“Most of the elders in this community have never seen a feature film before,” observes The Territory director Alex Pritz. “Given that, how do you have an honest conversation about what a film is what it means to say yes to being in a film?”

The Territory, which opens in theatres this week following an acclaimed debut at Sundance where it won both the Audience Award for World Cinema – Documentary and a Special Jury Prize for documentary craft, navigates a complicated situation with expert skill. The film depicts the plight of the Indigenous Uru-eu-wau-wau people in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon. They’re fighting to protect their homeland, sustainable ecosystem, and a way of life from rampant deforestation. Settlers attack the rich territory of the Uru-eu-wau-wau in violent land grabs with devastating consequences for the tribe and the rainforest. In chronicling the tribe’s effort, The Territory flips the colonial narrative by putting the cameras in their hands.

For the New York-based Pritz, who studied science at McGill University in Montreal, The Territory presents a chance to engage with environmental concerns visually. “I thought I could take the issues like community-led conservation and try to apply them to the wider world,” explains Pritz. “The reason I got into science and conservation work was being out in the world—talking to people and field studies.”

“Flipping the Camera”

Pritz admits that convincing the Uru-eu-wau-wau was complicated since few of the people had seen a film. However, he says he embraced the challenge. “The Uru-eu-wau-wau community, especially the elders, are really skeptical and suspicious of outsiders, white people, white Brazilians,” notes Pritz. “There’s so much that’s been taken from this community by outsiders, so they were suspicious of me to start.”

To aid the situation and inform them about what being in a film entails, Pritz explains that he devised film workshops to engage the Uru-eu-wau-wau in questions of craft and representation. “The only way to open up that conversation was by bringing some cameras to start,” says Pritz. “I brought a small camcorder and we used that, not as a tool to teach people how to make films, but as a tool to open up conversation. I said, ‘You point the camera at me, I point the camera at you. You can interview me about my life: ask me why I’m here making this film. Ask me what I think this film can do.” In doing so, Pritz observes that this engagement with the Uru-eu-wau-wau collaborators embedded narrative autonomy in the storytelling. “Flipping the camera around levels the playing field in terms of the power dynamics,” adds Pritz.

The Territory follows several members of the tribe, most notably then 18-year-old Bitaté, whom the tribe elects as leader during filming, and Ari, a force from the Uru-eu-wau-wau surveillance team. The film observes as players from the 200-member tribe research the invasions upon the 7000 square kilometres of rainforest in Rondônia state that form Uru-eu-wau-wau territory. They use drones to survey the devastating deforestation and monitor fires set by the invaders.

