The line between documentary and experimental film can be very blurry indeed. To define documentary, with Grierson, as the creative treatment of actuality—or at least some approximation of it—is to create a term with the capaciousness to include works far removed from what has become the canon of doc film: Stan Brakhage’s ecstatic home movies, Hollis Frampton’s formal experiments, Chris Marker’s poetic essays.

For the prolific British filmmaker John Smith, the distinction between document and experiment—the discovered and the constructed—is a tension that has sustained and structured his work since the mid 1970s. Little known in North America, Smith is revered as something between a cult figure and a national treasure in the UK, and is enjoying a bit of a vogue 50 years into his career: MUBI has been streaming a selection of his films, e-flux and ArtReview have hosted standalone works in their film clubs (Blight [1996] and Citadel [2021], respectively), and, most significantly, Smith was honoured with an exhaustive four-part, 50-film retrospective—dubbed an “Introspective,” a pun that reflects both Smith’s playfulness and his self-reflexiveness—in London late last year, divided between the Institute for Contemporary Arts and Close-Up Film Centre, which sold out so quickly that I didn’t get a chance to attend a single screening. At the North London gallery and library space of LUX, Smith’s distributor, where over the course of a few days I caught up on what I had missed, Smith enjoys a certain pride of place. The staff were amused when I asked (in all naivete) if they were familiar with his work, a question that turns out to be the rough equivalent of walking into the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre in Toronto and asking if they’ve ever heard of Michael Snow.

Smith was born in Walthamstow, East London, in 1952, and has never strayed far. After attending the North-East London Polytechnic and the Royal Academy of Art, he became involved with the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative (developed on the model of Jonas Mekas’ New York-based Filmmakers’ Co-operative), the home of avant-garde structuralist filmmaking in the UK and the predecessor to LUX. As A. L. Rees, the UK experimental film scene’s own P. Adams Sitney, noted, Smith’s sensibility was very different from those of his fellow co-op members, like Malcolm le Grice, Lis Rhodes, and Stephen Dwoskin, who were more in tune with North American structuralists like Snow, Hollis Frampton, and Paul Sharits. The difference in Smith’s work derives from his dry, deadpan sense of humour and his sense of place: The vast majority of his work is made in East London, mainly Hackney and Leytonstone, and no matter how abstract or formal his concerns can be, that world in all its diverse working-class and bohemian cacophony and ferment inevitably intrudes, which Smith tends to welcome. Where structuralist film tends to impose form extrinsically or mechanically, with the real world beyond the camera almost irrelevant, Smith draws inspiration from the world around him—in fact, mainly the view out his window—and allows it to inform and disrupt his formal experiments.

Considering Smith’s work alongside the documentary and structuralist cinema traditions helps to clarify Grierson’s conception of the documentary (which, in interviews, Smith favourably cites): It’s not just the creative treatment of actuality tout court, but the creative treatment of actuality in which “actuality” is given a certain precedence over its “creative treatment”; in other words, the creative treatment needs to be in some sense beholden to the actuality beyond the camera to qualify as documentary. Put it this way: Snow’s Wavelength (1967) is only incidentally “about” a New York City apartment; Smith’s films, no matter how experimental or fanciful, really are ultimately about London council flats, street life, COVID lockdowns, and so on.

Smith’s work is aesthetically varied. It’s always minimalist, though the specific modality varies depending on the film. Often, like Frampton or Peter Greenaway, he constructs films out of static shots and non-sync soundtracks built from snatches of speech and found sound. At other times, as in Hotel Diaries (2001–7), Smith opts for long and unscripted handheld takes with improvised, off-the-cuff narration, seemingly eschewing the entire formal language he had developed elsewhere. His films are often comic, in a definitely British register, courtesy of his love of Monty Python. They are also slyly political, occasionally poignant, and sometimes, as in The Black Tower (1987), even a bit unnerving. If some of his films—above all, the TV doc Hackney Marshes (1978) and the elegiac Blight—seem like sophisticated and systematic reworkings of the codes and conventions of film and audiovisual media, others—like Hotel Diaries or Steve Hates Fish (2015), a film in which Smith forces a smartphone app to read English-language shop signs as if they were in French and then translate them back into English, with charmingly odd results—are so off-the-cuff and lo-fi and bizarre and unfiltered that it seems like he has transcended film language entirely by refusing to take it seriously.

