched a few years later and was starved for product, the quirky band soon had a platform that even major label success could never have fully anticipate. The funny hats, goofy movements, and nuclear-fallout fashion mirrored the likes of other so-called “new wave” bands like the Talking Heads, themselves art students who rode surrealist waves. Yet Devo was, throughout, very much enriched by its early working class environs.

The film’s eccentric elements and wild asides seem, almost implausibly, a slightly conservative way to tell the tale of this band. While the likes of, say, Todd Haynes’ Velvet Underground brilliantly fused form and subject, Smith’s record label-produced film is not nearly as weird as it purports to be. Maybe that’s for the better, as it’s certainly a fine way of moving beyond the one hit wonder-ness of the “Whip It” band, and properly contextualizes that madness within a greater ideological whole.

Yet for fans, this is all pretty old hat. These stories are more than well-tread (especially since many interviews from the musicians are from their late careers in the ’80s). It makes for a very watchable film, for sure. But with the tales of their rise and fall, infighting, Spinal Tap-like rotating drummers, record label shenanigans, and the emphasis on the earlier records while giving almost no attention to later albums, it all feels it oddly feels far more “normal” than Devo’s own mythmaking.

The carefully curated soundtrack features tracks by the band, from Mothersbaugh’s own extensive output, and from other groups from the era. A nice story about John Lennon (complete with animated biting face) and the “ya ya” chant also show hints of Devo’s trademark lunacy, but it’s somehow expected lunacy for such a project.

Devo famously asked us “Are we not men?” It’s safe to say, unsurprisingly, they are. But, indeed, they are Devo. They were men and they were Devo. They were young men who held ideas that were half-baked but engaging, had hits that were fun, and had a career that continues to influence musicians to this day.

And that, despite any cynicism one may have about the machinations of Devo, may, like the band itself, not really be that radical. But it’s still, as Smith’s film constantly preaches, pretty wonderful.

“Ya, ya, ya, ya, yayayayaya, ya,” indeed.