Henry Glassie: Field Work

(Ireland, 100 min.)

Dir. Pat Collins

Programme: Contemporary World Cinema (World Premiere)

One could call Pat Collins an old soul. His unhurried films are quiet and thoughtful. Films like the docu-fiction hybrid Song of Granite (2017) transport viewers to the old country of Galway to interpret the life of seannós singer Joe Heaney. Silence (2012) immerses audiences in the ambient sounds of life to better understand the environments in which we live. His films bear witness to a way of life that is becoming scarce. These films move at a speed that feels alien to a world of cellphones, tweets, and subway rides. For audiences who aren’t easily distracted and enjoy the karmic relief of slowing down, thinking deeply, and immersing themselves into the world of the cinema, then the films of Pat Collins are welcome four-leaf clovers.

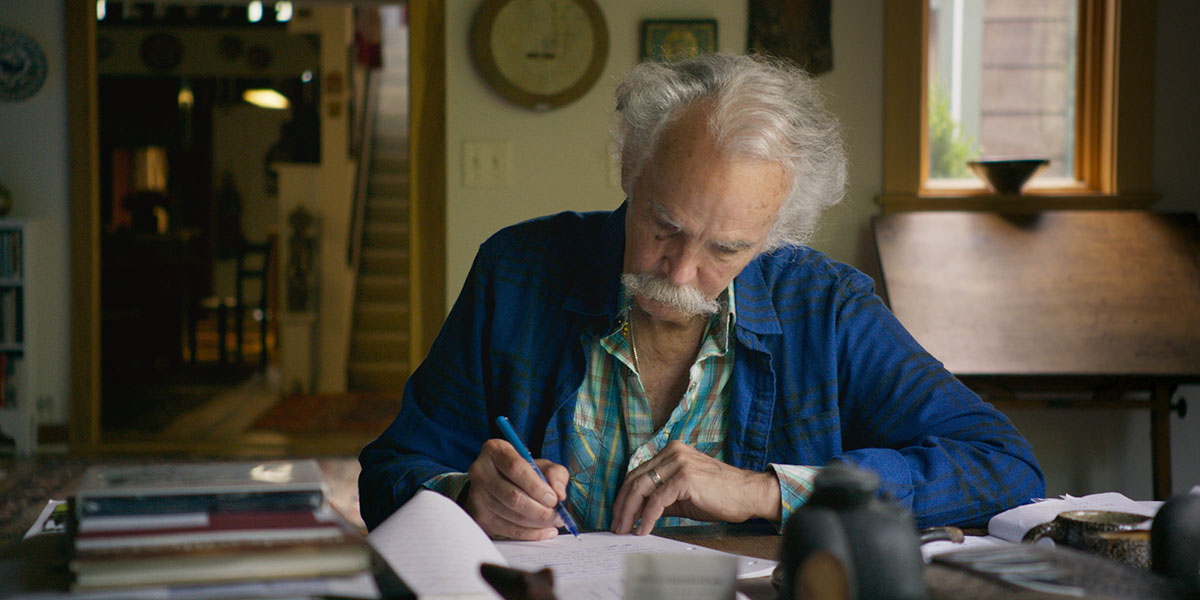

Henry Glassie: Field Work is an ode to artists and artisans and, in particular, one man who has devoted his life towards documenting the works of painters and poets. Collins’ film offers an unconventional portrait of Henry Glassie, a sort of cultural anthropologist who has amassed a significant body of research across a half-century of fieldwork.

Glassie studies artists and the larger cultural communities that inspire them to create. He describes his immersive process in the film, noting unconventional research practices that will have him staying in small towns and remote communities for long stretches of time (sometimes in a caravan). It’s valuable work and this portrait of Glassie intellectualizes his contribution to the artistic canon while inserting him within it.

Collins offers a series of vignettes that observes artists in their environments as they create unique works of art. Brazilian artist Rosalvo Santanna constructs a divine figure from clay and Collins lets one observe the extended process as Santanna sculpts the figure, finding its shape, texture, and corporality before creating its spirit with delicately strokes that mould the material.

Similarly, Brazilian sculptor Evidal Rosas restores a sacred statue in a church. Tasked with creating a replacement figure of a missing piece of a quartet of saints, Rosas must study the distinct traits of the three remaining figures, noting their similarities and differences while creating something altogether new. The act of creation is truly a religious experience when undertaken with the devotion and discipline that these two artists display.

Other segments whisk audiences to the Appalachian arts scene as Daniel Johnston sculpts a sizable clay pot. Working his hands around the spinning mass, softening it and flattening it with the groves of his fingers, a masterwork takes shape before our eyes. These vignettes use the power of observation to immerse audiences with the artistic process. Each segment becomes more formally defined than its predecessor as Collins ends the film with a section on Glassie himself as he reflects upon his research and inspiration, although interviews with the artists pepper the preceding scenes to illustrate Glassie’s fieldwork. He and his wife, Pravina Shukla, observe the artists from the sidelines and occasionally interrupt with a bit of scholarly inquisitiveness that colour the artworks with their cultural contexts.

Observe alongside Glassie and Shukla, though, to appreciate the work at hand. The methodical observational style of Collins’ approach allows one to see works of art come to fruition from their raw materials to completed treasures. It’s a marvel to see a piece take shape as an artist meticulously perfects the object and understands the nuances of the materials to bring the work to life. Like the sculptures and figures that gradually form before one’s eyes, Henry Glassie: Field Work comes alive through a similarly methodical process. Collins begins with scenes that all but resemble raw materials and then the doc slowly, beautifully, reveals a work of art.

TIFF runs Sept. 5 to 15. Visit tiff.net for more information.