An historic moment has been reached in labour relations this fall in Canada’s factual TV industry, precisely at the moment when the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts (IATSE), the union behind entertainment production, succeeded in forcing a game-changing set of concessions in Hollywood. The class-action suit launched in October 2018 against Cineflix Productions by the lead litigant, screenwriter Anna Bourque, has been settled successfully and is bound for court approval in December 2021. This sorry tale (with, hopefully, a happy ending) shows us how gross disparities came to fester for over 20 years between scripted and factual content-making conditions.

In 1991 a mere handful of Canadian independent producers were creating drama and comedy series and the occasional feature film, often—though not always—under union contracts. The Directors Guild of Canada (DGC), the Writers Guild of Canada (WGC), the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists/Union des Artistes (ACTRA/UDA), the National Association of Broadcast Employees and Technicians (NABET), IATSE (Canada), and their Quebec district councils all protected crew wages and working conditions. Eventually, they would collectively devise new categories for producers and creators of low-budget productions to continue making work under contract.

By 2000 though, a whole new media sector expanded without any contract or protection— just the goodwill of independent producers. Factual and lifestyle series exploded, driven by the mid-’90s birth of specialty channels across North America and Europe. Many production companies formed and grew rich supplying to these channels (History, Food Network, Discovery Channel, HGTV, etc.). Work blossomed for mainly non-union directors, DOPs, editors, production managers, show runners, post-production and production assistant staff, and especially entry-level workers. It was a heady time of growth and on-the-fly training. If you were toiling making your passion project or trying to bag a calling-card grant for your first scripted or short doc, you could survive as a crewmember on one of these series for a long time.

In large part, this parallels my own professional biography. At that time, I was part of two meetings about workers’ rights in this environment. One involved the (late) legendary Allan King, who cared passionately about working conditions. As then-president of the DGC, King wanted to help us figure out what our rates and working conditions should be and whether they could be improved under a guild contract. This required the cooperation of producers and, in many ways, broadcasters, too, because it would have codified a different level of license fees to pay for it all. In spite of best efforts, nothing happened. Broadcasters had their pick of producers willing to do whatever it took to bag a deal and more than willing to block any attempt to “unionize” these shows. As any union organizer or historian will tell you, when you have an over-supply of labour, your power to negotiate flattens. It was the same with directors and other keys: if we asked for a fair wage, there was always another person willing to do it for less and for longer workdays, regardless of safety conditions.

The second and more disheartening attempt to get fairness in factual filmmaking was trying to push the WGC to protect writers and story editors working on these shows, whether we also wore showrunner hats or not (as I often did). It wasn’t that fees weren’t appropriate as much as it was about having such fees recognized and attached to credits and having a retirement plan with benefits. Alas, the WGC treated many of us as impudent and continued to make it difficult for producers to sign on. To this day, I don’t know of a single series that went full WGC. A whole generation of writers and story editors have thus been left without protection, credit, or retirement benefits.

The overall message was clear: creators of scripted content matter; factual creators and by extension, doc makers, do not. Is it the (mis)perception that making quality factual content is…just easier than scripted? It’s hard to say. But if so, it hardly warrants the near total contempt shown some 2000 or so unscripted workers.

By 2013, the Canadian Media Guild (CMG), which is a local arm of the CWA [Communication Workers of America] Canada, had heard enough and undertook the research and publication of a booklet in 2015 called Guide to Working in Canadian Factual TV Production. The Guide not only documented harassment and abuses of overtime, safety and wages, with no sick or major holiday pay, it also called out a clever ploy used by all producers: Treat everyone as a contractor so labour laws don’t apply. That these basics were fully recognized by the guilds and unions just put the lie to the ploy.

CMG, through its Fairness in Factual campaign, hoped that the Guide would put the industry on notice and embolden factual workers to safely demand fair pay and conditions. They also attempted to get at least one good “actor”/producer to stick their neck out and sign a template contract of “best practices.” It all proved fruitless. Enter veteran Anna Bourque, an award-winning writer and story editor of both scripted (Ready or Not, Twitch City, Zoboomafoo) and unscripted television and film. Precisely because of her experience writing scripted material under a WGC contract, she encountered a kind of cognitive dissonance: Why was it okay to have one set of rules for scripted, and basically no enforceable rules for unscripted? In 2016, Bourque and I worked together on a show at Cineflix (I left, she stayed, and yes, the hours were outrageous, as was the disparity in rates even amongst us). During that time, and on a follow up show at Cineflix, Bourque found it frustrating and punishing. “I tell everybody ‘Keep track of your hours,’” she told me recently, “but nobody does because they don’t think it means anything. People feel powerless.”

