Black Drones in the Hive, which was on view at The Image Centre in fall 2023, is an offering to the public, bestowed by artist Deanna Bowen, winner of the 2021 Scotiabank Photography Award, and curator Crystal Mowry, who first mounted the show at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery (KWAG) in 2021. As an offering, a provocatively assembled gathering of found objects, it also comes with an appeal: that we thoroughly engage with its teachings and carry them forward.

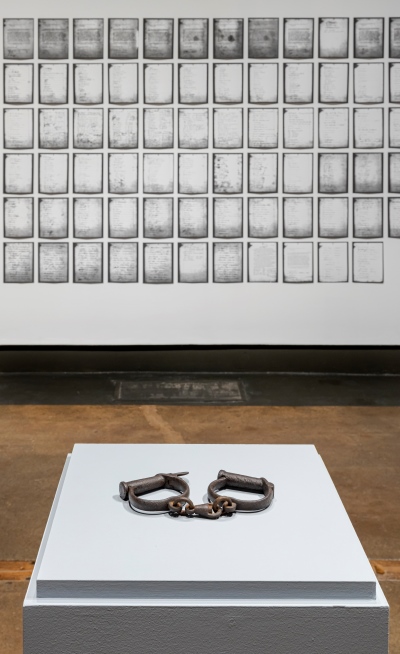

An empty plinth, paintings from the Group of Seven, an anti-immigration petition, commemorative Uncle Tom’s Cabin plates, abolitionist coins, articles, photos, maps, etchings, and many more objects; it might all seem, at first glance, an eclectic collection. As the threads between them become clearer through intense viewing, it provides evidence of the pervasiveness of settler colonialism, white supremacy, and Black erasure, as well as making manifest the mechanisms through which these oppressive structures have sustained themselves through time. The assemblage turns overwhelming, given, as Bowen puts it, “what it says about how people were so unwanted that they were so callously destroyed.”

Bowen works from the premise that we, her audience, are equally capable of grasping the myriad connections and meanings that the constellations of archival materials she has gathered and carefully organized expose. “If you can read a painting,” believes the artist, “you can read what I’m putting in front of you.” Especially given that the materials she works with were created by and for white folks. “This is not new information. I’m working with documents that people have likely seen before, that are legible and true. All I’m doing is rearranging them in a way that is slightly off-kilter and in relationship to one another,” she adds.

Take a section of the exhibit dedicated to eugenics. It is made up of eight frames, arranged in two rows. At the centre, a copy of a “Eugenical Classification of the Human Stock,” listing at the top “persons of genius,” who are those “most splendidly equipped by nature.” The examples are all names that we continue to recognize, for they are held as paragons of achievement in their respective fields: Raphael and Rembrandt for painting; Marco Polo and Columbus for discovery; Richelieu and Queen Elizabeth I for statecraft. At the lowest rung of the hierarchy, the “socially inadequate,” a category rife with ableism. And in between the “persons of special skill,” followed by those “constituting the great nominal middle class.” Lest there be any misunderstanding, the mandate of eugenics is clearly laid out at the bottom of the page: “a) to encourage fit and fertile matings [sic] among those persons richly endowed by nature and b) to devise practical means for cutting off the inheritance lines of natural meagre or defective inheritance.” The document is so explicit that it stands as a testament not only of the ideals of white purity put forth by eugenics, but also of its social acceptability—there was no need to conceal its purpose—so much so that the ideology kindled humour.

Just look to the right of the taxonomy, where Bowen has placed the June 18, 1913 cover of Puck Magazine, for further proof. It depicts a doctor turning the world on his feet with the caption “Eugenics Makes the World Go Round,” without much concern for how it impacts lives. This is contrasted by the document that stands to the left of the classification: a reproduction of “the portraits of Two Will Wests.” The style will be familiar to all as the profile and frontal view that have come to typify mugshots and are an essential part of the Bertillon system of identification. Developed in 1879, it relied on precise measurement of physical characteristics to index suspects and criminals. The appearance of this record here encourages reflections on policing methods and their white supremacist lineage. Bertillon’s anthropometry informed the eugenics movement’s discriminatory correlation between physical traits, intellectual abilities and worth. And while it was eventually replaced by an onus on fingerprints as unique identifying markers, thanks in part to the incident of the two Will Wests referenced here—two men of the same name shared similar features, creating confusion at the time of their incarceration—parts of what has been christened “bertillonage” continues to pervade our justice apparatus through mugshots. The decision to display the police’s files of the doppelgangers as negatives suggests that we contemplate the white gaze as an instrument of codification and criminalization, rather than focus on distinguishing the physical characteristics of the depicted individuals.

