Anyone who has worked in the journalism business over the past couple of decades knows we’re in a sad way. Advertising revenues have crashed, staffs have shrunk and the credibility of the mainstream media, according to Pew Research, is at record lows.

To add insult to injury, the world has to deal with the toxic shock jock President Donald Trump, who, when not killing people with magical thinking and bad medical advice about COVID-19, reflexively calls the press “fake news,” a phrase that has caught on. While Fox News and Breitbart applaud, the liberal press is pushed into a defensive crouch, or, as former New York Times editor Jill Abramson put it, episodes of “anguished self-examination.”

Is documentary film ready for a similar moment of reckoning? Has anyone noticed, that the most untruthful American president in history came to office surrounded with documentary filmmakers? Go through the list: Steve Bannon, the former head of Trump’s presidential campaign, chief White House strategist and ideologue, has ten documentaries on his IMDb filmography. Former deputy campaign manager David Bossie, whose Republican group Citizens United opened up the gates to corporate spending on campaign advertising, has 24 credits. Dinesh D’Souza, who wrote and directed four successful political films, was rewarded by Trump with a pardon for his campaign fraud conviction. Alex Jones, radio host and auteur with 14 directing credits has so much in common with the president’s thinking that he sometimes seems to be playing Cyrano to the president’s Christian.

