“I hope that people want to go out and party, and that the film mirrors a club experience,” says Tramps! director Kevin Hegge. “I hope that energy of embracing good vibes is in the movie.”

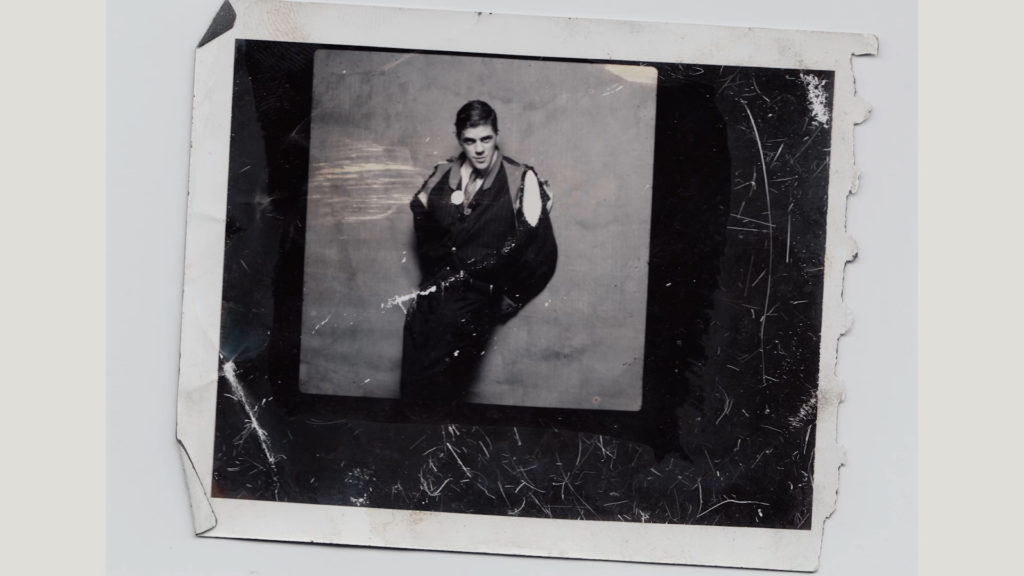

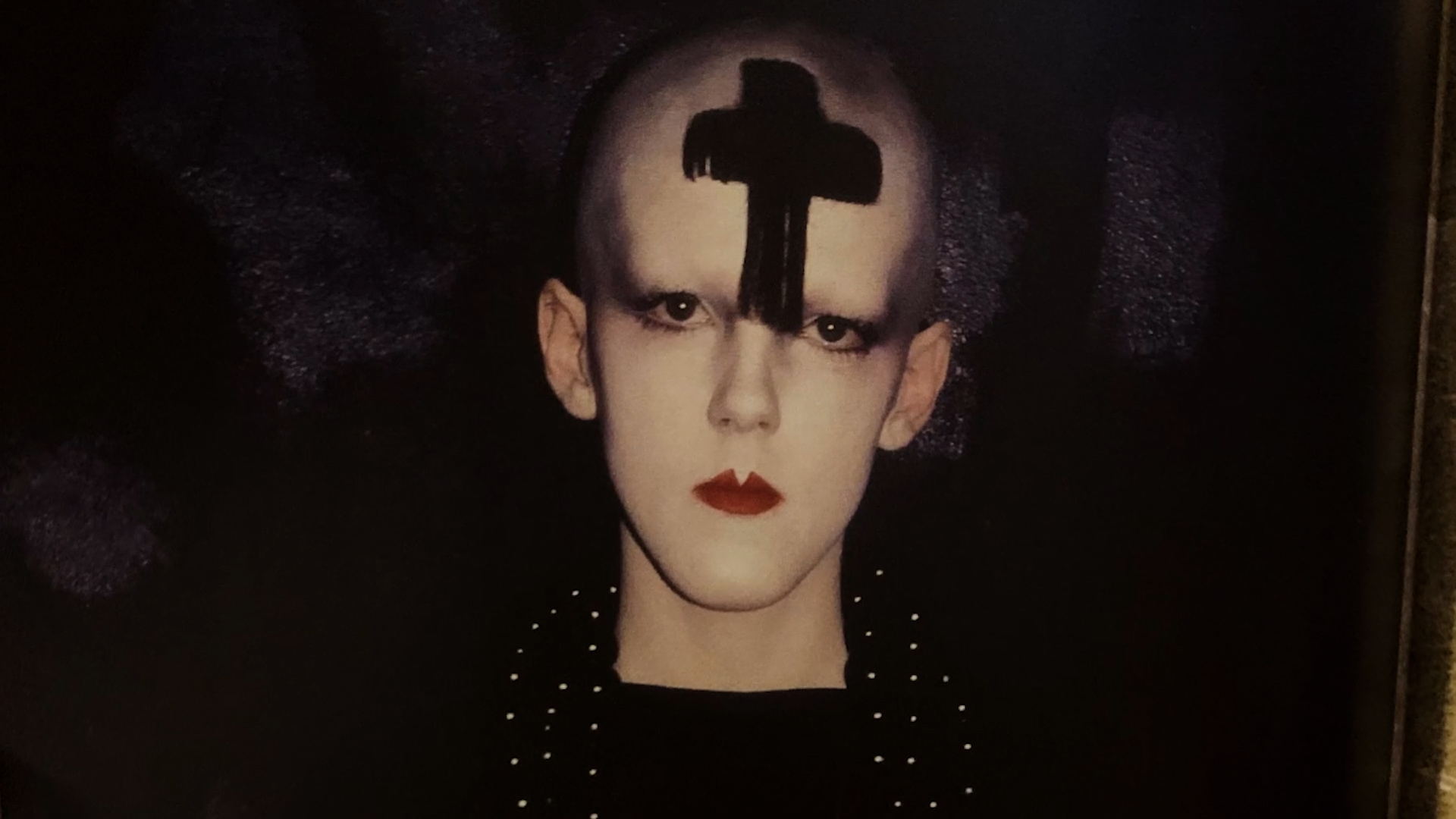

Hegge’s documentary Tramps! screens as the centerpiece gala at Toronto’s Inside Out LGBT Festival this week. Its hometown premiere offers an energetic call for audiences to reimagine the power of the city’s nightlife. Tramps! is a loud, wild, and scrappy portrait of the New Romantics, the countercultural scene that emerged in late 1970s’ London to unite outsiders, misfits, and bohemians. Figures from the era like designer Judy Blame, filmmaker John Maybury, DJs Princess Julia and Jeffrey Hinton, dancer Les Child, and nightclub promoter Scarlett Cannon reflect upon a movement born in London’s underground where people were free to experiment and fuel the city from the inside out. Style sirens all, these New Romantics—a term they resist, by the way—look back at a time when the artists starved but looked fabulous and when a raucous night out often meant wading through ankle-deep soggy toilet paper in the loos of London clubs.

Moreover, as the interviewees reflect upon the era, Tramps is less a time capsule than a portrait of immortal coolness. These veterans of the nightlife know how to stay young at heart, but as Tramps! weaves through the conservatism of the 1980s, the AIDS crisis, and the world’s gradual descent into boredom, the voices speak to the power of living in the moment without letting social pressures force you into a box. The film challenges audiences to look back at the clubs, concert halls, galleries, arty cafés and dive bars to recognize the shared spaces that are the life of every city.

POV chatted with Kevin Hegge via Zoom ahead of Tramps! premiere at Inside Out.

POV: Pat Mullen

KH: Kevin Hegge

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: When you were growing up in Canada, how much access did you have to some of the magazines, music, and fashion that we see in the film? How did you learn about this movement in London?

KH: I come from a family that collects music and is into records, so pop culture was prevalent in my upbringing. Towards high school, when I was finding out that a lot of men thought that Boy George was a woman, I just loved the trickery before I even really understood why—it was because I was gay! [Laughs.] My sisters were huge fans of the Duran Durans and the Boy Georges, and my era of discovery was what followed: the Björks and the Massive Attacks. I’ve always been a default Brit Popper too.

