Wandering through Sunil Gupta’s oeuvre, as one can do this spring at the Ryerson Image Centre, is an opportunity to meditate on how photography can simultaneously be a political act and a gesture of love and care. From the moment he took up the medium as a hobby earnestly, learning the trade through the dedicated Time-Life book collection and developing prints in his bathroom-turned-darkroom, it was paired with a growing sense of activist responsibility. A slender young Indian man, he had immigrated from New Delhi to Canada with his immediate family a few years prior, in 1969—“a month after Stonewall,” he likes to specify. The riots that galvanized gay liberation in North America resonated with him, as he would soon become increasingly involved with the movement in Montreal, through what he affectionately calls “Gay McGill.” The group, which often met informally at the apartment Gupta shared with his sister because of its proximity to campus, was a space to meet peers, talk openly, and organize.

An extended chosen family grew out of these connections, one in which the budding photographer trained his eye, snapping pictures of the quiet, joyous, radical moments that punctured their days: reading the papers, lounging, embracing, plunging in a pool with an inflatable penguin, marching. He published some of these images in the short-lived bilingual monthly newspaper Gay-Zette, making the domestic and the intimate public. He also captured evidence of the prevalent homophobic sentiments of the time: the non-descript façades of the bars where he and his peers could express their sexuality freely, as well as the tragic aftermath of the premeditated firebombing of the Aquarius bathhouse, where he worked, which killed three.

In this context, being visibly queer, whether through portraits that appeared in the pages of a magazine or on the streets, was a political act, an assertion of existence in a largely puritanical society that shunned what was seen as a deviation from heteronormativity. Gupta did both. “We would strut through downtown being noticeably gay to arouse people’s awareness,” he recalls with a smile, adding that despite the bigotry, it was a uniquely carefree and safe time in his life. “By moving from India to Canada, something very positive happened: I found myself. If I hadn’t migrated, I would never have discovered that it was possible to live as a gay man,” he muses.

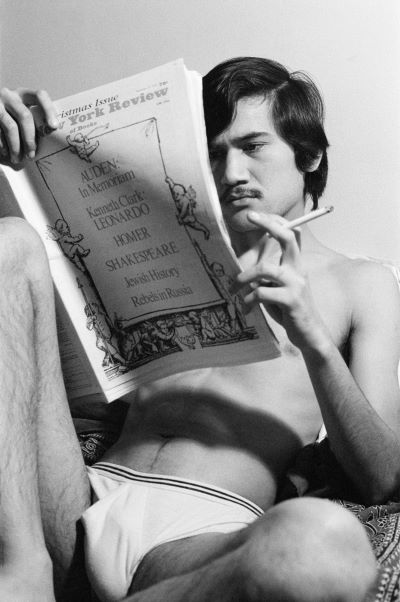

This process took shape in front of the camera, Gupta using it as a tool to explore his intersecting identities, the compromises, the tensions, and the opportunities that arose from them. There he is, in 1971, posing for an image reminiscent of a graduation memento, in a crisp shirt and sport coat, next to his equally well-dressed parents. There again, that same year, but this time sporting shorter hair and an army-green jacket. Gupta was hitchhiking back from the Valcartier military base, where, to appease his veteran father, he was training as a reserve sniper, though he was, like many of his generation, vehemently anti-war. There once more, three years later, sitting with four classmates in a management class, part of the business degree he was pursuing at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia), one of the few careers befitting of Indian progeny. We also see him raptly reading the Christmas 1974 issue of the New York Review of Books in white briefs, or repeatedly staring down the camera with a defiant gaze, at home in his body. He’s also seen laughing carelessly with friends or hanging out with his boyfriend, Rudi, whom he would soon follow to New York City. “My parents were slightly bemused and came to visit almost every day. I gave them a reading list to help them understand but I don’t think they took me up on it,” he writes, reminiscing about coming out in the early ’70s. “They thought it was a phase. But it wasn’t and I never came to live with them and I never got married and ‘settled down,’ in their eyes, as a proper Indian son. Instead, I followed my lover further and further away, first to New York and then to London, with the expanding gay family everywhere.”

Gupta would return to self-portraits later on, in 1999, creating six diptychs following and contending with his HIV-positive diagnosis, which left him feeling undesirable and, for the first time, ill at ease in his body. The series, titled “From Here to Eternity,” which the retrospective borrows, pairs images of the artist’s états d’âmes as he was battling a period of illness with the façades of shuttered gay club in the daytime. In one particularly poignant image, he is lying on his bed, a white shroud covering his body with only his feet and head sticking out at either hand. It is as if he is already dead, perhaps not clinically, but, in this instance, socially, given the widespread paranoia and lack of knowledge surrounding the disease. “For a brief moment, I was scared about sharing that part of my story, putting it up on the exhibition walls for all to see,” he confides. “But once it was, I felt immense relief. The guilt and the pain I had felt had been transposed into the image. The picture was now carrying it. And that’s what photography has also always been for me. From the moment I came out, it’s been a way of talking to the world.”

