Charlie Chaplin is one of the most iconic film actors. Audiences have loved his character the Little Tramp for generations. Films like City Lights, The Gold Rush, and The Great Dictator play as well today as they did during silver screen era.

While many people recognize Chaplin, however, few people actually knew him. The Real Charlie Chaplin, directed by Peter Middleton and James Spinney (Notes on Blindness), explores the two Chaplins: the one immortalised on screen and the public figure who led a private life. The film is a movie buff’s treat as it offers a wall-to-wall collage of Chaplin’s best work. Snippets from the silent era highlight his knack for physical comedy and his early efforts at social commentary. Fascinating footage from City Lights inspires one to look at a classic film anew as the doc recounts Chaplin’s painstaking efforts that took over a year, and dispensed with one actress, to get right. Middleton and Spinney leave it to audiences to decide if the genius merits the madness.

Cinephiles will love revisiting the classics, but the gem of the film is an audio recording from an interview Chaplin did with Life magazine. The usually guarded star is disarmingly candid here. Chaplin’s words evoke his story, warts and wall, as the silent star finds his voice. The effect is reminiscent of Maximillian Schell’s 1984 documentary Marlene, which offered a portrait of actress Marlene Dietrich using only her voice as the cameras roamed her apartment. Middleton and Spinney revisit Chaplin’s old haunts, too, and add the voices of people who knew him as a young lad through dramatic recreations that draw upon interviews and archives. As film on film bios go, The Real Charlie Chaplin lets audiences rediscover one of the most influential artists of the medium, and perhaps find new lenses through which to (re)explore his works.

POV chatted with Middleton and Spinney by Zoom ahead of the film’s premiere on Crave and Showtime. Unfortunately, a technical glitch on my end disrupted the audio, so the filmmakers graciously sent their answers again via email.

POV: Pat Mullen

CC: Peter Middleton and James Spinney

POV: Why Chaplin and why now?

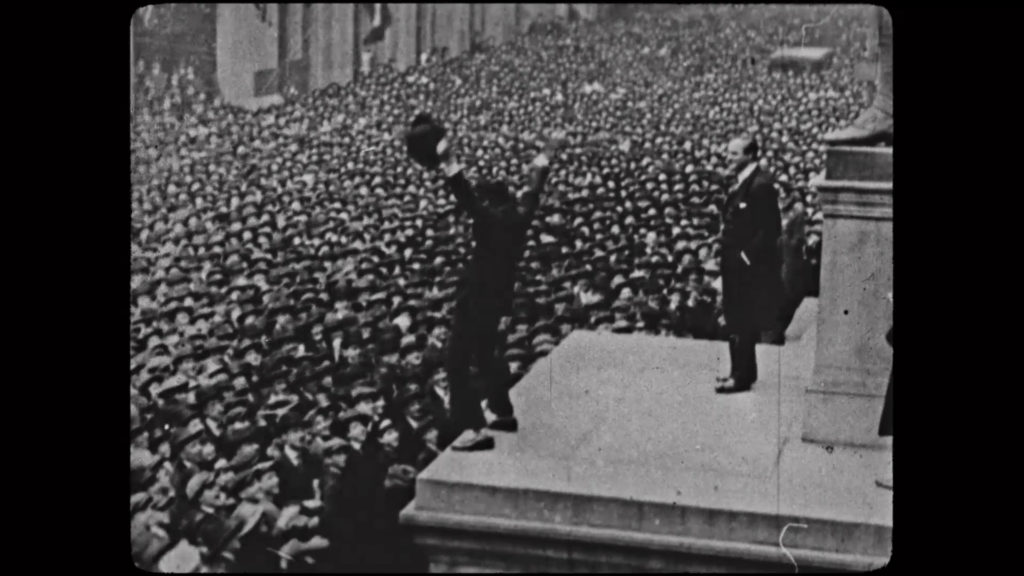

CC: Chaplin was a giant. Even today, over a century after he first stepped onto the screen, his name brings an image into people’s minds: the figure with the hat, cane, and moustache. But this is just a shadow of the fame he experienced during his lifetime. When he made his first short films, movies were beginning to spread across continents. Within a few years, hundreds of millions of people were regularly watching Chaplin films, which defied language and cultural boundaries.

