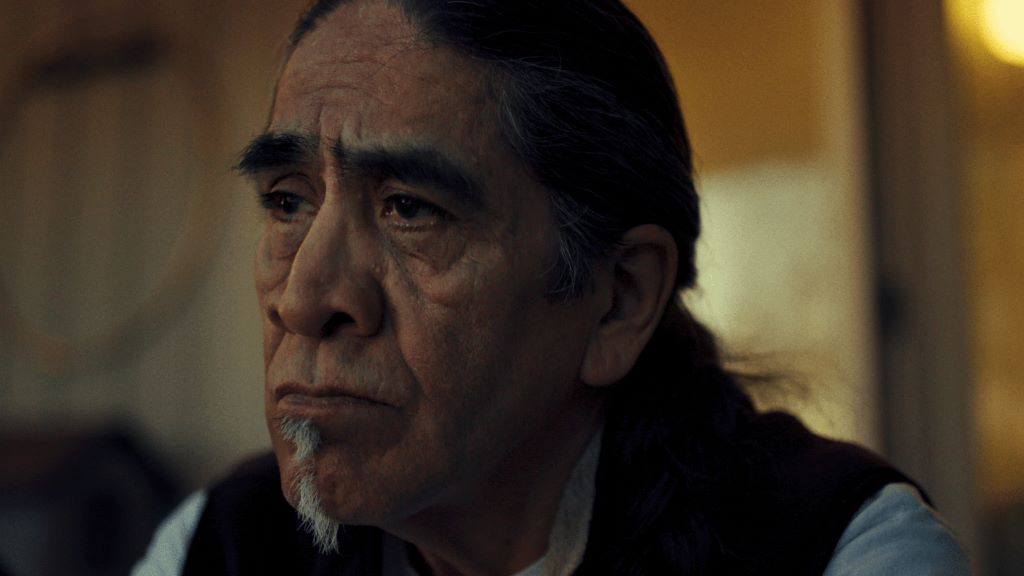

Emily Kassie and Julian Brave NoiseCat have spent years bringing the story of Sugarcane to life. The film, which won the directing prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, charts a deeply personal journey of uncovering family trauma, while providing greater context to the horrific legacy of the residential school system and the ways in which the Catholic Church barbarically and abusively ran the institutions.

As mentioned in POV’s review, the film assumes multiple modalities. On one hand, it plays out like a police procedural. On the other hand, the filmmakers show quiet moments of reflection, or even deeper, more challenging conversations that the camera can’t even bear to witness. The result is a deeply moving film that’s journalistically rich, visually compelling, and politically and socially vital for moving the conversation along. Sugarcane generates entirely new avenues to explore if the goal for both truth and reconciliation is to be more than a catchphrase.

POV spoke with the filmmakers following Sugarcane’s debut at Sundance via Zoom, where they explained the origins of the project, their working relationship, how audiences have responded, and more.

POV: Jason Gorber

EK: Emily Kassie

JBNC: Julian Brave NoiseCat

The following has been edited for clarity and concision

POV: Congratulations on the film. Can you talk about the journey of bringing it from a personal conversation to a public one? Did this start as something more intimate, a father and son story between Julian and his father?

EK: Julian and I worked our first reporting jobs together almost a decade ago at The Huffington Post. He was literally at the desk next to me. Ever since then, we’ve been trying to find something to work on together. Jules has had an incredible career as a writer and a journalist and is an incredible storyteller. I’m an investigative journalist and a visual storyteller. I’ve been making short docs all over the world and reporting on human rights abuses and genocides in Afghanistan, in Turkey, in Rwanda. When the news broke of unmarked graves at Kamloops, I knew in my gut that this is where I needed to be. I’m Canadian, and the final year of the residential school system in operation was my first year of kindergarten, yet I learned nothing for my entire education in Canada. The first thing that I did after reading that article and deciding to do this was to text Julian.

JBNC: When Emily texted, I told her I had to think about it. I had just signed a book contract and I had no clue how to write a book. This was to be my first film, and I had no clue how to make a film, either! To do both of those at the same time felt a bit irresponsible. At the same time, this is something I didn’t initially tell Emily, but I knew that there was a very painful connection to the residential schools in my family and I wasn’t sure if I was ready to go there. I took a couple of weeks to think about it, and Emily forged ahead.

