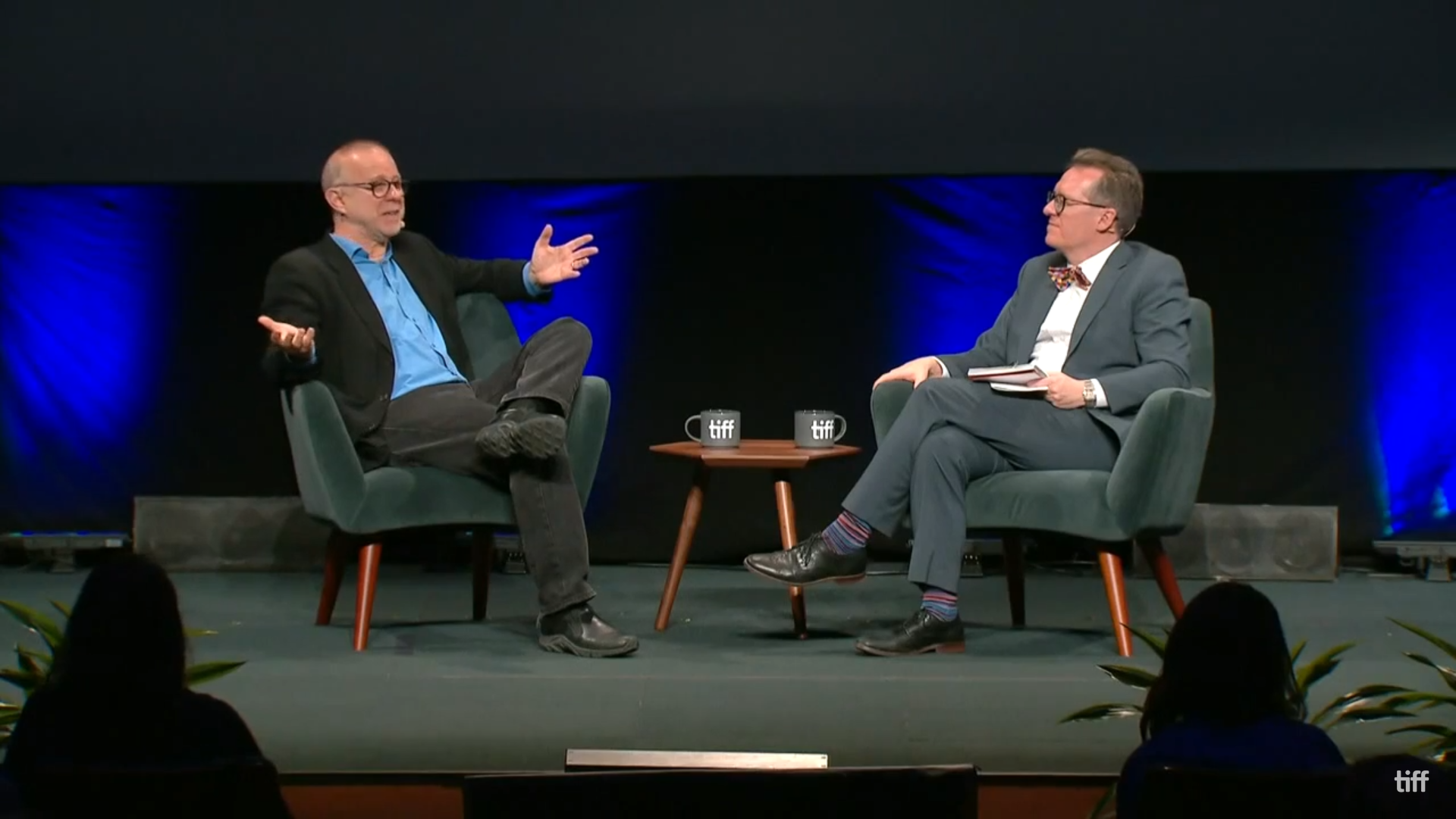

In the opening session of the TIFF 2019 Documentary Conference, Alan Berliner said that he didn’t mind being called a documentary filmmaker. Relaxed and genial onstage at the CBC’s Glenn Gould Studio, the maverick even among other mavericks told the event’s creator Thom Powers, “That’s the church that will have me. It’s certainly the community that I travel in. I’m a card-carrying member.”