Nowadays, we’re less familiar with his films or his extraordinary life story, which took him from a Dickensian childhood on the streets of South London to Hollywood at the beginning of cinema. We wanted to make a film that could be an entry point into his life and work, which are so intertwined. As the Tramp, he was constantly journeying inwards, replaying his traumas, fears, and humiliations. But despite the emotional vulnerability he displays on screen and the intimacy he created with audiences, the people who knew him best found him to be something of a mystery. He was recognised all over the world but he seemed to be unknowable. This became our starting point.

POV: You previously drew on audio recordings in Notes on Blindness and for this film, you worked with John Battsek who produced Listen to Me Marlon, which had such a unique way of recreating Brando’s presence. What was your process of finding Chaplin’s voice, so to speak?

CC: There have been hundreds of books written about Chaplin in dozens of languages, alongside many brilliant documentaries. We went looking for material that we hoped would shed new light on his life and crucially give us a glimpse of his character. We quickly became interested in the theme of voices, which made us wonder: what did Chaplin, the icon of silent cinema, sound like?

We found clues in a recording from 1982 of the film historian Kevin Brownlow interviewing Chaplin’s childhood friend, Effie Wisdom. She remembers South London in the 1890s, the ragged clothes the young Charlie wore, the hunger that was such a feature of his youth. And in a thick cockney accent, she gleefully tells Kevin, “He used to talk like me. Common!”

By the time he became famous, Chaplin had cultivated a very different voice. It was rarely captured on tape because Chaplin hated interviews. But in 1966, fourteen years after his departure from the United States, he allowed a tape recorder into his home in Switzerland for an interview with Life magazine. Conducted over several days, it’s by far the most extensive interview he ever gave, capturing Chaplin telling his story in his own words.

Our final discovery was a recording that was thought to be lost. The press conference for his film Monsieur Verdoux in 1947 has become a legendary event in Chaplin history. By this point, the tide of public affection was turning against Chaplin. “You’ve stopped being a good comedian,” one journalist tells him, “since you have been bringing messages.” We hear the resentment towards Chaplin’s development from silent clown to political commentator, which would eventually lead to his exile from America.

POV: What was the process of restoring the Life magazine interview?

CC: It had taken Life magazine reporter Richard Meryman over a year to secure an interview with Chaplin. Sensing Chaplin’s self-consciousness, he placed the tape recorder at a distance, so the recording is very faint. This had deterred most filmmakers before us from using it. At first, we were concerned it may not be salvageable, but recent digital techniques allowed careful restoration of the recording and eventually, from behind the thick layers of noise, Chaplin’s voice emerged.

POV: In terms of the re-enactments, how did you go about casting Chaplin and your approach to presenting him? I notice that we often see Chaplin from behind, or his image might be obscured. Actors like Robert Downey, Jr. have played him successfully, and the film notes that he’s inspired countless imitators, so I was wondering what inspired that approach?

CC: As we listened, we found ourselves transported into Chaplin’s mansion in Vevey, Switzerland. The house is now a museum, which looks very much as it did in 1966. We began to imagine restaging the interview in the room it took place with actors lip-syncing to the original recording.

Jeff Rawle, who played Chaplin, studied footage of him to guide his gestures and movements. We shot Jeff’s performance in fragmentary glimpses so that we could intercut the scenes with photographs that were taken during the interview. The staging and actors’ movements were largely determined by the photographs and the audio recording. We took similar approaches with the Effie Wisdom interview and the 1947 press conference. These three dramatic strands became present tense spaces within the film, from which we tumble into archive material and film clips.

POV: What sort of access did you have to the Chaplin family archive? Were there challenges in terms of accessing materials given that Chaplin has such a complicated family?

