The designation of “essential” individuals and work in response to the COVID-19 pandemic revealed a lot about who we value and who we overlook within our societies. The standing of doctors, already everyday heroes for saving lives and curing diseases, was further elevated. Significantly, we were finally forced to acknowledge the importance of grocery clerks, transit operators, and other labourers who are so often disregarded because their toil is usually seen as menial. On the other side of the coin, COVID-19’s toll in longterm care facilities prompted discussion about the expendability of older citizens, a line of thinking that peaked when the Lieutenant Governor of Texas, Dan Patrick, suggested that Americans over 70 years old should be willing to sacrifice themselves in order for the country’s economic activity to resume.

Watching these debates play out, a question emerged about the role of both visual artists and journalists. An early meme stated: “If you think artists are useless, try to spend your quarantine without music, books, poems, movies, paintings, and games.” Access to substantiated and accurate information proved so crucial that newspapers made sure that their coverage of the pandemic was available for free online. In Canada, the federal government listed “workers who support radio, television, and media service, including, but not limited to front line news reporters, studio, and technicians for news gathering and reporting” within their list of essential services and functions. That being said, upon reflection, media workers’ “essential” designation should not be read as a pass to continue business as usual. Rather, it’s an invitation to consider exactly what part of being storytellers and media-makers is indispensable and how we fulfill those responsibilities safely and respectfully.

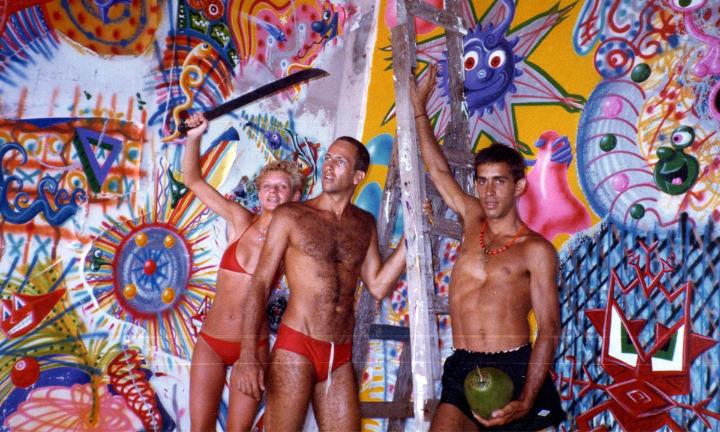

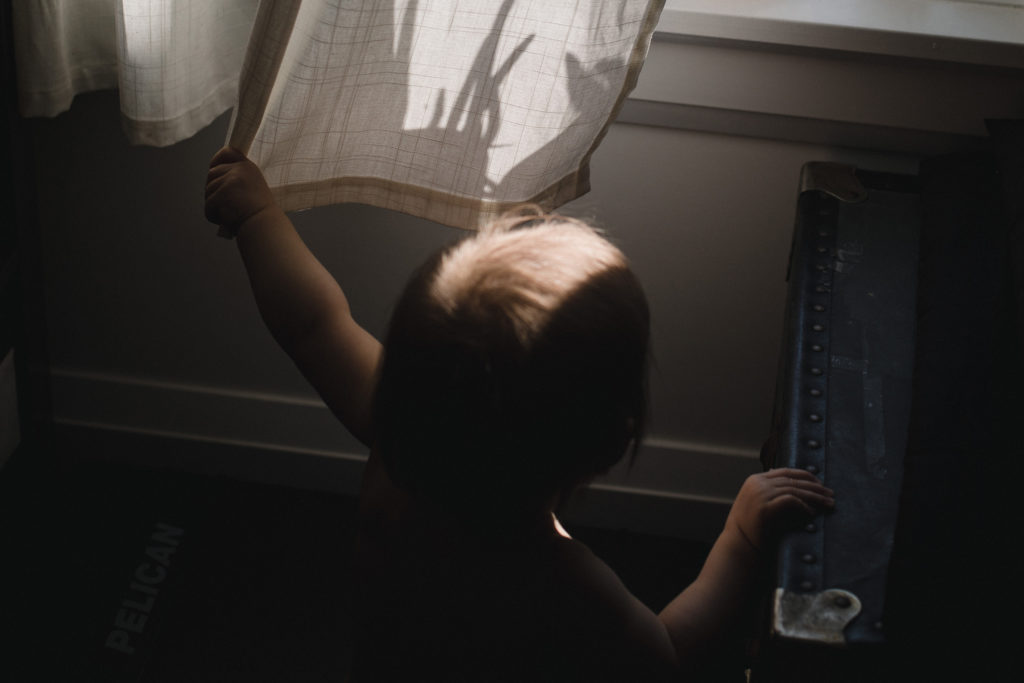

This image was shot as part of my ongoing project, Puberty – a self-portrait project which looks at the intimate and vital process of self-care as a non-binary transgender person undergoing hormonal replacement therapy (HRT). Shot over a period of two years, it combines surreal colours and mundane environments to document daily moments and slow, subtle physical changes occurring during my transition. Looking at HRT as a process without a fixed end goal, Puberty challenges viewers to consider identity beyond binaries. | Laurence Philomene

