Around a decade ago, Egyptian journalist and filmmaker Ali El Arabi entered Jordan’s massive Za’atari refugee camp in search of a story. He already had numerous reports from the region for local and international media outlets under his belt. This time, however, he was seeking a story that would help humanize the tale and go beyond the mere numbers and statistics that defines those suffering from the Syrian conflict. He wanted to shed light on the humanity that one can find even within situations that outwardly may appear hopeless.

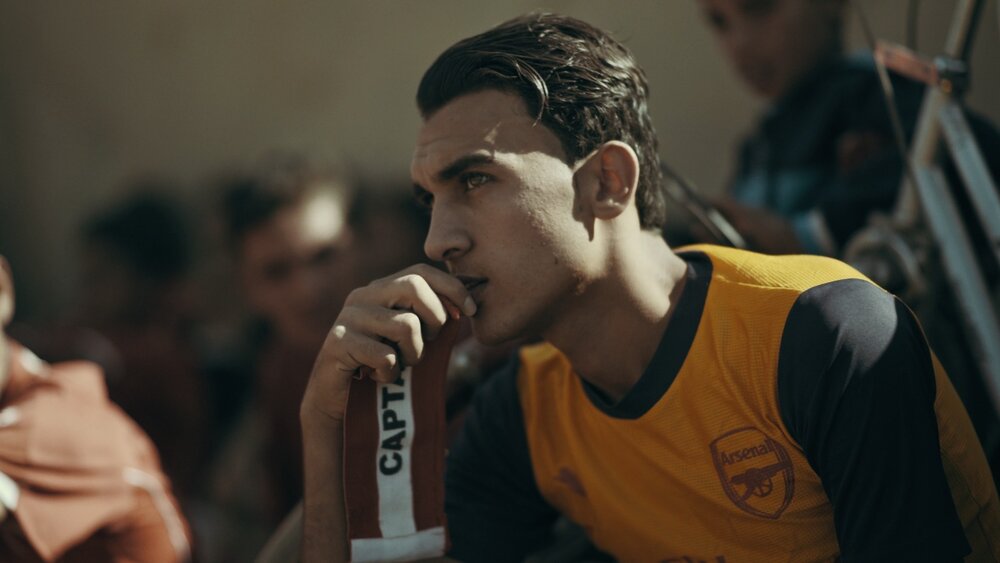

The result is Captains of Za’atari, the emotionally resonant award-winning tale of two friends who dream of success as football (aka, “soccer’) stars. The film follows Mahmoud and Fawzi as they navigate their lives within the camp and find refuge on the pitch. When an opportunity comes to play in front of a foreign crowd at a tournament their futures seem split, showing that the path to success isn’t always a well paved one. Beautifully shot and told with equal parts subtlety and sensitivity, it’s one of the great non-fiction films of the year.

POV spoke exclusively to El Arabi during the Ajyal Film Festival of Qatar, the same nation where the two young men first experienced the life of luxury and excess outside of their regular environment. Home to 2022’s FIFA World Cup, there was a certain surrealism to be in this land of trillion dollar investments and complete infrastructural transformation while talking about this story of two young, struggling men, but this seemed the perfect backdrop to speak of the inherent contradictions of both the region and the film.

POV: Jason Gorber

AEA: Ali El Arabi

The following has been edited for concision and clarity.

POV: What do you see as the difference between documentary and journalism?

AEA: For many years, I was a journalist. I worked for a number of channels, such as the BBC and National Geographic. We filmed everything, but we presented the audience with numbers and statistics without getting close to any one refugee. We couldn’t tell the story from all the angles I wished. Making a documentary is fundamentally different. When I saw my work on the news, I felt it shared only 10% of what I wanted to say. We have problems in the Arab world, including the inability to truly say what we want to say. We even staged a revolution in order to rectify that!

POV: Yes, in this little square called Tahrir.

AEA: Yes, and many of my friends were behind the protests. With my film now in the cinemas around the world, I’ve been given the opportunity to speak to anyone without control from the networks. This is a very different experience for me. With the networks, I couldn’t tell the story using the same tools – my camera, my music, etc. There was a lot I couldn’t say, and was blocked from explaining my feelings to the audience.

POV: That being said, film inevitably has a perspective. This is your version of this story, and people may claim that this story is too happy for the subject. There could be a version of your movie that is far more miserable – Fawzi doesn’t get to join his friend, for example. You could have an angry movie, but instead you have a film which is warm and beautiful and human. Was this always the case? Did you have a version of this film after six years and think this is going to be a sad movie?

AEA: I didn’t write the movie.

POV: Of course, the movie wrote itself as it unfolded.

AEA: Yes, exactly. I followed Mahmoud and Fawzi for years. Talking as a director, if Fawzi stayed in the camp and was separated [from Mahmoud], it probably would have made for an even stronger film. Yet as a human being, I’m very happy he made the team. Maybe the boys would be like this, maybe they would separate. Maybe one would die? Maybe, maybe, maybe.

