Michèle Pearson Clarke knows heavy emotions. Grief, for instance, is a theme that has wound its way through her work, most explicitly 2015’s still-video installation, “Parade of Champions,” which confronted queer, Black grief in the face of losing a parent.

“Muscle Memory,” Clarke’s first major solo exhibit currently on at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, deals with the themes of loss, fear, and the vulnerability of being masculine in a Black, queer, female body. It consists of a collaborative video installation, “Quantum Choir,” and an accompanying self-portrait series, “The Animal Seems to Be Moving.”

“The older I get, the more comfortable I get with myself,” says Clarke. “Doing a project like this and leaning into that vulnerability is not something that I think I would have been ready to do earlier, but I’m at a stage now where it becomes possible.”

Clarke is referring to the extensive creative process behind “Quantum Choir,” a four-channel video and sound installation in a free-standing structure in the middle of the gallery. The piece is about the vulnerability and precarity inherent in queer-female masculinity, channelled through a video presentation documenting the outcome of a process of four strangers learning how to sing together.

However, her words could also be referencing any of the projects she has created over the course of her career.

“All of my work involves multiple people. There’s always a sense of community or collectivity,” Clarke notes, but she adds, “It’s always easier to do a hard thing with other people.”

Beyond the collaborative work with the other participants, which involved weeks of voice lessons with a vocal coach and choreographer before coming together to record their individual renditions into a collaborative performance, there was also a tight-knit crew working with Clarke to bring it all together. This included Jordan Kawai, a fellow Ryerson University documentary media MFA alum with whom she has worked since 2015’s “Parade of Champions” and who was one of the two cinematographers for the “Quantum Choir” video installation.

“When your work is autoethnographic, you’re trying to figure out ways to communicate that. Even though it is based in my own experience, I’m not special, right? The things that I feel, it’s not only me who feels it. And we know that when a woman speaks up against sexism, or when a Black person speaks up against anti-Black racism, it’s very easy for people to go, ‘Well, I’m sorry that you think that.’

“So that’s a strategy that I use in my work. It is rooted in my own experience, but there’s lots of people who think and feel the things that I do. Including those people in my work is a way to communicate from my own experience, but to communicate it collectively and to share and express that.

“We feel these things not because we’re us; we feel them because of systemic oppressions that treat people like us in certain ways.”

Clarke took this spirit of collaboration into her role as Toronto’s second-ever Photo Laureate starting in 2019, a position given to exceptional photographers whose work highlights contemporary issues relevant to Torontonians. Her tenure was impacted by the recurring pandemic shutdowns starting in early 2020, but Clarke pivoted online like so many of us.

As part of her role as an ambassador advocating for Toronto’s visual arts and photography sector, she regularly highlighted the work of various talented photographers in the city through a dedicated Instagram account (@tophotolaureate). She also used a monthly column in the Toronto Star to speak on issues like photography ethics and to highlight photographers whose work was about subjects ranging from the environment, to dissecting the male gaze, to queerness through a lens, to critical commentary on residential school photography. She even humorously addressed the phenomenon of pandemic-era haircut selfies—from those self-inflicted at home, to peoples’ first haircuts after months of lockdowns in Ontario.

Clarke held the role for three years, culminating in her first curated exhibition, “We Buy Gold,” an exploration of visual representations of queerness by emerging artists. Despite being offered an additional year to do an ArtworxTO project, since the bulk of her tenure coincided with the pandemic, Clarke came to realize that she had said what she wanted to say in the position, and it was time to move on.

“I was supposed to do a project for ArtworxTO, a free family-portrait project this summer,” says Clarke. “When I said yes, a year ago, I had no idea that a year later we would still be this deep into the pandemic. Rather than hanging on and trying to force something, I realized I needed to come to a place of acceptance and letting go of my term. I did what I could do. It’s time to hand it on to somebody else.”

Reflecting on her time in the role, Clarke looks back at a personal history of service to the community, with family members in medicine and in community-based volunteer work.

“I think photographers have felt a sense of community and a sense of support from me,” she says. “My priority has been not to shine a light on my own work, but on other photographers through the monthly column in the Toronto Star and Instagram account, because I wasn’t able to do a large public-facing project.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—this collaborative nature, Clarke’s work has always been deeply personal, and she is very candid about the fact that grief, and queer grief in particular, is a big part of her thematic focus.

“All of my work is about grief and loss. It’s always about pain. But more and more I’m very mindful and conscious of not wanting to foreground that pain—wanting to acknowledge it, while also not having it define who we are to ourselves.”

In “Parade of Champions”, Clarke drew from her own experience of losing her mother (with whom she was very close) in 2011, to explore through still-video portraits and audio interviews, the grief of three Black, queer people who had lost their mothers. With grief being treated as a private, inconvenient matter by much of society, coupled with so much of queerness being about invisibility, this installation presented a counter-narrative by allowing viewers to bear witness to Black, queer grief.

