Much of Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland simply observes actress Frances McDormand as Fern, a woman travelling the USA in search of seasonal work, in conversation with fellow nomads. These mobile-home-dwelling workers, or “workampers” as they call themselves, are not professional actors like McDormand. They’re genuine workampers enacting the drama of their lives. Their stories inform the book Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century by Jessica Bruder, on which Zhao bases her film. Workampers like Linda May and Charlotte Swankie tell their stories in Nomadland once again, but this time to McDormand. The two-time Oscar winning actress delivers a masterfully understated performance as she listens to their words with respectful attentiveness. These stories come from the heart and they speak of a nation in crisis.

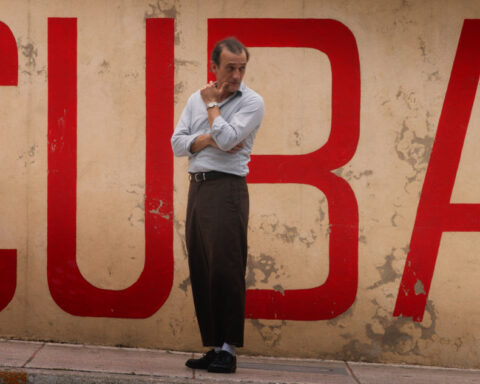

Fern herself hails from the town of Empire, Nevada, which became so destitute following the closure of a sheetrock plant in 2011 that the postal service disbanded the local zip code due to the exodus of residents. Fern knows hardship and the pain of hitting rock bottom, having lost her home shortly after the death of her husband.

Fern, however, does not see herself as homeless. Stealing a line from Linda May, who is the chief subject of Bruder’s book, Fern calls herself “houseless.” The difference, the workampers convey, is one of agency and security. Fern doesn’t want handouts and neither do any of the fellow travellers who get by precisely because they all arrived at a crucial decision. While a home provides a person with a foundation and security, it’s also the single largest expense one can carry. Hence the distinction between house and home. A trailer, van, or hatchback car can be a home with the right perspective.

Rolling around the heartland of America, captured with picturesque beauty by cinematographer Joshua James Richards, Fern joins the “parade of Christmas lights” that employers recognize as the caravan of workampers moving with the seasons in pursuit of itinerant work. Fern enjoys a gig at Amazon during the Christmas rush. She supervises a camp during the summer. She harvests beets in the cold of winter. These jobs pay relatively little, but they’re enough to help a person get by while providing daily purpose. Her old but steady van Vanguard is what she needs. With each location, Zhao observes the nuances of the workampers’ reality, capturing the communities they form and the hardships they face while adapting to survive with the changing seasons.

Zhao’s adaptation of Bruder’s book is relatively loose, but tackles the subject with equally dextrous care. Where Bruder’s work makes an intellectual argument, Zhao’s film makes an emotional one. It’s doubly compelling because one feels with greater weight the fallacy of the American dream when face to face with the personas who inform Bruder’s book. The film only has one professional actor in a role of any prominence alongside McDormand: David Strathairn as David, a fellow nomad whose travels intersect with Fern’s journey, igniting sparks with each collision. Strathairn, like McDormand, has a weathered an unassuming presence that suits Zhao’s aesthetic perfectly well, capturing with quietly restrained dignity his character’s desire to reclaim the comfortable life he once had.

Fern ultimately offers a stand-in for Bruder, rather than a composite of characters like adaptations often favour. The book sees Bruder travel much of America as Linda May’s sidekick, researching the workamper lifestyle while experiencing it firsthand. Fern, on the other hand, traverses the land independently, crosses paths with Linda May infrequently depending on where the work takes them. Linda May invites audiences into the Squeeze Inn (her van) and teaches Fern tricks of the trade as she adapts to a lifestyle that, for her, is relatively new. Linda May clearly has experience showing new nomads the ropes, so the role is a comfortable fit for this lively personality.

The other face from Bruder’s book that figures prominently in Zhao’s film is Swankie, a veteran workamper with magnetic screen presence. Swankie rivals McDormand in perhaps the film’s finest moment as she tells Fern about her cancer diagnosis and reflects on the time she has left. When a person confronts her mortality on screen and coughs, leaving traces of blood on her chin following the involuntary motion, a film operates with visceral gut-level emotion. Few actors can replicate this gravity and McDormand reflects it effortlessly. Very often, McDormand says nothing because few words can console a person when she or he is confronted with the loss of a dream.

Great acting is often about reacting and the reaction shots of Frances McDormand are the secret ingredient to Nomadland. The film furthers Zhao’s unique style demonstrated in her earlier features Songs My Brother Taught Me and The Rider. Those films, like Nomadland, cast everyday Americans as dramatic extensions of themselves. This approach brings both risks and rewards, since non-professional actors are inevitably more limited in their dramatic ranges. Like Linda May and Swankie, the characters in Zhao’s earlier films generally excel when telling their stories or tracing familiar terrain before the camera. Brady Jandreau, for example, carries The Rider with effortlessly quiet grace. However, when an actor of McDormand’s calibre can react to the authentic, pure, and raw emotion of the confessionals laid bare by the workampers, the hybrid effect draws the best from both worlds.

Nomadland achieves a new kind of poetic realism for American independent cinema. It honours the true salt of the earth people who inspire it, but ultimately elevates their tale through McDormand’s heartfelt and empathetic performance. Nomadland is a snapshot of contemporary America where the American dream is in tatters, but hope for a better alternative nevertheless resides.

Nomadland premiered at TIFF opens In theatres April 9 and is streaming on Disney+.

Read more about the hybridity of Nomadland in Acting Naturally.

This review originally ran during the 2020 Toronto International Film Festival.

Visit the POV TIFF Hub for more coverage from this year’s festival.