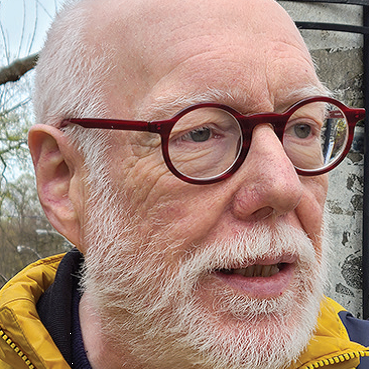

“Three hours after I landed, they told me that the premiere had been cancelled because of COVID,” says They Call Me Dr. Miami director Jean-Simon Chartier. “If the premiere would have been held the night before, I would have been able to show the film to the public.”

Chartier is one of many filmmakers exploring the strange reality of premiering a film when precautions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic make in-person festivals with audiences impossible. They Call Me Dr. Miami was scheduled to have its world premiere at the Miami Film Festival on March 12. However, after the event was cancelled mid-run mere hours before the film’s scheduled premiere, Chartier says he later watched the premiere on Instagram. Participating in the festival’s Q&A in his place was subject Michael Salzhauer, best known as Dr. Miami, a larger than life plastic surgeon/influencer breaking the stigma surrounding cosmetic surgery one viral video at a time.

Chartier is nevertheless pragmatic about the situation. “We need to put this in perspective,” says the director. “There are things that are much more serious than being able to have a film in front of an audience.” They Call Me Dr. Miami’s next stop on the virtual circuit is May 14 as part of the Hot Docs at Home series. It will also participate as an official selection in Hot Docs’ online festival beginning May 28. This time, Chartier won’t just be watching the premiere of his own movie on Instagram.

Miami Culture and Dr. Miami

However, viral videos in the era of coronavirus make They Call Me Dr. Miami ironically timely. Newsfeeds and social media sites are rife with Boomerangs, videos, selfies, and TikToks of twerking hotties and beer-gutted Floridians bronzing on the beach. The film is fascinating to watch as a window into the “Miami culture” that inspires waves of people to flock to the beach and display their bodies in the middle of a pandemic. Through its fun and balanced profile of Dr. Salzhauer, The Call Me Dr. Miami opens up a wider consideration of body image and self-promoting shamelessness.

The film reunites Chartier with Salzhauer after the doctor briefly appeared in the director’s Radio-Canada documentary Corps à la carte, a broader survey of the quest for eternal youth through plastic surgery. “The film had a few talking heads specialists speaking about the historical and psychological points of view,” explains Chartier. “It was more like an analysis of the phenomenon. Through the research, we encountered Dr. Miami – the most ‘famous plastic surgeon of the universe,’ as he would call himself. I spent less than a day with him at his clinic doing an interview and shooting inside the operating room.”

A few minutes with Dr. Miami are all one needs to see what makes him unique among his colleagues. The showy and verbose doctor harnesses the power of social media to celebrate the bodies he nips and tucks beautifully. Gangsta rap, bling, and booties fuel his videos, which evoke a pimped-out meat market in which women boast rejuvenated confidence through the enhancements of plastic surgery. His Instagram account boasts over 160,000 followers and his audience nets over 2 million likes on TikTok. With his booty-shaking staff and energetic patients, Dr. Miami’s social media channels make public a topic that remains relatively taboo even among its practitioners.

Dr. Miami at Home and at Work

Dr. Miami appears only for a few minutes in Corps à la carte, but Chartier says he instantly recognised a great character through the brief encounter. “I met someone who was bigger than nature, who was much more complex than what I was able to show in a three-minute segment,” reflects Chartier. The director says he put in a request for a full shoot two months later and Dr. Miami readily accepted, in part because he never saw a media opportunity he disliked.

“He also understood from the first block of shooting that I was more after his complexity and his religious side than I was after his funny skits,” observes Chartier. The film finds a fascinating complexity to Salzhauer’s life and work in which his devotion to his Jewish Orthodox faith is seemingly at odds with his business. At home, his wife is naturally beautiful and doesn’t sport one of the controversial Brazilian butt lifts that are Dr. Miami’s hallmark, nor are his kids actively using social media.

Chartier explains that retrieving this complexity to Dr. Miami’s life involved digging deeper each time he accessed his subject. “I got three blocks of shooting and in the first block of shooting, it was a lot of the funny things,” says Chartier. “He would roll his face saying things that he would have said to every other media.” The film offers some choice soundbites as Dr. Miami’s braggadocio star persona works the camera. “But as time passed, after my second block of shooting and my third block of shooting, he was able to understand was looking for,” adds Chartier. “He enabled me to go in new areas and shoot with his family, wife, and children.”

The multiple shoots accentuate the contrasts in Dr. Miami’s persona as he delivers his most boisterous interview while seated atop a golden throne in his office. The latter blocks of shooting reveal the extent to which the self-crowned king is just a character who enables Salzhauer to lead a relatively normal and comfortable life. Similarly, the director’s presence around the family inspired Salzhauer’s wife, Eva, to speak candidly about her feelings on plastic surgery (it’s not for her, Botox notwithstanding) and her dislike for the saucy lyrics that her husband’s social media celebrity inspires. Their daughter Aleah, meanwhile, is a near-luddite who thinks that one’s body is one’s temple, so one should be pleased with whatever size of butt, bust, or tummy God delivered.

“The interview with his daughter only happened the day before the last shoot,” explains Chartier. “She didn’t want to participate at all before, so that the fact that she went there, talking about how empty social media is and how everyone lives through the eyes of the other, that surprised me. She was talking in general, but she was obviously talking about her dad.”