I could continue to describe and untangle each element that makes up Bowen’s arrangement. How a portrait of Queen Victoria juxtaposed with a story about a painting of the late Kaiser Wilhelm I speak to the kinship between the British and German royal families and their colonial impulses. How the pages from a poetry anthology titled “Songs of the Great Dominion,” featuring works by Duncan Campbell Scott, a celebrated Canadian literary figure despite being the architect of the residential school system, and by the lesser-known E. Pauline Johnson, a Mohawk writer, bring up questions about the national narratives that are valued and why. And so on. I could link those with documents shown in other constellations in the show such as those pertaining to the Kaufman Rubber Factory, established in Kitchener-Waterloo, then called Berlin, which highlight the owner’s predilection for the forced sterilization of his working staff. Yet that associative work is most meaningful when done by each of us, as it is both an instructive and introspective endeavour. “I hope this show acts as a catalyst,” says Bowen, likening it to a manual dedicated to how both individuals and institutions should approach archives: with curiosity, expansiveness and, crucially, criticality.

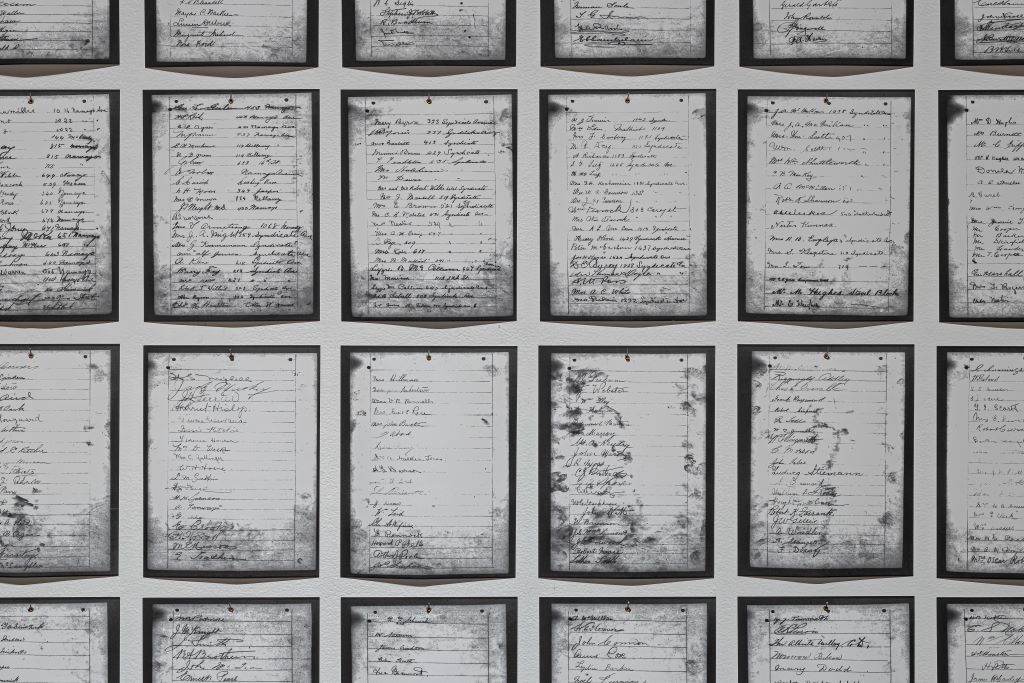

Black Drones in the Hive builds on Bowen’s previous works, especially the display in the collective exhibition Carry Forward, curated by Lisa Myers at the KWAG, of the “1911 Anti Creek-Negro Petition.” The 233-page document called on Sir Wilfred Laurier, then Prime Minister of Canada, to prohibit the immigration of Black people from the American South to the Prairies, suggesting that it would lead to “revolting lawlessness.” The artist’s interest in the petition—beyond its unambiguous proof that blatant racism existed here, too, thus challenging the oft-repeated narrative of Canadian benevolence—lies in its connection with her own ancestry. Her great-grandparents, who came to Alberta from Alabama and Kentucky in 1910, would have been among the households the signatories sought to exclude. In her practice, as well as her teaching at Concordia University, Bowen stresses the familial as a particularly fertile ground for interrogating history. “Every family has stories to tell, and those are inevitably connected to events that explain how Canada has evolved,” she says. “We have been told that Canada’s history is shallow, but we all have experiences that prove otherwise. If we all went and did the work of excavating those stories, we would understand that what we have been told is not the truth.”

