MLK/FBI

(USA,104 min.)

Dir. Sam Pollard

Programme: TIFF Docs

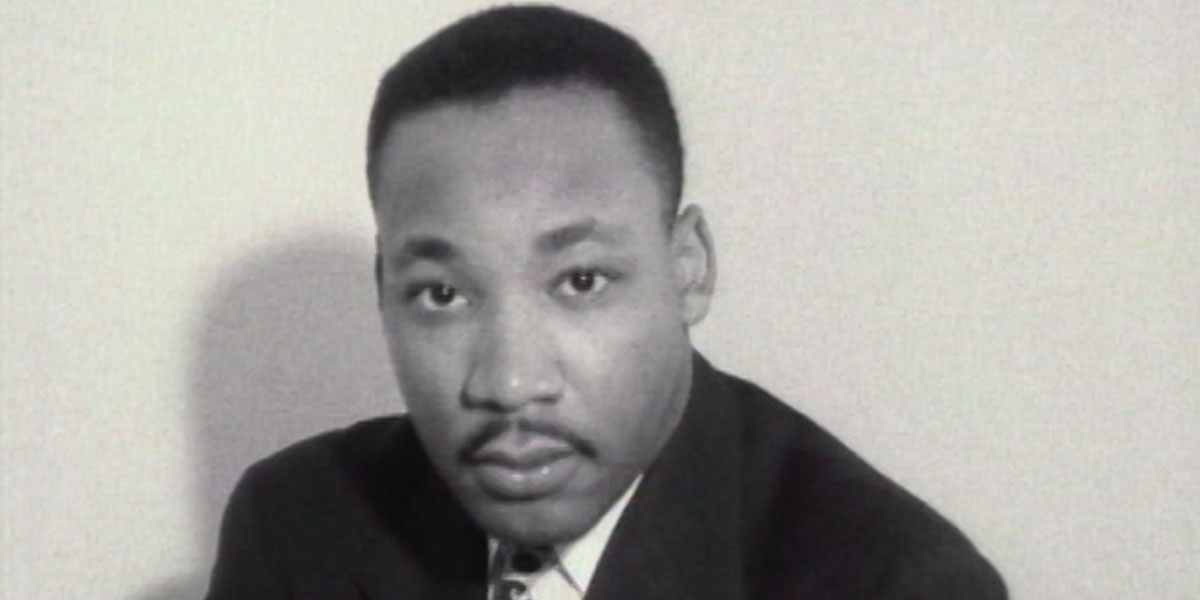

The hatred that J. Edgar Hoover, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) felt towards Martin Luther King (MLK) was one of the key hot spots in the bitterly confrontational Sixties, when an unrelenting series of demonstrations by the Civil Rights movement, led by King, overturned racist segregationist laws in the United States. Hoover, who was used to being considered an American hero and whose FBI had stood up against mobsters and Communists, couldn’t abide being confronted by the young articulate Black minister whose bravery against Southern racist police and stirring rhetori, made him a Nobel Peace Prize winner, when he was barely in his thirties. Through wire taps and paid informants, his FBI contrived to make MLK’s life as miserable as possible while King was working towards a greater understanding between not only races but classes in a very divisive America.

Veteran filmmaker Sam Pollard, whose credits as editor, and increasingly director, include the Civil Rights classic series Eyes on the Prize, Spike Lee’s Four Little Girls , Two Trains Runnin’, a Sammy Davis, Jr. doc and Why We Hate, proves himself to be the right man to tell the story of this contentious relationship, which was so consequential in the Sixties. Through judicial use of archival material, Pollard is able to show the popularity of the FBI during the period with scenes from The FBI Story (starring Jimmy Stewart) and the TV series The FBI. MLK comes off just as well as we see him winning the Nobel Prize in Sweden and stirring millions with his presence at the 1963 culmination of the March to Washington when D.C.’s entire mall was covered with protestors drinking in King’s promise of greater racial equality.

Pollard is forced to deal with the fact that King was hardly a monogamous man, which greatly enraged Hoover and many of his minions at the FBI. At the lowest point in their relationship, the FBI penned a note to MLK revealing what they knew about him in the hope that he would commit suicide. If the FBI knew anything about the fatal assassination of MLK or previous attempts, they clearly didn’t reveal anything to him. And yet, they caught his supposed killer surprisingly quickly and acted with total professionalism—after he was dead.

King and Hoover are long gone now. So are the Sixties. But Pollard’s lucidly intelligent film shows what happened then: a fatal situation in which a Black man confronted the white establishment. It doesn’t take a stretch to point out that Pollard’s film has relevance today. MLK/FBI is a strong, quietly artful film that deserves respect—and to be viewed by a large audience.