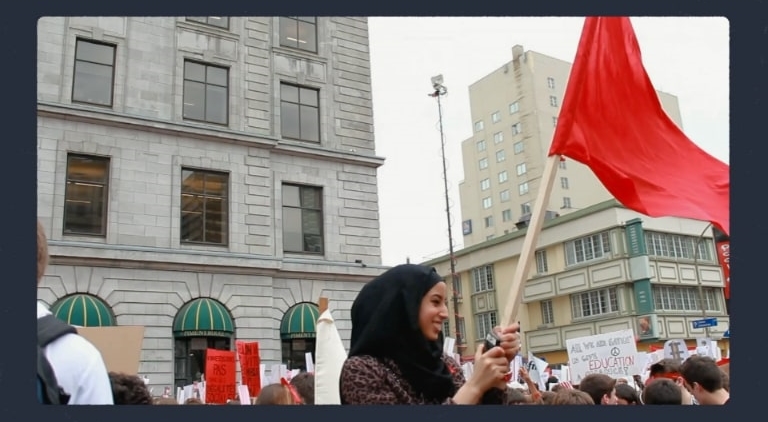

Those who follow Quebec politics have noticed an unmistakable phenomenon: the sovereigntist movement, once proudly progressive, has taken a sharp turn to the right. The Parti Québécois, the separatist party which has formed several governments since 1976, has championed legislation that sought to protect and promote the French language in Quebec; they also brought in the first gay rights legislation in North America, and ushered in universal subsidized daycare. But more recently, the right wing Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) is running the province with a clear majority. They have voted a series of controversial bills into law, including Bill 21, which prohibits anyone wearing a religious symbol (turban, kippah or hijab) from working in the public service and used the contentious Notwithstanding Clause to sidestep the scrutiny of the courts.

This sharp turn is explored by legendary Quebec journalist Francine Pelletier in her new documentary, Bataille pour l’âme du Québec (The Battle for Québec’s Soul), which airs this week on Ici Télé. In the film, the seasoned journalist speaks to a number of authors and academics about the seismic shift in the sovereignist movement—the reasons for it and possible alternate futures for Québec society. Pelletier sat down to talk about her new controversial documentary with POV Magazine in an Outremont cafe.

FP: Francine Pelletier

FP: Francine Pelletier

POV: Matthew Hays

POV: What led you to this idea for a documentary?

FP: I was approached by Radio-Canada almost five years ago, shortly after the infamous Unite the Right demonstration in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. Suddenly there was a need to see if this kind of blatant racism and xenophobia was burgeoning elsewhere, including in Quebec. As scary as the Far Right can be, after some initial research, it was obvious that neo-Nazism is extremely marginal in Quebec. A far more egregious problem, it seemed to me, was how nationalism in Quebec has slowly transformed itself from a progressive movement to a regressive one.

POV: When did you get the sense that there was a huge shift in Quebec society?

FP: In the wake of 9/11 but especially following the Supreme Court ruling on the kirpan, Quebec has been shaken by what was called “la crise des accommodements raisonnables.” In the fall of 2006, Mario Dumont, the leader of a small right of centre political party, set the stage by summoning Quebeckers to “put their pants on” and stop being so “accommodating” toward religious minorities. There are many other events that explain why nationalism became more “identity” focused, but this crisis in 2006-2007 marks the true turning point.

POV: What was the biggest surprise for you when researching this film?

FP: I had underestimated how much losing two referendums, and especially the last one in 1995, psychologically wounded Quebeckers. I think this is something that is very much misunderstood in the rest of Canada, by the way. The dream of independence also meant that francophone Quebeckers could feel strong, less vulnerable in terms of their cultural future. People start hunkering down and building walls when they don’t know what’s going to happen next. That’s precisely what started to happen shortly after the last referendum. The film walks you through each of these transforming moments in Quebec’s recent history.

POV: What was the toughest part of making this movie?

FP: Getting the door shut in my face by many of the very people at the heart of this political transformation—people like Mathieu Bock Côté, Jean-François Lisée and others—who not only refused to be interviewed for the film but also maintain that I am making this up. They argue that Quebec is essentially the same place it’s been for the last 40 years. It isn’t. The film demonstrates it, I think, quite eloquently. For sure, the film is controversial. I will have to bear the brunt of that. However, I’m hoping that Bataille pour l’âme du Québec (The Battle for Quebec’s Soul) will show that, though the conservative voices have swayed the debate to their advantage, the progressive voices are alive and, if not well, very much still kicking.

POV: You couldn’t have known about Bill 96 when you first started this project. What do you think of this legislation? [Bill 96, voted into law shortly after press time, is the new sweeping language legislation that will impact legal, medical and education services drastically in Quebec.]

POV: You couldn’t have known about Bill 96 when you first started this project. What do you think of this legislation? [Bill 96, voted into law shortly after press time, is the new sweeping language legislation that will impact legal, medical and education services drastically in Quebec.]

FP: It is normal for Quebec to legislate around language. For the longest time, three things “preserved” Quebec identity and therefore its future: the Church, close-knit rural communities and the French language. Today, French is the only thing maintaining Quebec’s distinctiveness. So of course it has to be protected. That being said, Bill 96 is like too much of the legislation favoured by the Legault government. Like Bill 21 on religious signs, its real purpose is not so much to solve a problem as to pretend that the government is looking after its own, i.e., the “historical francophone majority.” It’s identity politics, done with an eye on the upcoming election, and with little to no regard for the cultural minorities this legislation affects.

POV: You’re dealing with a lot of very complicated questions in this film, about identity and history. You manage to pack a lot into an hour, but was that difficult? I felt like this could have been a miniseries.

FP: You’re right, it is a complicated question involving a fair chunk of history and a mere 52 minutes (the pre-ordained length of TV documentaries) doesn’t quite cut it. I’ve submitted a podcast series proposal to Radio-Canada for that very reason: to allow us to explore the question of nationalism, and use all the great interviews we’ve gathered in the process, to its fullest. But whatever the format, the difficulty we are facing still remains. We are talking about something that hasn’t really been broached before. As far as I know, this is the first real exploration of Quebec nationalism over the last decades. It’s much easier to look at something that has long been established than something that is still evolving. The fact that not everyone agrees with this transformation of Quebec’s identity—starting with some of the very people who are behind the conservative turn of events—makes the subject all that more difficult to grasp.

POV: What do you think René Lévesque would say about where Québec society is today?

FP: It’s hard to speak for the dead. Especially since many Parti Québécois stalwarts are today in favour of this back to the future kind of nationalism, a conservative immigrant-shy mentality that smacks of times gone by. I like to think, however, that René Lévesque, like many of us on the Left, would be dismayed by this turn of events. There is a wonderful excerpt of him in the film, from the early days, explaining what his sovereignty movement is about: “This is not about being against people who are different from us,” he says. “We have an opportunity here, that of building a model society.” I would like to think that this “model society” can still be built.

Bataille pour l’âme du Québec (The Battle for Quebec’s Soul) streams online and airs this Saturday, May 28 at 10:30pm on Ici Télé.