Cue the “1911 Anti Creek-Negro Petition” again as substantiation. During its installation at the KWAG, the gallery registrar, Jennifer Bullock, recognized one of the 4,300 signatories: that of Barker Fairley, then a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. A scholar of German literature, he later joined the University of Toronto, where he left a lasting imprint, notably for its relentless championing of the work of the Group of Seven as archetypes of Canadian art. For his contribution, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada, the second-highest civilian honour of merit in the country, and his paintings, though rather unexceptional, continue to be held in collections such as that of the KWAG and Hart House. “What does it mean if Fairley, who established the significance of the Group of Seven and who profoundly shaped our understanding of the visual landscape of Canada, is also a signatory of this petition?” asks Bowen. Among other answers, it is a reminder that art history is made by individuals who insert their beliefs into their choices, which in turn normalizes a certain view of the world. In this case, Canada as terra nullius, as vacant land, as romantic grounds for a budding nation of white settlers.

Bowen’s engagement with archives is exemplary of what Ariella Azoulay sees as the potential of what she termed a responsible “civic gaze,” which considers images as a “source of heterogeneous knowledge that may enable us to reconstruct the lineaments of the regime as it exists in practice…rather than in accordance with the manner in which the regime represents itself.” In this respect, Bowen’s work is at once a critique of the power of archives as institutions that establish and reify a paradigmatic version of history, and a demonstration of how they can be subverted. What she collects and curates aims to show, in her words, “how super-siloed and regimented white-supremacist structures impact people’s ability to put two and two together.” Given the dark truths they can reveal, archives should be regarded as designed to obstruct knowledge. Bowen points out how historical materials are scattered across multiple sites, preventing people from gaining a comprehensive understanding of the networks built to sustain white privilege. Or how, when access is not outright restricted, it is performed with such pomp and circumstance that it imbues the documents with outweighed value, preventing us from seeing them for what they really are. Or, furthermore, how there has been a lack of uptake and support for the type of unraveling research she does.

Bowen is adamant that a disruptive exhibition such as Black Drones in the Hive could never have seen the light of day in the country’s major art hub, Toronto, without having first been shown elsewhere, given how entrenched art traditions and lineages are in the provincial capital. “I left Toronto exhausted from trying to insert myself into the center of Canadian Anglo art,” she confesses. “In my absence, being in Montreal, I can see how impossible my ambitions were. Toronto still is the heart of Victorian-era ambition and ideas of what Canadian art is. There’s no space for an interloper like me to come in and openly question all of it.” Working with the KWAG in Kitchener-Waterloo has also allowed her to collaborate with curator Crystal Mowry, whom she sees as a co-conspirator who deserves equal credit. “The type of curation that Crystal does, which is very much engaged and is neither market-oriented or institutionally driven, is rare and so precious. It’s been an incredible to experience working with somebody who can hold the information in the same way I can and could move around in the archive to find other things to bring to the table, and conceptualize and articulate all of it through her own language. She’s the gift that came at the right moment to manifest this work,” boasts Bowen.

The challenge, for Bowen and Mowry, is not so much in making people come to see what our history is made of, but rather to bring it into the present. “Contemporary society has done this really great job of telling us that this—racism, class violence, colonialism—is a thing of the past and that it doesn’t carry forward,” she explains. “When you do bring forward evidence of the darkness of our country’s foundation, people say ‘that was just the time,’ but they don’t continue the sentence: that racism was an inextricable part of everyday life during that time and that those values got threaded into laws, policies, regulations, rights, and so on, that live on to this day.”

Bowen also recognizes that there is a tremendous responsibility that comes with bringing all of this to the fore; not only in ensuring that the extent of systemic racism is understood, but also that the momentum for unraveling it continues. “You can look away long enough to make something eventually forgotten, and this is what has tended to happen here in Canada,” she observes. However, that responsibility is not hers alone. It is ours, too. Time and again, through her work, Bowen has provided us with the rationale, the urgency, and the blueprints for answering her call to, as she puts it, “snap out of the doldrum,” we’ve been placed in. It’s now up to us to come through.