“Canadians have very often been sheltered from the truth of what’s happening in this country,” says Yintah director Michael Toledano. “One of the mechanisms that has been used to shelter us is the overt repression of information by the police.”

Yintah, directed by Toledano, Jennifer Wickham, and Brenda Michell and produced by the trio and EyeSteelFilm’s Bob Moore, delivers an incendiary feat of filmmaking with its portrait of Witsuwit’en land defenders protecting their territory from invasive development. The film chronicles the stand-off between land defenders and RCMP forces and private security officers who sought to invade unceded Witsuwit’en territory at the bidding of Coastal GasLink for the construction of an infamous pipeline that would cut through their land to funnel money for oil barons while leave generations of environmental consequences in the community. The years-in-the-making documentary offers some explosive footage as officers storm the blockades defending Witsuwit’en territory, arresting land defenders and filmmakers alike in an excessive display of force, might, and colonial rule.

“We’ve seen this with every historic campaign of Indigenous resistance,” adds Toledano. “The police have tried to control or deny access, and sometimes they’ve been quite successful.”

In the fashion of Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance and Blockade, Yintah provides a key cinematic record of Indigenous resistance against the settler state in Canada. But coming three decades after Alanis Obomsawin’s aforementioned landmark, Yintah illustrates how the Canadian government pays ample lip service to reconciliation, but continues to sideline the priorities of Indigenous groups. It’s an urgent, eye-opening call to action.

Bearing Witness

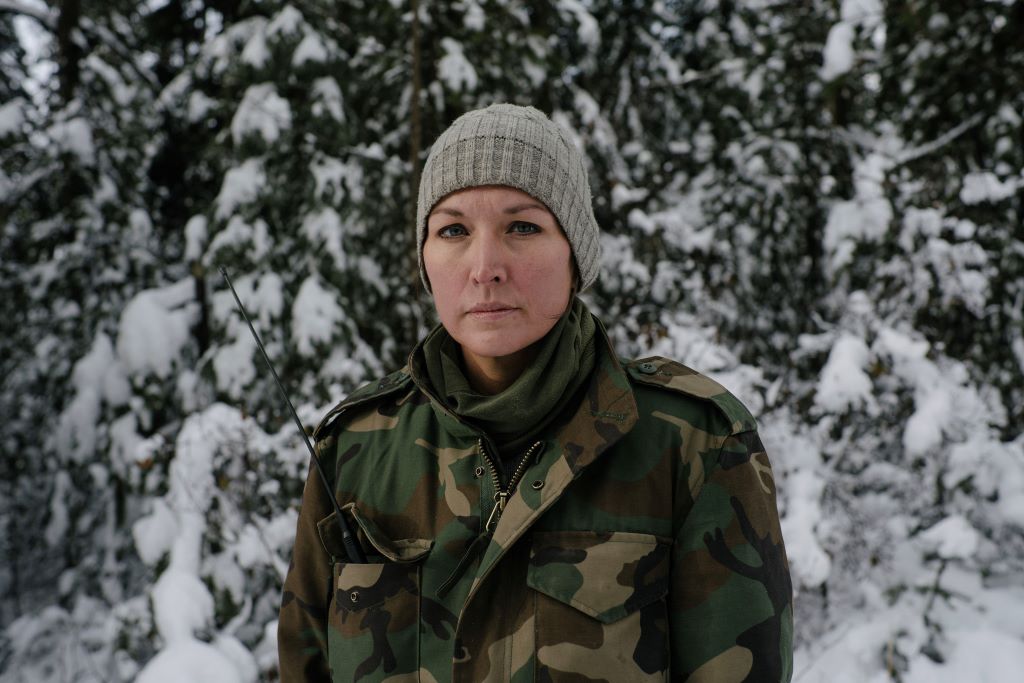

The film, which has its national premieres at Hot Docs and DOXA after an acclaimed debut at True/False, follows Howilhkat Freda Huson and Sleydo’ Molly Wickham, along with Hereditary Chiefs and other land defenders over the course of a decade. Toledano, a journalist whose work has appeared in outlets including VICE and Al Jazeera, says he began covering events in Witsuwit’en territory during 2014 and 2015. At that time, efforts to develop the land for resource extraction were ramping up even though the Hereditary Chiefs’ opposition was supported by a 1997 Supreme Court of Canada decision that acknowledged their jurisdiction.