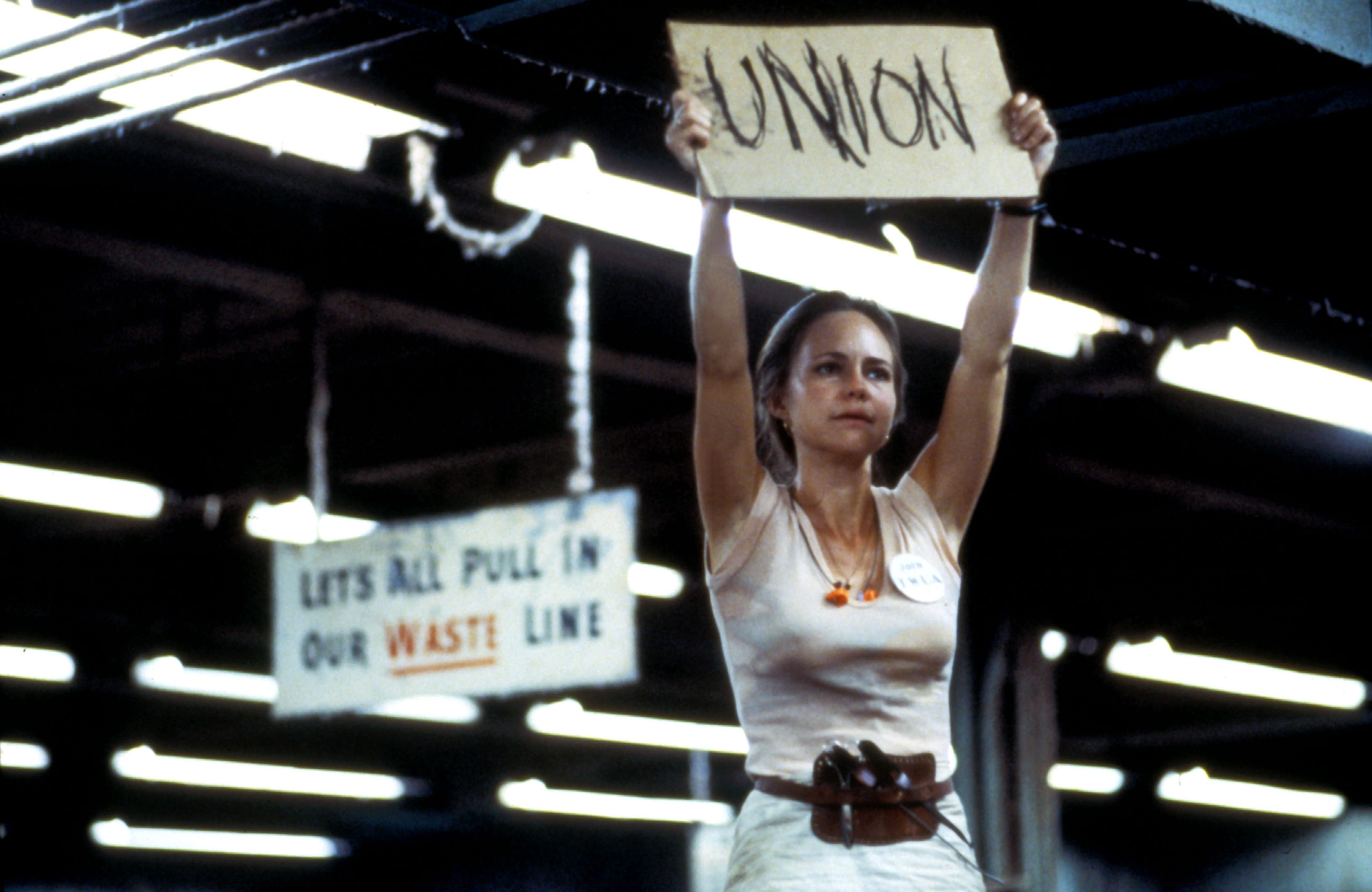

So, in 2018 Bourque set off a bomb. With the support of the CWA/CMG, she launched a suit against Cineflix, and then a second one against Insight Productions in 2019 (where she had subsequently worked) for the same grievances: unpaid overtime, sick and vacation pay. The goal? To not only get those wages for a whole class of former workers, but also to force a collective agreement. Bourque didn’t set out to be Norma Rae, but she says, “If you’re going to blow up your career, you might as well do it for a good reason!” She’s been blackballed by the factual industry in her hometown of Toronto ever since the suits were served.

“We make everything too well and we have a grovel culture,” notes Bourque. “We give broadcasters a great product that’s undervalued and we let them get away with it. They always ask for more and more, and if we have a collective agreement, then it forces producers to go back and say ‘no.’ So, it could actually end up being a benefit to these producers too.”

On December 21st, 2021, a judge will hopefully sign the settlement, which contains two pathways to resolution. $1,000,000 is to be paid if a fully ratified collective agreement is entered into between Cineflix and the CWA/SCA Canada and IATSE, or they walk away from the agreement, and pay out a higher chunk of $2.5 million in owed overtime wages, sick and vacation pay. The production company has until March 29, 2022, to decide. The settlement money would go to those who worked at Cineflix (some 700 plus have signed on as class members) since October 6, 2016, a date set by Ontario class-action law. If Cineflix does walk away, there’s still that second suit against Insight to settle.

Is the collective agreement the best agreement? “No, it’s a first one,” says Bourque. “If we can get more companies interested, then we have the beginnings of a groundswell. Remember, we all got into this business because we’re passionate about stories. It wasn’t to work crazy long hours. That just keeps it a young person’s game. A single person’s game. And that’s who I really did this for—the next generation who shouldn’t have to put up with what we did.”

Details on the collective agreement can be found here.

Correction (Dec. 7): A previous version of this article referred to the CMG as the Canadian arm of the Communication Workers of America (CWA) and not a local arm of the CWA Canada.

Update (Jan. 4, 2022): The settlement entered into between the plaintiff and Cineflix received court approval on Dec. 21, 2021.