When the Governor General’s Award-winning filmmaker, editor, writer, mentor and co-director of Manufacturing Consent Peter Wintonick died in November 2013, it was a devastating blow to the international documentary community, which had embraced him as “Canada’s documentary ambassador.” Peter died in Montreal during both the RIDM (Rencontres Internationales du documentaire de Montréal) and IDFA (International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam) festivals, where his passing was occasioned by outpourings of grief and tributes, which continued for more than a year. (POV #93, Spring 2014, which I edited and contributed to, was entirely dedicated to Peter’s immense talent and career.)

Peter’s death was also a tragedy for his wife Christine and daughter Mira. When it was all over, it was left to Mira to take on the task of creating a suitable film to portray him one last time. With the help of Montreal’s acclaimed independent producers at EyeSteelFilm, Mira was supported in her endeavour to make a documentary about a famous documentarian. The result is Wintopia, a startlingly apt juxtaposition of footage shot by Peter with a soundtrack created by Mira following a daughter’s quest for her father while he’s on a lifelong search for utopia.

Mira is an award-winning audio producer, story editor, and documentary filmmaker. For a decade, she produced the absurd and poignant comedy show WireTap with its creator Jonathan Goldstein for CBC radio. Presently she is the senior editor and co-creator/producer of CBC’s Love Me about, as she puts it, “the messiness of the human condition.” Wintopia, an EyeSteel/ NFB co-production, is Mira’s first solo feature documentary; she had previously collaborated with her father on Peter’s last feature, pilgrIMAGE.

Mira Burt-Wintonick spoke to POV editor Marc Glassman at the 2019 IDFA festival, where Wintopia premiered.

— MARC GLASSMAN

MBW: Mira Burt-Wintonick

POV: Marc Glassman

POV: How did Wintopia begin? My memory of the time when Peter was dying is that he left the film footage for his Utopia project, about his life-long search for a paradise on earth, to you as one of his last wishes. I don’t even know how formal it was. Did he tell you that he wanted you to finish Utopia?

MBW: Before he died, Pete wanted us to make a film together about his life and his work. After he passed, I remembered that we had these “utopia” tapes in the basement. They were from the unfinished film he had been talking about for years. I thought, how do I make this film portrait of his life when I don’t have any material for it, other than his writing and interviews here and there?

I had never seen the utopia footage, so I was curious about it, and I thought it would be a nice metaphor for his life. It stands in for all the other films he did make, all the other things he was trying to accomplish. So, even before I’d seen it, I thought, let’s use that footage and create a portrait of him through that. I dug it out of the basement.

There was one box filled with tapes, but there were other boxes that said “utopia” on them, which were filled with papers and research from all his travels, or newspaper clippings, or maps from these road trips he was on, looking for different utopias. And in those boxes, sometimes I’d find spare tapes as well. And in other boxes of tapes from his previous films, I would notice more utopia tapes. In the initial box, there were maybe 200. Then, once I gathered the rest of them, the stray ones, I would say there were almost 300 tapes.

POV: Can you tell me about the editing process?

MBW: I didn’t put that much of myself into the story in my first draft of the film. I was trying to make his utopia film. I would do research, say, of Christiania, a squatter’s commune in Copenhagen. Pete had a few hours of footage following a tour guide there, so I researched the place and tried to figure out what had drawn him there. I was narrating the film more or less traditionally at this point. We even had archival footage we’d tracked down to finish the story because his footage wasn’t complete. It was usually a couple of hours of him wandering around, but not much that explained why you were there. It was mostly made up of those kinds of scenes, with little bits of home movie footage in between.

Some of my own process of going through the grief was in there, but the balance was skewed toward utopia as a topic. It became clear, after I did that first pass, that anyone could make a film about utopia, but I should try to make the film that only I can make, a film about our relationship—Pete’s and mine—and the grieving process. I let go of a lot of the utopia information to focus on that.

POV: It becomes, in a way, your quest to figure Peter out.

MBW: Yeah, to figure out his quest.

POV: When did EyeSteelFilm — Dan Cross, Mila Aung-Thwin, and Bob Moore —get involved?