Berliner went on to talk about his idiosyncratic ideas and approaches to documentary. “Every film that I make,” he said, “is kind of a leap of faith.” Movies like Wide Awake, an exploration of Berliner’s insomnia, and The Sweetest Sound transport viewers into his obsessions and preoccupations. In The Sweetest Sound, he wonders about the mysterious powers that names may have and seeks out people who share his.

Delving into his origin story as an artist, Berliner recalled his first job as an ABC Sports sound effects librarian. The work sensitized him to the impact of sound, which his films use forcefully, and triggered his obsessive archiving. Berliner chatted happily about his massive collecting. His archive, everything in it neatly filed and identified, includes thousands of photos and innumerable reels of sound effects. He has collected “800 images of floods and displaced people. I have trouble throwing things away.” Every day, Berliner snips out New York Times images that grab him. Pictures in his Times collection are the raw materials for Letter to the Editor, his first movie to screen at TIFF.

Berliner harbours various images of himself. He compares himself to his tailor grandfather weaving material together. He’s also a collagist, inter-connecting found pictures and sounds. Berliner admits to being OCD (obsessive compulsive), but does not consider himself a hoarder, nor does he seek stuff for its monetary value.

“I have ten boxes of Life magazines that stare at me every day,” Berliner smiles. “I don’t know if I will ever get to them, but they represent a potential for another deep dive into another kind of an ocean. Everything that I save, that I catalogue, is for potential new combinations, which is another way of saying new ways of looking.”

While Berliner finds plenty to admire in digital media, his new film, Letter to the Editor expresses his love of print. ”The smell, the touch of newsprint, the sound of turning pages,” he says wistfully, “that’s hard to express. I am connected to it. With the Internet, I go to the world; with a newspaper, the world comes to me. I’m holding something that’s been curated and composed in a way that makes me feel grounded, a kind of briefing.”

Online, “news sources are continually refreshing themselves as a stream of consciousness in real-time.” What happened on a particular date? “Was that at eight in the morning or eight at night. We’re going to lose another measure of history, a way of understanding the world.”

Hard-Coded

Following Alan Berliner’s somewhat whimsical opening session, Elise McCave, the business-like director of Narrative Film at Kickstarter, gave a rapid-fire update on her company. Far more than just a fund-raising tool, Kickstarter has a mission: to bring creative works to life, while, according to McCave, encouraging a positive image of society. At the end of her presentation, she offered tips on how to best use the platform.

McCave pointed out success stories like the five Kickstarter funded projects that screened at Sundance 2019. The highest profile title, Knock Down the House, which tracked the congressional primary campaigns of four progressive women, notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, raised $25-$30,000 on the website before selling to Netflix for $10 million. The more recent God Said Give Em Drum Machines tells the story of the unheralded black involvement in the creation of Detroit techno music. McCave added that fifteen Kickstarter films have been nominated for Oscars.

Moreover, the exec explained proudly, Kickstarter has become a PBC, or Public Benefit Corporation. “It’s a relatively new corporate structure, and it means that we are obligated to consider the implications of our decisions on society,” McCave explained. “Benefit to society is hard–coded into our legally defined goals.”

Kickstarter supports organizations that encourage equality, helps mentor burgeoning young filmmakers of color, and provides free childcare to people screening their work at certain festivals.

According to McCave, the average amount the platform brings to a venture is $20,000 for a documentary, less for fiction. She advises creators to “figure out who your audience is and go for the kill there.” The Legend of Machin, an animation project based on a game with a big following, picked up millions of dollars in a day.

Avoid bad times for launching a campaign, McCave advised. Vacation periods are a no-no because “most people are still pledging on computer, rather than their mobiles.” Interestingly, Tuesday, early afternoon, enjoys the “highest success for projects while the lowest is Sunday morning.

Old School News

The Conference’s third session united doc-maker Yung Chang (Up the Yangtze, China Heavyweight) and journalist/author Robert Fisk, the subject of his new doc, This Is Not a Movie. Co-produced by the National Film Board (NFB), the film depicts Fisk’s long career covering the Middle East by flipping back-and-forth between past and present. In archival footage, he’s a young Michael Caine lookalike banging away on a typewriter. Cut to Fisk hammering the keyboard of a MacBook Pro. In conversation with Thom Powers, the duo delved into Fisk’s work methods and ideology while talking about ideas spinning around This Is Not a Movie.