If Montreal was an awakening, Manhattan was a turning point. Enrolled in an MBA, which helped sell his mom and dad on the idea, Gupta quickly became engulfed in the photography world. “All the images that I had only seen in the books I studied, I could, all of a sudden, see in real life,” he recounts. “And there were 50 plus galleries dedicated to the medium, all welcoming with comfortable chairs and extensive libraries. You could just sit there and flip through the books or meet other enthusiasts.” Aside from a vibrant photography scene, New York was also home to a very public queer culture, especially in and around the West Village, with some artists bridging the two. Think Robert Mapplethorpe, Duane Michals, Arthur Tress, and Peter Hujar, all of whom comforted the then-23-year-old regarding the importance of photographing gay life. “Here was another perfect world that I stepped into,” he appreciates. By the second semester, he had dropped out of his business classes and signed up for courses at the New School of Social Research, where he got to study under, amongst others, Lisette Model.

Like his instructor, he took to the streets, and one in particular: Christopher Street, the main drag of gay New York, home of the Stonewall Inn. “For a period in the 1970s, the street was almost exclusively populated by gay men. For the first time in history, people like me felt able to live proudly, publicly, without shame,” Gupta later wrote in The Guardian. And he decided to broadcast his desire for men equally proudly, publicly, and without shame, by cruising the thoroughfare with his camera, capturing the likenesses of those he fancied: a pensive lad in a form-fitting black t-shirt with windswept hair, a debonair one with aviators shielding his eyes leaning with self-assurance on a metal railing, or a “college boy, a little scruffy, quite athletic, but with a gay edge that I loved.” If some return his longing gaze, others seem to pass by him with a calculated nonchalance. These fleeting photographic encounters became substitutes for the thrill of seducing someone; “almost as good as having had the sex,” the artist still likes to say. In this series, an act of desire, publicly avowed, becomes a political one.

Alex Espinoza, author of Cruising: An Intimate History of a Radical Pastime, highlights how the practice was an active rejection of the mores underpinning heteropatriarchy, noting, “It is devoid of the power dynamics that plague heterosexual interactions and exists outside of traditional hierarchies. True cruising allows people to set the terms of their own desire, and both leave satisfied. It is founded on equality.” Gupta’s record is even more salient given the tragedy that would soon follow. “Looking back on these images now, there’s a poignancy they never had at the time, almost like looking at photos of families before the Holocaust,” he further reflects in his commentary for the British publication. “A few years later, the AIDS crisis took hold. The public nature of gay life was forced back into the shadows. Thousands of men died. New York shut down its bathhouses, gay parties became private, and this whole world became hidden again.”

By then, Gupta was no longer in Manhattan, having followed Rudi across the Atlantic Ocean to London. His search for an accounting job unsuccessful and the need to secure a visa for his stay becoming urgent, he first enrolled in photography courses at the West Surrey College of Art and Design, followed by the Royal College of Art, from which he earned an MA. The schools introduced him to theory, particularly cultural studies, but without care for race or homosexuality. In fact, presenting gay work “became a problem,” he outlines in his PhD thesis (which he completed in 2018 at the University of Westminster) because “it was only a legal sexual preference for students over the age of 21 and as I was a mature student, I could get into legal trouble.” Neither the works of gay photographers or that of non-Western artists were mentioned, leaving a void that he quickly sought to fill, devising his own extra-curricular programme by seeking out the writings of the likes of Gayatri Spivak and Stuart Hall, as well as, for the first time, his fellow students of colour.

artist and Hales Gallery, London and New York; Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto; and Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi. © Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2022

“I was calling myself ‘Black’ in the postcolonial sense. Everyone who had been colonised by England was ‘Black’ and the enemy were the white institutions, especially the Tate, given its roots in the sugar and slave economy,” he explains. By the time he graduated, while art school had trained him for a commercial art practice, he had developed a disdain for the “right-wing bourgeois” art market. Instead, he renewed his commitment to activism and socially engaged art, getting involved in local town-hall politics and using photography to nurture rainbow coalitions. He taught workshops accessible to pupils from less-privileged backgrounds, contributed to the foundation of Autograph, an arts organization dedicated to championing Black photographic practices, and organized exhibitions designed to act as catalysts. Such was the case of Ecstatic Antibodies, which he curated alongside Tessa Boffin, a lesbian artist, to confront the mythologies held in Britain regarding HIV/AIDS. “The show toured, and each time it was hung, generated a lot of discussion in the media, which used it as an entry point to talk about AIDS,” remembers Gupta. “Frankly, it had a longer life as a trigger than most direct action.”

