When you break it down, 1971 truly was a watershed year for popular music. Coming after the experimentation of the years prior and the massive social and political changes that affected the entire world, the beginning of the 1970s proved to be one of the most creatively and culturally explosive twelve months of the modern era. So much of what we consider classic today – from rock, folk, soul, funk, R&B, dance, modern symphonic, and even nascent hip-hop – grew from this fertile era.

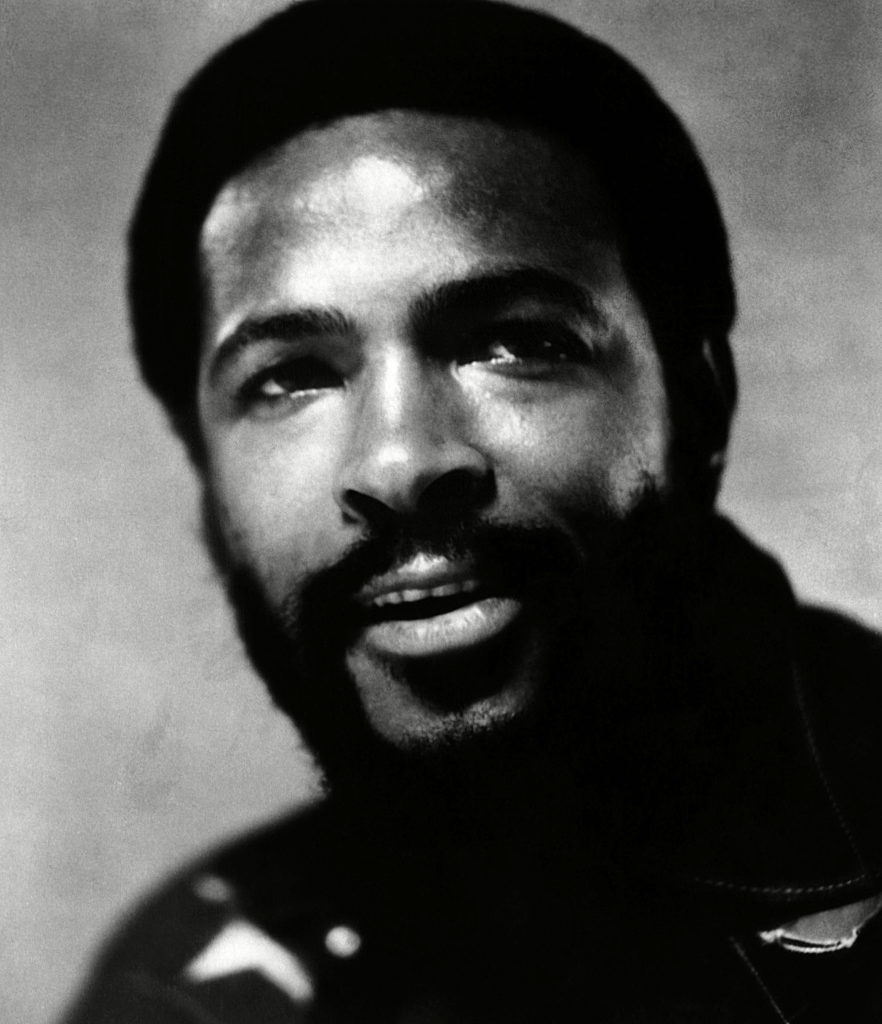

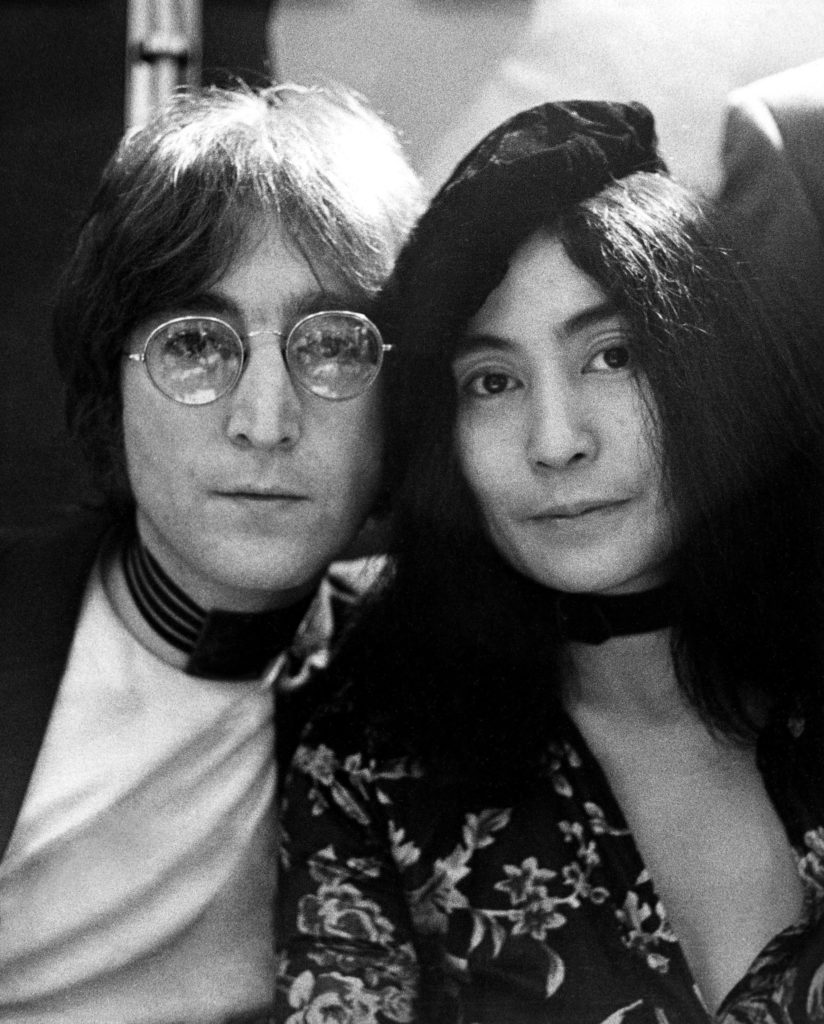

Based in part on David Hepworth’s exhaustive look at the period, Never A Dull Moment: 1971 The Year that Rock Exploded, the documentary provides an engaging overview of the musical landscape of the period. Focusing on key characters who rose the decade before like Marvin Gaye, John Lennon, Ike & Tina Turner, The Staple Singers and Sly Stone, along with newly minted talents like David Bowie and Elton John who would dominate the next ten years. The eight episode series dives as deeply into the political circumstances of the day as any of the music did. 1971: The Year that Music Changed Everything uses the same formula as seen in executive producer Asif Kapadia’s films like Amy (2015) and Senna (2011) in which vintage footage is buttressed by contemporary voice-over interviews. Visually, the film keeps its scope to the era under discussion while offering the testimony of those who witnessed these events and are looking back with the benefit of time.

POV had the pleasure of speaking with two leading contributors of 1971. James Gay-Rees is a producer and writer who has long collaborated with Kapadia, including the Oscar-winning Amy and the remarkable F1 documentary Senna. James Rogan is a producer and director of a number of documentaries and TV-mini series.

