Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers’ new film Kímmapiiyipitssini:The Meaning of Empathy weaves together a broad portrait of the impact of settler colonialism on Blackfoot people, through firsthand experiences of people with substance use disorder, and the frontline workers who answer the calls to treat them. Her two-hour documentary aims to show how that impact is inherently tied to substance use disorder, but the trauma doesn’t define the people. Tailfeathers’ film starts in March 2015, on the Blood (Kainai) Nation in southern Alberta, part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, when it declared a public health emergency from opioid overdoses, and the community’s health care workers found themselves at the centre of an epidemic.

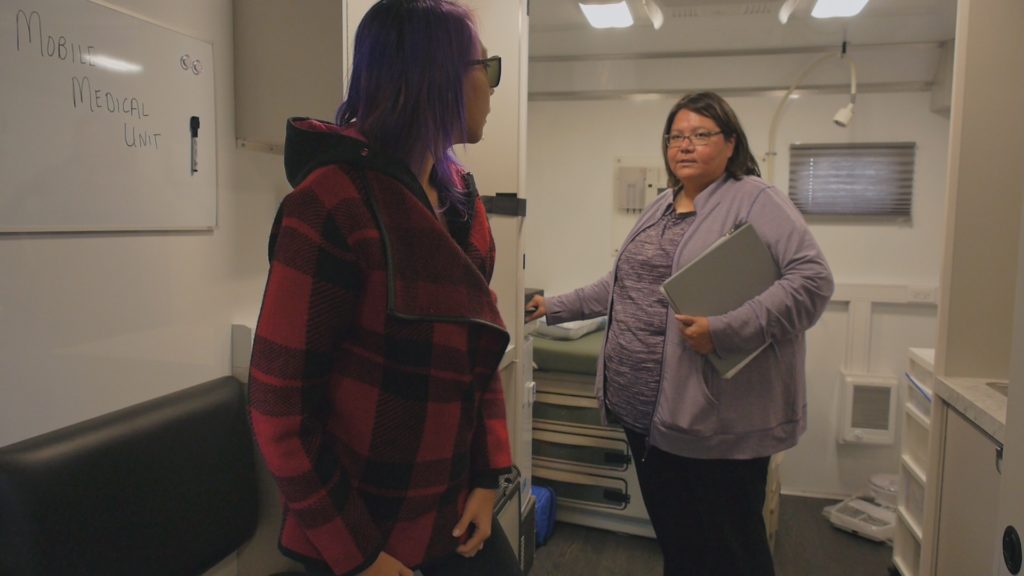

This affected two members of the Tailfeathers’ family, Dr. Esther and eventually her daughter, film artist Elle-Máijá. A family physician at the reserve’s medical clinic, Dr. Esther Tailfeathers is one of the healthcare workers who began investigating alternates to 12-step abstinence programs for substance use disorders. She journeyed to Vancouver’s downtown eastside organizations that offer harm reduction methods and a non-judgemental, more compassionate approach to drug and alcohol users, which provides them with safe spaces and clean equipment.

Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers, the co-director and co-star of the recent acclaimed narrative feature The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open, recalls feeling helpless as her mother was at the forefront of this crisis, hearing every day about what the doctor was witnessing. After carefully thinking about the situation, Elle-Máijá realized that she could use her filmmaking skill set to document her own community’s story and reclaim a narrative that was spinning further away from the complex reality of the situation.

“At the time that I started making this film, there were so many stories in the news media about my community, and a lot of them were framed from this trauma porn perspective, telling stories of sorrow, and grief, but leaving out the work being done in the community,” says Tailfeathers from her home in Vancouver.

“The same sort of imagery was used over and over again, shots captured on a long lens from faraway on boarded up houses that nobody lives in, or of people that were taken without their consent. It was really problematic and didn’t represent the community that I know and love.”

It was important for Tailfeathers to tell the story, as a member of the Kainai First Nation (she’s also Sámi), in order to counter several tropes: trauma porn, oversimplified portraits of drug and alcohol recovery, and the extractive way that Indigenous people are featured in documentaries. Her film offers a nuanced look at a community grappling with the best way to approach its drug crisis, considering that not everyone is willing to embrace harm reduction, while giving space to the people actively working every day to make a change.

She says that the general mode to approach addictions, which have been a struggle within Indigenous communities for a very long time, is with Alcoholics Anonymous or the Red Road to Wellbriety, the Indigenized approach to the 12-step sobriety and recovery programs. She observed a pushback in the community to the idea of harm reduction.

“It became very apparent that there isn’t one singular voice within my community in terms of experience, understanding or perspectives towards addictions and harm reduction in general,” says Tailfeathers. “I came to understand that there needed to be a really rich diversity of voices from within the community. I think that’s something that we often don’t see in documentaries is a wide breadth of voices.” Kímmapiiyipitssini also paints a full picture of the people who are more than their substance use disorder, including homeless couple George and Leah. Tailfeathers gets emotional, calling them “the bravest people I know,” who endure dehumanizing treatment every day. She considers it a privilege to be welcomed into their lives and that they shared so much of themselves with her.

“It was a tough journey in terms of wanting to represent them in a way that didn’t portray them as victims, or people who are homeless and addicted. They are so much more than that,” says Tailfeathers. “I think they have so much to contribute to our community. It’s just that living in such unfortunate circumstances where they face insurmountable barriers on a daily basis [is so difficult for them], and I don’t think people understand the gravity of their situation.”