Chang recalled that the NFB approached him to direct, even though he had never been to the Middle East. Fisk thought working with someone ”unfamiliar with the region” would be interesting. “You’re quite fun to be around,” the filmmaker told the reporter. “I thought we could spend a couple of years together making the movie.”

This Is Not a Movie portrays an old-school journalist who is leery of the multiple information sources and uncontextualized data in the Internet Age. In a core sequence, we watch him track a story from an Al Qaeda basement to Bosnia to Saudi Arabia, questioning key figures face-to-face, scribbling quotes in shorthand. Fisk met up with Osama bin Laden more than once and delights talking about the interview when his pen ran out of ink, and he borrowed a pen from “an Al Qaeda thug.”

Naturally, both Fisk and Jung have concerns about the new media landscape. Confusing the facts with “fake news is an invention of the White House,” says Fisk, and too many journalists kowtow to dangerous demagogues. “There has become a new version of news, but you must do your job, while these curtains are billowing over everything.”

For Fisk, doing your job means keeping your cool. It’s not to “weep for the dead; it’s to tell you about them. I don’t have nightmares. I can go out for dinner after seeing something terrible.”

Fisk recalls a reporter, who, devastated by the horrors he witnessed, committed suicide. “And he was a very strong character. I think that if a journalist feels that he can’t take it anymore, he should leave. Don’t think there’s something manly about staying on board.”

Sign of the Times

Alan Berliner obsessively scissors images out of the New York Times. Robert Fisk, who writes for The Independent no doubt wishes his outlet had not gone 100% digital.

In her presentation at the Conference, Kathleen Lingo described how the 170-year-old NYTimes (NYT) has not only gone beyond print, it’s morphing into a production company. Lingo is the NYT’s editorial director for film and television, responsible for shepherding movies and television series. The new direction evolved from the ongoing short documentary series, Op-Docs.

Lingo explained how Op-Docs have been assembled by filmmakers who extrapolate from a feature they made, or want to push an idea into a movie. “The first Op-Doc we ever published,” says Lingo, “was Silent Majority by Penny Lane and Brian L. Frye,” a short derived from the feature Our Nixon.” The 313 and counting Op Docs, which include films by Errol Morris, tend to favour cinematic experimentation and characters that pop out at you. A man is fascinated by his late father’s porn tapes, a holocaust survivor in her 90s joins a metal band, a Greek Coast Guard officer who, says Lingo, “was literally pulling hundreds of refugees out of the water every day.”

Lingo explained to filmmakers in the house, “There are many flavours in the shorts to features pipeline. It doesn’t always work to do a short from a feature. Sometimes, we talk to filmmakers who have made features, and who want to do a short.” Producers and directors working with The Times pick up on resources like millions of photos going back 150 years, not to mention wide access in many countries. Then there are the 41-million Twitter followers, a huge potential for marketing a film.

What’s the motivation for the venerable newspaper? “We’re reaching new audiences,” says Lingo. “If we want to continue what we’ve been doing for another 170 years, we need to meet audiences where they are. We are reaching out to the audience where it is: screening platforms, in the theater, on a screen of any size.” The Times is also producing fiction, not just documentary, “which can get at truth, our core mission.”

Pushing the Canoe

Kathleen Lingo of The New York Times segued to Heidi Tao Yang (of Hot Docs), Claire Aguilar (the International Documentary Association), and Jesse Wente (the recently launched Indigenous Screen Office ) discussing problems that arise when Indigenous people and moviemaking come together. All three work toward solving complex problems and finding ways to get Indigenous stories onscreen.

The Indigenous Screen Office (ISO), Wente explained, must operate in Canada, “on this side of the colonial border. Because we are largely publicly financed, they tend to want you to use the funds in the area the colonial government dictates.” For Ojibwe Wente, “the border is not our border. I’m not sure it makes sense for Indigenous artists to have to follow its rules.” Perhaps one day, the long-time writer and broadcaster hopes, the anomaly will be corrected, and the ISO will be free to disperse the funds it receives wherever it wants to.

Wang, Aguilar, and Wente discussed a recurrent and pervasive issue, non-Indigenous filmmakers who depict Indigenous subjects. They all agreed that such filmmakers must do so with caution and sensitivity. “You need to understand the right way to go into a community,” Wente says, aware of “the reciprocal nature of that relationship. You must know how you should leave more than you take out, and how you should be considered the right person to tell an Indigenous story” if you are looking in from the outside. Moreover, “is there an Indigenous person who might be better suited to tell that story?” Then of course, there is also the thorny issue of who owns the rights to any given narrative.

