In one of the more emotional moments—and there are many—in Peter Raymont’s often-shattering Shake Hands with the Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire (2004), Canadian General Roméo Dallaire recounts his rage at Belgium’s withdrawal of its troops in the early days of the Rwandan genocide. This led to the departure of 2,500 UN troops that could have been used to stop the ensuing slaughter of 800,000 people in the next 100 days. Yet 50 years earlier, while Dallaire’s father and other Canadian soldiers were fighting and dying in Belgium to free it from Nazi occupation, Belgian troops remained in Rwanda, protecting and exploiting their country’s colonial resources. “The perverseness of that is just beyond me,” Dallaire exclaims.

Given the unifying theme of this issue concerning the documentary as Canada’s true contemporary art form, it’s worth reminding ourselves of Joyce Nelson’s keen observation from her book The Colonized Eye: Rethinking the Grierson Legend that “one significant aspect of Canada’s ‘national tradition’ was entrenched colonization by old and new empires.”

Canada is a country with colonialism in its DNA, a fact that has seldom been more apparent than during times of war, constitutional crises or conflicts with Indigenous peoples. Surveying the vast canon of Canada’s films about war offers not only a history of the documentary form’s evolution, but also of this country’s sometimes traumatising maturation from a child of empire struggling to assert itself, to an independent society struggling to reconcile its own internalised colonialism in its relationships with different marginalised groups.

But words like colonialism and empire mean different things to most Canadians today than they did nearly a century ago. As Nelson further explains, before the start of the Second World War John Grierson had already “changed the connotation of the word ‘empire’ to a more palatable-sounding and modernist expression. That ‘international combine of industrial, commercial and scientific forces’ was central to his wartime work in Canada.”

Stuart Legg’s Churchill’s Island (1941), from the National Film Board’s wartime series Canada Carries On, exemplifies this view. A highly effective work of propaganda, this inaugural winner of the Academy Award for documentary short showcases remarkable editing and a highly persuasive mix of journalism, jingoism and entertainment. Lorne Greene’s stern yet bombastic narration presents a rousing narrative—“The greatest machine of conquest of all time versus the white ramparts of Britain!”—that would have stirred the hearts of English Canadians back then. The film still conveys a palpable sense of urgency and immediacy, of being on the brink of a breaking point in human history. And Canada Carries On proved to be a popular series in the U.S. and Canada, establishing the NFB as a key documentary producer.

Films that would follow in the post-war period present both the First and Second World Wars as “a second-hand, archival-based event, filming not the history or the legend but the archive,” as Seth Feldman argues in his 2014 essay ‘The Kid Who Couldn’t Miss: Documentary, Iconography and Memory Up in the Air.’ Canada at War (1962), a 13-part series produced by the NFB for broadcast on CBC, strains to emphasise Canada’s new, grown-up status within the empire—free to move out, but still living at home. “For the first time in war, Canada was constitutionally free to set her own sail,” it declares. But nevertheless, “a recorded vote was not taken and Parliament asked the King to speak for Canada.”

Churchill’s Island, Stuart Legg, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

The series clips along at a brisk pace that would not seem foreign to contemporary viewers, offering a broad chronological overview of events punctuated by fascinating historical asides. Many elements echo loudly and disturbingly into the present, such as the statement that “Each democratic country had its fascist superman and his twisted following,” as well as Mackenzie King’s description of Adolf Hitler as “a simple sort of peasant, not very intelligent, and no serious danger to anyone,” and footage of Poland “being wiped from the map,” which bears eerie similarity to recent atrocities in Aleppo.

Many of the towns and villages featured in Donald Brittain’s 1963 NFB documentary Fields of Sacrifice still bear the scars of those battles—the pockmarked walls and collapsed husks of blownout buildings and churches. An associate producer and editor on Canada at War, Brittain takes a more poetic and lyrical approach here. Although the film at times risks becoming a montage of headstones and cenotaphs, it conveys a sombre, proud and pensive tone as it visits battle sites where Canadian soldiers fought and died in the First and Second World Wars (but not, perhaps egregiously, Korea).

