There’s never been a more robust public conversation around artificial intelligence and ethics than since late summer 2022, when a small handful of tech companies released the first proprietary text-to-image AI art generators to the general public.

For the unfamiliar, the growing field of AI art refers to machine learning platforms trained on vast amounts of text and visual data scraped from the Internet, which, when combined with text-to-image technology, allow users to describe any scene at all in natural language (human as opposed to computer programming languages) and have it output any number of fantastical images based on the text prompt. As PCWorld describes the process, it “takes user-generated queries, runs them through an AI algorithm, and lets the algorithm pull from its source images and apply various artistic techniques to the resulting image.”

The biggest early flashpoint in the debate occurred when the Lensa app gave everyone with a smartphone and a selfie camera the ability to create otherworldly profile pics of themselves (called “magic avatars”) in a vast array of painterly artistic styles reminiscent of popular artists both historical and living. This created a rapid explosion in usage, followed by an even swifter backlash for reasons ranging from the perceived devaluation of human artists’ skills to questions concerning the murky online sources for the massive image database the algorithm was trained on.

The fact of AI already being a part of everyday life aside, the emergence and swift evolution of specific technology that allows people to create visuals in seconds using text prompts has generated a huge and contentious debate in the art world and creative industries. Many of its detractors call it a job killer for human artists, while supporters herald it as the most revolutionary thing to happen to visual media since the invention of photography.

What does this have to do with documentaries? Well, of the many questionable uses of AI, one of the more concerning is the creation of deepfakes.

A deepfake—the name a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake”— is an image, video, or audio file that has been manipulated, using AI deep learning algorithms, to look or sound like something or someone it is not.

Back in 2020, The Guardian called it “The 21st century’s answer to Photoshopping” and referenced a video PSA about deepfakes that was itself a deepfake of former US President Barack Obama made by comedian and horror filmmaker Jordan Peele, who played Obama in several Key & Peele sketch comedy bits.

Deepfakes use sophisticated techniques such as face-swapping, voice synthesis, and image generation to create realistic media, either from scratch or based on existing content, that can appear indistinguishable from the real thing.