POV: Do you think the film changed how the two of them were treated by those selecting for the team?

AEA: We had no interference whatsoever in Fawzi’s selection. A number of teams were coming from other countries. Several teams apparently had some issues where there was a one to two year age difference, and the team that was selected was missing a number of players. That is why Fawzi ended up being selected.

POV: Was there a danger in focusing on this success story in that somehow could make the larger story less grievous?

AEA: I, of course, wish I had the same impact on the other people in the film, or the other refugees, as this film has had on Fawzi and Mahmoud. My film is shaped by the stories of all refugees—of Somalis, of Yemenis, etc. —all over the world. My film seeks to convey the idea that these people don’t only need our pity, they don’t simply require basic needs, but they need other, less tangible things as well. Over the past few years, I’ve worked on a number of films in Djibouti, Sudan, and Darfur, and these films generated intense benefits to the refugees of these countries. The reports generated millions of dollars in support. However, I didn’t want to talk about these things, because at the end of the day, I shouldn’t be the only one doing the talking.

POV: What prompted you to look for an entirely different angle on the story?

AEA: The world needs stories like Mahmoud and Fawzi’s. We don’t need more angry and sad stories. I want to give the new generation the hope to continue, to dream, so that one day they’ll find what they want. Maybe you live in a small village India, maybe a small village in Egypt, maybe in a camp in Jordan, maybe anywhere. If you persevere, the opportunity will come.

I feel that often we have something controlling or limiting our dreams. I come from a small village, I don’t have a good education, and I’m not from a rich family. Yet I always had big dreams, and I followed them to get what I wanted. Now I’m a director, everyone knows my name. I produce films and have my own company. This all came from my dreams, so this film explains my own journey, not just Mahmoud and Fawzi’s.

POV: It’s easy to compare your film to Steve James’ Hoop Dreams. Have you even seen it?

AEA: No, I’ve never seen it.

POV: First of all, you should watch it, it’s a masterpiece. If you read reviews of your film, everybody will compare your film to it.

AEA: Yeah, I heard that a lot, especially after Sundance.

POV: Hoop Dreams tells us that dreams and reality sometimes create conflict, that the dream rarely if ever comes true, and can break people trying to achieve it.

AEA: My film ends with the two back in the camp. They still live there. Their dreams of being professional players are halted. If you look back at the first scene in this film, it’s shot with slow motion at magic hour, and Fawzi opens and closes his eyes. This shows that much of this is all a dream. Their entire journey is a circle, one that returns to the starting point, but where their lives were changed by the very act of dreaming. It’s true—the film has started to give them more opportunities. Now we have scholarships coming for them, and we have contracts for them to be coaches. There might be good news coming in a few days, big news, where they would be ambassadors for something important. The impact of the film will be big. This continues to be my goal.

POV: But, and I say this with respect, this happens at Sundance where specific subjects of films are suddenly gifted with charity. People in Park City or Doha, who have lots of money, focus on the subjects of a given film and feed money and opportunities to them. When there’s a sea of suffering, just who the camera points to is almost like a lottery, where picking a charismatic subject is picking a winner. How did you pick these two from thousands? Were you ever worried that you would be changing their lives but making their lives in some ways more complicated?

AEA: First, Mahmoud and Fawzi dream not just for themselves, but also for their families, for all refugees. Whenever Mahmoud and Fawzi speak, they talk of the entire community. Thanks to the film putting them in the spotlight, they are in a strong position to try and speak for the plight of all refugees.

POV: Yet you have this immense responsibility when you picked these two to avoid completely breaking them by following their story.

AEA: I’ve known Mahmoud and Fawzi for eleven years now. I’ve worked with them and my life coach to make them ready for the future. I will give you an example. Yesterday, I went to the big mall, and I gave them my car. I told them go, buy and do what you want and you have this time and these rules. My sister said to me, “Are you crazy? Why did you leave them in the mall?” I answered that I wanted them to have all kinds of experiences from now on. They have good opportunities to be film actors, but that’s a dangerous situation. They’ve been wanting to be soccer players and they should do what they love, and only after explore these other options after getting to know world and how it works. They’re my brothers now. And it’s not just me—I have a big team, my company, and we all work for Mahmoud and Fawzi. We love them a lot.

POV: But, again, you understand that as a journalist, you would never do this. As a filmmaker, it’s complicated, and as a human, of course you do this. As a brother, you do this. But there’s always a danger in telling stories where you get too close to your subject and you can’t see the subject. Was it hard to maintain distance from their story?

AEA: When I finished shooting, I didn’t touch the film for an entire year. I spent that entire time with my life coach to separate myself from the story. I needed distance from the two boys. I already felt I was telling a story about my brothers. There is a scene in the beginning of the film when we see Fawzi slap his sister. At first, I was going to cut it out.