MBW: They were involved from the beginning. They were going to help him make his final film, when he was still alive. They were going to be involved, helping to coordinate, raise money—whatever was needed. As soon as he passed away, they didn’t hesitate at all. They took me on. They gave me a little edit room to camp out in and watch the tapes, and left me alone for the next year, which is what I needed, to not be bugged. Not alone. They were supportive, but they didn’t pressure me. Like, “When is it going to be done?” or, “We need to start raising money for it!” They were helping me apply for grants, and things we needed to do, but they let me take the time I needed with it, which was the most supportive thing they could do.

POV: And were you bouncing ideas off your mom [Christine Burt]?

MBW: A little bit, but not too much. She watched a couple of earlier cuts of the film. I think she was pushing me to make it more of a portrait, like a bio film of him, to try to capture more of his ideas. At the same time, she was supportive of how it was such a personal film for me, and it needed to be made that way. She allowed me to process my feelings and make it the film I needed it to be, even though, I think, for her, at least in the earlier drafts, she would’ve wanted it to be more of a celebration of all his accomplishments.

For me, it needed to be a more honest portrait of the complexities of his life, and of our relationship. That was the truer story, and I think it’s the better story. It’s not just to paint a glowing portrait of someone where there was no tension. There was a lot of tension in his life, as there is in all our lives. We’re flawed, we’re trying our best, but we don’t always do that well. Now Christine loves the film. She sees all these poetic details in it that I didn’t even intend. She’s really happy with how it turned out.

POV: What was your process in turning the film into what it has become? Did your understanding of Peter evolve?

MBW: I wanted to really immerse myself in the process of watching the footage, and to immerse the viewers in the process of watching this footage, and of what it’s like to have these very limited archives of someone’s life after they’re gone. When someone’s gone, you don’t get any new moments of them. But here, going through these boxes, I was getting new moments. I also wanted to get some insights and understanding from his friends and collaborators by interviewing them. Some didn’t make it into the film, but they still helped. It gave me a greater understanding of him, as I was making it. Even if their voice isn’t in the film, they still were helping me get a sense of what he was up to when he was away.

I think my mom and I kind of knew what he was doing in an abstract way but I didn’t quite grasp until after he died how much he was actually impacting people, and what his presence meant to the documentary community—how many films he helped get made, or helped to turn into better films. So, in the process of making the film, and coming to terms with the fact that he was often away and didn’t spend that much time at home, which I resented while growing up, my new understanding of how much impact he was having did make it feel worthwhile, or more understandable.

POV: Editing is a key part in making any kind of documentary and, for you, it must have been crucial since you were relying on archival footage mixed with new audio. Can you talk about creating the narrative for Wintopia?

MBW: We had to weave three films together: a film about utopia, a film about a filmmaker, and a film about a father-daughter relationship. It was very tricky. I don’t even know how many drafts I went through. All editing is like putting a puzzle together, where you don’t have a picture of what the puzzle is supposed to look like, and there are no edges, and there are pieces missing, and there are pieces that are three-dimensional, and five-dimensional. You don’t know how they fit in! I spent a lot of time just trying things, trial and error.

At one point, I brought in Anouk Deschênes, who is a young film editor in Montreal. I had been working on it, at this point, for almost five years, on and off—I was doing radio stuff on the side. I was feeling very isolated in this dark editing suite, because it’s a very emotional experience to watch footage every day, to be thinking about my dead dad every day in this challenging way. So, we brought Anouk in so I could have someone to bounce ideas off of, who I could talk things through with, which turned out to be very helpful, to not be alone. Even though it’s such a personal film, I needed someone to get in the weeds with me. And she didn’t know my dad, so it was helpful to have an outside perspective, too. We wanted the film to be one that would be worth watching for someone who doesn’t know my dad, who could get drawn into the story of a daughter trying to connect with her father. She had edited Manic, another EyeSteelFilm, also about a daughter searching for clues from her father. She turned out to be the perfect person.