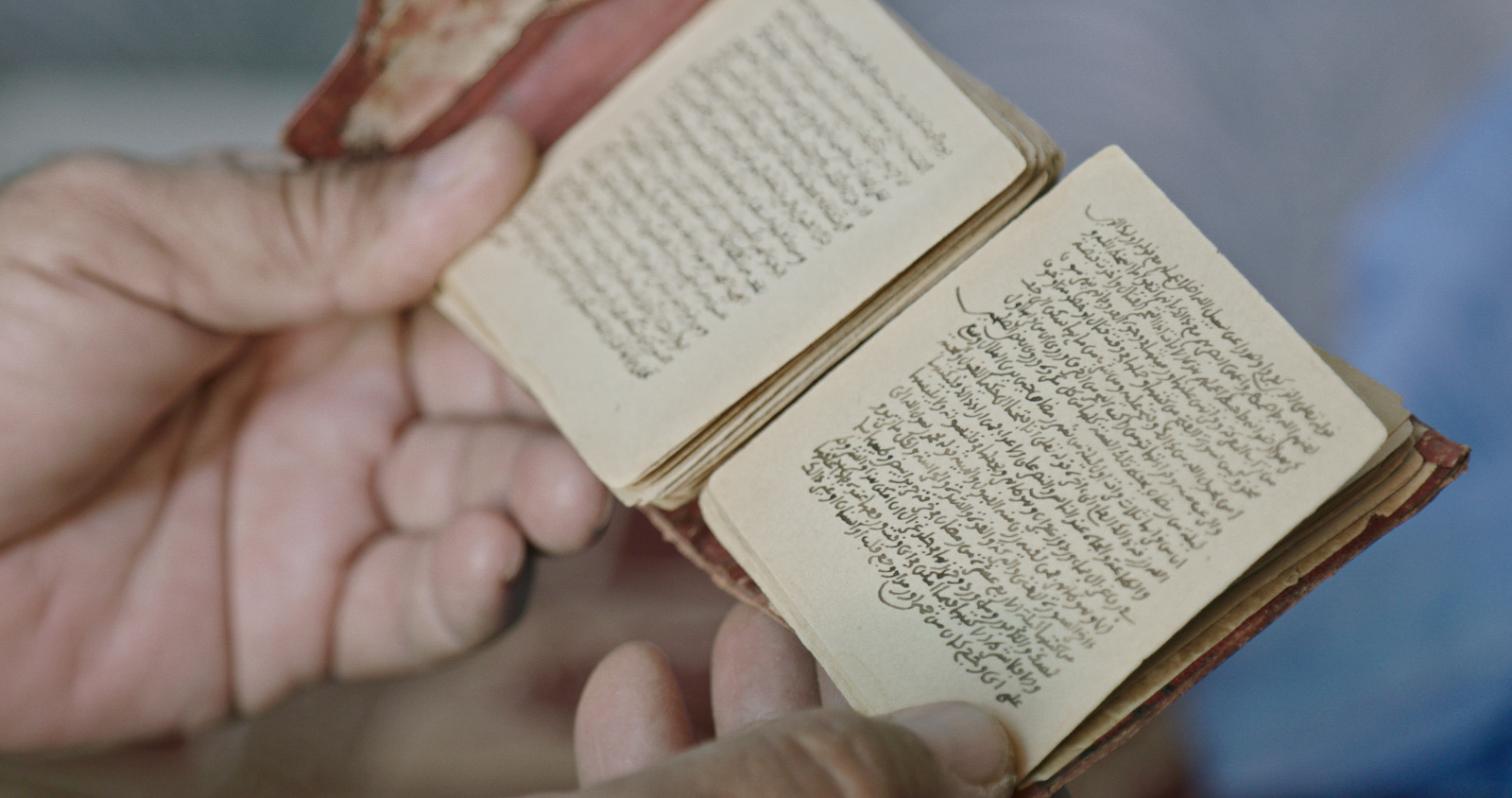

Documentary as a genre is no stranger to cinematic fakery, often employed for the sake of constructing a cohesive narrative in order to convey a greater truth. The use of re-enactments is a set-in-stone doc technique frequently used alongside talking head interviews, especially when footage of the events in question is unobtainable for any given reason.

In fact, documentary can even be self-reflexive in this regard, such as the brilliant subversion of the trope by Clio Barnard, with the late reveal in her film The Arbor (2010) that the people assumed to be her interview subjects up until this point were actually actors lip-synching to audio recordings.

But in the last few years, we have seen a number of filmmakers play with the extended possibilities of artificial intelligence, particularly by using deepfake techniques to “recreate” the voices of film subjects who are no longer alive.

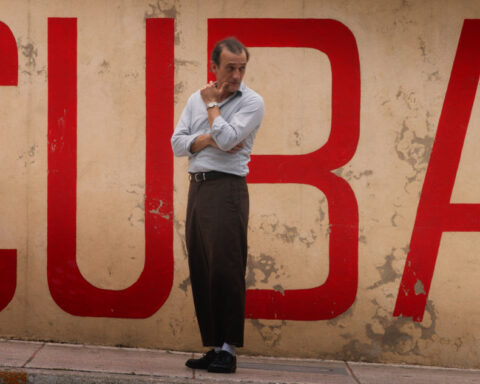

Morgan Neville in Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain (2021) used AI audio technology to have the voice of Anthony Bourdain “narrate” an email he’d written while alive, which caused controversy. The Netflix docuseries The Andy Warhol Diaries (2022) uses similar techniques in order to have Warhol “narrate” (or “Warhol” narrate) the series. The promo for the Netflix project prudently points out the approval and support of the Andy Warhol Foundation in making this creative choice, in a presumable bid to stave off negative reception from the jump.

