Every time May approaches, I eagerly await not only the cherry blossoms in nearby High Park, but also the changing of the images displayed on billboards around my neighbourhood. For a few weeks, rather than an ad for, say, the latest meal prep service, I get to enjoy art, courtesy of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. In 2018, I merely had to step out onto my building’s fire escape to stare at Kent Monkman’s delightfully provocative work featuring his two-spirit alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. A few years earlier, during my first spring in the city, all I had to do was take a walk along my street to appreciate the equally alluring and subversive images of Dana Claxton, including a candy-coloured bison, and other emblems of colonial imagery that she had digitally altered. Both artists urge us to reconsider our relationship with iconography, how it has been used to stereotype, reduce and erase Indigenous lives and culture. Not your standard advertising billboard experience! In fact, the support itself plays deeply into the messaging since both also consider the commercialization of their traditions—Monkman is Cree and Claxton is Lakota.

Since 2003, CONTACT has been organizing a substantial public art program, taking over not only billboards but also a host of other city spaces: national historic sites, subway stations, concourses, building façades, and the like. In its early days, the festival, which launched in 1997, functioned almost exclusively as an umbrella and educational organization, guiding gallery-goers through different sites so that they could experience the richness of the photographic arts. It did not have venues where the coordinating team could stage their own curated shows. Bonnie Rubenstein, who became artistic director in 2002, knew that her background in site-specific installations in non-conventional spaces pointed the way forward. She enlisted the help of renowned Canadian and international artists Ken Lum, Robyn Collier, Catherine Yass, and Jamal Shabazz in developing a public art project and securing additional funding. From then on, the initiative grew, serving dual purposes. On the one hand, it creates new opportunities to design singular exhibitions that enter into a dialogue with their locale and activate public space. On the other hand, it also functions as a form of marketing, creating awareness of the event and expanding its reach to audiences who don’t usually frequent the proverbial white cube. In short, it’s a way of occupying the city even more.

This year, more than ever, CONTACT’s outdoor programming is taking centre stage. Even though I’m always excited for springtime to arrive, I’m just that much more impatient this time around. Last May, little by little, strips of ads weathered away, resulting in an accidental collage. Eventually, on some of these unsold advertising spaces, reproductions of natural landscapes appeared. In the midst of the pandemic, both the view of a moose crossing a river and of an ocean from inside a cave were somewhat soothing and symbolic. As commercial and industrial activities were slowing down, nature was already taking over some of the structures they were forsaking. Still, when I looked into it and learned that they were the compositions of Herman Bekkering, the national creative director of Pattison Outdoor Advertising, I felt a little cheated. Couldn’t they have used this opportunity to feature works from various artists who have developed an intentional practice of interrogating society and the present moment, and who, given the cancellation of most if not all shows, were looking for alternative ways to share their reflections? It is true, of course, that Pattison sponsors the CONTACT festival’s billboards each year, but here was an opportunity for them to extend their engagement with the arts beyond their annual commitment.

Last year, I was particularly looking forward to encountering the work of Małgorzata Stankiewicz during my regular city wanderings. The Polish artist was scheduled to have her series Lassen (This Is An Emergency) appear on billboards in 2020, but, because of the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic, it was moved to this year. In the meantime, the display format has evolved. They will now be pasted as a grid of posters at various street-level sites throughout Toronto. Her project confronts the paradigmatic depictions of the Anthropocene. Rather than present evidence of humans’ colossal impact on the planet using an aesthetic that often veers on the sublime, she creates images that are anxiety-inducing. The landscapes they depict, following a number of darkroom experiments, appear to be burning, melting, disintegrating. She thus suggests how our world, and our memories of it, are concurrently vanishing. Their resonance is magnified after months during which we’ve witnessed apocalyptic wildfires in Australia and the United States and intensifying hurricanes, cyclones, and storm seasons. Over the year, we’ve worried about the dwindling ice in the Arctic, studied the correlation between air pollution and rates of COVID-19 infections and watched land and water protectors being harassed by authorities.

The events of the past year have also brought increasing attention to our public spaces. We simultaneously need them to maintain our health and sanity, and come to fear them as sites where diseases spread. Beyond the billboard takeover, a number of the more involved public installations featured in the 2021 edition of CONTACT provide insights on how to approach and navigate this tension.

