In Balanchine’s Classroom

(USA, 88 min.)

Dir. Connie Hochmann

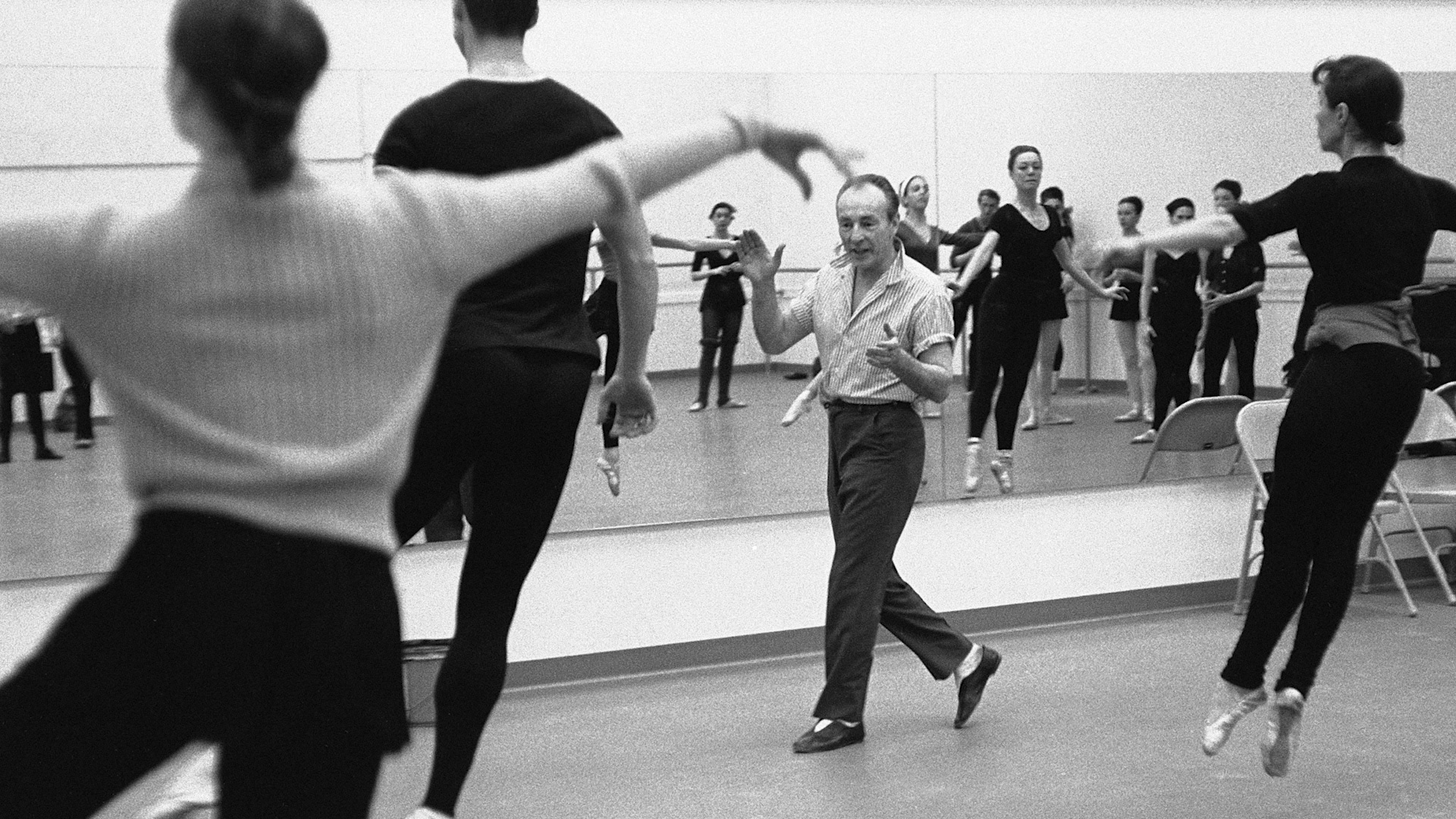

Towards the end of In Balanchine’s Classroom, one interviewee likens dancing with George Balanchine to fluttering on angels’ wings. Such hyperbole doesn’t extend to all the participants, but the celebratory air does. One sees why Connie Hochmann’s director statement refers to Balanchine’s pupils as “dancer-disciples.” The director, who studied dance at the New York City Ballet during Balanchine’s tenure, obviously shares her colleague’ esteem for their late mentor.

In Balanchine’s Classroom pays tribute to the late dancer and choreographer who helped make the New York City Ballet what it is today. Featuring interviews with many of Balanchine’s pupils, Hochmann’s doc unpacks the complexity of his dances and the even greater challenge of teaching them to a new generation of ingénues. This film deeply understands the art and technique of dance. Passion resonates strongly in the interviews as the dancers speak of for the painstaking perfectionism Balanchine demanded.

Archiving the Ephemeral

An impressive range of archival material complements the interviews. The dancers recall how Balanchine was fond of documenting his dances. The bravura of dances like Apollo impress, even on faded video. Archival footage taken in Balanchine’s classroom illuminate the rehearsal process. These are complicated works, as evidenced by the rigorous repetition the dancers endure.

Besides memories, these videos are often the only records that remain of Balanchine’s work. Dance, after all, is an ephemeral art. Moreover, any imperfections in the videos skew the record of his work. Each dancer remembers a number differently and they all emphasize the value of the details: how far to extend one’s fingers, say, or how rounded to curl one’s hand. Other dancers remember flubbing a number by performing it too “animalistically” when the choreography called upon them to be statuesque. The task of trying to spot the difference between performers is an amusing exercise that puts the broken telephone of Balanchine’s moves into practice. The degree that divides perfection and failure, however, is fascinating to discover.

While the archive often illuminates the laudatory interviews, it inevitably has a certainly flatness that leaves something to be desired. Live performances can translate relatively well if the camera is as dynamic as the dancers are, but these videos are mostly records. They’re static and they’re instructive, but they’re not cinematic. As a film, In Balanchine’s Classroom lacks movement, which is vital to any good dance doc.

A Ballet Empire

While the doc might not get audiences on their toes, it illuminates the effort entailed into building a ballet empire. Sequences about the foundation and development of the New York City Ballet illustrate Balanchine’s perfectionism, but also his sense of the immersive experience of ballet, the technical nuances of dance, and the role that environment plays in developing the craft. Dancers recall wearing hardhats while testing the stage during construction. Other interviewees note a specially designed orchestra pit tailored to the scale of his creative force.

In Balanchine’s Classroom inevitably slips into a narrative of a creative genius, but Hochmann doesn’t overlook her mentor’s faults. The dancers offer a chorus of moans about Balanchine’s exacting methods as he’d cry “Again!” “Faster!” “More!” throughout rehearsals. They recall how nothing was ever enough because he knew that the best dancers could make the extra leap. The memories alone conjure agony and exhaustion. However, nobody in the doc suggests they were broken by Balanchine’s methods. Instead, they articulate how his ability to push the dancers inspired them and strengthened them.

As the doc weaves between past and present, it sees many of these dancers now filling Balanchine’s ballet shoes. They teach his work with the same rigour. One sees his legacy endure as they command similar discipline from the dancers-disciples who now study in Balanchine’s classroom.

In Balanchine’s Classroom opens at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on Dec. 17.