What did you apply to your hair, skin, or teeth today? Do you ever consider why you use personal care products or cosmetics? Or do you look at the labels to see what the products contain?

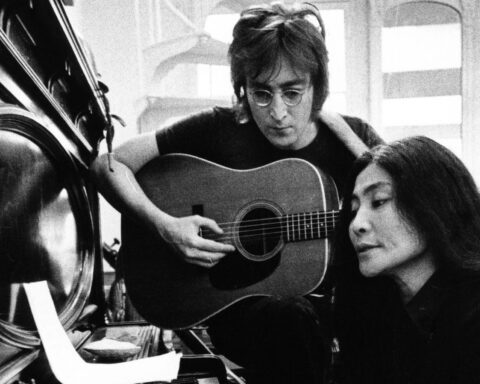

Our consumer society has been created by and for the companies that produce a very basic commodity: soap. But through advertising—and even, one could argue, the programming that advertising supports (think soap operas)—we have been persuaded that if we are not clean and odour-free, if our hair is grey, if we are not covered in makeup to hide our imperfections, then we are unworthy of employment, marriage, love and respect. The insecurity felt by women has been exploited in the mass-market age in order to sell soap, deodorant, toothpaste, hair colour, nail polish, cosmetics—and talcum powder.

There have been suggestions for years that these products are toxic. Now there is definitive proof that not only have women’s lives been diminished by artificial insecurities, the chemicals in many of the products they buy to allay their fears are, indeed, toxic and potentially cancerous. And the manufacturers and marketers have refused to let consumers know that many things are amiss with their products. They deny the presence of asbestos, for example. As producer Barri Cohen puts it, “If you asked what exactly is the cancer-causing doseof chemicals in cigarettes, scientists would not have been able to say, even years after the Surgeon General required warnings to be put on all cigarette packages.”With personal care products, the manufacturers have argued that even if there are toxins, the dosages are so small as to be insignificant, without acknowledging the cumulative effect of using their products multiple times every day for years.

Nothing I’ve written so far is surprising. The market for alternatives to drugstore cosmetics has existed for many years and is even becoming mainstream. The horror we learn about in White Pine Pictures’ new film, Toxic Beauty, is that the most apparently benign of all bathroom products, “baby powder,” has been identified as a cause of ovarian cancer. And, again no surprise, Johnson & Johnson, a company built on the myths of being “gentle” and of the bond between mother andchild, denies the connection.

White Pine has a record of deeply researched films, and their new doc, directed by Phyllis Ellis and produced by Barri Cohen, continues the tradition. Ellis, who made Girls Night Out with Cohen and cinematographer Iris Ng for White Pine, has a personal connection to the issue of ovarian cancer linked to the use of talcum powder: as an Olympic athlete, she, like others in her sport, used it three or four times every day, and she knows of athletes who have died from cancer. When Peter Raymont, the president of White Pine, approached her with the topic, she was immediately intrigued.

Toxic Beauty took nearly three years to complete, largely because of the complex research involved. Ellis’ first call was to Dr. Daniel Cramer, a researcher in Boston. There is an endless amount of research that has been and continues to be done that demonstrates the causal link between certain chemicals and endocrine disruption.

As she looked for ways to overcome doubt and scepticism in audiences, Ellis followed the research where it led her: to other experts, to the women who appear in the film. Cramer introduced Ellis to Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah, a Reproductive Endocrinologist and Infertility Specialist, who had engaged several graduate students to conduct research in the field. Dr. Shruthi Mahalingaiah invited Ellis to attend a meeting with the group and permitted her to film it. There she met Mymy Nguyen, who became a subject in the film.