CC: The Chaplin estate were generous and trusting throughout the making of the film, never trying to exert any editorial pressure or control the narrative. They gave us unlimited access to their archives, which included thousands of photographs, newspaper clippings and behind the scenes material.

Some of the most intriguing material in the archives is the home movies shot by Chaplin’s fourth wife, Oona. Here we see Chaplin playing with his children at home in Switzerland. In the film, these images are accompanied by new interviews with Geraldine, Michael, Eugene, and Jane Chaplin reflecting on their attempts to understand their father. Jane spent her childhood dreaming of having a conversation alone with him. “I had grown up with the icon,” she says in the film, “but I had no idea who the man was.”

POV: The doc looks at that great scene in City Lights where Chaplin took a painstakingly perfectionist approach to his work. Do you have any moments where you can relate to that – working as filmmakers to find some exact result that keeps getting away from you?

CC: Chaplin described his process as placing yourself in a labyrinth and trying to find your way out. We definitely found ourselves lost in a kind of labyrinth making a film about him. And just as Chaplin would develop a few set pieces and then puzzle over integrating them into an overall plot, our starting point was to identify things that felt crucial to understanding Chaplin and working outwards from there.

We spent a long time experimenting with structures and there were so many different iterations of the film along the way. Over time, we decided to embrace a variety of approaches and perspectives, like Chaplin’s Tramp costume, which is a kind of collage of disparate elements.

POV: Silent cinema works at such a different pace than contemporary cinema, so were there challenges in terms of showing Chaplin’s work, while also keeping it lively in the pace and trajectory of his story?

CC: This was a real challenge. Watching Chaplin films, you settle into a different mode of viewing. He plays out shots in wide frames, using cuts sparingly. Placing these scenes in new contexts, there can be a conflict of different rhythms, especially as we found that you can only really appreciate Chaplin sequences when you let them play out. Cutting them down, you quickly realise how expertly constructed they are, how deftly they build, develop, and climax. If you cut too deep, it’s like hearing a tiny snippet of music out of context.

For us, this necessitated selecting fewer films (we don’t cover A Woman of Paris, The Circus, Monsieur Verdoux, amongst others) so that we could let selected set pieces play out for longer. Some of these omissions were painful. But that’s the price of making a film about someone who has such a rich body of work. After all, many great documentaries about Chaplin have focussed on just one year, or even a single film.

POV: Do you think generations of film history might be lost as we shift to digital?

CC: Chaplin’s films were so popular that they were endlessly reproduced, so fortunately we still have all of his films today. But he’s the exception: over 90% of silent cinema has been lost. What has survived is so precious. The Chaplin archives are safely housed in the Cineteca di Bologna and the BFI [British Film Institute], which have Chaplin’s rushes. When you watch century-old 35mm Chaplin outtakes on a Steenbeck in the BFI, you realise how stable a format celluloid was. Digital technology is fast moving. [We] hope film historians in 100 years will be able to delve into the rushes of today’s masterpieces as we have Chaplin’s.

POV: Chaplin’s story is interesting to revisit now in light of the #MeToo movement, where many actors or filmmakers have fallen out of favour because they were held accountable for their actions, either personal or professional. What might you say to audiences who think that Chaplin’s personal life makes it problematic to celebrate his work?

CC: It’s a question we wrestle with in the film. It’s striking to hear Chaplin’s second wife, Lita Grey, remember how she was vilified not only by the media and but prominent intellectuals because of Chaplin’s status as “a genius.” She describes how she was disbelieved because the public couldn’t reconcile the incidents she described with the character they loved watching on screen. In another interview, Lita says, “awe is a kind of fear.”

POV: Is there a Chaplin of today?

Few filmmakers today are able to work in the way Chaplin did. It was unique even at the time. He was producing the most expensive comedies yet made without a script, or even a sense of where the film was going. But his unique process of finding the story as he went, which is so antithetical to the meticulous planning of filmmaking today, brought these stunning works into being. Even if the process took him and everyone around him to the edge of madness.

The Real Charlie Chaplin debuts on Showtime and Crave on Dec. 11 at 8:00 pm.