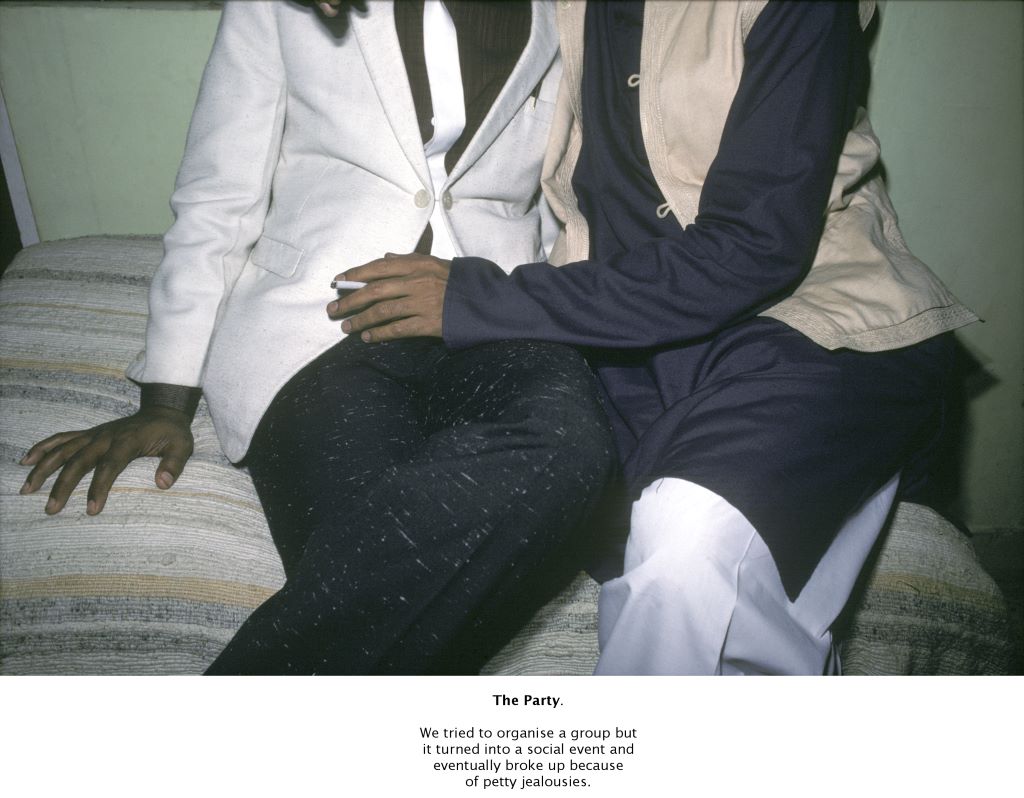

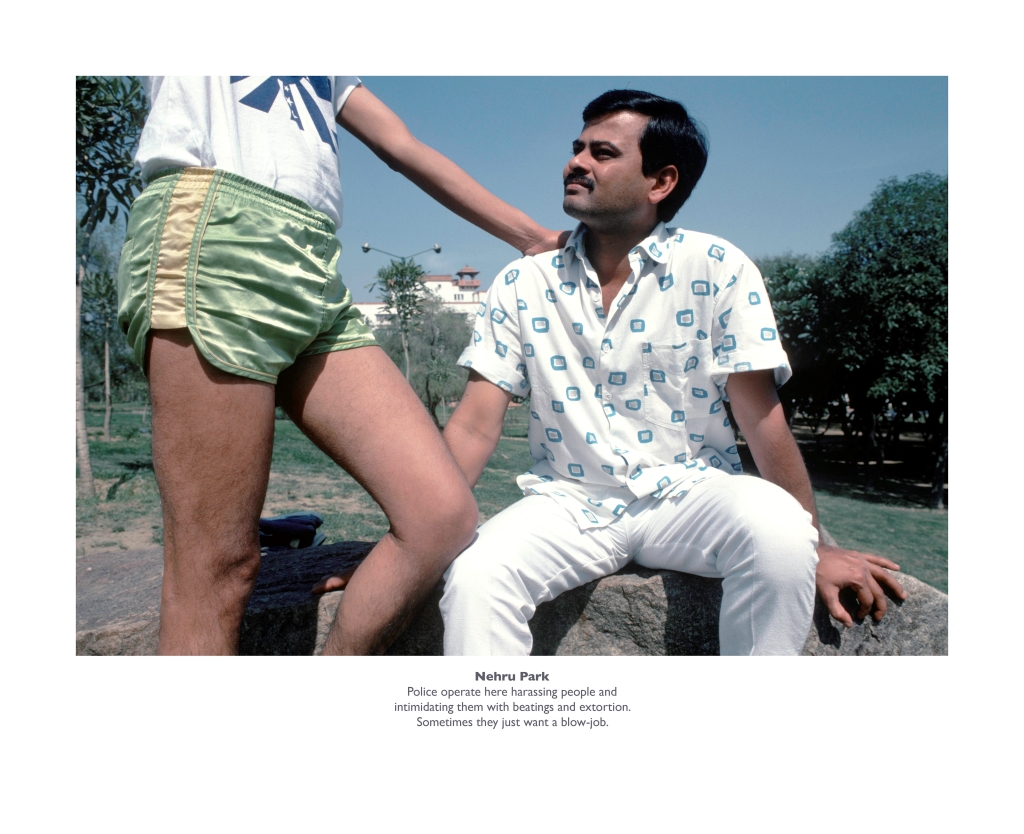

His own art became more overtly political, directly referencing and fighting the anti-gay policies enacted in the ’80s. At the time, in the midst of his education in the British academy, he felt the urgency of creating images of gay Indian men. “It had always seemed to me that art history seemed to stop at Greece and never properly dealt with gay issues from another place,” he observed. Given that homosexuality was punishable by law, Gupta turned to a photographic genre he refers to as “staged documentary,” posing those who volunteered in prominent sites around Delhi and working with them around issues of consent—careful to not “out” them. As a result, most are seen from the back or from the neck down, their touch suggesting their relationship. Below each is a caption that specifies the location, and a few lines gleaned from conversations he had with his peers during the making of the project.

A superb photo features two well-dressed men, one in a crisp, white suit jacket, the other in shalwar kameez, caught in an embrace or an intimate conversation, recounts the personal challenges of convening a recurrent social event in the face of “petty jealousies.” Another, featuring a man in a short, silky, green shirt resting his hand on his partner’s shoulders at Nehru Park, speaks of the broader social context wherein gay men are harassed by police, “intimidating them with beatings and extortions. Sometimes they just want a blow-job.” The series, titled Exiles, is telling of both the private anxieties and public adversity the men shared, subtly intimating how the two are entangled.

Gupta quickly reprised this strategy for ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships a couple of years later, this time in the British context. The series was created as a direct response to Margaret Thatcher’s introduction of Clause 28, which stipulated that local authorities “shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality,” or “promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.” Passed in 1988, and only repealed in 2003, the law had far-reaching implications, including on arts funding and education, involving some of the programming that Gupta and his peers ran. In defiance, he created large panels combining a colour portrait of a fictional homosexual relationship with poetry by his then-new partner Stephen Dodd and a crop of a black-and-white photo taken at a protest staged against the law. Whether in India or in London, pairing portraits of visibly gay couples with text allowed the artist to show how inextricably tied the domestic, the intimate, and the political are. That one cannot be uncoupled from the other.