“At that time, there was an expectation that police would come and try to force their way onto Witsuwit’en in territory,” says Toledano, speaking over Zoom. “I made a commitment to Freda Huson that if the police were coming, I would be there because I felt it was important to witness. In practice, that meant that I came back to the territory every year. When the injunction was granted against Witsuwit’en defendants in 2018, I moved to the territory full time to cover the events.”

A Collaborative Approach

Yintah serves as an essential document of the Witsuwit’en defense, especially since it engages the Nation in the production. “Karla Tait, Freda’s niece, who’s in the film, was very vocal early on that Witsuwit’en people needed to be involved in shaping their own history,” says Toledano.

While non-Wit’suwit’en filmmakers began documentation., Wickham and Michell eventually became co-directors to represent the families of the Cas Yikh and Unist’ot’en houses during the creative process. (Wickham and Michell are the sisters of Sleydo’ and Freda, respectively. Wickham also has experience handling the situation as media coordinator for Gidimt’en Checkpoint) The practice of collaborating with the families upholds the principles of ‘anuc niwh’it’ën, or Witsuwit’en law, while also drawing upon the Indigenous Screen Office’s Pathways and Protocols guide for filming with Indigenous communities.

“Each of the house groups that are represented in the film were involved through every stage of the film, from the string out to the rough cut to the fine cut,” explains Wickham. (Michell was unavailable for the group call.) “We had meetings with each of the house groups, so mainly Unist’ot’en and Cas Yikh. Then as well as the Lihkts’amisyu who you see in the film. At each stage, we had each of the house groups identify different selects and parts of the story that they wanted to highlight. For example, Unist’ot’en wanted it to be clear that their focus being on the territory was reoccupation and building the Healing Centre, which is a major accomplishment. Their focus is on the healing—heal the land, heal the people—and then each house group gave their input on which direction they wanted within the film.”

On Land and Tradition

Yintah, which means “land,” shares these elements of focus in between the vérité footage from the blockades and checkpoints. Members of the clans hunt on their traplines, roam the dense woodlands, and draw water so clean that they can drink straight from the river. Meanwhile, Sleydo’ stands up to police officers and patrols the perimeter in late stages of pregnancy, eventually delivering a baby, Winïh, who reminds everyone what they’re fighting for. Scenes of community gathering and traditional song at the checkpoint add notes of resilience to the fight.

For Toledano, shaping the film through a horizontal production process, rather than the top-down style of filmmaking that grants authority to one person, felt like a natural reflection of being engaged with the land and the clans. “I got to learn about the traditional laws that gave authority and backing to the blockades that you see in the film,” Toledano says. “I also witnessed the criminalization of those traditional laws. There were feasts held where the decision makers and witnesses in the nation came together and had a unified position that they were going to control access to the territory. Shortly after those feasts, RCMP would come in with military equipment and forcefully criminalise the decisions we had just witnessed. It was important that the film didn’t reproduce those harms and, in fact, upheld the un-extinguished authority of the Witsuwit’en people.”

Wickham adds that working on the creative side with her sister as protagonist frequently proved an asset. It aided the film’s build-by-consensus design. “One of the things Sleydo’ and I have always had for Gidimt’en Checkpoint is a little phrase called ‘stay in your lane,’” laughs Wickham. “As the spokesperson for Gidimt’en Checkpoint, my sister had a very particular role receiving guidance and leadership from the matriarchs of our house group and our Dinï ze’, which is our [male] house chief, and so I would stay in my lane in that regard. The standard way that folks do media and films within the industry is different in Indigenous communities. When you’re following Witsuwit’en law, we’re interested in working together and telling our story in a way that reflects our system, our nation, our values, our protocols, and our laws.”