POV: Because it makes Fawzi look bad?

AEA: Yes. After a year of working with my life coach to separate myself from the subject, I was ok to put it in the film.

POV: Tell me about this life coach.

AEA: His name is Namir, and he’s a filmmaker too. He’s French-Egyptian. He knows how to deal with this complexity. I trust him a lot. I told him that I was scared that I was too inside the circle of the story, and not outside enough. I have a lot of love for these boys, and I feel guilty for all of the refugees around the world. He worked with me for a year and then said, “OK, I think you’re ready now, you can start editing.”

POV: How has the response been within the camp to this story? And how has the response been here in Doha, where some of their dreams came true?

AEA: We screened the film for a small group in the camp, and they were happy after watching it because it was the first time they had seen people from their group as heroes. It was the first time they had seen themselves as normal people, not merely as refugees. As for the people here in Qatar, in the beginning, I had a connection here because I had filmed here as a producer. I started to build a lot of friends here to help me to film. At first, I was scared because Egypt has problems with Qatar I thought there was no way the people here would trust me, and then in Egypt, they wouldn’t trust me because I worked in Qatar. But I showed the people here twenty minutes of my film. The people in Qatar saw the film for the first time at this festival. No one tried to control me during any time of the production. I finished shooting here and I went back to the camp thinking if I don’t get money from the Qatar fund, I will finish the film here. We ended up getting zero dollars from the Doha Film Institute.

POV: So who’s the money from?

AEA: My company! I made forty-five documentaries in six years for channels around the world. I put this money into the film.

POV: You know the number one rule of filmmaking is never use your own money!

AEA: [laughs] Yes, but I’m a young filmmaker. If I don’t support my film, no one will support it. Now the film is in cinemas and [distribution] platforms are buying the film.

POV: So you got your money back?

AEA: Not all the money, but I am back here in Doha shooting again. Some people don’t understand what I do – I act like a journalist with my team, and I use small cameras and lived with the boys. We got support from twenty-three funds for this film after the first two years. After we finished it, we started to send material everywhere – to Cannes, Tribeca, etc., and these people put in a lot of money and allowed me to finish my film.

POV: But not from Qatar, not from Jordan, and definitely not from Syria.

AEA: No. I had opportunity to take money from Qatar, but I don’t want to take money and lose any control because people would give me money and want to be co-producer.

Some people [here in Qatar] are complaining that my film doesn’t show the real needs of the refugees. They want to focus on the water situation, the food, and the cold of the camp. I made a film, not a report, and I want the audience to see and to feel. Fawzi’s dad dies of cancer in the film because the camp doesn’t have any good hospitals. How can I tell you the camp doesn’t have hospitals any more than showing that he died? The camp doesn’t have education. The first scene is Fawzi teaching his sister simple English—we can see this easily. We don’t have water, but I don’t want to go the easy way to make everyone see that we don’t have food, please help us. That is not the picture I want to make. It’s the opposite [reaction] in Germany. I screened the film at the Berlin Human Rights Festival, and an old lady came to me. She was crying and she said, “You know, I hated the refugees all of my life. Now, I want to help them all.” This is my message.

POV: This is a crude term, but I hope you understand in English, there’s a phrase that critics will use called “poverty porn.” It’s the fetish where one can sit in comfort and get a thrill out of someone else’s suffering. Your film doesn’t wallow, but it also doesn’t pretend to fix everything.

AEA: It is about the human spirit. Hopefully, it may inspire people who make the decisions around the world to think a different way. We have an entire generation in the camps who do not know anything about life outside the camp. If someone comes, gives these people guns and says, “You are part of the world now,” it will be a dangerous situation. In contrast, when we show Captains of Za’atari and the story of the camp, these same boys and girls look to Mahmoud and Fawzi as role models. We are giving them options to dream and to see role models from within their ranks.

POV: You have lived with a very broken Syria, a complicated Jordan an even more complicated Egypt and a very complicated Doha. Do Mahmoud and Fawzi give you hope for the region’s future?

AEA: In the Arab world, if you don’t have hope, you’ll die. I hope the situation for the refugees ends. I hope the rich countries support the poor countries. I hope for no control from any one for our gas, gold, everything; I hope for a good education for the new generation, to be part of the world. I hope for no more wars because we paid a lot from political decisions; we are not apart from this suffering.

Sometimes my dreams weigh heavily on my muscles and my body can’t handle it. My dreams sometimes are trying to kill me. I came to Doha yesterday, and I shook all night. I thought, “OK, Captains of Za’atari is trying to kill me.” Yet still I dream.

Captains of Za’atari screened at the Aiyal Film Festival in Doha. It plays in Canada as part of the Impact Series on November 26.