In the first few weeks of the pandemic, photojournalist Renaud Philippe began a road trip across the country to offer a personal outlook on this historical moment. By his own admission, in an interview he gave to Le Devoir, the Quebec newspaper that published his black-and-white images, his intention was not to replicate the styles of the press photographers who live and work within each community from Quebec City to Vancouver but to develop a distinctive vision. The project immediately raised red flags and sparked criticism. Was it sound and necessary to undertake such a journey at a time when remote towns such as Thunder Bay were asking people from major cities to avoid visiting? What precautionary measures could mitigate the risks that traveling from province to province poses to both the photographer and those they encounter? I raised these questions then, and feel compelled to raise them again, as many colleagues continue to grapple with how to ensure that they practice their craft responsibly. How do we provide important information about a global health crisis and coverage of a unique historical moment without putting lives at risks?

While Philippe was on the road, I joined a training session led by Dr. Jenell Stewart (Master of Public Health), an infectious diseases physician-scientist at the University of Washington, who put together a COVID-19 guide for visual journalists. She instructed us on how to assess risks. Assignments that involved being indoors with anyone who hadn’t been following strict social distancing measures or who might have been exposed to the virus were high risk. Journalistic or photographic work which could be fulfilled outside and that didn’t require setting down gear or getting close to anyone were on the lower end of the spectrum. Dr. Stewart stressed that no assignments were entirely safe. She enjoined us to create a “hot zone” at home—a space by the entrance in which to decontaminate everything, clothes and gear included—before proceeding to our daily domestic activities. Given how quickly the virus was spreading in April and the need to ensure that hospitals would not be overwhelmed, she strongly advised against travel of any kind. These recommendations have since evolved to reflect changing realities and policies.

Pat Kane, a photographer in Yellowknife, took such advice to heart. Wanting to keep risk at a minimum while also reflecting on the pandemic situation in the North, he began taking pictures of his neighbours through their windows. “The circumstances here are very different than in the South,” he explained. “While we’ve had a total of only five cases [as of press time in November 2020], we understand just how devastating it would be if the numbers had been higher. We have one hospital for the whole territory, which many people would have to be taken to by flight, and there are language barriers for some of the Indigenous elders.” As a result, residents were quick to abide by the health guidelines. Kane saw an opportunity to comment on the changing social relationships in a region known for being tight-knit as well as showcasing how people live in that part of Canada. Hence, his photographs focus as much on the families as they do on their homes. “It’s a way to talk about life up here,” he summarizes.

Kane wrapped up the project after making a hundred images. On the one hand, it felt like it had accomplished what he had set out to do, especially having been published in several Canadian and international publications. On the other hand, the Professional Photographers of Canada (PPOC), a non-profit representing the interests and rights of about a thousand accredited members, reached out to voice their concerns about the new fad of “porch portraits”—family sessions on their front steps, balconies, stoop, etc.—which was taking hold from coast to coast. “As a national organization we recognized that the policies differed depending on the jurisdiction, but the overwhelming message from public health authorities across the country in late March was that we needed to stay home, and only leave if absolutely necessary. I can’t think of any reason at that time why taking family portraits would be essential,” declares Ross Outerbridge, the BC member of the association’s National Board of Directors and a physician. “Sure it was a beautiful idea. It just wasn’t the right time.” What was needed, believed the organization, were unequivocal and strict guidelines to avoid confusion.

“I was conflicted,” admits Kane about PPOC’s stand. “While I understand their position and the need for containing that trend, I’m not sure a full out ban was necessary. Many photographers were acting in a safe manner, using zoom lenses to keep their distance, keeping a window as a barrier between them and their sitters, etc. It wasn’t my only reason for stepping down, but I factored it in. I wanted to be respectful. Yes, photography is essential but when it gets to a point where we’re putting others at risk because of our own pursuit, then it is time to reflect and rethink our practice.”

Kane was far from the only one to reevaluate their habits. Unwilling to endanger lives by traveling, many turned to collaborations and crowdsourcing. Projects range from George Pimentel’s Canada COVID Portrait, which features photography from amateurs and professionals alike who have captured how the pandemic is transforming our communities, to Natalia Dolan’s “In My View,” a collection of window views from around the world. One of the most ambitious was The Journal, an initiative by Charlotte Schmitz out of Berlin, with the support of her colleague Hannah Yoon, a Korean-Canadian photographer now based in Philadelphia. At its height, over 350 women photographers from 80 different countries, mostly independent contractors, participated, exchanging ideas, imagining collective series within smaller groups, and sharing their work. One group, composed of documentarians in Canada, Chile, Mexico, and the United States, created a visual chain letter inspired by historic images from the 1918 pandemic flu. The effort, believes Yoon, “challenges perception of what it means to be a freelance photographer. You don’t have to be a lone wolf only looking out for yourself.” Simultaneously, given the intimate nature of the photographs shared, it offered another perspective on the beginning of the early days of lockdown measures.