#ShutdownCanada and COVID-19

Despite the synergy of the production, tension on the ground escalates in the scenes from early 2020 when the Witsuwit’en elders serve Coastal GasLink workers with an eviction notice. That action brings a counter-blow from CGL and the RCMP, which the land defenders return through peaceful, if unwavering, resistance.

Yintah captures the cultural breakthrough that happens when the blockade preventing access to the territory inspires the Shutdown Canada movement, which mobilized Indigenous communities, activists, and allies across the country. The efforts halted railways and supply flows, drawing attention to the illegal invasion of Witsuwit’en land. However, Yintah observes how this window of public engagement proved fleeting, as the COVID-19 pandemic quickly became the news story of 2020.

“It was a really challenging time. We shut down Canada and then COVID one-upped us and shut down the world,” observes Wickham. “All the media was talking about was the pandemic. On the ground, we saw just the blatant disregard for Witsuwit’en health and safety as far as the continuation of the work with Coastal GasLink. We kept hearing in the community how many outbreaks of COVID all the man camps were having, but they were considered an essential service.”

Wickham notes that the community regularly clocked license plates from out-of-province, while the arrival of international contractors increased the risk factor in a tense situation. “It was a really blatant disregard for the health and safety of everyone, not just within the Witsuwit’en community, but the larger northern community, which has really limited health resources already,” adds Wickham. “Everyone was on lockdown and no one was allowed to go anywhere, so there was myself who was designated to bring supplies and food out to the people that were still out on the territory.”

The Arrests

With Canadians’ attention transfixed by the virus, development accelerated while Freda, Sleydo’, and company continued the good fight, fiercely defending the land. One tumultuous turn of events in November 2021, however, briefly returned mainstream attention to Witsuwit’en territory when RCMP officers again stormed the territory and arrested multiple peaceful protesters, as well as Toledano, who was held for four days. Cinematographer Melissa Cox was also arrested twice.

Yintah shows the officers’ blatant disregard for journalists and filmmakers who clearly identify themselves as members of the press. In doing so, however, Yintah raises implications about reporting from exclusion zones, especially when they’re on unceded territory, which invites a jurisdictional quagmire of its own.

“We don’t have a tonne of a strong public record of the Gustafsen Lake standoff because police were able to keep reporters out of it. Every time a blockade went up on Witsuwit’en territory, our team would anticipate repression and censorship and we would adjust accordingly,” explains Toledano. “Every time the police came into the area, they would establish an exclusion zone. They would block the public and the press from large areas and threaten anyone who came into the area with arrest. Our strategy was to pre-empt these exclusion zones. We had courageous camera operators and volunteers who stayed at every blockade. They lived there for weeks in advance of the police operations in order to make sure that somebody would be there to witness. In the course of doing that, we had camera operators detained, removed from the territory in police custody, arrested. We had guns pointed at us.”

Resistance in the Face of Censorship

While Toledano says he recovered all his footage from time, the story point with the arrests increases the stakes of the film. Yintah shows how violently police respond even when they know the cameras are watching. “The police tried to repress this story, and I’m very proud of the fact that there is documentation of the majority of the police operations on Witsuwit’en territory,” adds Toledano. “But the only way that that was achieved was by anticipating that there would be an absolute effort to censor and repress information coming out of the territory and by the police. We even saw it during the police raid at Coyote Camp.”

That moment arrives late in the film when officers make another raid on the territory. They circle the land defenders in a tactical swoop involving an excess of manpower and high-calibre weapons. The cameras are rolling as the officers cut physical cables to kill communications from the territory, and violently break into huts with axes and chainsaws. “The lesson of the police conduct on the territory is that journalists in Canada who are serious about reporting on conflicts around Indigenous rights need to invest real time and anticipate these tactics from police,” observes Toledano. “Regardless of court orders insisting that the police cannot deny press access as we’ve seen, for example, in Fairy Creek, police will continue to block journalists without repercussions.”

