“Why can’t you just leave me alone?”

– Oscar-nominated animator Ryan Larkin, shouting at the screen during one of the first public showings of Alter Egos, the documentary about his history, art and character.

Documentary biographies have become so formulaic in their celebration of individuals’ achievements and fame that if someone makes a film portrait that deviates from a straight forward celebration—if it is about notorious failure instead—should it be called an anti-biography? Ryan Larkin was a filmmaker himself and, once, could have made an autobiography. He was among a crowd of animators who pioneered new techniques with a legacy of films that influenced a generation. What separates him from this crowd and wins him attention these days are the brackets of misfortune at either end of his remarkably productive decade. Ryan has become a panhandler on Boulevard St. Laurent—“The Main,” Montreal’s most notorious street. He’s already in the gutter, some would say, so the challenge I faced was how to make a film that refuses to kick him when he’s down.

I’m riding the train to Montreal as I write this, to attend the 33rd Festival du Nouveau Cinema, and it feels like a kind of homecoming. I didn’t grow up in Montreal, but it does feel like I’m returning to the source: I made my first serious attempts at movie making here in the early 1990s as a cinema student at Concordia. I also made what is most likely the best film of my career, Reconstruction, while living in Montreal. Unlike my new film about Ryan, Alter Egos, Reconstruction wasn’t set here, but I made it in Montreal, editing in my apartment in the “plateau” district on a discarded NFB flatbed. Alter Egos is a co-production with the Film Board—that other ‘Je ne sais quoi’ about Montreal—which makes this trip feel like coming home to the birthplace of Canadian documentary. All of which conspired, I think, to force me to make Alter Egos as much about filmmaking itself as it is a film about Ryan, his creativity, his psyche and his tragic fall from grace.

Even though I’m a film academic, I’m not usually fond of films that are as much about their own making as their subjects. (Oh yeah, what about your film, Thin Ice? protests my own alter ego). However, in addition to making Alter Egos about the once-famous filmmaker Ryan Larkin, I was also making the film about Chris Landreth, a now-famous animator in the middle of a decade not unlike the one that rocketed Ryan to stardom in the 1960s. And Chris’ current project is a 14-minute CG (computer graphic) animation about Ryan, called Ryan, so how could my project be anything but self-reflexive? Adding myself to the mix except in the pre-credit prologue would have been one filmmaker too many, though; I didn’t want the film to end up being about me. Nonetheless, even if I don’t appear in Alter Egos, I implicate myself and don’t escape unscathed; if Chris sustains a critique for possibly exploiting Ryan, I’m just as guilty. Tiptoeing through this minefield was torturous and unsettling, and it has changed me in ways I’m not sure I yet understand.

I saw two documentaries during the making of Alter Egos: Stevie, directed by Steve James, and Finding Bryon, directed by Josh Adell and Steve Hicks and both these features made me ask why anyone ever agrees to let documentary filmmakers chronicle their lives. What’s in it for the subjects? I really can’t say why Chris Landreth and Ryan Larkin let me point a camera at them. But I can guess at one impulse they might have been feeling—a longing to get hold of something genuine, something authentic in an age when so much seems virtual or fake. The surge of public interest in documentaries, whether they are in theatres, on specialty channels, or even in the twisted travesties of Reality Television, springs from a craving for a Cinema of Honesty, and that’s a worthy aspiration in any era.

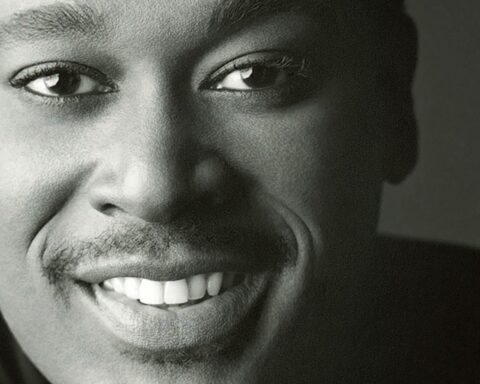

Ryan speaks for himself in the documentary, and is more profound and articulate than people expect. While the features of Landreth’s CG version in Ryan are meant to telegraph all kinds of psychic wounds, in my interviews, Ryan’s face is so expressive that undoctored close-ups and his stammer speak volumes about the guy’s fragile insecurity. We equipped Ryan with a DV camcorder, both to try to capture his unique perspective and to give his creativity an outlet again, but ultimately what is inside Ryan’s head is far more interesting these days than what he sees with his eyes. The hardest task was getting Ryan to fully disclose his memories and observations, buried under a lifetime of denial. As he himself rants, “I don’t want to talk for hours in front of cameras about me and my sordid past, or my glorious past, or any past—I live in the present!” Others, like Ryan’s old girlfriend, Felicity, and Tanya Tree, a fellow filmmaker from the NFB, as well as his old executive producers, Robert Verrall and Derek Lamb fill in some of the gaps, but I never managed to fully put the disintegrating Ryan Larkin back together again.