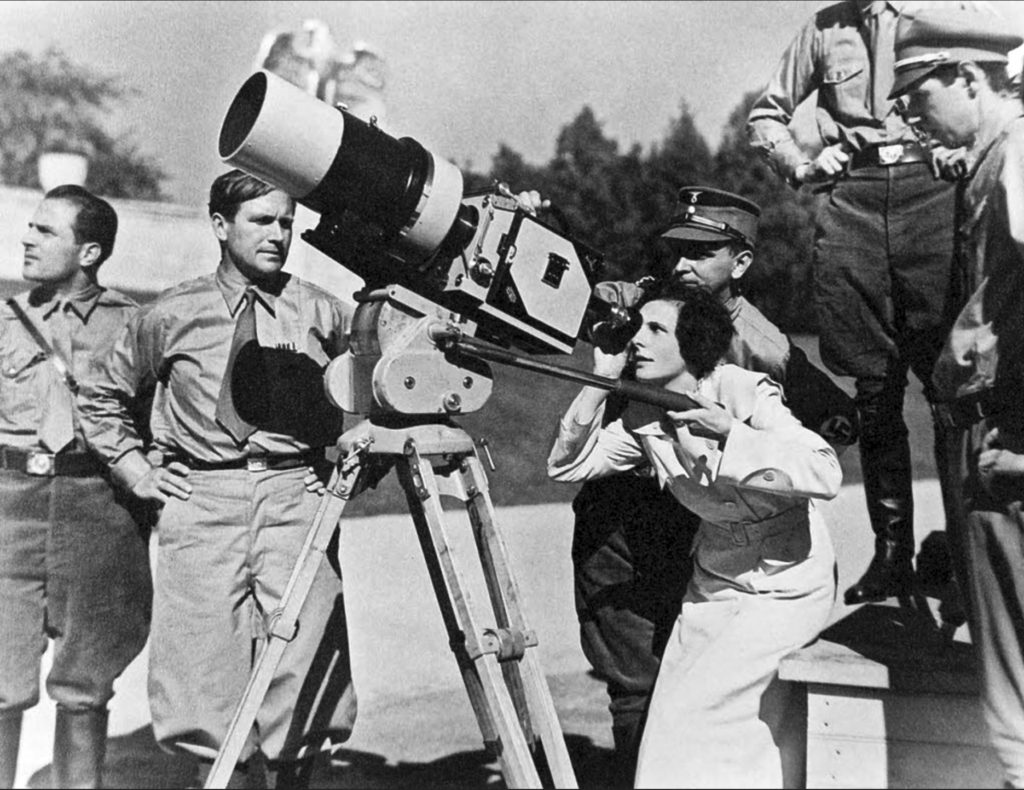

How do we square the noble tradition of documentary film with a president who utters falsehoods, according to the Washington Post’s running tab, more than 100 times a week? The problem is that creativity often beats out actuality: The documentary tradition is also rooted in the opposite of truth, propaganda—the thundering docudramas of Sergei Eisenstein, the Nazi super-spectacles of Leni Riefenstahl, the mobilization drive of Frank Capra’s Why We Fight. You could even say the potential for falsehood defines the genre: As Dirk Eitzen’s wrote in his 1995 essay, “When Is A Documentary?”: “A documentary is any motion picture that is susceptible to the question: ‘Might it be lying?’”

By contrast, news, by definition—verifiable information in the public interest—cannot be “fake” and Trump’s snide phrase is an oxymoron, with a specific contemporary history. Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed’s Toronto-based media editor, explained in a 2017 column that the original term, which he first used in 2014, referred to disinformation on social media, created either to earn advertising revenue or, as in the case of the Russian troll farm Internet Research Alliance, to spread political influence.

That meaning of the phrase flipped from descriptor to epithet on January 11, 2017, during Trump’s first press conference as president-elect, when he told CNN’s Jim Acosta: “I’m not going to give you a question—you are fake news.” The epithet, as Russian-American journalist Masha Gessen has pointed out, is really just a “power lie,” like the bully who stole your hat in the schoolyard and says, “Prove it’s not mine.”

Both UNESCO, which has published a journalism handbook on fake news, and a United Kingdom Parliamentary committee on the subject, warn against using the toxic term, especially since it has been adopted by right-wing politicians from Brazil to the Philippines. By now, the problem is the unextractable pee in our public swimming pool.

Disinformation has become a worldwide multi-threat moral panic, a phrase Marshal McLuhan coined in Understanding Media (1964) to describe the social shock of the new electronic environment. There’s the terror of mind-control (Netflix’s documentary The Social Dilemma), of collective psychiatric damage (Bryan Welch’s State of Confusion: Political Manipulation and the Assault on the American Mind), and especially of totalitarianism (Masha Gessen’s Surviving Autocracy), historian Timothy Snyder (On Tyranny), and Ece Temelkuran (How to Lose a Country). At an extreme, there’s a collapse of any agreed-upon standard of truth: in her book The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump (2018), New York Times book reviewer Michiko Kakutani blames leftist postmodern philosophers for destroying our faith in objective reality and emboldening anti-science fanatics.