At his best, in films like The Girl Chewing Gum (1976), Hackney Marshes, The Black Tower, Blight, The Hotel Diaries, and Citadel, Smith simultaneously deconstructs and reconstructs documentary language to develop novel aesthetics that reflect ironic engagement with the experience of daily life in his little corner of East London under a succession of quixotic political-economic programs: the crumbling welfare state of the 1970s, Thatcherite austerity, the gentrification of the 1990s, the war on terror, Brexit, the isolation engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic, the disorienting effect of the new gilded age on the average citizen.

In his early classic The Girl Chewing Gum, still his best-known film, Smith playfully subverts the conventional construction of transparency in documentary film through a sort of slapstick structuralism that obliquely approaches similar conceptual terrain to that of Wavelength or Frampton’s (nostalgia) (1971). Inspired by a scene in François Truffaut’s Day for Night (1973) and bearing a family resemblance to Chuck Jones’ animated classic Duck Amuck (1953), Smith’s film pairs documentary footage of people going about their business at a busy corner in Dalston with a narrator ostensibly “directing” them: Walk this way, walk that way, go a bit faster, etc. Gradually, the behaviour of the “actors” grows too fast and complex for the narrator and he starts to fall behind, describing the scene instead of controlling it, to comic effect. He also invents backstories for some of the people he sees and, departing from the fiction entirely, muses about his own (presumably true) misunderstanding of the lettering on the side of the building. By the end of the film, the narrator is “revealed” to be miles away from the site in question, recording the voiceover in a field outside London, surrounded by electricity pylons.

The half-hour TV documentary Hackney Marshes, commissioned by the BBC, was Smith’s first foray into the more conventional documentary space. True to form, he took the opportunity to both satirize the sincere BBC social-issue documentary and create something both more playful and more profound. In the film, about an East London council housing estate, Smith eschews documentary conventions—the talking-head interviews, didactic voiceover, illustrative images, clear context, and linear narrative—and uses the same elements to reconstruct a fragmented, digressive, and contradictory narrative through snatches of interviews with residents, sometimes seen on camera, sometimes only heard as disembodied voices; empty rooms in the estate; and seemingly irrelevant meanders through the expansive football pitches nearby (which, we learn, sit on top of marshes filled with rubble from the Blitz and covered with grass). When people do appear, Smith tends to treat them as part of the scenery; in an early scene, Smith abruptly cuts from a shot of a man telling him about life in the estate to the exact same shot but without the man, directing our attention to the room: the faded green couch, the tasseled lamp, the off-white wallpaper.

Smith’s structuralist, analytical, yet ironic approach is clearest in a small section a little over halfway through the film. In a move reminiscent of Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970), Smith turns away from the estate and the marshes to focus on letters and numbers found on goalposts and apartment doors and uses them to pun on the disembodied voices we hear over top of the images—for instance, when somebody says there have been 14 burglaries, the camera shows the door of apartment 14E.

Hackney Marshes documents the ambivalence surrounding the decline of the UK’s post-war social settlement on the eve of Thatcherism. While the estate’s residents appreciate the affordable housing, in some cases even emphasizing that it’s the first home they’ve inhabited with an indoor toilet, they also bemoan the estate’s crime and noise, its lack of community feeling, and the building’s dilapidated state. It’s also clear that there are social and cultural tensions between the estate’s working-class English and Caribbean residents. It’s easy to see how some of the viewpoints expressed in the film formed the underpinning of working-class support for Thatcher and, later, Brexit.

