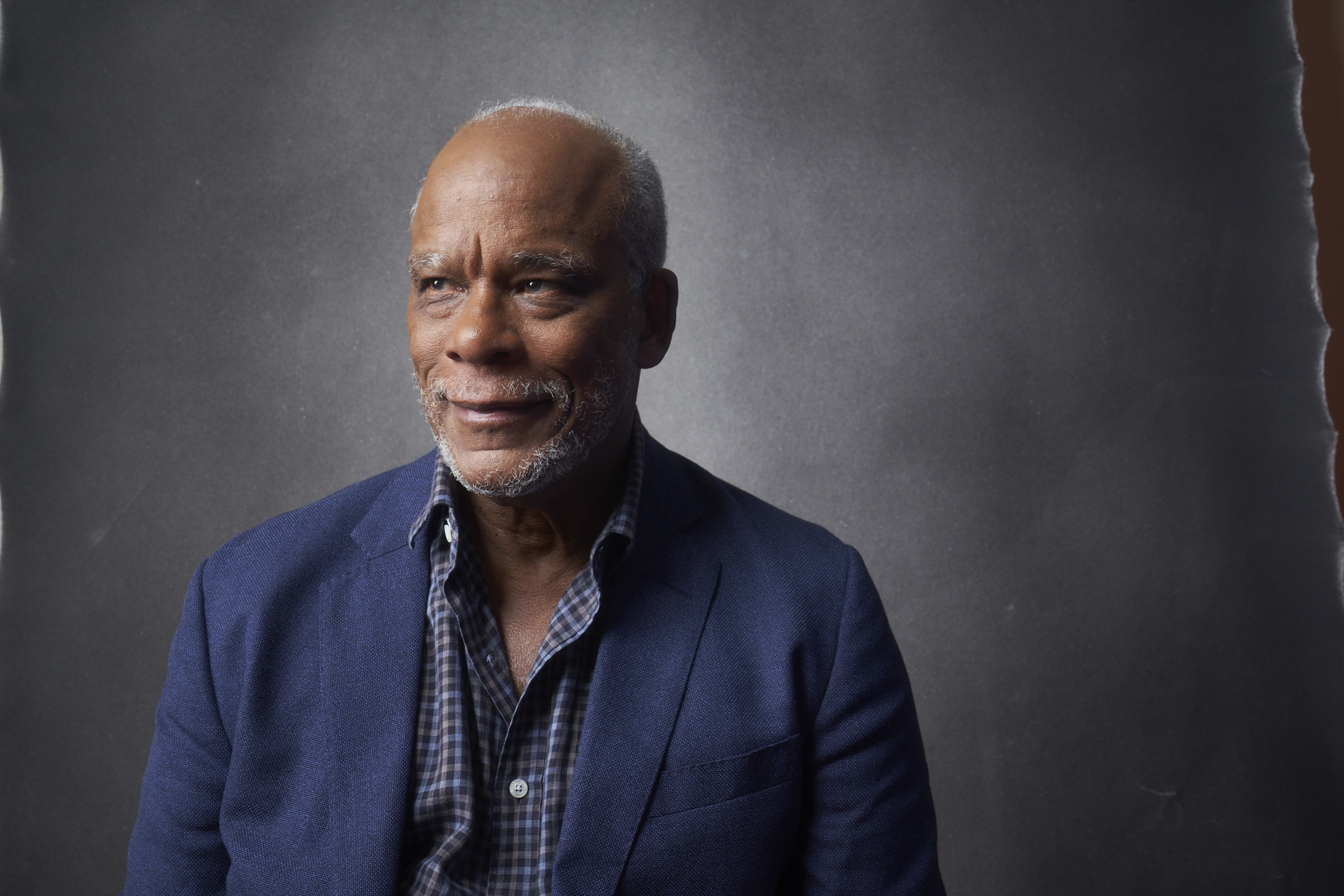

When connecting via Zoom with Stanley Nelson Jr. for our chat, it was impossible to miss his smattering of awards. In the background were a pair of Peabody Awards and the scythe-like wings of two Emmys, speaking to his decades-long career and the guiding light behind more than a dozen award-winning films. As our wide-ranging conversation about his career went on, one could spot more and more of these awards peeking out from various crevices and nooks in the background, illustrating the esteem with which the industry holds this documentary master. I was unable to spot his MacArthur Fellow “genius” prize, or the National Humanities Medal that was bestowed upon him by President Obama, but I’m sure they were in there somewhere, tastefully if deliberately placed to avoid undue notice.

Born and educated in New York City, Nelson has been a leading voice for non-fiction films on subjects as disparate as the murders at Jonestown to the activists that formed the Black Panther Party. With numerous productions screened as part of PBS’s American Masters series, his deep dives into topics requiring a sophisticated narrative touch combined with journalistic precision have justifiably been lauded throughout his career.

His latest film, Crack: Cocaine, Corruption and Conspiracy, is a deep dive into the culture of drug peddling and consumption that decimated much of the urban environments in the heyday of the so-called “war on drugs” in the 1980s. As the beacon of Firelight Media, Nelson has helped guide dozens of filmmakers, primarily from under-represented communities, and provided guidance and opportunity to foster generations of established filmmakers, creators and technicians to follow in his many footsteps.

In 2020 Nelson received the Hot Docs “Outstanding Achievement Award”, and in 2021 he is returning to give a virtual masterclass as part of their industry programme.

