Jessica Beshir’s lyrical Faya Dayi and Daniel Kötter’s formalist Rift Finfinnee, two oddly similar films set in an Ethiopia struggling with the upheavals of urbanization and industrialization, are almost excellent movies. Both are a little overly enamoured of their very accomplished aesthetics, which at times render distant and abstract what might have been better served by a more direct or varied approach. Still, there is much to recommend them.

In Faya Dayi, khat, a mild stimulant grown and mostly used in east Africa, becomes a metaphor for the impasse in the social and political life of Harar, the picturesque walled city in Ethiopia in which the film is set. Khat, it is briefly explained near the beginning of the film, became the region’s dominant cash crop because it is less water-intensive than the formerly preeminent coffee. Intersecting with this economic story is a level of myth: a whispered story told in fragments at the beginning, middle, and end of the film, relates khat’s purported discovery by a Sufi mystic.

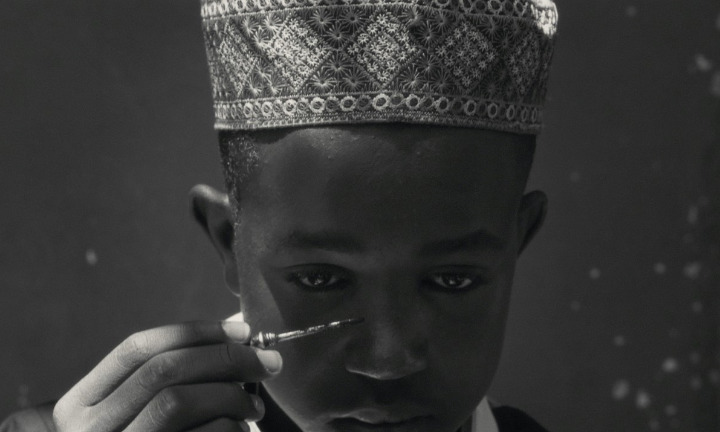

The film’s most obvious strength is its often shockingly beautiful black-and-white cinematography. Beshir’s camera lingers on textures—fabric, steam, walls, mud—in a way that renders them almost tangible. Yet the combination of this material attentiveness with largely disembodied voices—we rarely see the people speaking as they are speaking, even if we hear their voices as soon as something else is on screen—produces a strangely depersonalized hypnotic effect. The film’s rigid adherence to a flowing, lyrical mode comes at the expense of dynamic range, to the point of monotony: every story more or less sounds the same, even if they are very different.

I am not sure this is really well advised. Why not tell the story of khat’s mythic origins in one piece at the beginning of the film? Why don’t we see people talking to each other? Why do episodes flow into each other with no clear distinctions? It’s not that the dissociative poetics aren’t effective; they are, and it’s easy to drift along with it. But the film is largely about young men trying to leave behind lives of poverty, whether by migration to Europe or by chewing khat. The film’s languor somewhat dulls all this.

In Daniel Kötter’s Rift Finfinnee, the very different but equally striking cinematography—reminiscent at times of Ed Burtynsky’s work in peripheral industrial landscapes, at other times of Alexander Gronsky’s photographs of suburban landscapes in post-Soviet Russia—takes as its subject the newly developing suburbs of Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa (Finfinnee in the Oromo language). Beyond its visual splendour it also shares Faya Dayi’s disembodied audiovisual style; rarely do we see people actually talking to each other, and when we do, it is often at such distance that it can be difficult to perceive who is speaking.

It is not immediately obvious from the film’s initial shots of the Great Rift Valley, over which plays a musique concrète-style soundtrack of what seems to be a radio documentary about the region’s deep geology, but Rift Finfinnee is a story about urbanization. In fact, one gradually realizes that what’s happening here is the primordial story of primitive accumulation and the birth of industry. The Ethiopian government has bought up land from Oromo farmers in the area east of Addis Ababa to enable the city’s growth, we hear from the film’s various voices, and we see aspects of this process underway: men break stones, grind them into aggregate, mix it with water to create cinderblocks, and, out of them, fill the previously pristine landscape with dozens and dozens of ten- or twelve-story apartment buildings, and row upon row of identical suburban houses for the more affluent. Key scenes demonstrate the fundamentally pre-industrial or pre-capitalist nature of the process: in the absence of sophisticated machinery, it takes five men working constantly to relay cinderblocks from a pile on the ground into a truck; water is brought on foot up to the top of a building under construction; a voice that seems to be a local captain of industry bemoans the lack of infrastructure that would make urbanization quicker and more efficient.

Many of the film’s lingering shots of arduous labour and partial urban landscapes will stick with me for a long time; they depict a reality too little seen—a reality that Mike Davis, in Planet of Slums, argues is the lot of the majority of the world’s poor, and therefore of the world’s population in general. And the (literal) grounding of the film’s social, political, and economic story in geology—the rocks from the Rift Valley end up cinderblocks in apartment buildings—is cleverly done. As with Faya Dayi, though, I am not entirely convinced that the film’s singular approach always serves the material as well as it could. As a photo essay or exhibit that juxtaposed subjects’ monologues and conversations opposite Kötter’s striking images, Rift Finfinnee might well have been a masterpiece. As a film, its approach is perhaps a little sterile.

Both films are perhaps also a little overly subtle about a background event that all the press materials insist on: civil war. There are mentions of ethnic strife in Rift Finfinnee — one man hopes that urbanization will bring peace — and, I suppose, that it’s also in Faya Dayi, though I struggle to recall specific instances. But it is never spelled out. It isn’t obvious to me why such an important event should be quite so obscured. Many poetic documentaries, The Act of Killing and Bisbee ’17 to name two, integrate historical trauma in a way that feels organic and non-didactic, whether in the action or by way of a brief title card. Such tactics might have served these films well.

Nevertheless, the two films reward the viewer’s patience and attention—after a little bit of supplementary research.