In 2018’s “Suck Teeth Compositions (After Rashaad Newsome),” Clarke features video portraits of several subjects performing the Black diaspora’s universal vocalisation of displeasure, the “suck teeth” of the title. The work served as a response to the frustration and anger at anti-Blackness in Canada being ignored or overlooked because of the dominance of African-American experiences, coupled with the prevailing historical narrative for white Canadians that, “that sort of thing only happens over there,” in the US.

However, Clarke is clear that while her work explores difficult themes within the intersections of living in a marginalized identity, the pain is not the point.

However, Clarke is clear that while her work explores difficult themes within the intersections of living in a marginalized identity, the pain is not the point.

“The work is very earnest, we are all very vulnerable, but there’s also a lot of play and humour in it, too. As hard as this thing was for us, we had a lot of fun doing it, you know?” she says of “Quantum Choir,” where she and the other three participants bonded over the vocal practice and cheered each other on during the recording of the song.

“Similarly, as hard as it is sometimes to be masculine and female-bodied, we have a lot of fun with that. It’s trying to equate these two things—having the beauty and the grace and the pleasure that we feel as who we are to be foregrounded, as opposed to, ‘Oh poor us, we have these (tough) life experiences.’”

As she notes, there is no distinct presence in pop culture of masculine-coded women, and there isn’t the same cohesiveness seen in other marginalized communities. Unless people have these folks in their own lives, there is a certain opacity about their lived experiences.

“Experiences of queer, masculine folks are not universal,” Clarke says. “But most people have shame about their singing voice—that definitely is a universal thing. I wanted to use something that I thought most people can relate to … [I wanted them to think,] this artist is asking me to equate that to how hard it is to be queer and masculine.”

For “Quantum Choir,” images of the four singers are displayed within a structural frame in the centre of the gallery, on four screens that enclose the viewer. The layout encourages an active engagement with the work. Clarke says the intention is to fully utilize the three-dimensional space of the gallery by changing up the way the audience interacts with moving-image work.

“Too often you walk into the gallery and there’s this projected feature-length film on a wall. I’m thinking, ‘Why is this in a gallery and not in the cinema?’ That dynamic doesn’t make sense to me,” she says.

“With the four monitors, even though all of us are always on screen, you can never look at all four of us. You have to make choices around who you’re looking at, which way you’re looking and when. It’s not just coming at you; you have to contend and negotiate and navigate and make your own choices. Every viewer will have their own experience of the exhibition.”

Also included in this installation are rows of soccer balls in neat configurations around the gallery and piled in the corners. At first glance they may seem out of place, but they speak to the very particular experience of navigating life as a masculine, female-bodied person.

“For all four of us, sport is the only place where our masculinity has been supported,” Clarke says of the soccer balls in the installation. The second part, “The Animal Seems to Be Moving,” engages with the tension of being extra aware of oneself in public spaces. Clarke is deeply familiar with the ambiguity that people perceive in her, and the ways their responses affect how she walks through the world.

“I’ve always been read as younger than I am. But I have found over the last few years that I’m moving from being read as a young, Black boy to a middle-aged, Black man as I age. And even though Black boys have their innocence robbed, and often are perceived to be older than they are, a Black man is still more threatening to some people than a Black boy.

“The project is reflecting on what it means to have to worry about more risk and less safety for myself in the world as I age because of other people’s perceptions of who I am and what that means to them.”

With the ongoing debate about trans bathroom access, there are people like Clarke who are not trans, but exist in a decidedly masculine body, and so also end up bearing the brunt of people’s misperceptions.

“When I walk into a public women’s washroom, it’s stressful as hell, you know? Horrible. You see women shrink in fear, and it’s horrible, knowing that you can make people feel that way. Because of their assumptions about who you are.” The absurdity of the situation—Clarke would never harm anyone—makes her reflect on coping strategies for herself and others.

For Clarke, making the work for this exhibit was as much about confronting and naming her pain as it is about diffusing it through humour and addressing the inherent absurdity in the experience.

“Humour is a long-lasting strategy of marginalized communities. With the self-portrait series, it’s not my body that’s absurd. What is absurd is the gaze and the assumptions and the ideas attached to my body.”

