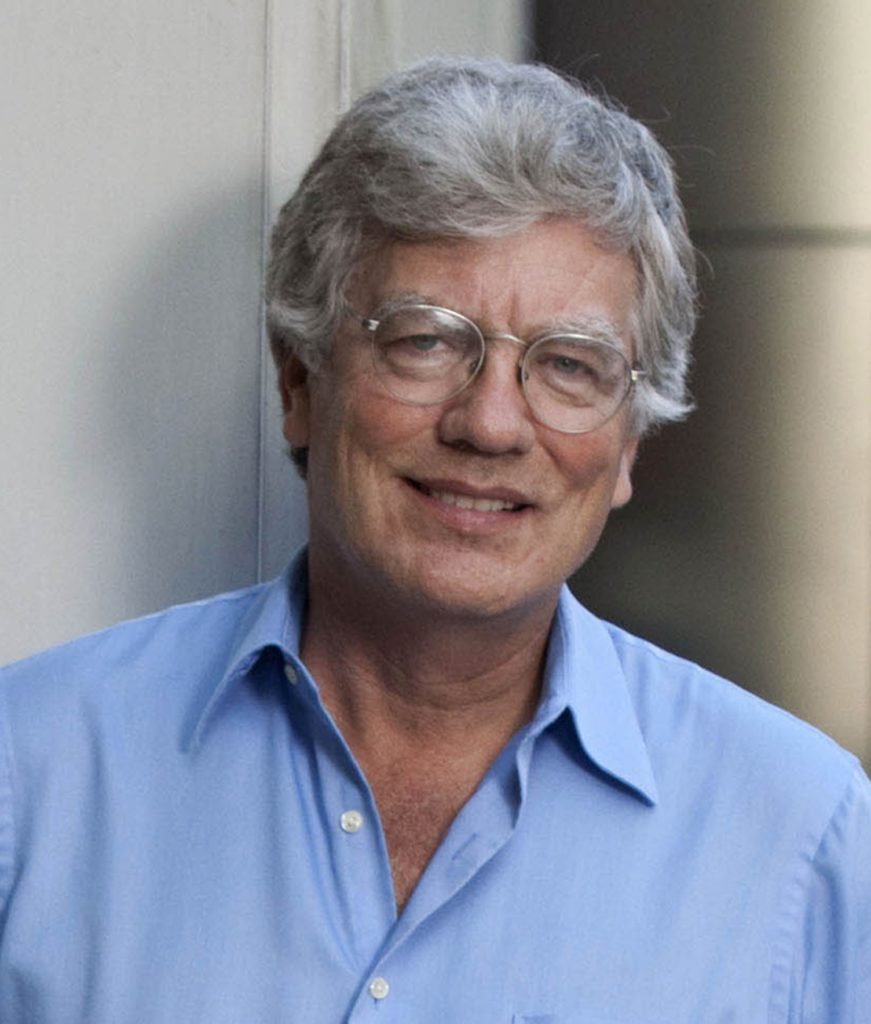

Peter Raymont is a central figure in the development of an independent documentary movement in Canada. Hired by the NFB shortly after graduating Queen’s University, Raymont worked variously as a director, producer and editor throughout the Seventies, concentrating on Canada’s political process (Flora: Scenes from a Leadership Convention) and the territory now known as Nunavut (Sikusilarmiut, Whale Hunting). In 1979, he drove from Montreal to Toronto and started his own company, which quickly evolved into White Pine Pictures. Along with Rudy Buttignol, David Springbett, John Walker, Geoff Bowie and several others, Raymont was involved with the creation of DOC (Documentary Organization of Canada), which was first known as the Canadian Independent Film Caucus. The early years of Raymont’s remarkable career are covered in an interview I conducted with him for POV in 2006, which ended with a discussion of his acclaimed film Shake Hand with the Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire (2004). This interview continues Peter Raymont’s filmic journey. — Marc Glassman

POV: Marc Glassman

Peter: Peter Raymont

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: Peter, let’s start our interview again, after all these years, with A Promise to the Dead: The Exile Journey of Ariel Dorfman (2007).