As I got older, I started discovering works by people like Michael Clark, the choreographer. I became a fan of him and it all started making more sense in terms of how it intermingled after this movie’s timeline ends. The work of these people is present in later pop cultural that I grew up on—I could see how Judy Blame did this, and Body Map did that, and Leigh Bowery did this, etc. I went backwards because magazines like The Face and i-D were pop cultural institutions by the time Brit Pop was around, so that wasn’t really an access point to the subculture by the time it reached me. It was more that I was an obsessive person digging through history.

POV: Boy George is present in the film even though he isn’t a speaker. What was the process of giving space to other people?

KH: Initially, I didn’t want Boy George in it. I love Boy George, especially as a personality—he is a great example of the type of person I want to be when I grow up because he just keeps it real. He doesn’t really get into the celebrity trickery that has been afforded to him. People don’t really realize that Boy George came from this punk world and was actually a contributor to the scene. I was looking forward to positing him amongst his peers because George is still out therewith people like Princess Julia. He was working with Judy Blame before she passed away. There aren’t echelons of fame in this group. They’re all on the same level.

I interviewed Boy George for NOW magazine in Toronto when Culture Club was here and we got along really well. He was wearing some Leigh Bowery stuff and some Judy Blame stuff at the show when I met him. I know it’s a cliché, but we got along like a house on fire. It was the most fun ever. People wanted Boy George and Culture Club in the movie to make it more saleable, but I wanted to pan the camera away from the more heavily mined histories.

POV: The film includes a similar dynamic by looking at the work of Derek Jarman and then John Maybury, who gets to speak here. What influence have filmmakers like them had on you?

KH: I have spent time with experimental film and video as a programmer and as personal interest. Derek Jarman is like the Boy George of experimental film in that he’s always treated as this untouchable gay God figure. When I was speaking with people, his name was just “Derek.” It was, “Oh, Derek was there and Derek did this and Derek was cruising in the park.” It’s surreal when you start talking to these people. I really respect elder voices, cultural voices, subcultural voices.

I don’t really see a line between age and being interesting, or fading away. It was interesting to have Derek Jarman revealed to me as a human, as a peer, as a friend. At times, I felt like I wasn’t worthy of having his work in the movie because he’s so famous and, of course, being a gay filmmaker and having a past in the experimental art scene made it massively important for me to include him. I wanted to show how, in an arts community, your fore-people create a foundation for your work. Derek taking in John Maybury and influencing his practice reminds me of people like Bruce LaBruce, who’s a friend and has inspired me. He’s very generous and nurturing with other people’s work.

POV: What did making this film teach you about the mindset of aging?

KH: I thought it was important to show how directly the legacies were distributed to the following generations. There’s a tender narrative towards the end of the film about supporting youth culture. I didn’t want anyone to say, “There weren’t cell phones” or “This was before the internet.” That’s one of my biggest pet peeves. It was important to say that the kids make life cool. I think Derek Jarman celebrated that and everyone else in the film had that perspective.

I was really asking these people where this resilience comes from. What’s the secret? How do you stay interested? Sometimes my interest in things wanes, and there’s the saying that if you’re not interested, you’re not interesting. I was trying to glean whatever insight they had into staying so cool.

POV: One thing that really shines through the film is the way people stayed cool. Even though the figures in the New Romantics are of a different generation, they still have a great sense of style and seem very with it.

KH: They say Julia has been out every night for the past 40 years. She’s at every fashion show. She’s at every art show. I don’t know how many body doubles she has, but she has more energy than I ever have had. I had an ex and other people in my life who said I should start dressing my age. But I’m like, “This is my age.” I’m wearing a Björk New York t-shirt because I grew up with it. Just because everyone wears beige all the time, even though I know beige is popular these days, doesn’t mean you have to. That really bothered me. Why are you supposed to get boring as you get old?