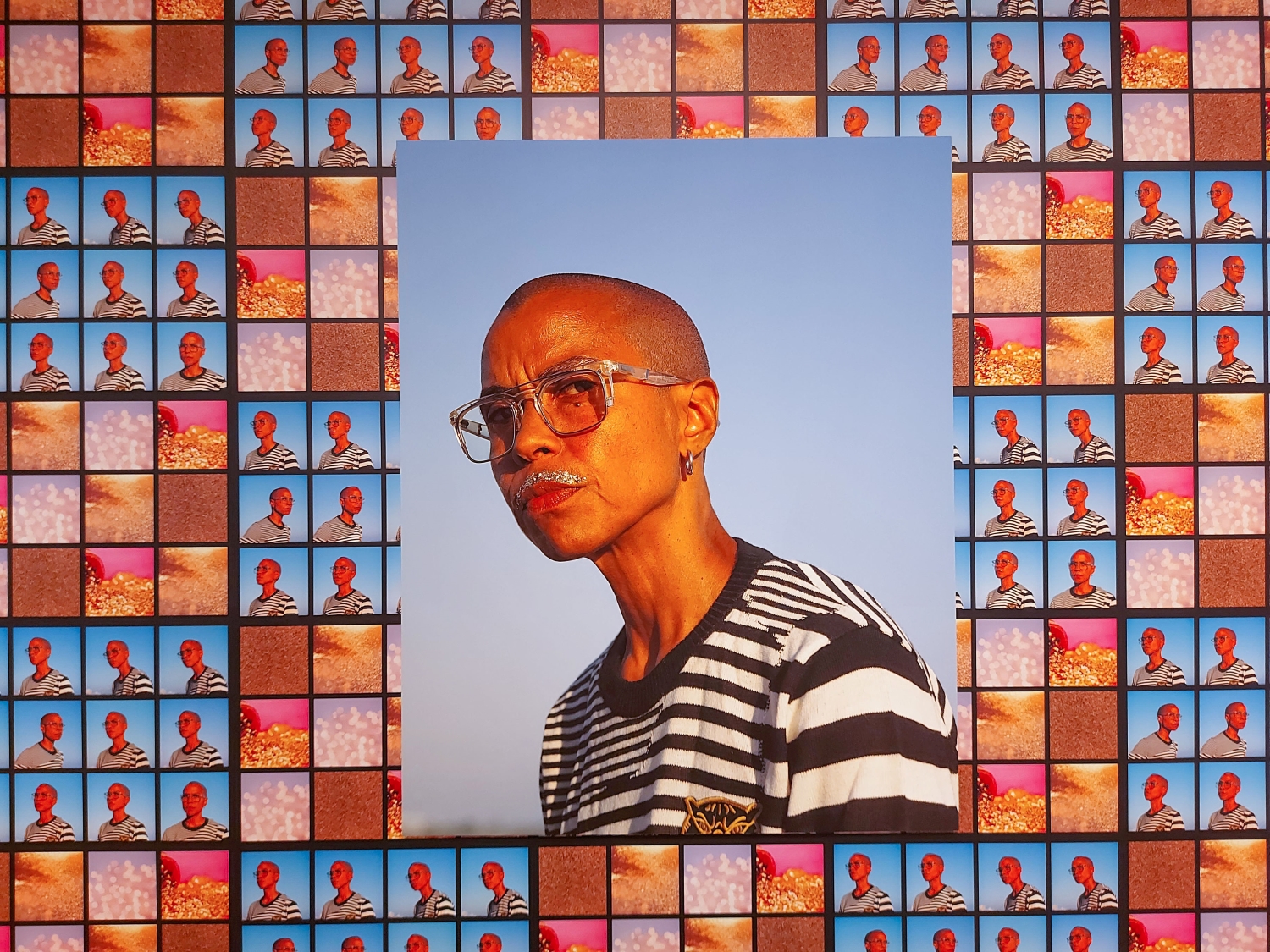

There definitely is a distinct element of play, of humour, and of performance inherent in the selected pieces in the photo gallery, despite the heaviness that inspired its creation. There is also a vibrancy to the images that speaks to a delight in existing in the body that Clarke lives in. This is especially evident in the floor-to-ceiling wallpaper featuring repeating squares of scanned negatives of her self-portrait, alternating with squares of glitter, and all culminating in a large, central portrait in the middle of the wall, where Clarke’s solemn gaze at the viewer is disrupted by the presence of a brilliant glitter moustache.

“I’m enjoying aging, so, in making these self-portraits, I want people to look at them and ask, ‘What the fuck is she doing?’ When Jordan and I were out making them, we were giggling. When I look at myself with a glitter moustache, it makes me giggle. The humour’s meant to be foregrounded. And in the end, it’s not asking people to see me as ridiculous. It’s asking people to see how people see me as ridiculous.”

Clarke hopes that with the two projects, a window is opened into the lived experiences of queer, masculine people in female bodies, and specifically Black, queer, masculine folks. For her, this exhibit speaks to multiple audiences who may relate on various levels, but her priority is specifically queer people and Black people.

“I know what it’s like when I see artwork or when I read a theory that helps me frame and concretize something that I already know to be true. Many of the things that I’m exploring, and I’m not trying to brag, are not written down. They’re not talked about, they’re not general knowledge,” she says. “We know them but nobody names it for us. And some of what I’m trying to do is to name some of these things for us.”

Speaking to this deeply personal, specific experience in a space like the Art Gallery of Hamilton is significant to the work itself. “If you have something on the wall in a gallery, there’s an automatic elevation. The gallery is a space of privilege, worthy of cultural consideration.” What Clarke is making is contemporary art and it is properly considered to be so.

In the end, Clarke believes that the work will resonate regardless of how the audience identifies. “I think everybody can relate to overcoming a personal challenge. And in the end, that’s what the work is, right? We’ve all tackled hard things in our life and we all know the freedom that lies on the other side.”