POV spoke to the pair via Zoom from their location in London, UK.

POV: Jason Gorber

JGR: James Gay-Rees

JR: James Rogan

The following has been edited for clarity and concision.

POV: Given the sea of choices from such an epic period in popular music, what did you know going in that you had to tackle, and what did you know you would not have room for in the scope of the film?

JGR: When you have such an embarrassment of riches, what do you not use? Even with an eight-episode show, you’re going to be scratching the surface. Obviously there’s a temptation to just go with the well-known music and not diversify too much. The series is based on a book called Never a Dull Moment by David Hepworth, which sets out the year chronologically in terms of the releases. Although that’s a very compelling read, we decided to move away from that structure as we started to research. The obvious trigger point was about how can all of that amazing music come out in one year? There’s just too much classic music from 1971 that we listen to today. What the hell was going on? As we investigated the machinations of that year, we realized there were key themes that emerged. It then became a question of working out which music fit those themes. Some of the tracks were very obvious and very direct, while others were far less obvious. We weren’t just focusing on white rock music and wanted to touch all four corners of the musical landscape. All different types of artists were knocking it out of the park during this era, so we wanted to get that balance. All this helped it become organic and evolving structure.

POV: How much of final selection was driven by footage you had access to, versus topics that may not have as rich an archive of visual material to draw upon?