EK: While Jules was thinking about it, that same day I went looking for a nation that said they were going to do a search. I was scouring the Internet and I found this article from the Williams Lake Tribune talking about Chief Willie Sellars and the St. Joseph’s Mission. I wrote an email to the Chief that day, and he called me back that afternoon. He said, “The Creator has always had great timing for me”, and that “just yesterday, our council said we need someone to document this search,” and “we’d love to have you.” By the time I spoke to Julian, I had already booked flights to go, and I had spoken with council, and I was well on my way. I had been waiting to hear what Julian wanted to do, and when I heard from him, I said, “It’s so wonderful you’re open to doing this, I’m going to be following a search at St. Joseph’s Mission…”

JBNC: —And there was a long pause. I said, “Wow, that’s really crazy. Did you know that’s the school where my family was sent, and where my father was born?”

POV: And then we really have a movie.

EK: It was full body chills for me. We went there and we spent two and a half years until we submitted the film a week ago to Sundance, giving it everything we’ve got, every inch of ourselves in a really beautiful collaboration. We built an incredible team around us as well, so it was a really amazing collaboration of artists circling around this critical story.

POV: What does it mean for you guys to be playing this to an American audience, specifically a Park City audience? How differently do you think it would have been treated as an artwork if it had been thought of as something as “provincial” as making a Canadian debut rather than an American debut?

JBNC: There were three times as many schools in the U.S. that took hundreds of thousands of children away from their families, and yet there is not a parallel conversation here in America like there is in Canada about the legacy of Native American boarding schools. Our careers are largely based in the U.S., but we also hope that this film helps drive a conversation down here about what is essentially the same history. For example, when we were in the archives filming Sugarcane, we came across records that showed Oblate priests being moved not only between schools in Canada, but also to schools that the Oblates ran in the U.S. The notion that these are separate systems, separate institutions, is really not borne out by the facts. These networks extended through the Church across borders, the philosophy was definitely one that crossed borders and the history is one that crossed borders. This is a content-wide history of how this land was taken and how Native people were attempted to be assimilated and culturally annihilated.

I think that this story just deserves the biggest platform that there is in film. Obviously, there are wonderful film festivals in Canada—we’re hoping to bring the film to them. But Sundance is a very special film festival, especially for documentaries, and that was why we wanted to bring it here and to have a U.S.-based production in part. I think here is a distinct and different reaction that we’re going to get in the U.S. and Canada, so it’s almost as though we’re going to have two impact campaigns, and two parallel releases of this thing. It’s going to have a life in Canada, and it’s going to have another life in the U.S.

EK: The way that we made this film is a bit different than anything that’s come out yet in the last few years around the residential schools. This isn’t a news-based film—it’s an intimate character [study] that follows a cinematic journey of people grappling with their family’s pain. It taps into universal themes of fatherhood and parentage and identity that people can connect to universally. I do think that it’s going to bring a new element to the conversation, even in Canada. But I also think that there’s also a journalistic significance to the film. Our film doesn’t just grapple with the verbal, sexual, and physical abuse and cultural genocide that has been in the Canadian conversation and rhetoric. It also is bringing to light some of the first instances of infanticide, of children born by priests, babies being thrown into an incinerator and burned alive.

JBNC: And to unwed mothers.

EK: I think that that is news breaking. It adds a different dimension to this conversation: we’re not just talking about the Catholic Church and its history of sexual abuse, we’re also talking about murder and an actual genocide against these children and communities. I don’t know that either country has grappled with that yet.

POV: What is the experience like of having people say they had no idea any of this was taking place?

JBNC: This is a history that even the people who survived it do not often talk about. My grandmother really doesn’t speak about her experience in residential schools beyond two stories. There’s one story about how she was hidden by her grandparents in a trapping cabin so that she would avoid being taken away to the school [but] she was still found and taken away. The other story is about how she and her friends at the school would call the priests and nuns the kenkéknem, which means black bear in our language [Secwépemc]. They would call them that because the black bear is a predator. So there is very limited conversation about this even within my own family, my own community.