Similarly, 20 years later, in the early aughts, he took up Section 377 of the British colonial penal code, then still in effect in India, which criminalizes “carnal intercourse against the order of nature.” This time around, he had Indian queer folks look straight into the camera, ready to be identified, claiming their identity. The title references the Delhi party scene, where gay nights at local clubs were advertised as private parties using a fictitious person’s name. “Attending one such night out, I noticed that the party was being hosted by a ‘Mr. Malhotra,’ and the reason why it seemed so out of place was that it was such a common name, one that conjured up the hard-working Punjabi families that had arrived after Partition and that had made Delhi what it is now,” reflects Gupta. So much so, in fact, that one such Mr. Malhotra, who was Additional Solicitor General, declared in those days: “Homosexuality is a social vice and the state has the power to contain it.” Ten years later, it would be another Malhotra, this time a woman, Indu Malhotra, that would strike down the law, as part of the unanimous Supreme Court judgement that found Section 377 to be unconstitutional. At the same time and in the same spirit, he also made a set of studio images referencing the art of the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood known for its romanticism, classical poses, and commitment to study the truth of Nature intently. In Gupta’s rendition, commissioned by Mark Sealy, the curator of the retrospective, the “truth of Nature” is represented by homosexual individuals posed in vibrant and colourful settings.

Whether in Montreal, New York, London, or Delhi, Gupta is attuned to the politics of visibility, and, as his career attests, to the many ways photography can contribute. “As an artist, you are able to insert your visual material into a conversation,” he sums up, “and, by the same token, turn it into a vehicle for greater discussion.”

From Here to Eternity. Sunil Gupta, A Retrospective runs until August 6 in the Main Gallery at Ryerson Image Centre. It is curated by Mark Sealy.