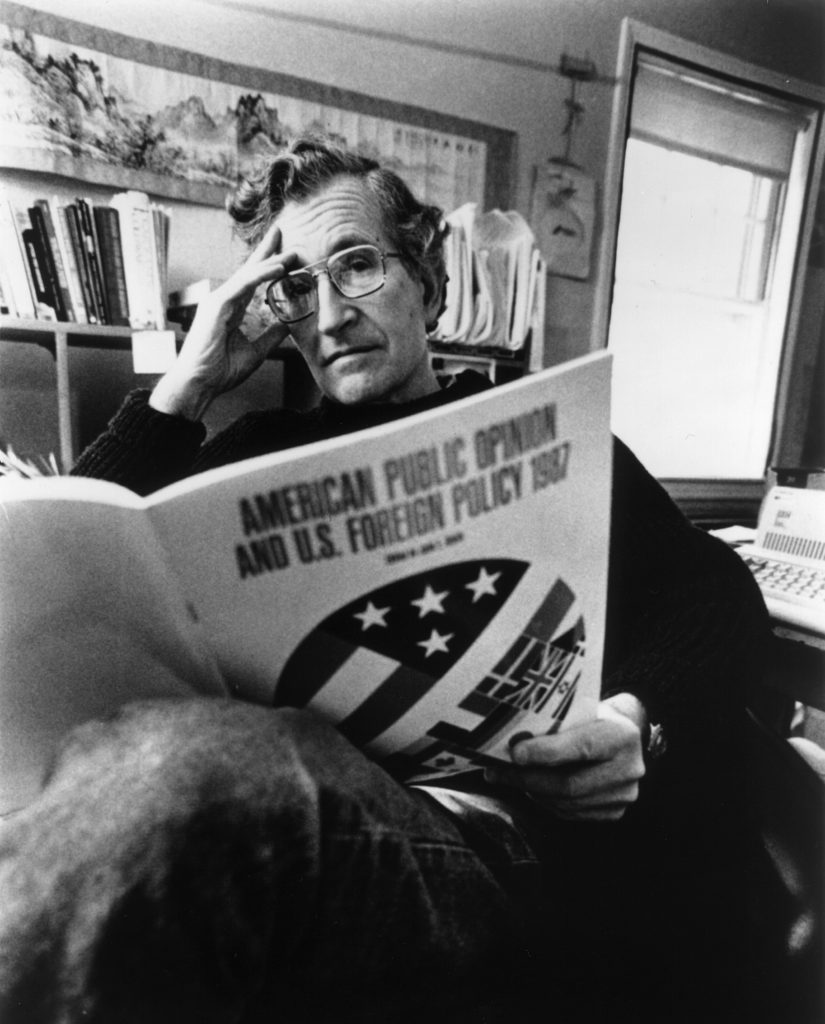

What’s worth remembering is that such disinformation is almost always about political power. (Fake business or sports news is relatively rare.) How has documentary film, an old partner of political messaging, helped explain the contemporary information malaise? One place to start a discussion about media and propaganda is Peter Wintonick and Mark Achbar’s Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (1992). The film, and Chomsky and Edward S. Herman’s 1988 book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Media on which it was based, address issues of the government, press, and disinformation.

The film was released at the end of the Cold War, at the beginning of the rise of 24-hour cable news channels, the dawn of the bitter political divisions that historian James Davison Hunter describes in his book Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (1991). Manufacturing Consent struck a resonant chord with an international audience, playing in 300 cities around the world, subtitled in a dozen languages. A warmer, more humorous film than its sober subject suggests, Manufacturing Consent follows the rumpled, gravel-voiced professor, a renowned linguist turned political activist, on various speaking engagements as he outlines his “propaganda model” of corporate media. The argument is that corporate media justify the actions of intelligence agencies and the state, limiting public debate, and rationalizing or ignoring U.S. state terrorism. The argument rang true for many at the end of the first Gulf War; it was glaringly so by the second Gulf War in 2003, when the New York Times credulously reported on Iraq’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction based on false U.S. intelligence leaks.

This distrust of the consensus-oriented mainstream liberal media, from left and right, continues to lead to the bewildering horseshoe or mirror effect. The phenomenon is notable in the case of filmmaker Michael Moore. Despite his ideological differences to Trump, Moore fits a similar stereotype: another comically overweight truth-telling clown in a trucker cap with a gift for insulting his rivals, who claims to speak for the forgotten manufacturing workers against globalist elites.