A thriving cottage industry of First and Second World War documentaries has continued to evolve from this modernist vein. Significant examples include: the NFB/CBC’s Gemini Award-winning documentary miniseries The Valour and the Horror (1992); Breakthrough Entertainment’s For King & Empire: Canada’s Soldiers in the First World War (2001) and For King & Country: Canada and the Second World War (2004); and many of the fine works produced by Toronto’s YAP Films, such as Battle of the Somme: The True Story (2006), Vimy Ridge: Heaven to Hell (2007), Camp X: Secret Agent School (2014) and Black Watch Snipers (2016). These works mark an evolution in form from the classical educational style to using docudrama, narrative elements, and reality-TV-inspired searches to solve mysteries of the past. In general, they seek to probe, yet ultimately preserve, the legends of Canada’s wartime contributions.

The Kid Who Couldn’t Miss, Paul Cowan, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

A film with a different modus operandi altogether is Paul Cowan’s The Kid Who Couldn’t Miss (1982), a controversial docudrama of legendary First World War flying ace Billy Bishop. Consisting of excerpts from John McLaughlin Gray and Eric Peterson’s stage play Billy Bishop Goes to War, intercut with interviews with some of Bishop’s colleagues and at-times fictionalised (or just terribly researched) accounts of Bishop’s exploits, the film drew fierce criticism for claiming that Bishop’s record of 72 kills was fraudulent, and that he’d lied about a raid on a German aerodrome that earned him the Victoria Cross.

Perhaps coincidentally, The Kid Who Couldn’t Miss came out the year that Canada patriated its constitution and pirouetted to only a step removed from the British Empire. Following a parliamentary review of the film’s questionable veracity in 1985, the NFB was forced to insert a disclaimer at the beginning of the film declaring it “a docu-drama [that] combines elements of both reality and fiction.”

One thing The Kid Who Couldn’t Miss has in common with the films above is its ability to convey the sheer carnage and trauma of war. Bishop’s record of 72 kills was so astonishing in part because the average life of a pilot in France was only 10 to 20 days.

In telling the story behind “the most quoted…and for many, the most moving” words ever written about war, Robert A. Duncan’s John McCrae’s War: In Flanders Fields (1998) recounts one of the most heinous episodes on the Western Front: the chlorine gas attack at Ypres on April 22, 1915. Some soldiers fired into the haze in desperate confusion. Others shot themselves to end the agony. Major John McCrae, a veteran of the South African War and an accomplished poet, described the fallout from the attack as “17 days of Hades… For 17 days and 17 nights, none of us had our clothes off… [G]unfire and rifle fire never ceased for 60 seconds… None of our men went off their heads, but men in nearby units did. And no wonder.”

John McCrae’s War: In Flanders Fields, Robert Duncan, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