POV: Jason Gorber

SN: Stanley Nelson, Jr.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: When it comes to a topic like you cover in Crack, there’s usually a lack of journalistic precision when they’re telling a story that is so clearly easy to become grandiose. Can you talk about navigating this topic, by making something entertaining that still has journalistic integrity?

SN: Those two things guided us. These films are entertainment, so we were trying to get you there and hold you there, but the crack era is also a very complicated story. We started knowing that it goes from a user on the street, through the dealers, through the cities, through the federal government, and then the world gets involved. It starts out as a small story, but ends as a huge story. That’s what we had to navigate to tell this story and keep you with us every step of the way.

POV: Living through the era as a kid, it was obvious even then that there was a notion of class as much as race, echoed by the Whitney Houston’s “crack is whack” and “I don’t do crack, it’s a ghetto drug” phase. Do you think this divide is something specific to this era, or does that continue to this day?

SN: It’s really interesting because we were making crack in the opioid era. You see the opioid crisis being framed in a very different way. It’s now more often framed as a societal problem and not a criminal problem. We can’t ever say that the opioid problem is handled well, but it’s being handled differently, and it’s probably handled better.

POV: Can you speak about your decision to work in non-fiction filmmaking? You began by working with working with William Greaves and several other pioneers – can you talk about what the community was like then, and how you have shaped the telling of non-fiction stories over the last couple of decades?