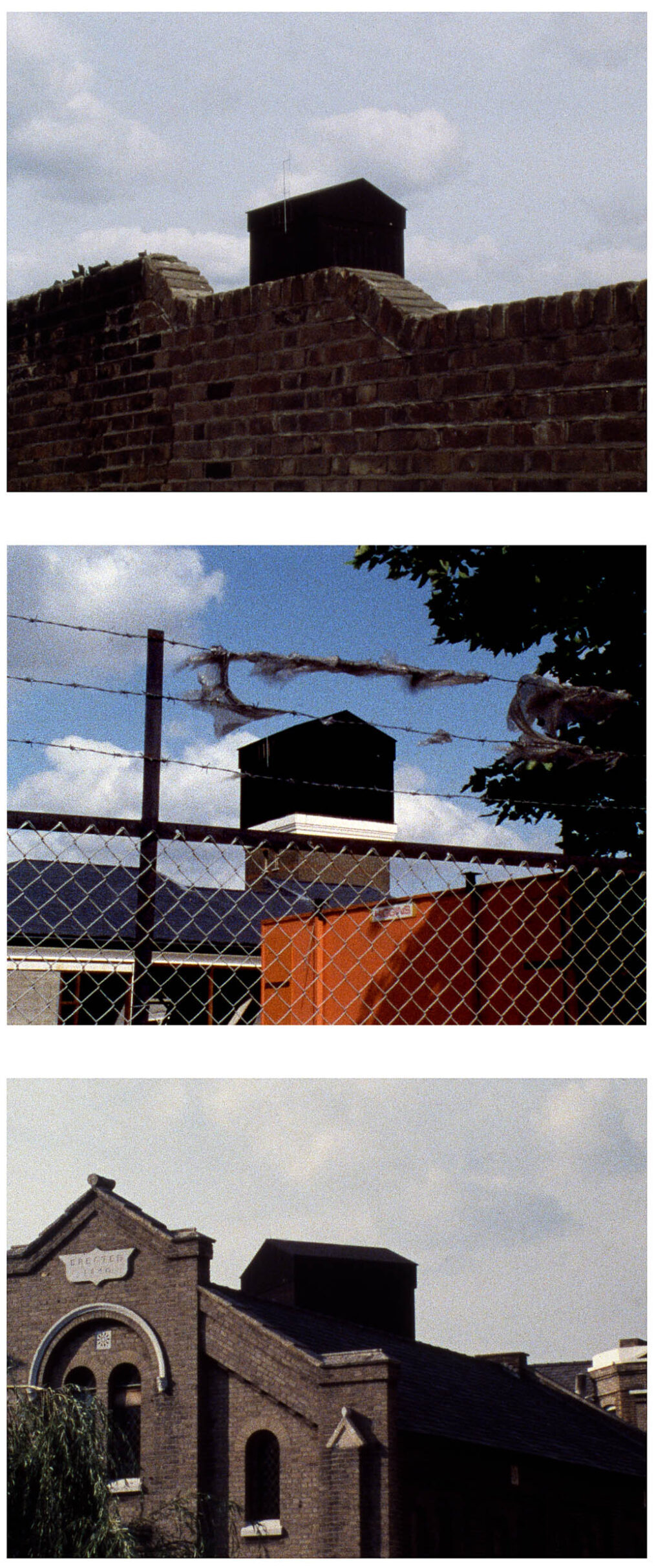

Formally, one could say that Hackney Marshes is partly about interactions between people, architecture, and politics. The Black Tower takes these interests further and fuses them with the insights into meaningmaking gleaned from The Girl Chewing Gum. In The Black Tower, Smith films the titular tower—actually the water tower at Langthorne Hospital— from various angles and invents a first-person narrative, presented in voiceover, in which the tower seems to be animate, alternately stalking the narrator around London and inexplicably disappearing. It is Smith’s most enigmatic film, which feels like a parable by Kafka or Borges or Poe. Is the tower a metaphor for mental illness? For death? For the burgeoning surveillance state? Whatever the case, it conveys a vivid mental state of obsessive and quixotic and ultimately hubristic curiosity vis-a-vis omnipotent and arbitrary institutions.

Blight, which documents the demolition of a stretch of Smith’s own Leytonstone neighbourhood to make way for the new A12 road that now links Hackney with the M11 highway, is both Smith’s most virtuosic and most heartfelt film. Just like similar projects across North America, including Toronto’s infamous Spadina Expressway, the A12 development was resisted by a wave of anti-highway activism, citing concerns about displacement and gentrification and all the rest. Though he lost his home in the development, Smith was only marginally involved in this protest, which was, as the film makes clear, unsuccessful. His role is that of the bemused spectator, not the activist.

Like many of Smith’s films, Blight generates new meanings out of cells of sound and image. The film begins with shots of houses seeming to fall apart of their own accord; only gradually do the workers demolishing the houses begin to be shown, revealing that what seemed like a natural (or supernatural) process is in fact human and political. Concretizing this theme further is the image that inspired Smith to make the film: a poster for The Exorcist on the wall of a half-demolished house.

Threaded through the film is an association between a woman’s voice repeating the phrase “Kill the spiders;” a tattoo of a spider’s web on a worker’s arm; and a web-like road map of London. It gradually transpires that the woman saying “Kill the spiders” was telling a story about her father having to kill the spiders in the toilet before she could use it. In a concrete sense, the spiders were an unwelcome infestation in the woman’s life; in the figurative sense that Smith invites us to consider, the residents of the demolished houses are the spiders that need to be eradicated to enable London’s top-down infrastructural development.