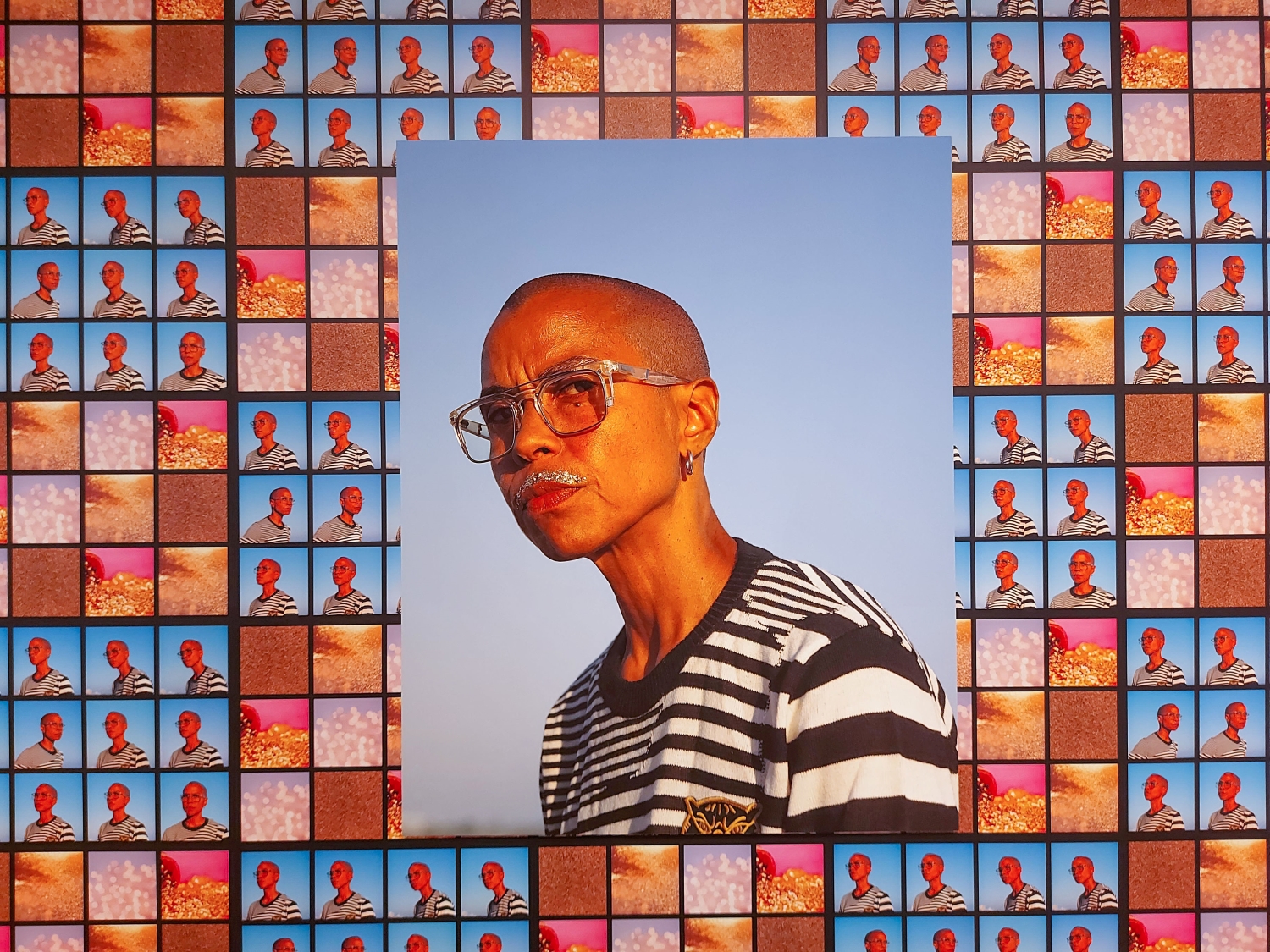

Tangãi Behind the Lens

At their side is Tangãi Uru-eu-wau-wau, one of The Territory’s credited cinematographers. The participatory philosophy that drives the film lets members of the tribe like Tangãi frame their story. Tangãi, a teacher in one of the territory’s schools, has a natural eye for observation. “I think being a teacher makes you a really good student,” notes Pritz. “He was attentive and he showed up.”

Pritz says that Tangãi was a constant during the workshops that his team did during production. “We’d take a Brazilian film and chop it up and say, ‘Okay, here’s an establishing shot. Here’s how they move through this scene. Here’s how they portray Indigenous people in this film.’ We’d ask how they feel about that. What could be better? What could be different?” explains Pritz. “Tangãi showed up to every one of those lessons. He was really dedicated to learning and improving his craft.”

Finding Significance in Scale

The Territory is visually striking as it weaves between imagery of the conflict on levels both macro and micro. Shots create parallels between the tribe members traversing the forest and armies of ants scurrying through the leaves. There’s a sense of harmony in this rich environment.

“This story exists as a localized, tightly knit conflict. Everybody involved in the film is connected to all the other characters, but it’s emblematic of what’s happening across the Amazon, and what’s happened throughout history in the United States, Canada, and other colonial countries,” says Pritz. “We wanted to convey that historical, ecological breadth, the scale of the destruction of the rainforest, and these patterns over history while showing these nuanced individual lives.” Shots of caterpillars crawling leisurely, say, give way to satellite imagery of roads chewing through the forest. “These geographic scales might help you think about the connections between this story and what you’re seeing and your own life, the land that you grew up in, and everything else that’s happened—this wider story that we’re all part of.”

Shaping the Story Collaboratively

The story also takes shape through the feedback of the participants. The Territory laudably gains access to players from both sides of the situation. That’s not an easy task, especially as the settlers who invade the territory expand their empires through illegal, often violent means. Pritz says the suggestion to include settler perspectives came from Bitaté and film subject Neidinha Bandeira, a Brazilian activist and ally of the Uru-eu-wau-wau, who introduced the director to the tribe. “Audiences aren’t going to understand the source of this conflict and this violence if they’re only hearing from people who are trying to defend the forest,” Pritz recalls them telling him. “They told me that audiences need to hear from the people who are out there with impunity, lighting fire to the forest.”

The Territory features candid interviews with settlers like Martins and Sergio. The men establish a neighbourhood association, Rio Bonito, to begin a paper trail in effort to legitimize their claims to Indigenous land. These interviews reveal the hardships the men face. They explain how economic necessity forces the land grabs as they set up shop for cattle farming. Footage from the frontlines of the fight observes as the invaders set fire to the forest and raze the trees of the dense ecosystem to facilitate road access and clear land.