Peter Bregg Images

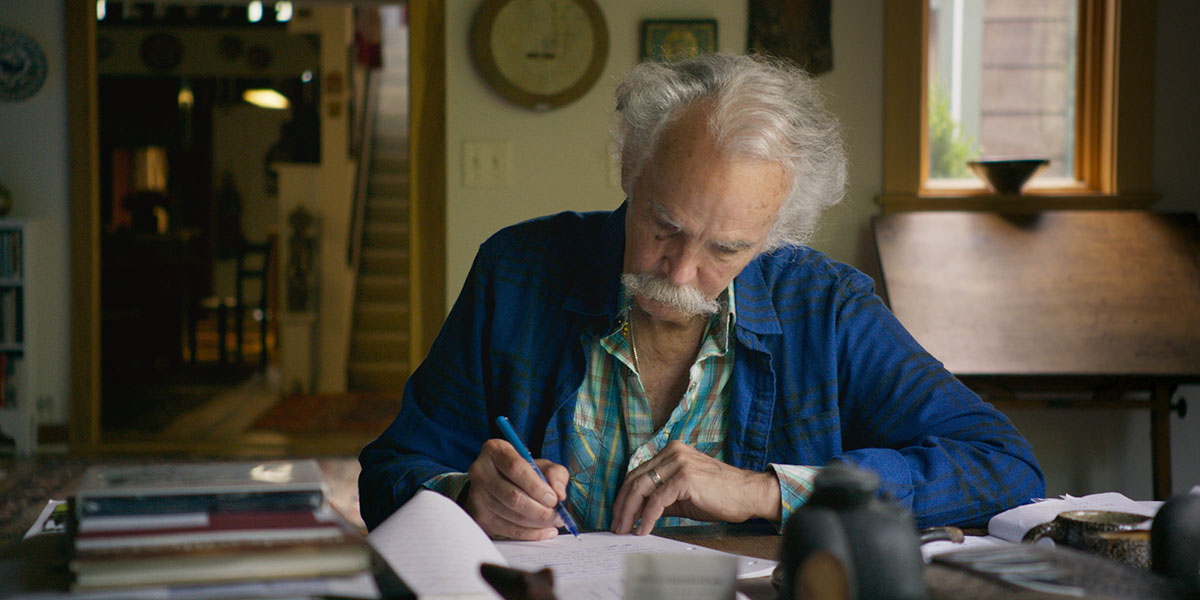

Peter: I met Ariel at the Full Frame film festival in North Carolina, where he teaches at Duke University. I was showing Shake Hands with the Devil, and he moderated a panel I was on called “Artists in a Time of War.” He started by reading a poem that he’d written on the occasion of moderating the panel. He is an extraordinary person. I was sort of intimidated by Ariel but I really liked him a lot, so when I was leaving the festival, I went up to him and said “Look, if you’re ever planning on going back to Chile“—because he was Salvador Allende’s cultural advisor during his revolutionary regime—“I’d love to go with you and maybe we could make a film.”

I’d just had the experience of filming Roméo Dallaire going back to Rwanda during the tenth anniversary of the genocide, so I thought that if Ariel was going back to Chile on some sort of occasion—for the anniversary of Allende’s death or something, there could be the basis for a good film. Ariel started sending me things he’d written and I started sending him my films. We had this sort of pen pal relationship via the internet and we were getting along really well. I even filmed him a bit in New York at a play of his that was opening. Then Lindalee (Tracey, Peter’s wife and film partner) started getting really sick. I was living with her in her hospital room, in the palliative care unit of Princess Margaret Hospital. I had a little cot beside her bed and my laptop. You visited.

POV: I did. I remember this very well.

Peter: So many people visited. It was lovely, in a way. I’d wake up every morning and make sure Lindalee was comfortable and had what she needed, and then I’d check my emails and there would be something from Ariel Dorfman. He would send a poem every morning—either a poem he’d written that day, just for us, or he’d send us a poem by Rumi, the Persian poet—and I would read these to Lindalee. It was lovely, Ariel communicating with us that way. After she passed, Ariel said “Look, Peter, I’ve got to go back to Chile, but it will be soon, in two months.”

Lindalee passed away in the middle of October and he was going in December. I wasn’t in any shape to go anywhere. I tried to get another couple of people to make the film, because I just didn’t feel like I could. Caring for someone who is dying is really, really hard. Eventually, though, I couldn’t really find or think of anyone else, so I just went and did it. It was hard because there were times when I was just not there, not present—my mind was just on another planet. But in the end, it was probably helpful. It got me back in the world, and I couldn’t be back in the world with a nicer guy than Ariel Dorfman and the beautiful place that Chile is. So we made a good film, and we just happened to be there when Pinochet died. [General Augusto Pinochet was the leader in the American financed right-wing coup that overthrew the democratically elected presidency of socialist Salvador Allende in 1973. Allende died as did many of his key advisers but with “a promise to the dead” to always keep their memories alive, Dorfman went into exile.]

POV: You did! Documentary luck.