As far as I’m concerned, you should get weirder and cooler with the more you’ve seen. It’s our responsibility to distribute that weirdness to people and cultivate that. When I was in London with my first movie, Jeffrey [Hinton] and Julia were DJ-ing every night when I went to the cool gay alternative bars, like Dalston Superstore or Vogue Fabrics. Age was not part of the conversation and I was drawn to how present people from that era were. I hope that people feel like they’re watching a movie about youth culture even though the people are from an older generation.

POV: The soundtrack and the editing let you feed off their energy. What inspired that style?

KH: The soundtrack is done by Verity Susman and Matthew Sims, who are incredible artists whose bands I’m a huge fan of. I wanted the music to avoid mimicking the “Eighties’ sounds.”People always say “an Eighties’ sound” or “an Eighties’ look” or whatever, but so many things were happening at the same time. Donna Summer was at number one when the Buzzcocks were playing. It was all happening at once. I also wanted to bring the contemporary in because, when you’re making this kind of movie, everyone’s like, “nostalgia, nostalgia, nostalgia,” and you’re trying to do something new with the narrative. I thought that that would be a good opportunity to have the soundtrack exist as a piece of art on its own. It’s relentless; it’s incessant.

I wanted everything to be a really fabulous punch in the face. – Kevin Hegge

POV: What was the process of finding a scrappy rhythm that mirrored the punk aesthetic of the New Romantics and the era?

KH: I just said, “Go wild” to everybody from Neil [Cavalier], my editor, to the composers. I was like, “No chill.” I didn’t want any chill anywhere. I didn’t want the titles to be chill. I didn’t want the music to be chill—I wanted everything to be a really fabulous punch in the face. That could bring it into the contemporary conversation because they [Verity Susman and Matthew Sims] both work with electronic music and they’re forward-thinking artists. Matt has a million bands and he plays in Wire, which is known for this type of art-punk music.

I didn’t want it to feel like a train of stock footage. If someone was talking about London being gray, we’d show a goth-y image—you don’t have to show a gray sky. You don’t have to show this cliché, so we were finding opportunities to challenge those instincts and make it more like a gallery of the work that was produced. You can see all these people collaborating and friends helping each other, and being absorbed into these iconic artworks and other ones that haven’t yet been exhibited in institutional spaces.

POV: Did you live in London prior to making this film?

KH: No, but since I was young, all my favourite bands, filmmakers, and art and culture were mostly UK-based. I’m rarely into American stuff. When I was invited to London for my first movie [She Said Boom: The Story of Fifth Column], I was over the moon. I got the newspaper of the day and took a picture of it. I went to every Morrissey lyric-related thing I could possibly find. The city was exactly how I dreamt it to be and being there just really suited me.

POV: Were you in any sort of scene growing up? Does Canada even have scenes?

KH: None that I can think of. There was a big punk scene in Canada on the west coast, and then Toronto Hardcore is a big community. Pomp and circumstance is a very English tradition. Dressing up and showing off is a very English thing, and Canada, not so much. There are Canadian artists who are more singular and have had huge influences on me. Peaches is one of a kind. I think that Canada has iconic people who stand alone, like Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones. Those icons resonate with me, but I don’t know if they’re particularly linked to a scene. What makes them so exciting is that they’re incomparable.

POV: One powerful part of the film is the sequence about the AIDS crisis and the film pauses with a montage of different figures who died and are the overlooked ones, so to speak. What inspired that interlude?

KH: That part was a continuation of trying to make everything democratic and valuing people who are just in the club as contributors to a community. They didn’t need to have some sort of art practice that screamed, “This is what I do to matter.” When I was interviewing people, it was striking how present the AIDS crisis was and the loss of their friends was—it wasn’t a faraway thing like it was for my generation or younger generations. I invited everyone to send me names of people who were performers and contributors to a certain extent. Every name was included.