Esmaa Mohamoud’s project The Brotherhood FUBU (For Us, By Us), for instance, reminds those of us for whom being uneasy in public spaces is a new feeling, that such carelessness is a sign of our privilege as well as the pervasiveness of gender and racial dynamics. Displayed as a larger-than-life print on the west façade of the Westin Harbour Castle Conference Centre right by the water on Queen’s Quay, the image of two Black men connected by a two-headed durag standing in Lake Ontario confronts where and how we expect to see Blackness represented. “I’ve been trying to imagine Black bodies in Canadian landscapes in non-laborious positions for quite some time now,” says the artist who, with this piece, endeavoured to reinsert them in both the pastoral and urban settings from which they’ve historically been, and continue to be, excluded. Photographing in the water was a necessity, a way to recall the “secrets it holds and the tales of Black lives and diaspora,” while the downtown placement serves to initiate a conversation with the Canadian public writ large about “the constant criminalization of young Black men.” Still, the ensemble is mainly intended for her peers, especially the budding generation. “I didn’t make this for anyone but for the Black community,” she admits. “I hope it can foster a sense of confidence for Black children to see themselves celebrated at that scale and in that space.” Indeed, the sheer size of the mural—37 by 144 feet—and its positioning above street level shifts the usual power script that exists in art, as well as in society. The two men are the ones gazing, inquisitively and skeptically, at the passersby, their presence undeniable.

Nearby at the Harbour Square Park, an accompanying sculpture, a bronze rendition of the two-headed du rag, will eventually be installed, as part of the partnership with ArtworxTO: Toronto’s Year of Public Art 2021, which has seen some delays because of the pandemic. It comes at a time where commemorative effigies have come under increased scrutiny for the oppressive legacy they embody. “When I’m on University Street in Toronto, I don’t see myself reflected,” says Mohamoud. “The statues and monuments that line the road are outdated and out of touch. They don’t sit right.” Rather than propose a substitute figure, she’s more interested in considering the symbolic power of objects, how we relate and interact with them. The durag here becomes a stand-in for her community, its strength, diversity—one side features a relief of cornrows, the other one that of wavy hair—and connectedness. As a whole, the commission, which will be up for two years, is an act of reclamation of space both, to paraphrase Mohamoud, within our actual, physical landscape and our cultural one.

A similar undertaking is underway at Fort York, a symbol of British imperialism. Having already invested it for the 2019 Nuit Blanche with a collective multimedia project entitled Listen to the Land that countered the location’s long-standing colonial dominance by calling forth the Indigenous presence it buried, artist and curator Logan MacDonald was initially hesitant to return. But his familiarity with the space presented an opportunity to challenge it in different ways while simultaneously reaffirming important critiques. “This particular site upholds a violent colonial narrative that establishes a basis for claims of Canadian sovereignty and national identity,” he explains, “yet this is also within the Dish with One Spoon Wampum landscape, a known trade route, a place of collaboration. So why is it that we don’t use this public space, or any really, to uphold different kinds of narratives? For instance, as opposed to a site of violence, can’t we also suppose that it once was one of pleasure?”

To enact his counternarrative, he brought together the works of four queer Indigenous artists for an exhibition entitled Force Field. Peter Morin, Dayna Danger, Fallon Simard, and Ange Loft’s distinctive art practices address the intersecting impacts of settler colonialism on lands, bodies, and stories, and work wonderfully well together. Their projects will be displayed inside a circular structure divided into quadrants inspired by the medicine wheel. Each artist is responding to various degrees to the natural element—earth, fire, air, water—that they have been assigned by assembling a collection of images from their archives. The outside will unify scenic panoramas that feature a strong dividing line, a means to disrupt the city horizon by inserting a new one, thus compelling us to see past our own parochialism. The intervention is also designed in such a way that it invites contemplation. Unlike Mohamoud’s piece, it is unlikely to surprise you and stop you in your tracks as you stroll downtown. In lieu, you must make a much more conscious effort to enter both the historic site and the installation. “Public presentation is often about quick consumption,” notes MacDonald, who instead strived to play into the solemnity of the site to create a space where there’s some level of privacy allowing deeper reflection. He hopes that this collaboration will bring people, visitors, and institutional partners alike to “reevaluate the protocols around what is being nurtured in our public spaces.”