Unusually for Smith, the film is set to music, an eloquent “Different Trains”-esque soundtrack by composer Jocelyn Pook that complements Smith’s language by harmonizing snatches of speech with emotive strings. The cumulative effect of Smith and Pook’s fugue of ambiguous vocal and visual imagery is both wry and moving. As with The Girl Chewing Gum, Hackney Marshes, and many of Smith’s other films, Blight is unconcerned with taking a definite stance on the processes of gentrification, development, and displacement: It seeks instead to crystallize the perspectives and emotions involved.

If Blight represents a sort of apex of Smith’s artistry, demonstrating the almost symphonic or mock-epic effects to which his formalist and documentary processes could be harnessed, The Hotel Diaries is a departure that may, in an admittedly odd way, be his most accomplished and is certainly his most prescient film. In this series of films, which are almost like vlogs avant la lettre, Smith records hotel rooms in single, uninterrupted handheld takes while he muses, apparently unscripted, about the news of the day, his recent experiences, and other banalities. Though he touches on many topics, the films centre primarily on the war on terror and the related Israel–Palestine conflict, media complicity in manufacturing consent for it, and the cozy relationship between Tony Blair and George W. Bush.

There is little in the experimental canon, even among diary filmmakers, that is quite so guileless and transparent and improvisational and downright uninterested in aesthetics. Today, the visual culture of Zoom and vlogs, in which visual and vocal imperfections are signs of intimacy and honesty rather than unprofessionalism, is such that The Hotel Diaries feels natural. The film feels like a sort of companion piece to Eliot Weinberger’s classic London Review of Books article “What I Heard About Iraq,” in which he dryly recounts state and media messaging about Iraq as it filtered down in piecemeal propaganda soundbites to the truth-deprived public. Smith does something similar, cataloguing his perceptions and thoughts on the war and, in so doing, reflecting on the propaganda apparatus in which he—and we—were embedded.

Though the series concludes where it began, in Cork, Ireland, the climax (if such a term applies) occurs in Palestine, where, even in such close proximity to the victims of imperialist aggression and having to confront some of its violence himself at the area’s infamous checkpoints, Smith recognizes his privileged position as a white, British, male artist: Even in the same physical space, there is an insurmountable gulf in subjective location, imposed by imperial will.

The prescience of Smith’s aesthetics becomes clear again in two of his most recent films, Citadel and Covid Messages (2020). For most artists, addressing the COVID-19 pandemic required some shift in method; for Smith, having worked in isolation, critiquing society and technology from his bedroom window or the streets of his neighbourhood, it required only the slightest one.

Citadel is shot entirely from Smith’s window during the pandemic lockdown and shows a picturesque view of the City of London, the UK’s financial centre and its real seat of power, paired with fragments of speeches by then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing buying, selling, and blithely going about “business as usual”—and not, for instance, health—as the basis of human society. It picks up themes from The Black Tower and Blight: Buildings seem to come alive, whether through lights flickering mysteriously in windows or through the City’s inanimate skyscrapers made to loom out of the fog in sync with Johnson’s exhortations to “buy and sell.” It also picks up themes from Blight and Hotel Diaries: Here is a film that could not be more domestic and yet manages to address systemic issues that affect entire societies.

Covid Messages, for its part, parodies Johnson’s blustering rhetoric by forcing him to repeat words and phrases that quickly became COVID-era clichés—”hands, face, space”—and juxtaposes Smith solemnly singing “Happy Birthday” to a mournful tune with Johnson, seemingly boring himself at the podium, instructing Brits to wash their hands with soap and hot water for the length of time it takes to sing “Happy Birthday” twice. Smith is, as ever, immaculately unimpressed with this sort of brashness and pomposity and employs Martin Arnold-esque techniques to poke fun at it all.

It’s in this borderland between the serious and the comic, the real and the imagined, the personal and the political, the structural film and the documentary, that Smith’s work stakes a claim to something uniquely Smithian. His formal ingenuity, while aligning him with structuralist filmmaking, transcends the merely formal experiment—his work is always anchored within a milieu, itself constantly changing, subject to forces that menace it from above like the titular black tower, while Smith remains in the centre, observing from a constant vantage point.