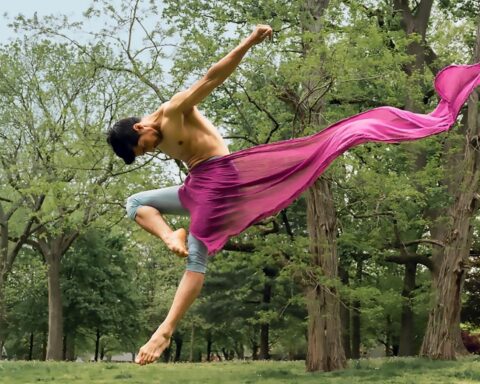

My doc also tries to get under Chris Landreth’s skin, but he has only a supporting role to Ryan’s lead. Chris is enjoying the film festival circuit where Ryan was once a star, but Landreth’s way of working, with a crew of render wranglers and character modellers and a studio full of high powered computers, demonstrates just how far behind the world of animation has left Larkin. Chris confesses to reluctantly inserting his own story into his short film Ryan, as well as agonizing over whether he’s taking advantage of Larkin’s misfortunes. He even worries about whether his mentor will approve of his mastery, but what is most disturbing are the moments when Chris very honestly stands in as an every man for every documentarian. Landreth admits his main goal is selfish, to make a good film and tell a good story, and clips of Chris’ earlier work reveal more about the parallels between these two guys, their egos, and their self-loathing.

At one point, Ryan calls himself a genius, a label rarely self-applied and more commonly bestowed by others, and in a parallel moment, Chris brags about being in Oscar contention and feels the need to explain that he’s “not God.” There are moments when both are remarkably at ease with themselves, but these are quickly matched by a slippery instability that lurks behind both men’s scarred masks. Ryan’s world has shrunken to a handful of city blocks that hero mantically guards with a queer inversion of Woody Allen’s Manhattan, and Chris bravely stares into the mirror, interrogating why he’s so haunted and confounded by Larkin’s tragedy, and finds himself faced with digging into his own family history for answers.

There was a time when Ryan was the epicentre of a bohemian salon lifestyle on Avenue du Parc during the heyday of the counterculture, but the adulation he enjoyed at his peak became an unsupportable addiction. This fall’s Montreal Festival screenings, and even the attention of the film crew during production, has revived his craving and supplied the new fix. As filmmakers, we have turned into his enablers and the preening prima donna is drunk on fame and its promise, once again. Chris Landreth attended the Montreal screenings as well, and surely feels the same mix of hesitance and delight every time the film screens. Its triumph of exposing vulnerability can only be bittersweet for Ryan and Chris, the two on frank display.

It was a little like a circus at Excentris, with Ryan revelling at his own masterpieces on the big screen again, but the familiar faces in the crowd helped settle him down. Norman McLaren should have been there, the master who spotted Larkin’s talent back in 1963, but he and Guy Glover are survived only by Grant Munro, the last of that inner circle at the NFB (Munro is the guy on the left in Neighbours). Munro declined to be interviewed when I approached him last year, certain that such a project was doomed to be squalid and exploitative, but after his touching reunion with Ryan after the screening, he raved about the honesty, integrity and intimacy in Alter Egos and even regretted his refusal to be part of the film—an incredible compliment.

In the intervals between shooting over the last eighteen months, Ryan missed us, and the camaraderie of the crew, but when we’d return to set up our camera, he’d quickly tire of our questions and close-ups, and send us packing. The same cycle repeated itself after the Festival screening as we prepared for another departure and Ryan found himself begging, “don’t leave me alone.” He derives the same comfort from his panhandling rituals and repetition that at one time came from the endless single cell drawings he did as an animator, but just as then, there are times when he wants to escape. When the limelight fades, the fact is Ryan is left alone to contemplate his present and his future, and prefers not to think about his past with those skeletons that Landreth so artfully animates. Ultimately, the collage of Alter Egos coalesces not around a portrait, or even a diptych, but around an investigation of the documentary form itself. With every film, I ask people to trust me with their image, their story, their reputation. This is a serious responsibility but rarely have I made a film that my subject actually liked—the outsider’s perspective of a director can reveal sides of people they’ve perhaps almost never confronted. In the case of both Ryan and Chris, I think I captured a few of these moments through their armour…and I use that word “captured” deliberately, because there is certainly a dimension of the hunter and the hunted in making docs.

While wrestling with two other filmmakers as subjects, it was obvious that they bristled at being on the other side of the camera for a change. No portrait can ever be complete or definitive, of course, but the demands of broadcasters push us ever further towards simplification and caricature, and filmmakers like Landreth and Larkin know this. I think documentary profiles usually tease out egos that can never make peace with being fixed for posterity in a single moment, from a single vantage point. Ironically, Ryan is so dignified and conscious of “who or what I really am,” as he says, that he has no problem whatsoever with the finished film, and called it “spectacular”—the greatest reward I could ask for.

Chris was equally pleased. Given the chance, would Ryan do it all over again? Would Chris? There ain’t a shadow of a doubt in my mind. I’m sure they would.

Given the chance to do it all over again, would I?