The filmmaker says she was constantly considering how audiences would view the people of her community living with opioid and substance addictions, and that included her own privilege. While a community member, Tailfeathers says she’s never experienced addiction firsthand, lives in the city, is university-educated, and is middle class. “I don’t have to face the same sort of systemic barriers that a lot of my documentary participants have to face,” she says.

“I feel like Western audiences, or non-Indigenous audiences, almost feel a sense of entitlement to those types of stories of people’s pain and trauma,” says Tailfeathers. “I wanted to push back against that and show that it’s so much more complicated than the narrative that we often see on screen.” She felt a huge responsibility to be as generous and compassionate in telling their stories as they were with her. In the spirit of reciprocity, she also appears in front of the camera, as interviewer, chauffeur, and someone sharing vulnerable parts of her family’s experiences with grief.

Tailfeathers says making the doc was a masterclass in learning how to work ethically within your own community. Each documentary participant had the opportunity to share what they want people to know about the community, what it’s like living with substance use disorder, or what it’s like to work on the front line. In addition, she didn’t want the film to go out without everyone in the film screening it first, because of the vulnerabilities people were sharing with her. All participants saw the rough cut, with some takeout food in her mom’s basement, giving them a say in how they’re represented. (No participants asked for changes.)

Tailfeathers considers the divide between documentary filmmaker and its participants as the conventional Western way of filmmaking, and initially thought she should follow those protocols. “I realized very quickly that’s not how you engage with your own community and it’s impossible to remain objective or not become a part of the story,” she says.

The ethical decisions included choosing not to show any of the film’s participants in a state of intoxication, which she interpreted as a way of applying harm reduction to the filmmaking process. “That meant that a lot of the time, people that we intended to film were not in the right place to make those decisions and so we didn’t film them,” she says. “It was just the reality of the nature of the film. You can’t expect people with substance use disorders to show up completely sober and ready to film.”

It was important to depict them with a compassionate and non-judgemental lens, which was also a way to combat the trope of the drunken Indian, which is “ugly and painful,” she says.

Kímmapiiyipitssini took a year of development, research and relationship building, before Tailfeathers assembled her small crew to film. While the key crew was mostly non-Indigenous, something that Tailfeathers carefully considered, she ensured that everyone went through a two-day mandatory cultural competency training to give a deeper understanding of Blackfoot worldviews and protocols.

“There are inherent biases that that a lot of non-Indigenous Canadians have absorbed and a lack of knowledge about what we’ve been through and what we’re up against,” she says. “It was really important for me to be able to bring my crew up to speed so that when entering my community, they had an understanding that they, as non-Indigenous Canadians, are absolutely privileged to be able to enter and work with my community and there’s a lot of work that has to be done in terms of being on the same page.”

She also ensured there was always at least one Indigenous crew-in-training, in order to build capacity in the industry.

“When it comes to observational documentary, the DP needs to have a very distinct intuition and understanding of how to film people in a way that that feels natural, so I worked with Patrick McLaughlin who had experience, but I also wanted to make sure that we were training other Indigenous cinematographers in that,” she says.

Hans Olson, who edited Tasha Hubbard’s Birth of a Family and nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up, was the editor on Kímmapiiyipitssini. His past work with the Nêhiyaw (Cree) filmmaker put him in a unique position of understanding Indigenous stories, according to Tailfeathers. Their work together was impacted by COVID, interrupting the editing process when she believes they both contracted COVID.

Tailfeathers’ documentary overlapped a lot with the making of The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open, as well as acting in Blood Quantum, the horror film from Mi’kmaq director Jeff Barnaby. Tailfeathers says that pausing to work on the other films essentially helped Kímmapiiyipitssini’s pacing, by giving her more time with the documentary.

Time was also precious for the incredibly busy Dr. Esther Tailfeathers. Capturing her on film was tough; it was hard even for her daughter to get a moment and have her slow down. Initially she was going to be the main focus of the film, but it didn’t come to fruition, partly because of access, but also because the doctor wanted to acknowledge that she wasn’t doing the work alone.

“We had to find moments where [my mom] would let us jump in with the camera and throw the microphone on,” says the filmmaker. “She was concerned that we would paint a portrait where she was the hero, and so she was constantly resisting that.”

Despite the difficulties of pinning down filming moments with her mom, Tailfeathers says there was a lot of laughter and inspiration, following her around with a camera, and seeing how she interacts with patients and the community. “I’m immensely proud of her,” says the younger Tailfeathers.

While this documentary is about to be out in the world, hitting the festival rounds, including Hot Docs in Toronto and DOXA in Vancouver, this isn’t the end of Tailfeathers capturing intimate stories about her community.

Tailfeathers says she’s lived in Vancouver for 14 years, and a lot of her work hasn’t been at home. Kímmapiiyipitssini changed that. “Not to sound cliché, but it just felt like good medicine, to come home and work with my people. It was the most humbling process to recognize the power and strength of our people, and the beauty of our land and that is something I will treasure for the rest of my life,” she says. “I really hope to be able to continue to tell stories within our own communities.”

Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy screens at Hot Docs and DOXA.

The film has a Hot Docs Master Class on Saturday, May 1, at 5:00 p.m. ET with filmmaker Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers and Dr. Esther Tailfeathers.