“Coyote Camp in 2021 was definitely the most challenging of the raids that happened on our territory. There were 32 people arrested over the two days,” adds Wickham. “Three people currently are still on trial for their arrests at Coyote Camp, including my sister, Sleydo’, our Gitxsan relative Shaylynn Sampson, and our Haudenosaunee Mohawk relative, Corey Jocko. It’s an ongoing fight that impacts people’s sense of safety in accessing the territory.”

Also facing trial is Dinï ze’ Dtsa’hyl Adam Gagnon, a Lihkts’amisyu Hereditary Chief who provides one of Yintah’s most defiantly memorable moments by dismantling Coastal GasLink equipment. Piece by piece, he disables the industrial machines that ravage the trees and land.

“People hear about the police harassment and they’re scared to come out for fear of getting pulled over and getting harassed and getting put on a list,” notes Wickham. “The list exists, as I’ve heard my name several times within the trial inside the courtroom.”

Reoccupying the Land

The events at Coyote Camp, the filmmakers explain, necessitated adding more time to the shoot, but also a logical endpoint for an ongoing story. Despite the long haul, the community’s fire still wages. The spark ensures that audiences feel summoned to pick up the fight.

Toledano adds that the arrests underscore the troubling power dynamics at play with the policing in the area. “Once you have experienced the scale and scope and capability of these individual officers, even a traffic stop with can be quite harrowing experience,” he says.

The director notes that it wasn’t uncommon to encounter officers who remained on duty despite being involved with multiple fatalities or, in some cases, being considered for charges for excessive use of force. “It’s not just a matter of being deterred as a witness, it’s also an intentional tactic from the police to criminalise Witsuwit’en presence on Witsuwit’en land,” says Toledano. “Witsuwit’en people have reoccupied and reasserted jurisdiction over the land, but there are also colonisers doing the same thing. It’s a situation that continues to demand attention and action.”

That reoccupation, Wickham notes, means that her community can focus on being stewards of the land, from testing the water to rebuilding traplines, mapping the territory, and building a feast hall. The latter marks a significant breakthrough, as feasts were illegal for 100 years following the potlach ban, but the halls represent an essential space for gathering and governing the community through Witsuwit’en law. “We’re going to be hosting a feast out on the territory, which hasn’t happened for generations,” notes Wickham. “Those are the things where Cas Yikh is continuing to reoccupy and utilise the territory and uphold our traditional and ancestral responsibilities to the land and the water.”

A Call to Action

The homecoming for Yintah ensures the world will be watching. The film has already gained notice internationally, having won the Think Impact Award at the 2022 Docs-in-Progress showcase at Cannes. The win helps Yintah’s team mobilise efforts for the film’s impact campaign from getting boots on the ground to writing letters and getting people comfortable with being on the land, as does the swell of support from the audience south of the border.

“I think every country has a harder time looking at itself than it does at other countries,” says Toledano. “The stories we tell ourselves as Canadians are deeply ingrained. We see active residential school denialism throughout the country in our largest newspapers, and so the film was very moving and very warmly received by an audience [at True/False] that didn’t have those ingrained prejudices. It might be a more difficult pill to swallow in Canada, but it’s I think a truthful and urgent document. Canadians need to reckon with this, and I think many are ready to reckon with it.”

“The international audience was something that I personally was interested in focusing on prior to the release in Canada,” adds Wickham. “We know that we have the people’s support and they’re always going to be standing with us. The relationships that we’ve built with our allied nations across Turtle Island as well as our settler solidarity have been really meaningful to us, and I think will be really impactful when it comes to the Canadian release of the film.”

Yintah screens at Hot Docs, DOXA, and additional fests to follow.

Update: This article was revised to reflect the involvement of additional filmmakers at the beginning of production.