Peter: Yeah. So that forms an important chapter near the end of the film—the death of Pinochet.

POV: I like the idea that you were able to put in a complex political situation in the story. You were able to show that Pinochet was actually beloved by many Chileans. That must have been a choice, given what was going on at that time.

Peter: We were standing outside the hospital with all these mourners of Pinochet—people who revered him. He’d killed thousands of people, tortured people, but there were Chileans, who didn’t want to believe any of that and just felt he was a great leader of their country. Ariel went up to one of them and tried to talk to her. It’s quite a powerful moment in the film, of him reaching out across this great divide. He loves Chile and, if Chile is to continue, the Ariel Dorfmans have to be able to communicate with the woman who loves Pinochet and vice versa. It’s the only way forward for Chile.

POV: White Pine is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. Can you talk about The Border, the company’s first TV dramatic series and Lindalee’s last project? Its success helped White Pine grow, didn’t it?

Peter: Exactly right, Lindalee was the one who started The Border (2007). She’d written a lot of magazine articles about illegal immigration and the relation between the cops and the immigrants in Toronto. She had hung out on the border in Niagara Falls and witnessed people sneaking across. She won a magazine award in 1991 for the Best National Investigative Report from the Canadian Association of Journalists, beating out the Fifth Estate and a number of very well-financed bodies. Lindalee was really into border immigration; we did a documentary series called The Undefended Border (2002), about the same thing—the immigration police.

POV: I guess it must be obvious to you, but these days, with Trump, the idea of the border seems to be even more high-profile and more problematic than ever.

Peter: Absolutely, they’re building walls.

POV:: How does it feel to you, having worked on this material ten to fifteen years ago, to reconsider it this year? It wasn’t like it was nothing then, but immigration and refugees are up there with the environment in terms of being the biggest issues today.

Peter: We were filming when Bush got elected and 9/11 happened, and they were sending all those people on what they called “rendition flights“— to be tortured. In fact, in the second season of The Border, a rendition flight lands on a road in rural Ontario—the bad guys had taken over the plane. It’s a really cool episode, which the sadly departed Dennis McGrath wrote.

Anyway, Lindalee was interested in doing a drama, and she had the instincts because she’d been an actor. We managed to get Susan Morgan at the CBC to give us some development money, and it was in development forever. Sadly, it only got funded and into casting when Lindalee was in the last months of her life. She was still there for casting, though. In fact, we would have meetings with the director of the pilot episode in a room next to hers in the palliative care ward.

POV: You took me on the set during the first year of The Border when it was being shot and it felt so different from being with people shooting documentaries. How was it for you, to be an executive producer on a drama?

Peter: I’d never been part of a drama series before. When I went to the Canadian Film Centre (CFC,) I watched the shooting of Street Legal—because, you know, we were all expected to come out the CFC and make feature films. [Laughter]. That only really happened for Holly Dale. I worried, at first, that I wouldn’t know what I was doing, but it was obvious: hire the best writers, the best directors, actors, crew. It was a great team doing that series—Brian Dennis, David Barlow, Janet MacLean. They were wonderful people who really knew what they were doing, and they could see that I was suffering and all that, so they really took the reins. I would just be a sort of visitor on the set, observing what was happening, but I think I was good in the editing room, even on the drama.

I’ve always been good in the editing room. Documentary filmmakers are shooting reality, but they’re also reconstructing reality. You’re cutting it down, chopping it up, shortening it—“Heightening it and tightening it,” as Roman Kroitor, a great NFB filmmaker used to say. In documentary, you’ve also got to make sure it still feels real, even though you’ve cut it down. It’s the same with a drama. You want it to feel real, and not phony, even though there are actors and scripts. It requires those same instincts.

POV: One thing that’s impressed me over the years is that you’ve really shown your dedication to documentary. A lot of people, when they morph into doing dramas, leave documentary behind. You didn’t do that. You took the money and put it right back into doing documentaries. Can you talk about that choice?

Peter: I remember going to Telefilm once, to have a meeting about getting money for a documentary. Peter Pearson was the head of Telefilm at that point and he said “Oh, Raymont! You’re still making documentaries.” He said it like it was a bad word, like “You’re still in kindergarten,” or something, right? I thought “No, that’s not right.” I love making documentaries and there’s nothing junior or kindergarten-esque about documentaries. They’re on the same plane as any other creative endeavour. Just because people get paid more to produce and direct features and dramas doesn’t make them better. It’s wrong, actually, that they get paid so much more. An editor of a documentary, compared to an editor of a drama series of a feature film, is paid so much less. It’s ridiculous because it’s actually much more difficult, I think, to edit a documentary, where you’re constructing sequences and conceiving a structure without a script. It’s much harder work.