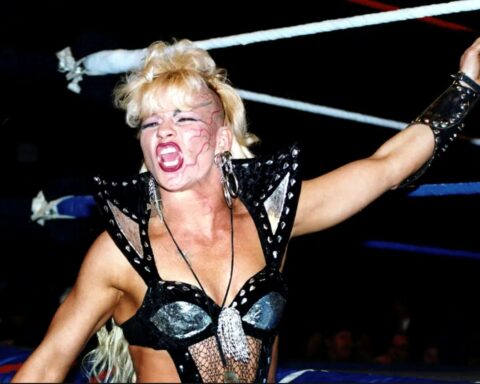

Toxic Beauty features interviews with experts, lawyers, women who are suffering from cancer, a woman who sued Johnson & Johnson, and leaders who are advocating for change. The interviews are interspersed with imagery of the products themselves—de-glamorized when seen in vast quantities, slowly oozing—and archival reminders of the ways in which consumer products are marketed to women.

The most moving character is Mel Lika. We see her as she used to be: a strong, capable person who worked as a counterintelligence screener and peacekeeper. Now she is withered and frail as cancer destroys her body and her life. Deane Berg is the cancer survivor who sued Johnson & Johnson, with less than satisfactory results. She has clearly told her story before, and is happy to be able to keep on doing so: her victory is not being silenced. She is treated as a rock star when she comes to Toronto to meet with the women who are trying to follow her lead in suing the corporation whose dereliction of duty they are claiming has poisoned them.

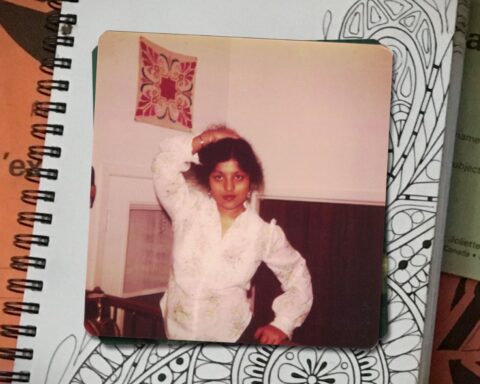

The story of talc, its effects and the advocates who are fighting for warning labels, is interspersed with the fascinating experience of Mymy Nguyen, the young researcher who decided to find out what her own beauty regime was doing to her body. Ellis followed her as she took a test, called Body Burden, developed and administered by an organization named after Rachel Carson’s famous book Silent Spring. We see Nguyen visit the office, receive the testing kits and then follow her as she first eliminates all products, and then returns to them. Each day she takes urine samples and sends them to Silent Spring. Later, we see her receiving the shocking results: with 27 products on her face, her “body burden” is orders of magnitude greater than the average American. And yet, Nguyen does not completely abandon her beauty products: like others, she just wants to know what is in them so she can make her own choices.

The director included a judicious mix of archival materials, including the type of ads that persuaded women to doubt themselves and buy reassuring products, along with two distinct types of interviews—one with experts, the other with people affected by talcum powder—and some perspective-shifting abstract shots. The exceptional cinematography by Iris Ng contributes to the power of Toxic Beauty. The scientists and experts, who come from structured environments, are shot formally. Deane Berg, who was, as her lawyer says, the Erin Brockovich of talc, is also interviewed in a formal manner. The women who are suffering from cancer are remarkable, as they share the impact that talc has had on them and their lives—and Ng took special care in filming them. Says Ng, “With the women, we embraced imperfections of their environment. The characters need to be in a place that’s comfortable for them. The situation is never as you imagine it. I was surprised to see how composed the women were. Most of them were living with cancer. On most films, I balance the goal of getting the shot, covering something, leaving with as much as possible. In this one, out of respect, we had to step back, and take as little as possible. We would check in to make sure they were willing to continue. It’s a balance between respect and exploitation. We have to remember that they have agreed to be on camera to make a statement about what their lives have become.”

Ellis is careful to acknowledge that the people who make toxic products do not wake up thinking, “I’m going to kill women today.” She, along with the activists, the experts and the women who are already suffering, wants the government to ban the worst offending chemicals, and to require manufacturers and marketers to put warning labels on their products. Women will always want to look, smell and feel good but they need to be able to make a choice about what products to use to protect their health. Viewing Toxic Beauty will scare you and make you angry. And it may just be the spur that’s needed to make change.

Toxic Beauty premieres on Sunday, April 28 as part of the Scotiabank Big Ideas series at Hot Docs.