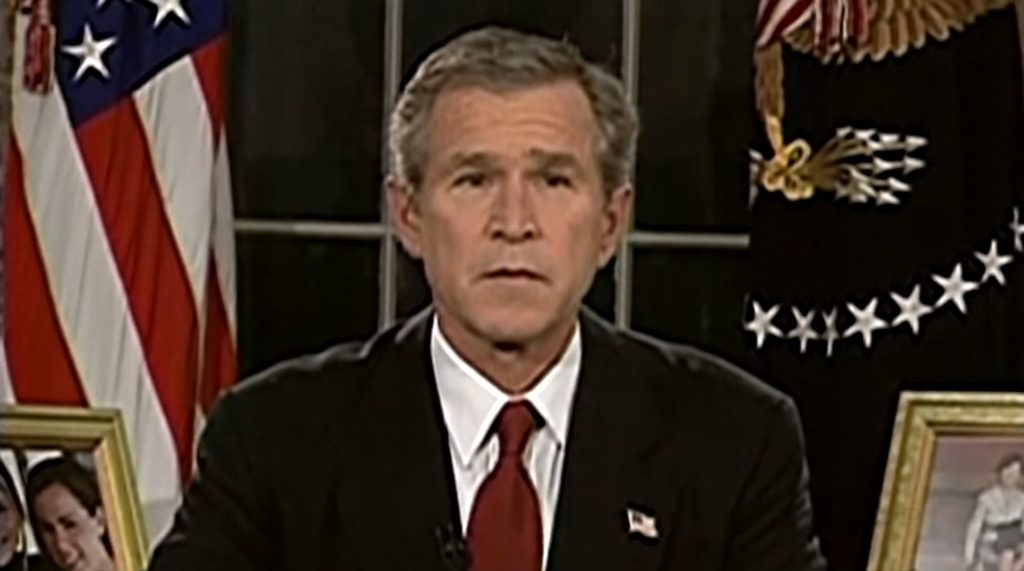

Michael Moore’s blockbuster Fahrenheit 9/11, a scathing account of the presidency of George W. Bush and the Iraq War, became the most successful theatrical documentary of all time with a global box office of more than $220 million. At a 2004 press conference for the film, the filmmaker declared, echoing Chomsky: “My movie exists to counter the managed, manufactured news which is essentially the propaganda arm of the Bush administration.” But is the film simply a spectacle of counterpropaganda? Psychologist Kelton Rhoads, a specialist in influence and persuasion techniques, wrote a 14,000-word paper analyzing Fahrenheit 9/11’s use of propaganda techniques. Reviewers enthusiastically concurred: David Edelstein in Slate described the film as “an act of counter-propaganda that has a boorish, bullying force. It is, all in all, a legitimate abuse of power.” Power, in this case, was about mobilizing and persuading voters, shifting the axis of documentary film from investigation to provocation.

But Moore’s success and confrontational style opened a Pandora’s box of speculative and manipulative conservative response films, and “defactualization,” to use Hannah Arendt’s term, of public discourse. These aren’t the kind of films you’ll likely see at your local theatre or on public television, but they do have their true believers.

As Fahrenheit 9/11 started breaking records at the box office, David Bossie, the head of the political action committee Citizens United, decided it should be stopped. (Back in 1988, the same organization was responsible for the notoriously racist Willie Horton attack ads on Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis.) Bossie saw a threat, and petitioned the Federal Election Commission to have Moore’s film’s marketing treated as political advertising, When the case was dismissed, he slapped together a response film, Celsius 41.11: The Temperature at Which the Brain Begins to Die, which elaborated an apocalyptic agenda via juxtaposed images of the World Trade Centre attacks, the bombing of the USS Cole, Michael Moore, Hitler, and John Kerry.

As Bossie told the Los Angeles Times, “Documentaries have become a weapon of the Left. After seeing Moore’s impact, I wanted to counterpunch.” In 2008, Bossie released Hillary: The Movie, which was intended to go on cable directly before the 2008 Democratic primary. When the FCC banned that film as election advertising, Citizens United challenged the ruling and won a Supreme Court decision removing spending limits on corporations funding election ads.

2004 also saw the first documentary from Moore admirer Steve Bannon, who was already a Hollywood producer (Titus, The Indian Runner). His first directorial effort, In the Face of Evil: Reagan’s War in Word and Deed (2004), extolled Reagan as the hero who brought down godless communism. In 2011, Bannon told the Wall Street Journal: “I’m a student of Michael Moore’s films, of Eisenstein, Riefenstahl. Leave the politics aside, you have to learn from those past masters on how they were trying to communicate their ideas.”

What are Bannon’s films like? Politico reporter Alex Wren bingewatched his entire oeuvre so the rest of us don’t have to: “They flicker with stock footage of a pride of lions noshing on a bloody zebra’s flesh, blooming flowers, rearing grizzly bears; there are towering mushroom clouds and seething Hitler speeches that flash on the screen while we hear a monologue from talking heads like Newt Gingrich and Phil Robertson of Duck Dynasty fame.”