Plastic Surgery as Pop Culture

When it comes to accessing Dr. Miami’s lab, Chartier says that the doctor’s constant livestreaming of operations didn’t necessarily make shooting any easier. “We never see the patients’ faces, except for one woman who comes for a consultation,” explains Chartier, noting how the scenes filming surgical procedures use careful blocking to respect patients’ privacy.

The exception is the aforementioned scene featuring a perfectly attractive and healthy young woman who arrives from Vegas and drops $16,000 on a bigger butt. Her scene plays like an audition for Dr. Miami’s social media feed as she poses while modelling the body she wants to enhance. “I would say she has a perfect body, but she wants a big butt because that’s the trend,” the director adds, noting how the scene reflects one of Dr. Miami’s many clients referred to him via Snapchat. The film captures the collision of attitudes of self-worth linked to idealised body images and potential for self-love enabled through enhancements and Instagram likes. The contradictions in They Call Me Dr. Miami extend from its key subject to the supposedly progressive and social media-savvy society of which it is apart.

For example, one clip among social media snippets is a video of a young woman who shares her dreams for plastic surgery and a perfect body—delivered while scarfing Popeye’s fried chicken and a giant fountain pop. Chartier recalls a fun process of scouring the web and selecting examples of the appetite Dr. Miami feeds. “Plastic surgery in Miami, Los Angeles, and other parts of the US is pop culture,” observes Chartier. “They talk about it. They show it. They’re proud of having plastic surgery. They’re showing a lot of skin, whether it’s on the beaches or social media.”

BBLs and Life-Threatening Lifts

Simply framed between Dr. Miami’s own contradictions, the videos speak for themselves. “There is one sequence where the young women are shaking their butts—twerking, as they say,” notes Chartier. “I’m portraying this as funny, but I think it’s more sad than funny when all those young women want to show us their butts and their breasts to be liked. To think they would go to any clinic to have a cheap surgery and that they could die, that’s pretty scary. That’s pretty sad.”

The film builds a dramatic arc with the social media videos as Dr. Miami voices his fear that a patient could die in his care. Chartier captures the doctor advocating on behalf of best practices after many woman treated by other doctors die during the risky Brazilian butt lift (BBL) surgery, a popular but dangerous procedure that involves removing excess fat from the body and transplanting it into the rear. The BBLs highlight the Dr. Miami’s ridiculousness as they bounce buoyantly in TikToks but they underscore his professionalism as he uses his platform to acknowledge the risks of going under the scalpel.

An unexpectedly tense scene sees Dr. Miami confront his fear when he’s called to save a patient’s life. The camera follows Dr. Miami through the corridor and waits in suspenseful pause while the doctor, still miked, assesses the situation. “That’s the kind of scene you don’t want to miss as a filmmaker,” says Chartier. “You don’t know what’s happening, so we’re in the same situation as everyone else, but there’s a grey line of what’s ethical. Dr. Miami was miked and his nurse was miked, so my sound man and cameraman kept rolling on the other side of the door.” The scene is suspenseful as one watches, imagining the unseen action, but proves a turning point for Salzhauer as a character as he demonstrates his ability to trade personas and assume the gravity a situation requires.

Selfie Culture and Camera Comfort

Salzhauer’s comfort in switching himself on and off for the camera further demonstrates the extent to which selfie culture shapes the relationship between subjects and cameras in documentary. While it’s no secret that a camera’s presence may influence a person’s behaviour, Chartier agrees that a new relationship is evident, especially south of the border. “All the time I was shooting in the US, I found that people wanted to be in front of the camera,” observes Chartier.

“I would walk in the street with a sound man and with a camera, and people would come to us and ask what we’re doing. ‘Can I be part of it? Do you want to shoot me? I have a story,’ they say,” explains Chartier. “Selfie culture accentuated the confidence that they have in the US. They all want to become ‘someone.’ That makes our jobs as documentary filmmakers shooting in the US much easier than shooting in Canada.” However, that process also involves observing a character’s awareness with the camera and his or her level of performance, as evidenced in the variations of Dr. Miami captured in the shoots at his home and office.

“Selfie culture is based on spectacle,” adds Chartier. “Since everyone is more aware of their self-image and as everyone is sharing more of themselves, then doing it in front of a bigger camera is becoming less of a concern.”

Entertainment and Ethics

Dr. Miami’s selfie culture panache ensnares him in controversy as his peers debate the relationship between ethics and entertainment. Although both Salzhauer and Chartier received consent/releases for patients featured prominently in the film, Dr. Miami includes interviews with no-nonsense surgeons who dislike the spectacle. The debate in the film echoes a similar conversation with documentaries about the relationship between ethics and entertainment. The conversation is alight once again with Tiger King and its own larger-than-life characters who entertained audiences during quarantine while the film itself drew ample eye rolling from the doc crowd for the ethics compromised in the name of spectacle. Dr. Miami admittedly feeds a similar impulse as Joe Exotic for audiences looking to scratch the itch left by the series.

Chartier relates to the hot-button nature of Tiger King and agrees that entertainment in documentaries is perfectly fine in moderation. He sees it as a chance to inspire audiences to explore the issues a film raises. However, he says that the complexities of Dr. Miami’s practice are inherently amusing and enlightening. “This is a character which is so big and loud and shows that about the world we live in,” observes Chartier. “If someone were to be entertained by this famous social media star/plastic surgeon, then they could be more reflective about the consequences of this world of images.”

They Call Me Dr. Miami screens as part of the Hot Docs at Home series Thursday May 14 on CBC and CBC Gem at 8 p.m. (8:30 NT) and documentary Channel at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

It also screens as part of Hot Docs’ online festival beginning May 28.