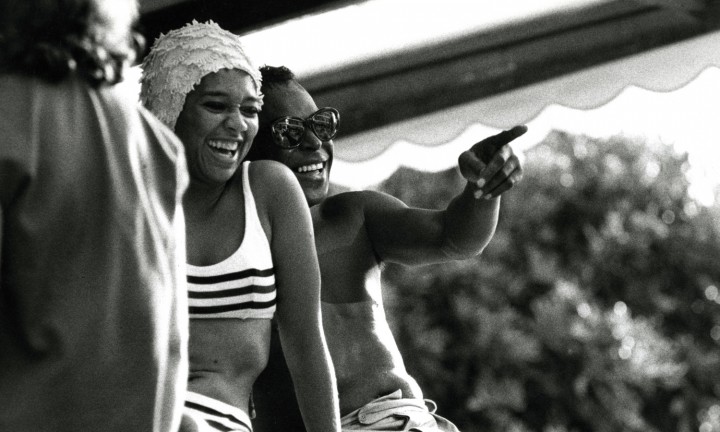

SN: I went to film school at City College New York. That’s my background, not schooled as a journalist, not as a historian, but as a filmmaker. I got out around 1976. That was a time when African-Americans were just getting into film. It was kind of the end of the Blaxploitation era and a few were getting into documentaries. There were programs to get different kinds of people working in the film industry, or working for PBS. Because it was the ’70s and because African-Americans had not really been involved in documentary filmmaking, those who entered in my generation really entered with a mission. I also think, and this is a huge thing, that we didn’t see a lot of money to be made in documentary. If you went to a party, and you said you were a documentary filmmaker, it’s not like the women would be like, “Oh, my god!” It would be, like, “Ok, I’ve gotta go get a drink. Bye!” A lot of people, especially African-American people, who entered into documentary filmmaking entered with a mission because there was not fame or fortune to be had.

POV: Let’s talk more in detail about you working with William Greaves. Given his enormous legacy, he’s underappreciated in many ways. Please talk about your working relationship with him and what effect he had. Why has his legacy not been upheld the way other filmmakers from the era are revered?

SN: William Greaves is a fascinating character. He’s an African-American man, and he wanted to get into filmmaking. He actually had a few parts as an actor in Black films in the late ’40s, such as Miracle in Harlem in 1948. He couldn’t get into filmmaking here [in the U.S.], so he went up to Canada and was part of the National Film Board. There he made a couple of films and was trained in filmmaking. He came back to the States and, when I joined him in the ’70s, he was the one African-American who had his own film company. He had an office on 57th Street and Broadway and he had a bunch of government contracts. That was when the government started wanting to hire minorities, and Bill was one of the only ones who had training and films under his belt. He did everything. He did documentaries for the Navy and the Air Force and the Marines. He did feature-length documentaries; he did feature-length films.

I think he was a producer on the Richard Pryor film where they were on a bus [Bustin’ Loose, 1981], and he did experimental films. I won’t even try to pronounce the experimental film that he’s most famous for [Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, 1971]. Bill did everything, and he was a real filmmaker. He edited, he shot, he worked the cameras on his own films, and he gave me a great opportunity. I was his assistant, and after about a month or two working with him, he arrived in his car and he said we were going to Atlanta to make this film on barbershops and that I was going to do sound. Then we worked on another film and I was assistant editor, and the editor quit. He said, “Ok, well, you just finish it. You edit it.” That was the kind of guy Bill was. If he saw, I won’t say talent, but industry in you, and saw that you were competent, he would push you up the ladder. I actually lived with his family in upstate New York for about a year and a half.

POV: Have you been that person to another generation in the way that he brought you in and gave you this opportunity? Are there specific filmmakers you’ve mentored that you want to highlight?

SN: I’d rather not name names, because there’s a tonne of people that I’ve worked with. We try to work with a lot of African-American people and minority people on the films that we do for Firelight Films. That’s a dirty little secret of the film industry – you might have a Black director of a documentary, but everybody else is white. We don’t do that. We try to hire people that look like us. That may be the only chance of them getting work. 10 to 11 years ago, we started the documentary lab program at Firelight Media and we’ve launched over 100 filmmakers. It’s a mentorship program, and we work with 10-15 people every year and they’ve won Peabodys, Sundance Awards, Emmys, everything. Other filmmakers that we’ve worked with have gone on to other films and gone on to be nominated for Academy Awards for their next films.

POV: Do you see a fundamental difference between a cinematic documentary and a television documentary?