Bannon, for all his heavy-metal thunder, is almost normal compared to Dallas-based Alex Jones, who, through his radio show and website InfoWars, is a key figure in the world of conspiracy theories and fake news. (Noam Chomsky, consistent with his dedication to free speech absolutism, has been a guest on his show.) Jones’ filmmaking predates Fahrenheit 9/11, with his first effort, America: Destroyed by Design (1998) being the first of a series outlining an impending totalitarian world order, the climate change hoax, eugenics, weather manipulation, and (alleged) Satanists from Lady Gaga to Glenn Beck.

After Barack Obama’s 2008 election, Jones went mainstream. His film The Obama Deception: The Mask Comes Off was widely advertised in conservative media and garnered more than four million views on YouTube. And Donald Trump, after announcing his candidacy, appeared on Jones’s show and called the host “amazing.” The PBS Frontline documentary United States of Conspiracy shows some of Jones’s bizarre fictions, which range from the Chinese climate “hoax” to stories of undocumented immigrants casting millions of votes, repeated by Trump.

By far the most commercially successful of the conservative documentarians is Dinesh D’Souza, a journalist who worked as a policy adviser in the Reagan White House and went on to write a series of best-selling conservative books. His greatest doc success was 2016: Obama’s America, which asserts the president, steeped in anti-colonialist ideology, wanted to reduce the United States’ power. The film earned more than $33-million, making it the second-highest grossing political documentary domestically in history.

Like Bannon, D’Souza has also been inspired by Michael Moore’s success: “I remembered that Michael Moore had made Fahrenheit 9/11 and unloaded it before the 2004 election, and I thought the conditions weren’t so different right now—we have a controversial president and a country that is divided—so I wanted to do a similar thing.” By 2016, when D’Souza made his next film, Hillary’s America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party, film publications like IndieWire and Variety began calling him the “the Michael Moore of the right.”

None of this is to imply that the director of Fahrenheit 9/11 and Bowling for Columbine is responsible for the rise of Trumpism. But Moore’s success and sheer demagogic appeal have inspired a lot of bad actors.

Yet even in an age when anyone with a YouTube account and a laptop can offer bad COVID advice or talk trash about politics and the media, there are important, rigorously researched documentaries about real conspiracies: Alex Gibney’s Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), exploring the giant energy company’s systemic corruption; Charles Ferguson’s exploration of the 2007–08 financial crisis, Inside Job (2010); Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon’s The Central Park Five (2012), chronicling the tragedy of a racist justice system; and Laura Poitras’s Citizenfour (2014) about Edward Snowden and the National Security Agency surveillance scandal. In this deeply abnormal moment, should all soldiers in the information militia stand at attention and declare a vow of purity? A ban on rhetorical voice-over questions? No more menacing slow-motion walks, ominous music, infantilizing animation, fluttering flags, shuttered factories, images of Hitler or 9/11? Should every documentary open with a cigarette-style label, warning that all narratives are socially constructed and potentially dangerous?

The answer is, obviously, no. In the midst of this ideological firefight, it’s important to keep the bullshit detector dialed to ten, but also to keep open to all kinds of intel. Only totalitarians insist on one acceptable version of a story, or one way to move people to action. We should take as a warning British filmmaker Adam Curtis’s trippy archival montage, HyperNormalisation (2016), which explains how bankers, politicians, and tech nerds, beginning in the 1970s, have replaced reality with a simpler fake world.

News, stripped of its marketing and commentary, can be seen as little more than concrete dust, ready to be built into grander informational structures. But the spadework—news gathering, working sources, fact-checking, confirming evidence—has been key to chronicling the disaster of the Trump presidency. Noam Chomsky said in an interview last year that the first thing he does every morning is read the New York Times. “You have to critically analyze what you read and understand the framework, what is left out and so forth, but that is not quantum physics; it is not hard to do.”

As one of those controversial so-called “post-truth” philosophers, Bruno Latour, observed in his recent book Down To Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, facts are as strong as their context: “Facts remain robust only when they are supported by a common culture, by institutions that can be trusted, by a more or less decent public life, by more or less reliable media.”

Which sounds, more or less, heavenly.