“What helped us breakthrough was that they see themselves as pioneering heroes,” says Pritz on bringing the settlers into the story. “We allow them to express that point of view while filming them as they’re digging holes in the baking hot noon sun. That demonstrated to them that we weren’t just interested in filming the illegal parts of their lives, which we did film, but while widening that to get a fuller range of their experience.”

Navigating Trust and Safety

While the dual perspectives ratchet up the film’s tension, they also fulfill Bitaté and Neidinha’s suggestion that they could open up the story. “They think they’re doing a virtuous act of progress for the country,” says Pritz of the settlers, “and that they should be celebrated for creating something out of nothing–creating private property from wilderness. That’s what the whole country was built on.” The fight for the territory is a microcosm of the ongoing history of colonialism itself. In bringing both sides into the story, The Territory sees fundamentally incompatible worldviews collide. The capitalist systems that drive the devastation of the rainforest aren’t doing men like Martins and Sergio any favours, and the Uru-eu-wau-wau pay the price as the settlers seek any means to bolster an unsustainable future.

In telling both sides of the story, however, Pritz says he and his team had to navigate the responsibility that came with access. “Everybody was trying to get information from us all the time,” admits Pritz. “The environmental police would text us to ask, ‘Where are you?’ or ‘What’s going on?’ if they’d seen our car with some of the invaders the day before.”

Moreover, Pritz says the invaders would inevitably prod for scoops on the where and the what of the Uru-eu-wau-wau. “For ethical reasons, but also for security reasons, we had to keep a clear need-to-know basis for information within our team,” explains Pritz. “The last thing we wanted was for anybody to have to lie. If I was with the invaders, and I knew some information about an environmental operation that was going to go arrest some invading farmers and I didn’t disclose that to them when they directly asked me, they would think I was a spy. That would put me in a really dangerous position with them.” Eventually, parties learned that no information would or could be shared, and trust(ish) followed.

Tragedy and Agency

The Territory features two key narrative turns that leave a viewer rattled as the story illustrates the gravity of the fight. From a kidnapping scare to a fatal attack on a tribe member, the cameras offer immediate accounts of the immediate personal risks. Pritz, still displaying the toll of those events when asked about them, says he wasn’t in Brazil at the time of the murder because it happened at the onset of the COVID outbreak. “All those scenes were filmed largely by the local community themselves,” explains Pritz. “They’ve never filmed a funeral before. That just doesn’t get recorded in their culture, so I wouldn’t have been able to film that even if I had been there.”

The combination of participatory filmmaking and altered circumstances created by COVID affords The Territory firsthand access to the community in a way an outsider wouldn’t receive. Pritz says the circumstances necessitated new conversations about how to frame the footage moving forward, but also how to use the footage they’d already shot because the tribe does not depict death nor speak of the deceased by name. “The decision to be able to include images of [the deceased] while alive beforehand was difficult for the community,” observes Pritz. “We talked for days about what the value of this would be in terms of trying to seek justice, but then also what the cost is to their culture.”

The film sees them negotiate the significance of representing the deceased through images of protest, ultimately drawing attention to the cause for which his life was taken. “That was a decision they had to come to on their own,” adds Pritz. “I could be there for it, but couldn’t influence that at all.”

Activist Filmmaking in Fine Form

As the situation progressed, and ultimately changed due to COVID, Pritz says his team did sanitized drops of cameras and worked with Tangãi and others to tell the story without making the territory vulnerable to outsiders amid the pandemic. If not for the early practice of flipping the camera between collaborators, many of the film’s thrilling and urgent images simply would not have been captured. The teams coordinated logistics, and developed the film by demonstrating the need for shot lists and establishing shots to help create coverage and ensure narrative flow.

“It felt like we were still missing some important scenes, a key one was an arrest of an invader,” notes Pritz. “I’d been on half a dozen different surveillance missions of a week or so, but arrests were never caught on film. We told them it was an important scene to be able to show them doing their work in action. Bitaté totally delivered.”

Moreover, the Uru-eu-wau-wau crew eventually sold their story to media outlets, ultimately expanding the reach for their case and putting pressure on officials who were willing to let the invaders’ efforts slide. As The Territory brings this urgent story from the Amazon to screens worldwide, and offers a new model for participatory filmmaking, one would be hard pressed to find a better example of activist cinema this year.