Taking things in a different direction, Alex Gibney’s 2016 doc Zero Days, about the STUXNET virus and the political debate around cyber warfare, has as its main protagonist an anonymous but determined whistleblower providing evidence of US and Israeli intelligence networks’ culpability in unleashing the self-replicating malware in a bid to take down Iran’s nuclear program. This becomes a source of controversy when the anonymous whistleblower reveals herself at the end to be a paid actress, reading from a compilation of accounts by various sources who could not come forward themselves. While it is a very effective narrative choice, it still pulls at a loose thread in the tapestry of what defines a documentary. As such, it begins to beg the question of how a documentary can be deemed factual when it combines the use of deepfake or similar technology with questionable re-enactments or bait-and-switch interviews and strategically edited or out-of-context soundbites, especially if one is not being completely transparent about the process.

These questions are important because the use of AI in mediums from film to music, and now even writing with the emergence of ChatGPT, is only going to become more prevalent. In fact, some, if they could have it their way, would love to see AI take over every element of the creative process: A January 2023 Globe and Mail article notes that, “at a UBS Group AG technology conference in early December, the president of advertising software company Viant Technology Inc., Tim Vanderhook, said his long-term plan for ad campaigns ‘is that no humans are involved.’”

But even more important is the idea of maintaining a reliable historical record.

Had some time on my hands. So, I created these 90’s female heavy metal/goth girls that never existed, attending a 90’s heavy metal concert that never existed with an AI app. Cause you need that in your life. 🤘🏽🖤 pic.twitter.com/ElQiFwcR1O

— Fallon Fox (@FallonFox) November 13, 2022

In November 2022, a series of Polaroidesque images showing Black women metal fans at concerts during the ’90s went viral for the uncanny fact that none of the people or places depicted in the images had ever existed in real life: Each “photo” had been created using AI image generation program Midjourney by former MMA fighter-turned digital artist Fallon Fox. As a Black artist, Fox described the project as an effort to see Black women represented in a subculture loved by many of them, but which does not often love them back.

This hyper-realistic alternative vision raises the question of the integrity of the future historical record, given that apparently “documentary” images can be fabricated in this way.

Given that anyone can now create fictional historical documentary photographs in the style of, say, Gordon Parks or Dorothea Lange with near-perfect accuracy (the uncanny valley of AI image generation lies in the flawed depiction of hands and teeth), and given that the viral nature of image sharing on the Internet does not lend itself readily to fact checking, it isn’t hard to draw the conclusion that, without strong critical media skills, it will become increasingly difficult for laypeople, or even veteran media practitioners, to tell reality from “almost-real.”

@unreal_keanu Hey! My cupboard has a little message for you! #keanureeves #reeves #morning ♬ original sound Unreal Keanu Reeves

There is a TikToker, for example, whose entire channel is dedicated to being “Unreal Keanu Reeves.” He uses deepfake technology to place the actor Keanu Reeves’ face over his own, with exceptionally realistic facial expressions, while doing mundane things around his home. From the comments, many, many viewers were at least initially taken in by the accuracy of the depiction, unaware this was a parody account of sorts, despite it clearly labelling itself “Unreal Keanu.”

And then, of course, there are the humorous—if unsettling—YouTube clips of talk show guests being real-time morphed into other people while they speak, or old film trailers being re-edited with different actors, new faces and voices being swapped in for the originals.

The companies behind Dall-E, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney, the three major AI art generators released last summer, have all made statements describing the safeguards they have attempted to put in place to prevent community misuse in the form of lewd or demeaning representations of celebrities or even people users might know personally. Up until recently, users could not upload images of real people to Midjourney or Stable Diffusion as source imagery for art generation to prevent this very type of abuse. That they now allow this is explained as the result of a more robust content moderation system, but that remains to be seen.

But, one needs to ask, what are the companies that are marketing these services, and who is behind them? What are their business and funding models? And, perhaps most importantly, what are their ultimate goals?

Stability AI is the company behind Stable Diffusion. This is one of the more popular AI art platforms because of its open-source nature (the tagline on the company website reads, “AI by the people for the people—We are building the foundation to activate humanity’s potential”) as well as the ability for its source codes and training models to be downloaded and used by any consumer with a reasonably powerful computer, such as a gaming PC. This is in contrast to the proprietary, cloud-based nature of the others. Lensa, the above-mentioned AI app for creating “magic avatars,” is one of several new AI art apps built on Stable Diffusion’s source code, a fact the company is proud to point out.