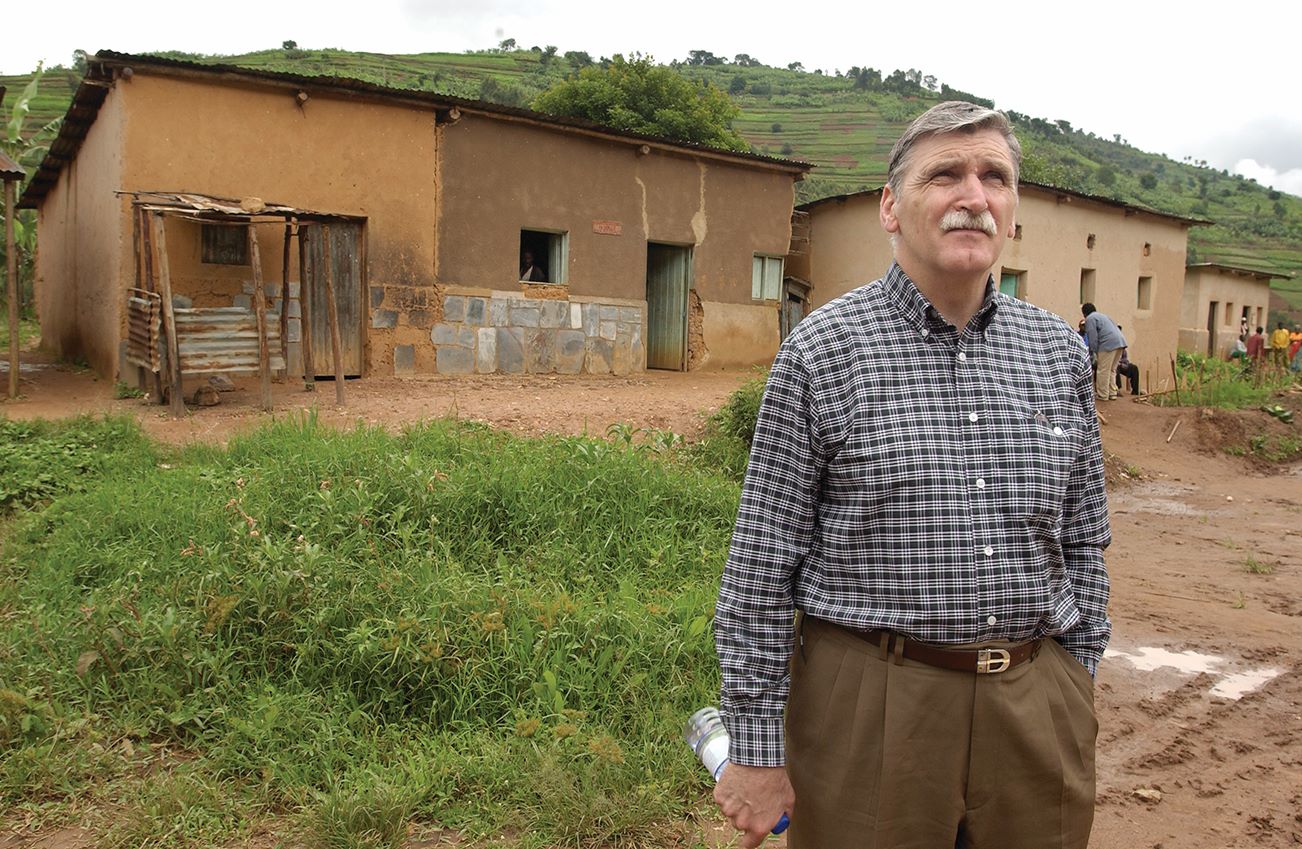

Less than two weeks later, McCrae sat down to write “In Flanders Fields” following the death of his friend, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, who was literally blown to pieces by an artillery shell. McCrae supervised as soldiers collected bits of Helmer into burlap sacks, molded them into the shape of a body, and then buried it. In Shake Hands with the Devil, Roméo Dallaire recounts how the streets in and around Kigali, Rwanda, were littered with “so many bodies we couldn’t pick them up.” Driving through Rwanda for the first time in 10 years, he says, “I see the difference but I can’t get the past pictures out. They keep exploding in front of [me]. Really, really clear. And in slow motion.”

Shake Hands with the Devil demonstrates with painful clarity how war cannot be separated from the political machinations that precede it. The mandate of Dallaire’s “hopelessly underfunded” peacekeeping mission, which was so cash-strapped they could barely pay for phone calls to New York, was “literally witnessing the mass slaughter of human beings.”

“The whole [peacekeeping operation] was a bluff,” Dallaire explains. “It was just a huge bluff, because I had no capability of controlling the [demilitarized zone] at the time… It was like watching a fuse burn into a powder keg…and finally there was an explosion.”

Action: The October Crisis of 1970, Robin Spry, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

One of the most famous powder kegs in Canada’s history, the October Crisis of 1970, illustrates how the field of politics can often morph into a battle, and at times result in casualties. Robin Spry’s gripping 1973 doc, Action: The October Crisis of 1970, begins by recapping the colonial wars that created Canada and describing a Quebecois population that is “rural, subjugated and poor…shaking off the cobwebs of centuries of isolation” to confront “the powers which controlled and exploited Quebec… Here was the beginning of real social upheaval. The people of Quebec saw that change was within their grasp.”

But the grasp of the Quiet Revolution turned from open palm to closed fist in the hands of the FLQ. Between 1963 and 1969, the “100,000 revolutionary workers, organized and armed,” as the FLQ described itself, bombed more than a dozen national and federalist organizations, including the Royal Canadian Air Force, RCMP headquarters, Eaton’s, City Hall, the Montreal Stock Exchange and Mayor Jean Drapeau’s residence. Six people were killed in seven years. Subsequent mining, labour and taxi strikes resulted in riots, bombings and more deaths. When the Parti Québécois won 24% of the popular vote in the 1970 provincial election but only 6% of the seats, many in Quebec were left feeling “that the democratic process no longer works.” The Ministry of Defense was bombed, and within days James Cross and Pierre Laporte were kidnapped.

After Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act at 4 a.m. on October 15, Spry explains, “Hundreds of astonished and outraged people find themselves abruptly taken from their homes in the dead of night and imprisoned. These people will discover…that under the War Measures Act, they can be kept in prison for up to 90 days without a trial, and that being a member of the FLQ has suddenly and retroactively become a crime, punishable by up to five years in prison.” In a televised statement, Trudeau attempted to explain his methods and ensure Canadians that, “I find them as distasteful as I’m sure you do.” Ontario premier John Robarts, meanwhile, “announced that Canada was in a state of total war.” 300 people were imprisoned in two days.

René Lévesque’s incredibly articulate response to news of the assassination of Pierre Laporte concludes with the pledge that the Quebecois would “continue to develop, and we hope we take a lesson out of this about the price of human life and making it livable. But that’s our responsibility. No one should think this is an excuse to make Quebec a jail.” Joyce Nelson echoes this attitude towards sovereignty in The Colonized Eye: “A people can have no national identity if they have no collective, boundaried claim to their own territorial ground. Colonization in its deepest, psychological sense is precisely the prevention of such identity and identified claim to place.”

That statement could just as easily be a line of narration from any film by Alanis Obamsawin, particularly ones that examine the abusive nature of Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous peoples, such as Kanehsetake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), Rocks at Whisky Trench (2003), Trick or Treaty? (2014) and the rhetorically titled Is the Crown at War with Us? (2002).

But perhaps the best example of such abuse is the dark legacy of Canada’s residential schools, which were made mandatory for Indigenous children in 1920 and ended with the closure of the final school only 21 years ago. When discussing the 133-year history of these schools (perhaps “camps” is more appropriate) during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Justice Murray Sinclair cited Article 2(e) of the United Nations definition of genocide, which includes “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

This experience of being taken from one’s family—often at the age of four, not to return until at least 16—is wrenchingly remembered by the subjects of Rhonda Kara Hanah’s pioneering television documentary Sleeping Children Awake (1992), produced through Lakehead University. “The Mounties came and got us,” one elderly woman remembers. “We were playing in a tent and they just put us in a car and off we went.” Artist Ernie A. Kwandibens describes how “I used to wait in bed for my mother to show up. But she was never there. She was a couple hundred miles away. I couldn’t realise the distance that I had travelled by train. I thought my mother was just where the truck picked us up, where we got off the train.”

Perhaps the earliest film to document Indigenous survivors’ experiences, Sleeping Children Awake — which won the 1993 CANPRO Award for best documentary and screened as a form of public testimonial during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission — also draws on actor and playwright Shirley Cheechoo’s play, Path with No Moccassins. “When I got to residential school,” Cheechoo explains in the film, “everything was taken away from me: my sexuality, my culture, my language, my family. It’s like being put in a box and you can’t move.”

The numbers bear out the reality of residential schools as a battleground for generations of Indigenous people; the fatality rate for children in residential schools (approximately 6,000 out of 150,000) was the same as for Canadian soldiers in the Second World War (approximately 44,000 out of 1.1 million).

Survivors speak of regular physical, sexual, emotional and spiritual abuse. Echoes of the Holocaust are not hard to find. “We had numbers” instead of names, one woman explains. “I was 5. My sister was 8. That’s what we called each other; hardly ever by names, just by numbers.” Another remembers passing a cookie to her brother as they passed in the hall every Sunday—the only time she would see him. She couldn’t talk to him, as speaking their language was forbidden. “I can remember kids coming in from Moose Factory and way up north, little children,” another woman recalls. “And they couldn’t speak a word of English. And as soon as they went to speak their language they got whippings and strappings. They take away everything from you in there. They deprogram you. They try to turn you right into a white person.” Another survivor concludes that, “The most powerful unspoken message that was there constantly was just be like us and everything will be okay.”

Like the “entrenched colonialism by old and new empires” that the idealistic Dallaire witnessed in Rwanda, the forms of colonialism within Canada, and the many moving documentaries that have chronicled its effects and evolution, carry lessons that can either be heeded or repeated. “History will teach you many things.” British Columbia Vice-Chief Bill Wilson says in Kanehsatake. “But you’ve gotta listen.”