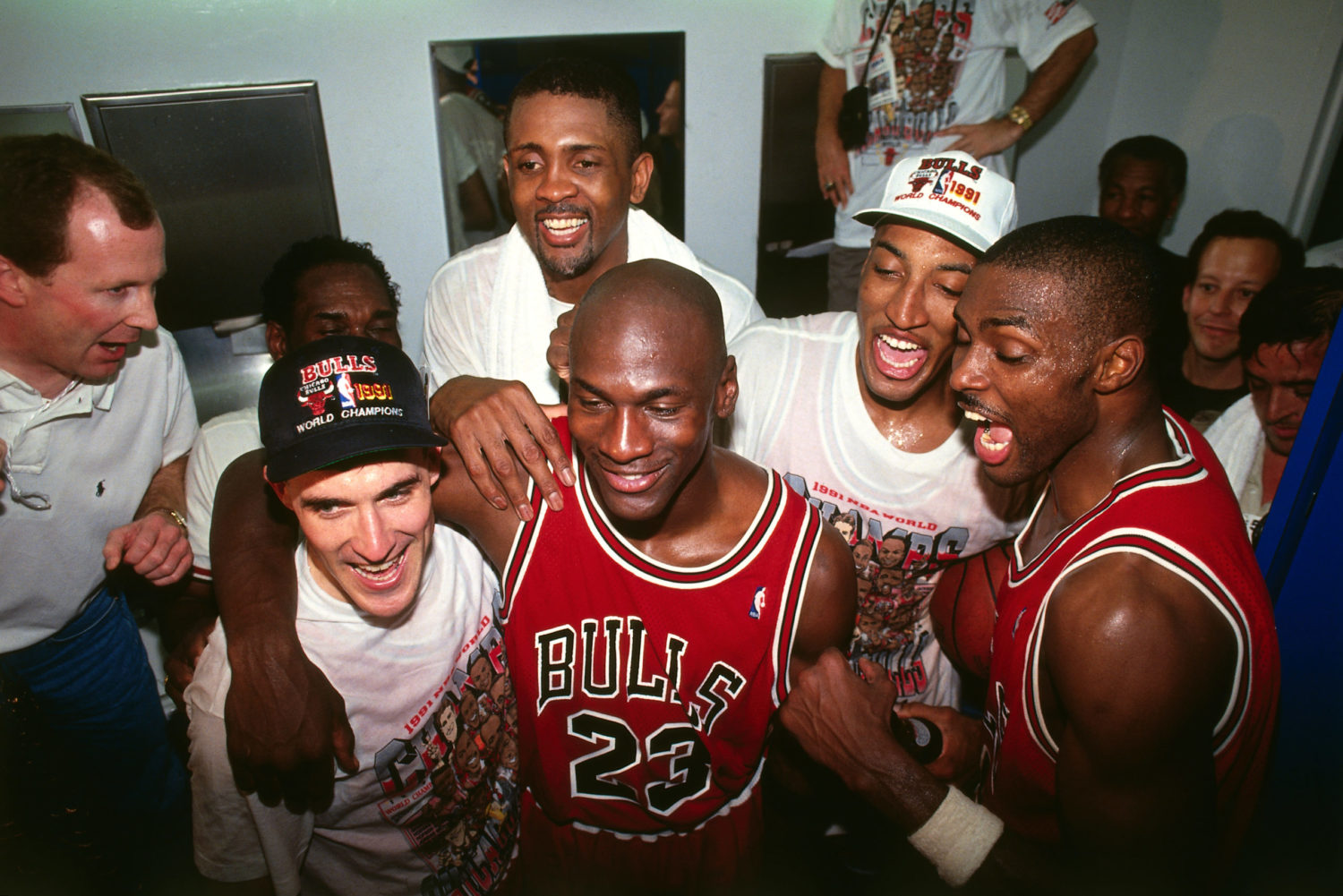

I wanted to be very hands-on but I also needed someone to help me process things. The clips of Pete’s films that I use in Wintopia, they’re always characters in the films talking about their dreams for the future. Noam Chomsky, for instance: the clips I use from Manufacturing Consent are after someone asked him, “What’s your vision of an ideal society?” He said, “Somewhere where we would be seeking out forms of authority and challenging their legitimacy.” And in The Street, it’s a clip of Dan Cross asking one of the characters in the film, “What are your hopes for the future? Are things going to change? Are they going to get better?” And he says, “Yeah, I hope they get better. I haven’t really thought about it.” I wanted to have all the clips tie into the utopian ideas. The only times we leave the utopia footage are for home movies or for his filmography clips. The clips had to show his editing, his skill, his career, while also highlighting the utopian aspects.