Such transformational work is seldom accomplished in one fell swoop. Rarely does a single site-specific installation upend the historical and institutional representations that have become embodied in a place. Herein lies another tension for temporary public art, especially when it directly addresses how systemic oppression manifests in our public spaces. What happens to the location’s narrative once the artistic provocation is removed? “Susan Blight and Hayden King’s Ogimaa Mikana renaming project, which restores the Anishinaabemowin place-names to the streets, avenues, roads, paths, and trails of the city, is impactful because of their potential permanence,” believes MacDonald who considered how to deepen the ramifications of his intervention. On the one hand, one aspect of Force Field will remain: the medicine garden that is being planted at the heart of the structure will endure. This additional, living module extends MacDonald’s larger inquiry into how maintaining Eurocentric manicured park spaces doesn’t allow for Indigenous or even queer engagement and constitutes a form of erasure. On the other hand, he acknowledges that he is part of a continuum, building on previous interventions and to be followed by the contributions of peers and colleagues. “Even though this may be the last time I engage with that space, I hope that what I’ve done with Placeholders for Nuit Blanche and with this group show for CONTACT creates momentum that others will carry forward,” he muses.

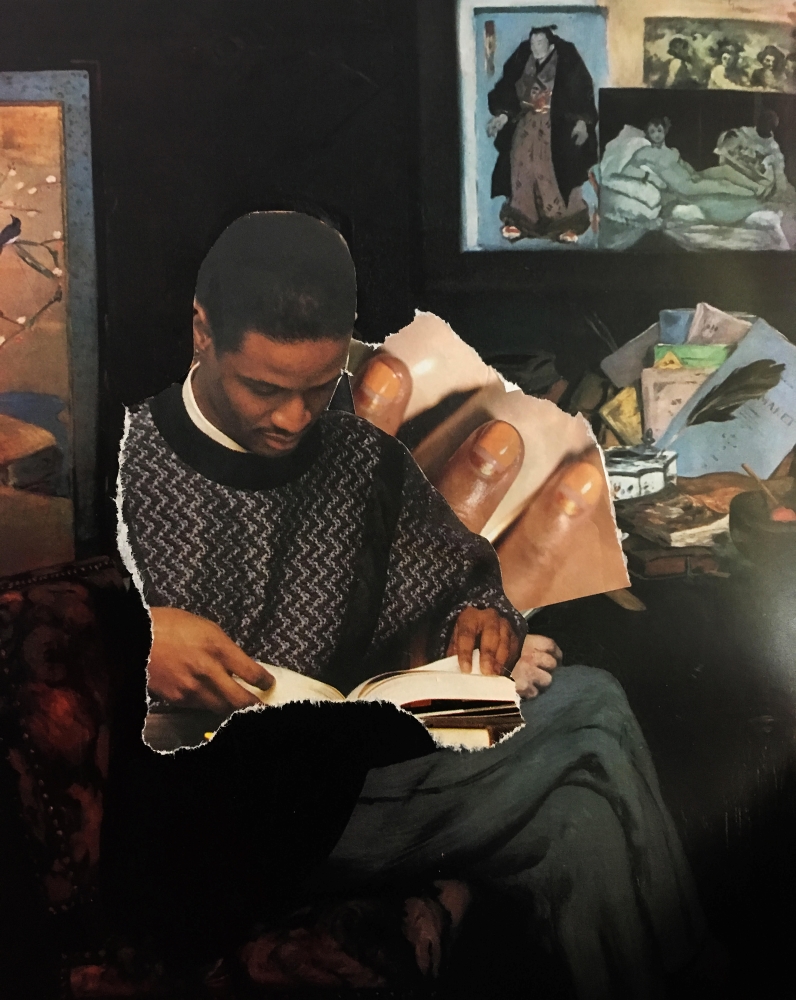

Viewers also carry a responsibility to engage and connect the works that are being so generously offered to us in our daily space. We should pause at the base of Mohamoud’s mural, welcome the discomfort of being looked at and conjure the memories of series by Jalani Morgan, John Edmonds, and Carrie Mae Weems that have previously been displayed during the festival at Metro Hall. MacDonald’s projects converse with those I’ve encountered in past years, such as Claxton’s and Monkman’s billboards. Transforming our public spaces into those we dream of for our future is an ongoing and collective endeavour.