JR: We had a couple of organizing principles. When the music clearly interacted with the politics or the culture of the time and there was footage of that, then that was something we would obviously look at. That put Lennon and the Imagine documentary footage in a central space. Beyond that, it’s actually a case of saying what is it we’re trying to say, and how many of these events will build up the narrative, in order to give an accurate feeling of the time. We look at Marvin Gaye, and with him there wasn’t a lot of archival footage to draw upon. Yet What’s Going On? was just a towering album of that year, and trying to understand its impact was absolutely always going to be essential. The last bit is personal preference. There were moments where I would hear a track, or be reminded that a track had been written in 1971, and I’d fight to have that in one of my films. I saw the performance of Tina Turner singing “Proud Mary” in Paris at the beginning of 1971 and it’s just absolutely mind-blowing. Her performance singing “I Smell Trouble” in Ghana [from the Soul to Soul documentary] was even more powerful. There were elements we had to have because they’re just so amazing at the performance level, and others because they were just so impactful at a political and cultural level.

POV: Who is this show for? If it’s for the person who is obsessive about this era of music, there’s all kinds of things in here that are frustrating about what’s left out or glossed over. If it’s for somebody who doesn’t know that they should care about this era, is it meant to serve as an introduction? Or is it for the generalist who already has a vested interest but wants a more in-depth yet soothingly nostalgic look back at this era?

JGR: If you look back at a film like Amy, the film we made about Amy Winehouse, that’s not strictly designed for those who were already fans of her. Our ultimate ambition was that audiences were going to come away from this film affected by it, even if you don’t like her, because it’s saying something to you about the human condition. I think that always has to apply in everything we do.

We don’t just make it for the core audience, because that’s going to narrow your perspective too much. You have to try to make the films or the TV shows as accessible to as many people as possible without dumbing them down. That obviously was the challenge in trying to find that balance. We always tried to elevate these things, so that people who don’t even like rock music, or don’t even like Motown, or don’t even like Marvin Gaye will say, “In this context I get it, and I see where it was coming from.” They may still not like it, but they may appreciate what went into it and why it was made at that time.

I have a 20-year old daughter and she listens to hip-hop and drum and bass all of the time. She knows all of this 1971-era music because this has been the soundtrack to our collective backgrounds for so long. When I showed her some of the episodes it was gratifying to see somebody from her generation understand what was behind this or that record now, and what that record was in response to. I don’t think 1971 is going to be limited to men and women of a certain age who were either around at that time or are naturally drawn to that type of music from that era. I think it can potentially play to as wide an audience as possible because the message behind some of the music is as resonant today as it was then.

POV: The film overtly sets itself in 1971, yet you spend a great deal of time with recordings made earlier that came out that year, or other records that were recorded during this timeline but released afterwards. It’s easy to get pedantic about what constitutes a 1971 musical event, so could you talk about the choices to focus on these titles versus sticking more closely to that 12 month period of release?

JR: We talked endlessly about which artists we were including and not including. We had huge debates, not quite to the point of tears, but there were some things that were heart wrenching that we couldn’t include because we couldn’t include for rights reasons. Then there were some things that just ended up falling out of the edits just for time reasons. We talked about the very question of what is a ’71 track. The “What’s Going On” single is released in January ’71 but it’s recorded in June 1970, and then the album is recorded in March ’71, and its zenith of impact was probably around May of ’71. Our overall rule was very simple: If the music is making waves in ’71, or is being made in ’71, then it’s part of the story we’re telling. Our story was what were the artists doing, as evidenced by John Lennon responding to the “What’s Going On” release.