POV: You’ve worked on radio since you were at Concordia. Your work on the CBC’s WireTap with Jonathan Goldstein was a big hit. What are the differences between working in radio and film?

MBW: Through audio, I have fourteen years of story editing experience in terms of crafting documentaries, and fiction, and hybrids. They’re shorter forms. That was the new challenge for me. It wasn’t doing film versus radio, it was more doing a feature, ninety minutes versus a half hour, which is how long my radio documentary work has been. That was a challenge. But the actual story, structuring the story—every time you approach a new story it feels impossible, like you’ll never figure it out no matter how much experience you have! At the same time, I trust my instincts to some degree, now, from my radio work.

POV: You took off quite a lot of time away from the film while you were making it. What happened?

MBW: I had another editor at first, Catherine Legault. She had edited pilgrIMAGE. I had worked with her before. She helped me the summer after Pete died, watching the film. We threw together the first assembly. I was in such a state of shock. It was helpful to have her there with me. Just to show up to the office—I had to show up because she was there. It forced me to start doing something. It was good and bad. I don’t know that I needed to start that soon. But it helped me not to put it aside at the very beginning. After that first assembly, I worked on it a bit on my own, and then I took a year and a half where I didn’t look at a single thing. I didn’t watch the rough cut. There were no new tapes. I didn’t look at anything. It was about two years before I came back to the tapes again, with fresh eyes and was ready to deal with it again. I think it was so helpful. When I came back to it after that break, I thought, this isn’t the film I need to make at all. I need to make it much more personal. The luxury of time is so crucial.

POV: I was surprised at how little we hear Peter talking about utopias in Wintopia.

MBW: It’s one thing that was a bit disappointing when I got the tapes. I thought I would have this box full of material of my dad on camera—I was hoping. When we did pilgrIMAGE together, he was doing all these little video diaries on camera. I thought that’s what I would have, hours of him talking, doing little speeches off the cuff. There’s very little of that in the Utopia footage. Mostly he’s filming fields, buildings, and I don’t know why he’s there. What does this have to do with utopia? Why are you filming this building, or this street? In my grief, that was a disappointing thing, not to get so much of his voice and his ideas. But then, the moments where he turned the camera on himself were so precious, because they were so rare.

POV: I would say to Peter, a lot, “You’re such a colourful personality, why don’t you put yourself in front of the camera more?” He would say, “No, no. That isn’t what a documentarian does. I don’t want to be like Michael Moore.” Honestly. It was kind of a struggle for him.

MBW: That’s funny. He had those two polar sides to him—larger than life, comfortable in front of the camera, riffing and performing, but then also very shy. He had a quiet, hidden side.

POV: It’s very moving, seeing footage of you as a kid relating to Peter. Do you have many home movies?

MBW: There weren’t tons. There were two road trips. There’s one when I’m about five. I don’t think we drove across Canada, but we took a long trip, and there are a few tapes from that. And then, there are tapes when I’m about 12, where we drove from Montreal to Vancouver, so there are hours of footage from that trip. And then, when I was older, there was pilgrIMAGE. But there was nothing in between.

POV: There’s not much in Montreal, I noticed.

MBW: No. There’s one, a tape I didn’t use, a birthday party. Most of the tapes are travel footage. For me, they’re lovely to watch. I was so comfortable in front of the camera when I was five; we had a funny back and forth. You can hear him joke around with me from behind the camera, and I’m hamming it up.

POV: Making a personal film is difficult. You’re putting yourself out there for people to see. How did you figure out how to approach the film after that decision had been made?

MBW: There was still a process. How much of myself will I put into the film? It took a while to get to the stage of putting so much of myself into the film. I was kind of holding back and guiding the film through what I call “the other voices”—the sound pieces, the audio in the film.

POV: It must have helped that you had a radio background.

MBW: Well, yes. I treated the film as a “soundpiece,” with telephone conversations, sound and music. That’s where the story is happening, because the footage is kind of a blank slate since there isn’t much footage of him on camera talking. It’s mostly visuals with some moments of dialogue. It’s more of a visual collage with the story happening in the sound.

