Part of the appeal of true crime documentaries is their ability to turn viewers into armchair sleuths and jury members. One minute you’re donning your deerstalker hat and embracing your inner Sherlock Holmes, dissecting the who and how of a crime, and the next minute you’re sitting yourself down in the jury box, forming a judgment of guilt or innocence based on the testimonies of witnesses. What audiences often neglect to question, though, is who gets to be considered the authoritative voice in the courtroom, and how the very framing of the question—guilty or not guilty—leads the jury down a particular path.

In Sherien Barsoum’s riveting new documentary Cynara, a criminal justice system that gives more consideration to certain professionals than it does to members of minority communities is put on trial. “That is a central question for me…Whose voices do we believe? Whose voices do we give credit and value to?” states the director. During her investigative lens toward the mysterious events surrounding the tragic death of 16-year-old Cynara Ali, who was born with cerebral palsy, Barsoum crafts a richly layered film about Cynara’s mother Cindy’s attempt to clear her name within a flawed justice system.

As the film unfolds, it becomes apparent that the scales were weighted against Cindy long before she set foot in a courtroom. According to Cindy, on February 19, 2011, two masked men showed up at her home demanding a mysterious package. By the time the men left, Cynara had stopped breathing and Cindy was on the floor, drifting in and out of consciousness. Despite recounting the harrowing tale to numerous police officials, it did not take long for the mother to become the prime suspect in the investigation of her daughter’s death. Muddying the waters even further was the emergence of a letter that arrived three weeks later, allegedly from the assailants, stating that the wrong house was hit in error.

Unbeknownst to Cindy, the accusation of guilt had been squarely placed on her back shortly after the first responder on the scene, a firefighter, entered her house. Dismissing the notion of a home invasion, claiming there was snow on the ground but no footprints leading into her home, the firefighter became suspicious of Cindy once he saw that Cynara was lying awkwardly on the couch. At the trial, he testified that he believed Cindy was faking her injuries, because she did not project any internal pain and said “ouch” when he pinched a nerve.

While the thought of Cindy having to be performative in her distress, as if auditioning for the lead in a macabre play, is unsettling, it is not as disturbing as the firefighter’s belligerent actions towards her. Wanting her to move, so he could tend to the teen, he proceeded to kick her foot and yell at her. Despite these actions, his assessment regarding the home invasion both helped to point the police investigation down a narrow road and carried significant weight at the trial. In the courtroom, it was his testimony, and not that of an Asian woman who saw two men fitting Cindy’s description around the complex, that was held in higher value.

Factor in the trial judge’s charges for the jury, several of which implied presumed guilt, and it is easy to see why the jury found Cindy guilty of first-degree murder. Cynara uses Cindy’s appeal case to dismantle the firefighter’s testimony, including evidence that there was no snow on the sidewalk that day, debunking his footprint claims. The film shows how the judge prejudiced the jury, charging them to consider the case with an implied presumption of Cindy’s guilt and offering only two possible causes for Cynara’s death. It makes a compelling argument that Cindy was a victim of a legal system unwilling to see beyond its preconceived notions.

As if attempting to sculpt the image of a grand monster from the thinnest piece of clay, Cindy was vilified in the media and the courtroom with little evidence to back up the claims. Although eventually convinced a miscarriage of justice occurred, Barsoum admits to having her own doubts at first, due to the negative press surrounding the trial. “I was really skeptical about her story because what was available to me was that media coverage,” she recalls.

Originally approached by the mother’s community to tell the story, it was meeting Cindy’s husband Alan, their three other daughters, and members of her devoted church family, who never wavered in their support, that drew Barsoum to the case. A trained journalist, the filmmaker immersed herself in the trial transcripts and uncovered several glaring gaps in the Crown’s case against Cynara’s mother. “For me, wherever there are questions, there is an opportunity for an interesting story,” the director added.