POV: The documentary editor is really the story editor.

Peter: Yeah. You’re almost the director! You redirect the film all over again in the cutting room.

POV: I couldn’t agree with you more. How do you react to people who say that documentary “isn’t an artform?”

Peter: No. Of course it’s an artform. It’s an extraordinary artform. It’s only really in the last ten years that documentary features have become really popular. People my son’s age—in their twenties—will go to a film and they don’t really care if it’s a documentary or a drama. They just go to good films.

POV: Your next major documentary feature was Genius Within: the Inner Life of Glenn Gould (2009). What drew you to Gould?

Peter: I read an article in The Toronto Star about Cornelia Foss—the composer Lukas Foss’ wife—and her relationship with Glenn Gould. It was a story that had never been told before. There had been many books written about Glenn Gould, but nobody had ever written about his private life, or his love life, until Cornelia, decided to speak publicly about it for the first time. Michèle Hozer and I co-directed, and I think we did three or four interviews with Cornelia Foss by the end. Every time, she would offer a little more depth to the story. It took a while for her to really trust us. Even though she had done an interview with The Star, it’s different when you’re on camera and you know it’s going to be a feature film seen by millions of people. Her son and daughter were extraordinary—we were very proud of those interviews. For them, Glenn Gould was a sort of surrogate father for several years while their mother moved to Toronto. The idea was that she was going to get married to Glenn Gould.

POV: I’m interested in contemporary composers, and am aware that Lukas Foss has a real reputation in that field.

Peter: Oh sure. Gould was actually very impressed with Foss. He had tremendous respect for him, so it was kind of an awkward “love triangle,” as Cornelia put it. She said “It was quite normally, just a love triangle. It’s quite common, really.” [Laughter]

POV: I like that.

Peter: They’d go back on the weekends to Buffalo, where Lukas was. She’d go back with the kids and spend the weekend in Buffalo with her husband. Then she’d come back to Toronto for the week—the kids were in school in Toronto—and be with Glenn Gould.

POV: Your film was really the revelation of all that. No one had talked about that part of Gould’s life at all. It’s a strong film.

Peter: The film wasn’t just mine. I co-directed with Michèle Hozer, the great editor. I think the relationship between Michèle and I has been very important. We worked together on the Dallaire film, where her editing was crucial. She’s just so intelligent and is able to deal with the complexity of volumes of interviews and other footage. She works very instinctively.

She was a great person to collaborate with. On the Gould film, she really carried the ball and did almost all the interviews, and made a lot of the choices on the music to be used and on the archival materials we tracked down.

POV: Starting with Gould, much of your directorial work has been around artists.

Peter: That’s partly influenced by Nancy Lang, who became part of the company and a big part of my life. She’s a painter, who brings a visual sense to the films. I’d also always wanted to make a film on Tom Thomson, so she did the research and wrote the outlines for that. We worked with Michèle Hozer on West Wind: The Vision of Tom Thomson (2011).

POV: Why were you interested in Thomson?

Peter: Well I fell in love with Tom Thomson when I was a teenager, going to summer camp. I went to a camp called ‘Camp On Da Da Waks Men of the Woods‘—it was the Ottawa YMCA camp on Golden Lake, near Pembroke. We’d go on these wonderful canoe trips into Algonquin Park up the Bonnechere River, and when you were a senior camper, you’d go for two weeks. So I’d read a lot about Tom Thomson, I loved his paintings, and we’d paddled the same rivers. It sort of felt like we were camping at the same campsites as he did. He was also romantic figure, partly because he died so young—think of a life cut short and a promise unfulfilled. So it felt like a great story for a film, and fortunately, when I met Nancy, she was very interested in Tom Thomson as well and knew quite a bit about his story. We got that one going with Bravo, where Charlotte Engel was still commissioning films about artists.

POV: It was a good time. It’s too bad it ended.

Peter: Well, you know broadcasters come and go, and change and morph. One of the important skills—or essential ingredients—of being a small company, like ours, is keeping on top of all those changes. We’ve got to keep on top of changes in mandates of broadcasters and funding agencies, and in the people who are in positions of power—getting to know them, taking them out for coffee and lunch and, you know, finding out what they’re up to. You’re not always pitching a new project, but you’ve got to get a sense of their interests.

POV: Right. Now Charlotte is at the CBC, in the POV strand. You must know the majority of the documentary commissioning editors in the world.