It’s not even that these people were overlooked. Maybe they had no intention of being famous. Maybe they just wanted to cut hair. But that’s still creative energy that matters. These people’s names come up a lot, so I was familiar with them. Putting the faces to the stories was really heavy.

POV: It’s interesting to see a portrait of the club scene after two years of COVID when clubs have been closed and people haven’t really been able to gather in the way we used to. Do you think the club scene will come back?

KH: I feel like everything’s changing and that’s okay. Maybe we need to move on from clubs. They are important for creative communities and a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community—that’s integral to the sanctity of the community. The movie got more optimistic as we were working on it—we edited the whole thing over Zoom during the pandemic. A lot of the DJs I know have had to reimagine what sounds they want to play, how they want to present them, and the spaces in which they do that, be it in parks or whatever. I think it’s actually reinvigorating the way that we think about community. When we think about celebrations and spreading this energy, we’re used to doing in bars but maybe something more interesting will happen as we reimagine that. There’s this party called New Nails, which is my favourite. It has an earnestness and a sense of positivity that people are ready for, myself included.

POV: What about eras to go back to? Whenever I see a film like Tramps!, I find myself doing the Midnight in Paris thing and wondering about what time it would be fun to visit.

KH: People are starting to ask me about clubs that I hung out in and which artists I hung out with. Will Munro has a huge following in Toronto and should be an international superstar, but I was lucky to come to Toronto when that whole scene was thriving. That nurtured my perspectives. But if people talk about The Beaver, which is an institution in Toronto for us arty types and nightlife types, there’s nothing really interesting about The Beaver itself. That was my approach in the movie with the Blitz Club: I didn’t want it to be a “Blitz movie” or “Blitz Kids movie.” A diversity of art practices and personalities make up that community. That’s actually the individualism of that time. Would I want anybody asking me about some bar I went to for a week 20 years ago? It was just a bar.

Many times in my life I have been like, “I was born in the wrong era.” But I’m starting to see how nothing really changes—of course, modernity and technology change. The people and the diversity of interests make any era cool. I would say London in the Eighties, but it also totally sucked there. This movie shows fun, cool stuff, but it was a hard, bleak time for everybody.

POV: I doubt many people are nostalgic for the Margaret Thatcher days.

KH: Who wants to talk about her? There was the California punk scene, which was all artists, and women, and People of Colour, and queers. That was really hardcore, which is crazy because so much was happening at the time with pop culture. It was an underbelly thing. It wasn’t rich kids in New York—and there was the beach. I think that that would be my ideal place, but otherwise just lots of London, lots of London. How about you?

POV: I don’t know. I think on one hand I’d rather just live now without the COVID. Even if we feel like there’s a boring art scene, I think I’d rather live in a time where things can be open and legal. Although I’m excited by the trend of speakeasies that seems to be happening and should get me out of the house.

KH: I do feel like Toronto as a film city and as an art city is changing. The Queer West art scene that I was referring to before was a hugely important element of my social life and for developing my perspectives on things. It’s not even the clubs that I miss so much. It’s more like the art scene. In that world [the New Romantics year] the floors ended up moist no matter what. I miss that energy in Toronto and I don’t know if it’s dissipated in other cities. I think it’s still 24/7 in London, but I would like that element to be back in whatever guise.

POV: And the film speaks to what we’re seeing here today: a sort of exodus of the art scene.

KH: The movie gets the idea of cities becoming unlivable and pushing out artists. The artists make the city cool in the first place. If you push all the artists out, it’s gonna be a bunch of bankers—not that there’s anything wrong with being a banker—but capitalism is shooting itself in the foot. Or the face. It’s completely obliterating any opportunity for young art makers to a creative output. Young people are still doing cool stuff in Toronto. I think that things are just going back underground, which is great.

Tramps! screens as the Centrepiece at Toronto’s Inside Out LGBT Film Festival on Tuesday, May 31 at TIFF Bell Lightbox and will be released later this year.

Update: It screens at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on June 22, 2023.