This film is trying to encourage people like my father, or like my grandmother, to have those conversations. I think that’s true not only for intergenerational survivors of residential schools and boarding schools, but I think it’s true for all families that share this pain and trauma. It’s important that people identify those folks in their lives and go there and are inspired to have those conversations because of this film.

EK: Another important piece of that is that the past is present in our film. Not only did the last school close in 1997, which is very recent, but people are still dying from what the schools did–of suicide and addiction from that trauma and cycle of trauma. The death toll of St. Joseph’s Mission continues to climb. That’s one of the messages that we really wanted people to understand: When they see people suffering in Indigenous communities, they understand exactly what was put in place to break down families, to strip them of the things that allow them to thrive, their land, their culture, their connections to one another.

POV: There are moments of deep intimacy caught on camera, but there are also moments where the camera holds back, like when you go into your grandmother’s house, Julian. We hear what’s taking place, but we do not see it. The film follows characters to the Vatican. Can you talk about how you divided the labour in terms of directing, especially in moments where you might have disagreed about how to capture something?

JBNC: Emily and our director of photography, Christopher LaMarca, who was with us in the field almost the whole time, shot the film, so I’ll let her speak a little bit more to that. When Em and I were in the field, we would be processing things in real time, talking about how we would approach different scenes before we got there, when we were in the room afterwards, and then a core part of our collaboration was [talking] after the day was over, and still in the edit, actually. We would gather around the couch, usually with some sour gummies and some other junk food, sometimes a Blizzard from DQ, and talk about what we’d shot that day. It became a mind-meld where we developed a shared vision about what Sugarcane could and should be.

EK: I am a director who shoots. It’s my way of relating to things. I can’t not shoot. I wouldn’t know how to feel the story without my camera. Julian described it as if he was standing on the mountain and able to see the big picture. I was kind of up in the weeds, down in the river, moving rocks around. We were bringing different perspectives to it, also as an insider and an outsider. But for the visual vision, Chris and I wanted to create something that was really intimate, that took you deep into this world and made you feel like you could connect.

The Rome trip in particular was an interesting one. Chris had to stay back and film Canada’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, who decided to make a visit to Williams Lake and see Chief Willie at the exact time that we were going to the Vatican, which is obviously a bizarre moment in the film. Jules and I went to Italy. It took a bit of a trickery and some creative decision making to get access to all of those rooms where we were not wanted by the Church mostly.

Jules and I really wanted it to feel like a nightmare from Rick’s POV. [Rick is a residential school survivor who attends as part of an envoy to the Vatican to share their stories.] There’s a moment where Rick is standing under the Sistine Chapel, and it’s out of focus because it’s about his reckoning with this world.

POV: Our focus is on him, not on the painting.

EK: Exactly, but it’s also about him struggling with how this identity is part of him or not part of him. Being in the room with the Pope, I didn’t really have a choice. I had to film it on my phone because of how I was getting access to the room. That kind became this little journalistic iPhone moment. But the most important thing for us was to feel Rick’s experience.

POV: Some filmmakers may have insisted on going in when the discussion with the grandmother took place. I think that it is perfectly understandable why that did not happen, but if you were not the subject of the documentary, Julian, there might have been a push for the cameras to be there. Can you talk about times where there’s an active decision to not do something that may be better for the film, on a narrow level, but not better for the film on a greater level?

JBNC: Emmy usually shot me, so that extended to filming my grandmother, my kyé7e. The scene where me and my kyé7e are in her house and she’s not talking about the experiences that she had at the residential school, Emily’s behind the camera in that moment. She’s also there at the moment when the announcement of potential unmarked graves happens and we’re all gathered around to listen. Em is really good at building trust with me, obviously, and then also with my family. They really love her. They love spending time with her.