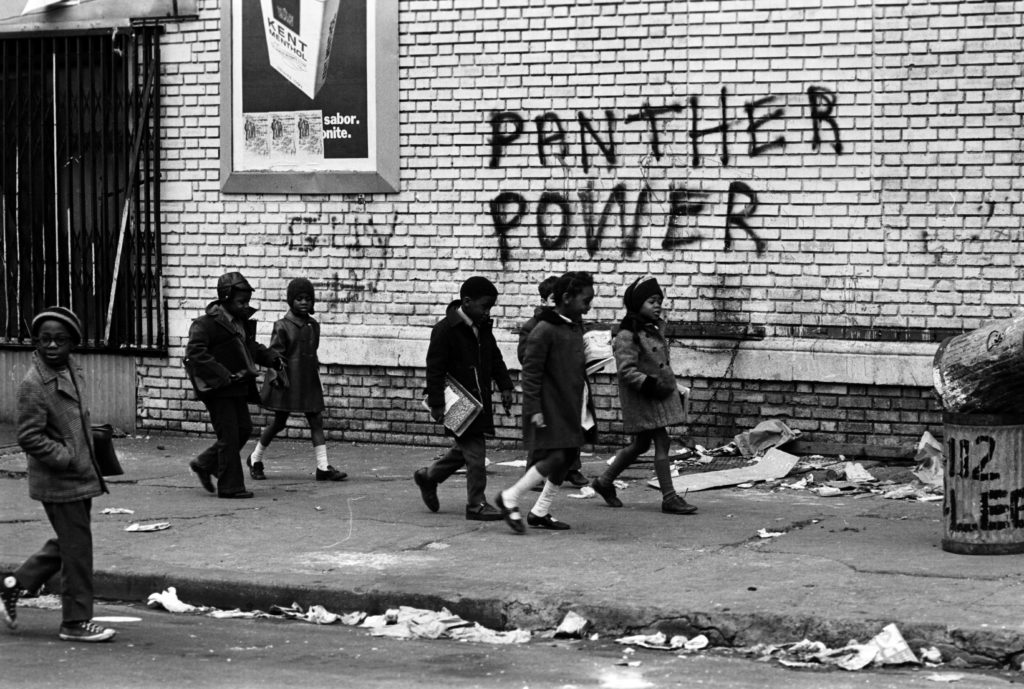

SN: No. None. I mean, a lot of people do, but we don’t work that way. One, it’s because of my training as a filmmaker; two, it’s from my history, breaking into the industry and people of my generation and still of this generation being on a mission to make films. We see this as a lasting document. The films that we made – Freedom Riders (2010), The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015) and Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool (2019) – might be the only films that are made on those subjects for 20 or 30 years. If you make a project on those subjects, the people who are involved are going to have passed away, so you can make a film, but it’s going to be very different. We look at these as lasting documents and we’re trying to use every tool in the book of filmmaking. We spend a lot of time editing, and I think that may be one of the huge differences. With TV documentaries, they’ll edit it in 10 weeks or 12 weeks. Louis Erskine, who was the editor of Birth of the Cool, spent 56 weeks in the edit room. A lot of times, the production fee for the company or my salary goes into spending more time in the edit room because our mission is to make good films. If you make money, then great! We think that if we make great films, then the money will take care of itself.

POV: You talk about having a mission, yet so many of your stories are ones of nuance. They’ll absolutely have advocacy elements, but you’re not making commercials for a particular point of view. Somebody as complicated as Miles Davis, something as politically ambivalent as the Black Panthers, something like the crack epidemic – the notion of who is a dealer, who’s an addict, what the systems are at play – avoid easy answers. Can you talk about navigating that through the editorial process?

SN: The most wonderful thing about documentary filmmaking occurs when the audience feels like they’re absorbed by the narrative and discovering the nuance to the story. Sure, we try to guide them and push them in certain directions, but we want them not to feel the push, not to feel the guidance. We’re just laying out a story. I really want to use every tool that I have in my filmmaking basket, but also to disappear as much as possible at the same time. The film is not Stanley Nelson’s opinion about the Black Panther Party. The film is not Stanley Nelson’s opinion about the Freedom Riders, or Jonestown. We want the film to be told by the people who lived it and by the footage and the documents that tell the story. I try to remove myself, but at the same time, I try to use every tool that I have to tell the story.