Peter: We’re always talking to people at CBC, and at Crave, at CTV, at the Movie Network, at the Documentary Channel, at TVO, at Super Channel—and then there’s the internet. I just came back from the Sunny Side of the Doc, which is this wonderful marketplace of ideas in La Rochelle, France. There must have been fifty people from ARTe-France and ARTe-Germany, as well as people from the BBC, Channel 4, and Sky, and all the broadcasters in Europe—especially the public broadcasters. There were people from PBS and CBC there, people from South Africa and Australia. We’re, more and more, collaborating with producers in these countries too—not just directly with broadcasters. We’ll co-produce with a German, or a French, or a UK producer because they have better access to the broadcasters in their countries, and we have treaties with most of these countries too. It’s an on-going network of contacts that makes it all possible.

POV: I think of Michèle and director Patrick Reed, who made Triage (2008), Fight Like Soldiers, Dies Like Children (2012) and so many others for you, as part of that general White Pine team. I guess they aren’t employees full time, but they’re around.

Peter: They’re part of the family. Lindalee and I always thought we’d try to create a family-type feeling, of people who cared about the same sorts of things we cared about—making the world a better place.

POV: I guess Barri Cohen too?

Peter: Yeah. Barri’s making a movie with us now. And there’s Phyllis Ellis (Toxic Beauty, Painted Land), too. Fred Peabody, who has directed All Governments Lie (2016) and The Corporate Coup d’Etat (2018). There are editors we work with a lot as well, like Michèle and James Yates—they did the two films for Fred and the film for Phyllis. There’s also Cathy Gulkin, who’s editing a new film on Margaret Atwood, and who had previously edited the film on Lawren Harris. There’s Barry Stevens, who I love—he made the film on Prosecutor (2010) for us. Barry Greenwald has worked with us quite a bit over the years too. So there’s a wonderful feeling of family. We’ve also got this lovely team of people producing a series called In the Making, which is about contemporary Canadian artists. It’s hosted by Sean O’Neill, a brilliant young television writer and a former programmer at the AGO.

POV: How does the core staff at White Pine Pictures operate?

Peter: We’ve just mentioned a lot of freelancers that come in and out our offices; they are directors and editors and producers. But there is a core group of maybe twelve people involved in financial management, research, producing, coordination of various kinds, post-production. We get together once a week and have what we called our “priorities meeting.” (I stole that idea from Bill Davis when he was premier of Ontario.) Anyway, it’s really important because we get together and talk about what each of us is doing in our own part of White Pine. We try to set priorities for ourselves until the next meeting. Each of us helps the other to prioritize the hours of their day. You know, it’s easy to get distracted and go off on tangents, and emails are flowing in by the dozen every hour, so you need that list of weekly priorities to keep you on track.

POV: So who are your key people? I guess Andrew Munger is a key person?

Peter: Andrew is important: he’s head of Factual Entertainment. But Steve Ord is the most key person. He’s the chief operating officer now. The role is about doing an overall review of what we’re doing and why we’re doing it, along with the financial management of it all—contracts, legal stuff. Working with him is Stephen Paniccia, who does our budgets and finance plans, and tax-credit calculations. It’s a hugely important job, it helps with negotiating contracts. He comes from being at Alliance Atlantis and at Telefilm Canada, so he knows everybody and everyone knows him.

POV: Is financing still basically making sure grants are in and that television stations and financial institutions and so forth are apprised of things?

Peter: Well it’s figuring out who to pitch to, and when, and where. People are always changing in the broadcast community, and then there are new entities. Just in the last few years, there’s been Netflix, Amazon, and Apple, and they’ve come out of nowhere. Suddenly there’s new players and you have to get to know these people. That’s my role too—travelling to film festivals, film conferences, having meetings and pitching new ideas

POV: I was looking back at what I wrote in 2006, and I may have been slightly overstating it, but I talked about the fact that I thought of you as a Canadian patriot, but I don’t know if ‘patriot’ is really appropriate.

Peter: Patriot is an American word [Laughter]. I love Canada. I lived in the States for a year when I worked at WGBH in Boston—made a film on the Cuban Missile Crisis for the War and Peace in the Nuclear Age series—and I thought I’d live down there for a while and try my hand in the American industry. I was tempted, and there were opportunities, but, when I came back to Canada, the Ontario Film Development Corporation was getting going and it just felt more like the place for me. It’s also a very good place for going off and making films around the world—having Canada as your home base is wonderful.

Read more about Raymont’s latest project in the cover story on White Pine’s TIFF opener Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band.