Despite all the problems, setbacks, and long history of invisibility in the media, Wente is cautiously optimistic about the future. One of the ISO’s early accomplishments was signing a favourable deal with Netflix Canada.

Wente thinks there will be gradual, “incremental changes. Ideally it should not be news to see Indigenous people in the media. Over the next five years, we can push the canoe into the water.”

Problematic

The next session, on trends in documentary curation, pointed toward some hard facts about film festivals. Whatever an event’s idealistic mission statement, festivals “are not egalitarian,” said programmer Abby Sun. Experienced filmmakers pay less for submissions, and the big stars sometimes receive fees without even knowing how their work was submitted.

Sun, Ashley Clark, (senior programmer at the Brooklyn Academy of Music), and TIFF Conference programmer Denae Peters discussed how festivals should contextualize submissions, stand behind filmmakers, and never leave them alone at a mic stand. But what about films that for one reason or another are problematic? Drawing attention to flaws, contextualizing, and counter–programming are strategies that don’t necessarily work. People “don’t necessarily stay for Q&A’s,” said Abby Sun.

Case in point, Dominic Gagnon’s notorious of the North, an assemblage of YouTube clips that adds up to a picture of Inuit people living in violent, drunken misery. Gagnon defends the project as a critique of “the idea of representation, so buzzy right now in the industry,” Sun pointed out. The Montreal International Documentary Festival (RIDM) “showed it and was heavily criticized.” Among other objections, Gagnon used music by singer Tanya Tagaq without permission.

Sun was not impressed by RIDM’s strategy to defuse the uproar: a series of panel discussions about Indigenous filmmaking. Eventually, Gagnon did have to pull his appropriated clips from YouTube, and his project narrowed down to 74 minutes of black.

For Sun and Ashley Clark, repeated screenings of delicate or difficult movies are an effective way to handle them.

”There is an amazing short film called America by Garrett Bradley,” says Clark, which “is an impressionistic film that imagines what black life on film would have looked like were it not for the effects of something like Birth of a Nation. We screened the film on seven consecutive days, each day with a different complementary component around it.”

For example, the short played with Hale County, this Morning, this Evening, a meditation on contemporary Black life. Not only do the two movies dovetail thematically, both use footage from the 1913 comedy, Lime Kiln Club Field Day, one of the first films with a Black cast.*

The Brand

With a friend and colleague, I once pitched a project at Showtime. The pitch was a good experience that confirms the advice Vinnie Malhotra, Showtime’s Executive Vice-President of Non-Fiction Programming, offered to filmmakers at the Conference. I never would have got past the gatekeepers without my friend, who had a long history with the network.

“I can’t sit here and say send a project, and we’ll take a look at it,” said Malhotra. ”The cold call never really works with a place like us. I do think documentary is a very tight community. When you look at your network of people, there are probably other filmmakers, programmers or producers who have a connection to somebody at Showtime or to me. I can honestly say that we are trying to find fresh and new perspectives of storytelling and new filmmakers. We do have our ears perked up for that.”

Documentary production at Showtime has been up-and-down, continued Malhotra. But CEO David Nevins is committed to non-fiction production. The tipping point for the industry were hit projects like The Jinx, which led to flurries of doc production. ”Documentary for the longest time has been for a documentary audience,” said the executive, “now it has become far more accessible.” Of course, the surge is at least partly due to what he calls a “crowd of true crime stories.”

Malhotra emphasized that Showtime brands itself as contemporary, not historical. Nevertheless the network can encompass many different kinds of projects, for example in music, Nick Broomfield and Rudi Dolezal’s Whitney: Can I Be Me? is one of the network’s high-profile productions. Screening at TIFF 2019, Lauren Greenfield’s The Kingmaker zeroes in on Imelda Marcos’s power plays in the Philippines while Andrew Renzi’s Ready for War is a sadly touching story about immigrant volunteers to the US military who “were all deported to Mexico.”

One of the doc’s three characters typifies the fate of deported veterans who get recruited by the drug cartels “all too happy to get a US trained soldier into their militia.” He “went over to the dark side” and become a Sicario for the Juarez cartel.