You can’t really tell in the documentary, but I actually lived with my dad for the making of the documentary, so Em spent a number of nights at our place. She’s always welcome there, she’s always welcome with my family in Canim Lake. My aunt, who appears in the film briefly, was here in Sundance for the world premiere, and the last thing she told me was to give my love to Em and Chris, our director of photography. There was a lot of trust built up there, which also meant a lot of mutual understanding. You want to be present for as much as you can possibly be present for, but at the same time, you don’t want to extract, you don’t want to be exploitative, you want to meet the story and the people where they’re at. And so there are a couple of moments where the camera does not follow.

POV: There are people that will object to that. There are people who will say that, cinematically, filmmaking-wise, “That showed a lack of doing something that other documentarians would do.” I want to address specifically that concern.

JBNC: There’s two moments in the documentary where the camera does not follow. The first is after my and my father’s interaction. I go to the bathroom and I wash my face and I cry and you can hear the water running. That is the first moment where the camera does not follow, which establishes this language, which is part of this intergenerational pain. The second is the moment that we’ve been building to the entire film where my dad goes and finally has the conversation with his mom. Of course, there are parts of that conversation that did not make it into the film. What we’re gesturing at there is the private and intimate nature of some of these family realities. At the same time, we use that drone shot to configure all of this within time immemorial, within the history and landscape of the people who are holding this pain across generations.

EK: The audio is incredibly intimate. Being able to sit with it and have people in a darker space with a meditative image that starts dark and opens up to light and having that pain break open, and in conversation with the land, is an artistic choice that brings it home. It’s been people’s favourite moment of the film. They have come up to us many times about that shot and how glad they were that that was the choice that was made, and I think it’s speaking to something bigger. This is her pain, and it’s so great that she cannot go there, even as an older woman, even as an elder, even in this quiet moment where her son and her grandson are asking her, even without a camera in the room, she can’t go there.

JBNC: The image also echoes an image right before, which an image of the river, which the main artery of life of our people. It was intentional and it was built out of a simultaneous sensitivity to our subjects and my family and also some very long thought-out artistic decisions in the field and then in the edit.

POV: What does it feel like for you guys to be at this part of the journey, this part of the river, knowing that there’s a lot of river to go, and there’s other tributaries to explore after this?

JBNC: It was really special to share the film and the world premiere with our participants who are going to remember this for the rest of their lives, and especially for me with my dad and my family. He’s an artist as you see in the film, and he’s both incredibly moved by the way in which we treated his story in this film. I think he’s really proud of this as a work of art, which, as the child of an artist, that means a lot to me.

POV: How are you doing? You’ve lived this story so much. How are you guys doing at this moment, given everything that’s taken place?

EK: It’s a roller coaster! I mostly am in a place of deep gratitude and relief and release. I think this, for me, was about Rick Gilbert, former Chief, who passed away during the edit of the film. That was really hard and painful, and he meant the world to us. I spent a lot of time with him and his wife, Anna. This film is part of his legacy and it will live on. He is a hero, and people see that and they stood on their feet for him. This one’s for him.

JBNC: The leg up that nonfiction has on fiction is that it’s about how you choose to observe and to live, right? As an Indigenous storyteller who practices the art of non-fiction, in documentary film and also in writing, the greatest gift of this project was that it called me to live in a very present way with my family and my community. I returned to parts of my culture, my spiritual beliefs, and myself. I was living out on the East Coast when I started this project. I had a life working in politics, and all of that made me become more distant. There is something magical about the art of documentary, and particularly vérité. We spent 150 days in the field. I moved in with my dad for the two years of making this film. We had to live it.

POV: When is the community getting a chance to see it, and what is that going to be like?

EK: The Chief and council were the first to see it, and the participants of the film. We went to Williams Lake before Sundance and showed it to the key participants so that they could start to think about how to prepare the community for the release of the film. We’ll be going back to do a much broader showing of the film in the community, but we have already done so, and it was really wonderful.

JBNC: In order to take care of us before we went off and shared the film with the community and the world, they had a sweat for me and Em, and as well as Chief Willie and Dave, my cousin and basically the medicine man of the community. The way in which the Williams Lake First Nation has received the film, received us making the film, and also really taken care of us while we made it, has been beyond loving and generous. We feel so grateful that they trusted us and will continue to love and support us while we help share their story.