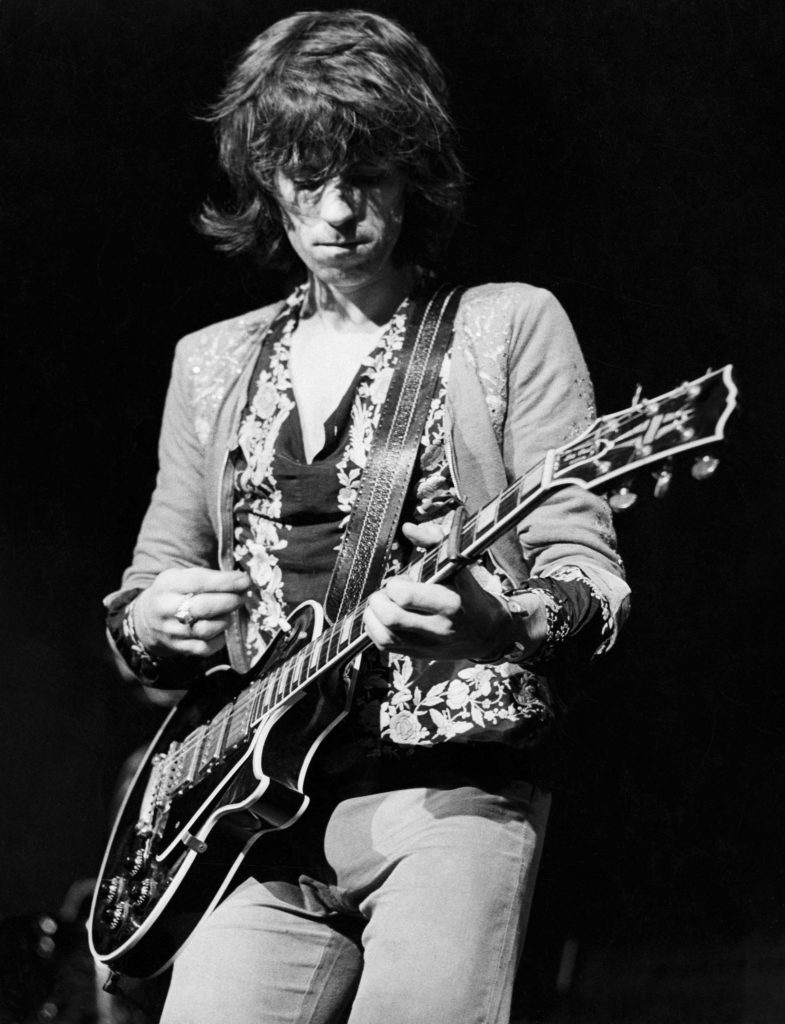

POV: Just to push back, then, why isn’t this entirely about the Stones’ “Sticky Fingers” instead of them recording “Exile on Main Street”? Is it simply because we have Cocksucker Blues footage to draw upon? You spend two episodes about the making of a record that came out and had all its impact in 1972.

JR: I did not direct that episode. But I can definitely say that, for instance with The Staple Singers, “I’ll Take you There” was written and recorded in October ’71. Al Bell told us the story of how he wrote it after going to the funeral of his brother of that year. That’s the same theory that can be applied to “Exile on Main Street.” The band was in free fall. “Sticky Fingers” had actually been recorded March 1970 so it had been a long time coming. By the time the Rolling Stones were actually picking up and playing on their guitars in 1971, it was for the recording of “Exile.” So the question it, what was vital to these musicians at this moment? All of that is to say, we’re looking forward to debating about which records didn’t get to put in for years to come.

POV: [Obnoxiously points slowly to copy of record in background of Zoom shot]

JR: Ah, yeah, Aqualung! Anyway, that’s going to be part of the joy of this series, this sense that when music lovers come to it that there’s going to be some massive treats, but also going to be some moments of “Where the hell is Zeppelin IV?!” That kind of sense of energy and commitment to the music of the era is part of the reason why the series was made.

POV: It’s traditional in British documentaries to shit on prog music of the era, with the usual trope that everything was garbage until punk saved rock and roll. You do have a very brief moment of Yes, but quickly use them as the antithesis of music being made by likes of T-Rex.

JR: We’ve gotta talk about Bilotti! James Bilotti is one of the producers of 1971 and he’s a die-hard prog fan. This conversation was had over and over and over again. I’m not quite sure – do you think we shit on prog music in our show?

POV: A little bit? We can discuss this one day over a pint! Last question for Mr. Gay-Rees, when you’re dealing with something like music and politics, how do you coalesce it into a film and make sure that it works for everybody but still works on its own without being superficial?

JGR: I haven’t got long enough to fully explain it, but it’s a very long, time consuming process. You have a thesis, and you stress test that thesis. You realize there are holes in it and therefore you have to basically continue reinventing the thesis so that, firstly, it’s legitimate and we don’t get hammered by journalists like yourself. It’s just a question of trying to make sense of the music in the situation. To answer your earlier question, you can’t make another series based in another year in music, because the premise here is that this is the greatest year in the history of rock and pop music …

POV: [polite interruption] Sorry, I meant, would you consider doing another eight episodes about 1971.

JGR: We totally could! I don’t know whether we’d be able to, but we left it wanting to do more. There was an embarrassment of riches left to discuss. If our series even starts people on the journey towards listening to it all, then it’s done its job.

1971: The Year that Music Changed Everything is now streaming on AppleTV+.