Talking about Ready for War, Malhotra gave insight into the decision-making process at Showtime. “I was excited by the fact that the story was relatively fresh and new to me. I was also very taken by a young filmmaker and the boldness with which he approached the story.” The film is powerfully disturbing, but it’s “not a full scale adrenaline rush, or delving into deep toxic masculinity.”

Malhotra bonded with the project after viewing a ten-minute reel. Within three minutes, “I was very aware that we were going to jump on board and make this project with him.” Once Showtime is on board, “It becomes an immediate collaboration. We are talking about what they’re shooting and coming back with, and we give notes. They had a very specific vision of how they wanted to tell the story. We were very supportive of that and went with it.”

Of course, Showtime partners frequently with veteran filmmakers like Alex Gibney and Liz Garbus, whose docu-series about the New York Times, The Fourth Estate, played the network. Doc-makers like Gibney and Garbus “have a strong sense of what they want to do,” says Malhotra. “We have an ongoing conversation, focusing on structural issues rather than time code notes.”

While Showtime looks “for projects that exemplify the brand, there are no hard and fast rules. You can do a film about an icon like Marlon Brando, a music film, or something that’s much more in the realm of current affairs. It’s really about how you tell those stories.” Overall, shows should be alluring and as compact as possible.

Cherish

The 2019 Doc Conference was bookended by Thom Powers’ conversations with two major filmmakers: Alan Berliner in the morning, Oscar winner Barbara Kopple in the late afternoon. During a lengthy conversation, Kopple revealed some of her methods and perspectives when she talked about her new film Desert One. The doc tells the sad story about a failed mission: the attempt to rescue American hostages in the aftermath of the Iranian revolution.

”I have done many films about the military,” Kopple told Powers. The first, Winter Soldier, “told the painful story of Vietnam veterans.” During production, Kopple lived communally with the vets. “I remember we would wake them up in the morning, and they’d still think they had their weapons.”

Kopple recalled that “when Desert One came along, it seemed like I got to go into a world of men, and I like going into a world of men. I find you very fascinating,” she grinned at Powers as the audience laughed. “It was something I wanted to explore. Here were these guys from Delta Force who are trained and who are tough and strong and keep everything inside. I really wanted to interview them and let the emotions come out.”

Although she found interview subjects, including President Jimmy Carter, whose political career was taken down by the hostage debacle, ”it was a secret mission, and there is no footage, not even a still photo. Nothing. So we had a wonderful Iranian animator” who rendered some of the action.

To interview a reluctant ex-president, Kopple relied on a string of contacts, particularly long-time Jimmy Carter supporter, Phil Wise. The president is not emotional, Kopple was told, but as they talked during a 20-minute interview, tears welled up in his eyes. Luck on her side, the doc-maker managed to find an “archival treasure chest” in Iran.

When asked about her approach to interviews, Kopple said she never does them cold. She creates a conversational relationship before she goes in. On the other hand, for one of her best films, Miss Sharon Jones!, about the titular late great r&b performer, Kopple “started filming on their first meeting.

“She had just found she had cancer, and she was having her hair shaved. That was the first time I ever laid eyes on her, in person, or ever met her. It linked me so much to her because it was so intimate, so personal and so private.”

Kopple had told Powers, she did not want to talk about her close connection to the brilliant, ground breaking filmmaker, D.A. Pennebaker. He had just died, and her feelings were raw.

But as the session wound down, she changed her mind and paid graceful tribute to a man who was an early supporter, mentor and friend. When she was making Harlan County, USA, the film that catapulted her into the doc stratosphere, “I felt nobody believed in me.” The reaction was ‘Why would a little girl like you want to do a film like this?’”

Pennebaker had a different reaction. After she showed a rough cut to him and other filmmakers, ”he was part of, in every way, helping me getting this film finished.” Reacting to a particular sequence, Pennebaker said to a group of film veterans, “If this woman can get this,” then he and his colleagues had to support Kopple in any way they could. “That started our friendship. He meant the world to me. I feel honoured to have had such a wonderful, supportive presence.”

Kopple has been around for a long time. Despite the fact that funding a project will probably always be a grind, “Once I jump into a film, I’ve never been happier. I’m totally lost in it and really want to get connected to the people. It’s almost like I have single vision. It’s something I just love and cherish.”