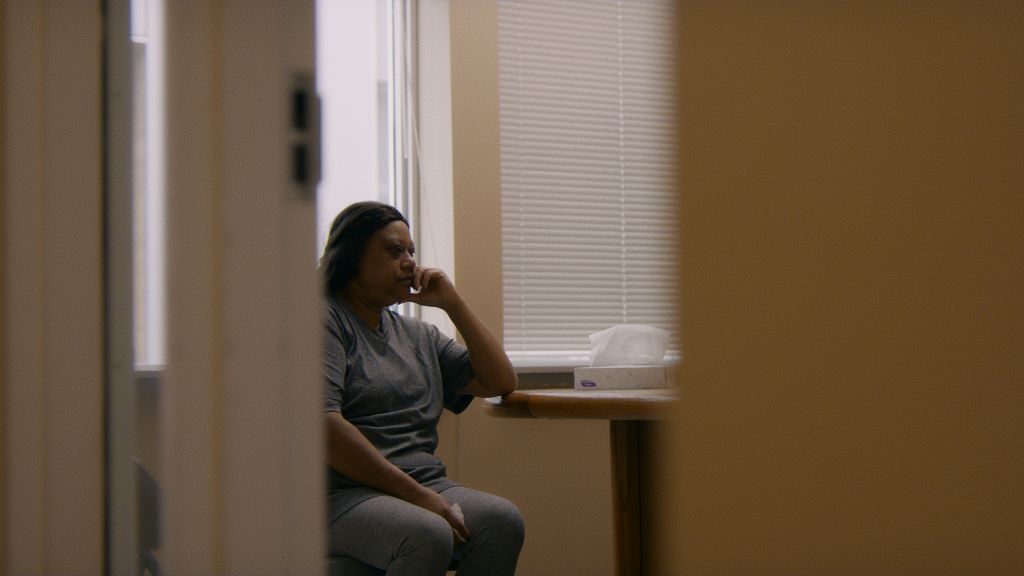

By the time producer Bryn Hughes and executive producer Michelle Shephard came on board, Barsoum was convinced Cindy had been wrongfully convicted and had filmed some footage with the mother in prison. However, the producers were not immediately convinced. Their initial skepticism added an additional layer of scrutiny that was needed for a film like this. “I think having us onboard just to poke holes in her theories was important,” states Hughes. While the facts ultimately supported Barsoum’s thesis, presenting them to audiences created its own set of challenges.

As documentary filmmakers do not have access to film in Canadian courtrooms, Barsoum had to find a compelling way to recreate key moments in the trial. “We knew it had to be in a way that really brought viewers into the moment and its emotion,” she states. Using trial audio recordings and transcripts, Cynara employs the tableau technique from the world of theatre to create visually stunning re-enactments. “The actors literally froze. We told them not to blink, not to breathe, until our camera got past them and then the camera would flow through the moment,” Barsoum recounts. The effect is mesmerizing, as it forces the viewer’s mind to be in constant motion, reflecting on and reassessing previous images as new information is revealed.

Like the faces of a Rubik’s Cube slowly being moved into place, Cynara methodically plays with time and revelations to bring into focus a powerful image of injustice. Although Barsoum and editor Rich Williamson mapped out the events chronologically in order to better understand what happened during the trial, the filmmaker admits that there are two stories unfolding in the film. “There is the story of what happened from the day the first responder entered the house up until the verdict, and then there is the unfolding timeline of our filming, which is Cindy’s incarceration through to her appeal,” Barsoum notes. Her film considers “all the things that followed and happened in between.”

While Cynara is filled with insightful interviews with the likes of Toronto Star reporter Jim Rankin and Cindy’s lawyer James Lockyer, those with Cindy and her family resonate the most. Painting a vibrant portrait of a family struggling to rebuild itself, the film has thought-provoking things to say about the immigrant experience, the various ways one’s faith is tested in the face of tragedy, and society’s inherent biases against those with disabilities.

“A huge part of the Crown’s case against Cindy was that she stopped loving her daughter,” Hughes states. Despite not having any concrete evidence to support these accusations, they continued to push the idea that Cynara’s disability was a burden and Cindy’s motive for ending her life. Through candid interviews with Cynara’s sisters, Barsoum systematically shows that the teen was loved by her entire family, with each member doing their part to help care for her.

In documenting the love and resilience of the family, Cynara disassembles the narrative of the Crown’s initial case and questions those who shaped it. While there are some lingering mysteries, in particular the authorship of the letter, the film makes it clear that an injustice took place in the initial verdict. Cindy’s experience serves as a reminder of the imbalance of power in Canada’s justice system when it decides whose words are to be considered gospel and whose are to be dismissed, especially when dealing with racialized and immigrant communities. Barsoum’s film serves as an effective warning of the dangers of such an imbalance.

Cynara screens at Hot Docs 2023.

Get more coverage from this year’s festival here.

Update (Oct. 21, 2023); Cynara airs/streams on TVO beginning Oct. 22.