In July 2022, PCWorld described Midjourney (which had just been opened to the public in full beta mode and is thought to be based on Stable Diffusion’s underlying technology) as “an enthralling art generator,” and “one of the more evocative platforms for AI art.” Midjourney describes itself as, “an independent research lab exploring new mediums of thought and expanding the imaginative powers of the human species” and “a small self-funded team focused on design, human infrastructure, and AI.” Among its advisors are heavy hitters such as Nat Friedman, CEO of GitHub, Jim Keller, “Lead Silicon at Apple, AMD, Tesla and Intel,” and, interestingly enough, Bill Warner, founder of Avid Technology and the inventor of non-linear editing.

And then there is DALL-E, created by the company OpenAI, which PCWorld referred to as “the grandfather of AI art generators.” The very first text-to-image AI art program, the name is a combination of Dalí, the Spanish surrealist master, and WALL-E, the 2008 Pixar film about a solitary robot abandoned on an uninhabitable Earth to clean up humanity’s messes. OpenAI is an American AI research lab that runs on the fifth most powerful supercomputer in the world, and was founded (and funded) by a deep-pocketed group of tech founders including Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Jessica Livingston, and Sam Altman, along with Canadian computer scientist and deep learning expert Ilya Sutskever. OpenAI has been fairly vocal about its goal of “building a friendly AI,” and this, alongside variously stated ideals about realizing humanity’s potential through artificial intelligence, seems to be the prevailing goal of each of these companies.

But unsurprisingly, while the AI debate has been raging, news from further afield confirms that behind every smoothly functioning automatic Internet experience is an underpaid and overworked contract worker manually sifting through the worst of the Internet to present the best of it to users. The content moderation company Sama, with contract staff based in Kenya, was recently the subject of a Time exposé after being sued over poor labour practices and union-busting, and for failing to provide sufficient mental health support, let alone a living wage, to its African staff. For under USD $2/hour, roughly the wage of a receptionist in Nairobi, the staffers’ jobs involved reviewing graphic online content for Meta, Facebook’s parent company, and filtering vile hate speech to help train OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Meanwhile, iRobot, makers of the Roomba automatic vacuum cleaner, came under fire recently when it emerged that the tester models of its latest iterations, which use cameras instead of sensors, had been taking sensitive photos from within people’s homes and uploading them to a database where household objects were to be labelled to better train the vacuums’ onboard computers. The problem is, the people who signed up as testers were not told that this labelling would be done manually by humans, who might upload some of the more remarkable images they receive to the Internet. Which, of course, happened.

On the other hand, AI techniques have also been used in various ways by documentary filmmakers as an ethical way to protect vulnerable sources and interview subjects. David France’s film Welcome to Chechnya (2020) uses AI to obscure subjects’ identities for safety reasons. This recalls films like Joshua Oppenheimer’s masterpiece The Act of Killing (2012), which had an entire credits list worth of “Anonymous” Indonesian cast and crew to prevent retribution against them or their families after the film was released. Using AI seems like a natural extension of this impulse, but this time on steroids.

Documentary as a genre has had an ironclad reputation for being a credible source for accurate, fact-checked, deeply researched storytelling. Up to now.

Like all revolutionary human inventions, this sword has a double edge. What kinds of shifts will need to take place in reality-based media in order to preserve the credibility that comes from telling a story as close to the objective truth as possible, with the raw footage or back-up data to prove it, while also embracing and redefining the capabilities of the genre as technology continues to evolve?

Since Trump’s ascendance to the US presidency in 2016, the term “fake news” has become ubiquitous, often used by online commentators to counter arguments with which they don’t personally agree. How much more widespread might that doubting, closed-off attitude become as audiences start to question the true source of the images being sold to them on screen? Documentary as a genre has had an ironclad reputation for being a credible source for accurate, fact-checked, deeply researched storytelling. Up to now.

There could be a shift coming where we in the doc world will have to clearly define the lines between re-enactment and wholesale fabrication.

I don’t have an answer about what is to be done, but I am convinced that these are the questions that we need to be asking. I suspect that the documentary world will need to lead the charge in terms of defining ethical solutions to these issues, without waiting for the rest of the world to catch up.