I would love to one day, and I will at some point, to go through a film like Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. If we just went through the first 15 minutes and talk about all of the stuff that we’re doing, it would be really surprising. We’re doing a ton of stuff, we’re throwing everything at you, and that’s something that we do on purpose. I always thought about films in that way, but more consciously recently. We’re trying to show you in the first five, ten minutes, all of the tools in the basket. Another filmmaker said to me, “I know you guys are doing the Black Panthers, and I hope you guys aren’t starting the film with a bunch of angry looking Black men with their arms crossed holding guns.” I said, “Well, now I’m not!” [laughs]. We consciously start instead with animation, with a story about an elephant and three blind men. We wanted people to look around, and if the film was premiering at a festival, and say, “Wait, maybe I’m in the wrong theatre,” because they thought there was going to be angry Black men with their arms crossed holding guns.

POV: You can have issues with political violence but understand where political violence comes from. People like Miles Davis don’t have to be saints, but they don’t have to be horror villains. On that point, obviously Chairman Fred Hampton had a fictional portrayal of him recognized with an Oscar for Judas and the Black Messiah. Do you have any reaction to how the biopic has taken over for many people as their introduction to the truths of these stories?

SN: It’s wonderful that the story of Fred Hampton and the Black Panthers is getting a wider audience and that the film is successful. It’s great that the film is good! I might have thought a little bit differently if the film was not so good. It’s a fine introduction, but there’s so much more to the Panther story and there’s so much more to Fred Hampton’s story. Anybody that liked Judas and the Black Messiah should seek out the story we tell with The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. We tell the story, with clips and audio of Fred Hampton, but what’s not covered in the fiction film is about how the police tried to cover the whole thing up. They even built a set to film their version of the story!

POV: You have lived through a period where any notion of objective truth, particularly journalistic truth, has been under attack. As a documentarian, you’re on the front line of that, As an African-American, you’re on the front line of the front line. How have the last few years shaped you as an artist and a man?

SN: In some ways it’s been very depressing, and you try not to be depressed. There is right and wrong, there is reality and fake, and it’s a moveable thing. A lot of people have been caught up in this weirdness. The whole COVID thing—it’s unbelievable now that we’re kind of creeping out of it, thinking, “Wait a minute, we walked around in masks for the last 14 months.” But also there is the whole Trump era. It’s just been very negative in so many ways, to tell you the truth. At the same time, the newspapers are getting thinner and thinner and smaller and smaller. It’s just a very strange time. People are getting their news from all different places, and some of them are real and some of them aren’t. It’s also been at a time when there’s been a rise in documentary, in the importance of documentary, but also in the appetite of the general public for documentaries, which is a good thing.

POV: As a voting member of the Academy, do you have any reaction to My Octopus Teacher winning? Do you care about what the Oscar for best documentary goes to?

SN: First, My Octopus Teacher is a really good film. It’s good. You can’t help but be drawn in and love it. But it’s hard for the Academy to give awards to anything that’s edgy, you know? When Vanguard of the Revolution did not make the short list, I was like, “What?” My daughter said, “Dad, it’s the Black Panthers, and it’s the Academy.” The Academy is trying to change, but it’s very hard. I’m a member of the Academy, I’m a voting member, but people are on there for life, so the voting members are 90 years old. Is it going to be Time, or is it going to be a warm story about an octopus? It’s just hard to change, but we have to understand that that’s what the Academy Awards are, right? Time won a whole bunch of awards. It got seen by millions of people. It’s a great film. Other films like that, I can’t remember all of the things that are nominated.

POV: Boys State didn’t even get a nomination!

SN: It’s too long to go into, but if you’re in the Academy, or you’re really into film and you’re dealing with that, you have to understand that the whole system needs to change. People are spending millions of dollars, sometimes ten times as much money as the film costs, to get an Academy Award nomination, or get an Academy Award. That’s the reality of it.