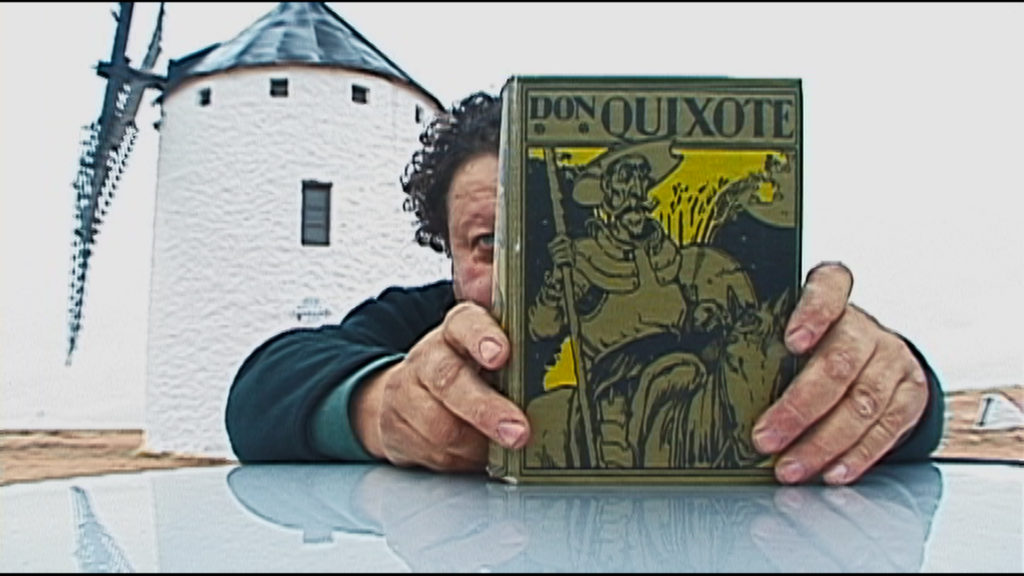

POV: I was very happy you found some Don Quixote footage. That was perfect.

MBW: There’s hundreds of windmills that he films, all over. There are a ton I didn’t put in. There’s literally a windmill on every tape he filmed. I felt like I had to represent that obsession.

POV: It does fit in. If there’s any conscious, physical location for utopia, it’s kind of La Mancha.

MBW: Exactly. To me there are two elements in the film: wind and water are heavily represented. The wind is the Don Quixote utopian quest, the windmills. Pete, in the opening of the film, is wrestling with the wind as it’s almost taking his map away from him. Then, at some point he’s pretending to be a windmill. He starts to control the wind. Then, the water: St. Brendan, the navigator, was the other symbolic guide of the film. He was an Irish monk in the sixth century who set out searching the seas for a physical utopia, paradise on earth. The symbolism of water, setting sail for this elusive island, somewhere hidden on earth. And these aren’t things I was trying to impose on the film. In the footage, there were tons of windmills, and there was a lot of water. Pete was drawn to these two things. They became my guiding characters in the film, Don Quixote and St. Brendan, people Pete was inspired by. I tried to use those two characters—maybe St. Brendan more explicitly, in the narrative. These utopian searchers that have come before Pete in fiction or reality, this common human quest for something better.

POV: How does it feel now, not just finishing a major work that’s emotional for everybody, but one that has been on your mind, and about your dad, for six years?

MBW: The day I finished the sound mix—when it was finished finished—I had a big cry. We had picture locked a couple of months earlier, but there was still the sound to complete. The day that it was actually finished, I had a big, complicated cry with all kinds of different feelings in it.

When Pete was sick, Christine and I saw him every day, and became so close to him, over those last two months. Then, he died, so we lost him again. But then we had this box of tapes, so there he was again! Just watching the footage for the first time was like spending time with him every day, even though, when he was alive, I wasn’t spending much time with him. It was this backwards reunion after his death. Then, getting to the end of the tapes was like another loss, another grief. The grief got delayed.

At the same time, there’s some relief that it’s done. It has been so hard, creatively and emotionally. I’m glad it’s done. I feel good about it. There are always things you could tweak forever. But I feel ready to let it go into the world, to share it with people and move on with my life, to do something else.

Wintopia screens next as part of the Hot Docs online festival beginning May 28 and DOXA beginning June 18.

Update (April 9, 2021): Wintopia is in digital release nationwide.

Visit the POV Hot Docs Hub for more coverage from this year’s festival.