View this post on Instagram

“While newspapers were focusing on what was happening on the frontlines and in hospitals, we featured, on our Instagram account, images that spoke of interpersonal hardships, of caretaking, of domestic lives, of loneliness, and so on,” notes Yoon. That caught the attention of major news outlets, which republished some of them, further legitimating the collective vision championed by Yoon and Schmitz.

Another formidable collective effort sought not to create new work, but to set standards for the industry. Seventeen photographers, affiliated with grassroots organizations like the Authority Collective, Positive, Women Photograph, and Natives Photograph that have been advocating for change in visual journalism and editorial media practices, came together to author the Photo Bill of Rights (PBoR). What began with an open letter about the vulnerability and precarity of lens-based workers during the pandemic, morphed into a comprehensive document that discusses pervasive issues surrounding health, safety, access, bias, ethics, and finance. It calls for establishing hazard pay, kill fees, and timely compensation schedules. It demands the creation of safe protocols to address allegations of all forms of abuse and sexual misconduct, to which photographers from marginalized communities are disproportionately exposed, as well as codes of conduct to confront implicit bias and support equitable access to opportunities.

Protests in Los Angeles have moved from police clashes to a more celebratory tenor in the last week.

Photo by Tara Pixley

To illustrate how these issues intersect, Tara Pixley, a visual journalist, strategic storytelling consultant, and professor based in Los Angeles, who contributed to the PBoR, considers the delayed payment practice: “When you wait 60 days to pay photographers, you’re pricing out those who don’t have a financial safety net. That’s why the industry looks the way it does. The people that have institutional and generational wealth are the ones who can afford to stay.”

In highlighting these disparities, the PBoR also seeks to confront the continued prevalence of the white, Western, cisgender, colonial male gaze. “Documentary photography’s history is deeply imbricated with the history of colonialism and the dehumanizing processes that set the stage for chattel slavery and various world genocides. Images intended to categorize and catalogue the faces and bodies of brown and Black people from India to the indigenous population of the Americas were used to underscore Othering narratives,” wrote Pixley in a recent article for PhotoVoice, a UK based charity. “Today, documentary images and, by extension, photojournalism as a practice, are still imbued with the residue of these racist, imperial tactics.” The examples abound, amongst which is the notion of consent.

Photojournalists have long held dear the idea that their benevolent and essential mission to shed light in the dark corners of the world—to use an oft-repeated and dated, though telling, cliché— was enough to sanction the invasion of people’s privacy and disregard their right to self-determination. While these concerns have been raised multiple times before, especially in regard to how tragedies that happen abroad and at home receive different visual treatments, they became increasingly salient over the summer as protests against police brutality and the state-sanctioned killing of Black and Indigenous people took hold around the world. Alarmed by the possibility that images taken at marches, rallies, and sit-ins would be used by the authorities to identify and prosecute participants—which did happen—members of the photojournalism community, including the instigators of PBoR, called for normalizing informed consent as practice, namely the need to obtain the explicit permission of capturing anyone’s likeness, having told them about how it might be used and where it might appear.

This provision, included as a “Beyond the Bill” chapter, was considerably expanded because of the hostile response it garnered, and in reaction to the questions that were raised regarding the practice of photographing sex workers, including minors, by the likes of David Alan Harvey and Txema Salvans. “We have been eager to shift conversations of consent past discussions of simply what is legal, and more towards our role and foundational tenet as journalists, to do no harm,” explains Laura Saunders, a photographer and filmmaker working in southwest Virginia and southern Arizona who also contributed to the bill. “It has been used as a reason to outright dismiss the entire document and take the conversation away from what the objective was, which was to discuss systemic injustice.” Pixley adds that she was shocked by how many of her colleagues were willing to flagrantly display their lack of regard for the lives and safety of people they are photographing. “What I find both confusing and horrifying is that those who came after the PBoR are the same ones who sit at the ready to run into battle to fight the good fight by documenting the world’s worst ills,” she says. “They talk so convincingly about the instrumental role photojournalism plays in bringing human rights issues to the forefront, yet they dismiss similar concerns when it involves looking at our industry and practices. Watching that play out as we were putting the final touches on PBoR, was very vindicating.”

Public conversations regarding what is and isn’t essential reporting, the responsibilities of visual journalists, and the legacy of photography’s history as a tool of imperialism are overdue and necessary if we hope to build a rich and diverse media ecosystem that is reflective of our contemporary societies and reflects its multifaceted realities. These will not be easy discussions, nor will they be quickly resolved. In September, Le Devoir announced a new three-week road trip series, this time in the United States. Reporter Sarah Champagne and photographer Valerian Mazataud were to create a portrait of the country on the eve of a critical election. The border between Canada and our southern neighbour remains closed to non-essential travel. Transmission of the coronavirus from region-to-region continues to be a concern, especially as the risk of a second wave looms. Yet a Canadian perspective on this pivotal moment is not without value.

So how do we reconcile these tensions? Where and how do we draw the line? “One of the beautiful by-products of the Photo Bill of Rights and this moment,” believes Saunders, “is that it’s exposed photojournalism for what it is: an industry, as much as it is a community.” Now comes the time to shift our focus to the latter, and ensure that its future is grounded in care, respect and equity.