36 years after winning the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, Brigitte Berman’s Artie Shaw: Time Is All You’ve Got (1985), her superb account of the life of the superstar jazz clarinetist, finally screened at her hometown’s most prestigious film festival. The belated Toronto festival premiere and the film’s digital restoration are the result of two major cultural organizations, Telefilm Canada and TIFF, coming together to recognize Berman’s artistic achievement. It’s a fitting honour for the filmmaker and her documentary masterpiece, which has rarely been screened in Toronto or elsewhere in years.

Berman’s feature is one of the first important documentaries to be digitized and restored by Telefilm Canada’s initiative “Canadian Cinema—Reignited,” which is intended to preserve and to enable viewers to rediscover important works made in this country over the decades. When Francesca Accinelli, vice president of promotion, communications and international relations at Telefilm, announced the project last May, she said, “Digitization and restoration help preserve our film history as well as create new opportunities to celebrate Canada’s filmmaking legacy, while paving the way for continued creativity, innovation, and international success.” Stepping up to the plate to ensure that Berman’s film qualified for Telefilm’s largesse in its second round of funding, TIFF, through its director Cameron Bailey, came on as a partner for the restoration of the truly independent film by Berman, who produced the film herself. (Primary support for the restoration came from entrepreneur Donald Hicks in Michigan.)

Artie Shaw: Time Is All You’ve Got was immediately acknowledged as an artistic success when it was released in 1985. Big-band leader and clarinet virtuoso Artie Shaw’s life story is told sensitively and in detail: He talks about growing up poor and Jewish in New York; his intensely serious approach to music; his love-hate relationship with show business; and his ambition to be a creative writer. Shaw’s experiences in some of the most important events of the 20th century—the Depression, the Swing Era, World War II, and the second Red Scare—are illustrated with archival images, music, and film clips.

Shaw was clearly not an easy person to deal with, but he was tremendously successful in the late 1930s, both in Hollywood and on the bandstand. To his credit, he was the first major white musician to tour the segregationist American South with a Black musician, the great jazz singer Billie Holiday—and both went through troubling experiences during that era of unfettered racism. Shaw was also notorious—as were others in the day—for his multiple, typically very short, marriages, often to famous actresses including Ava Gardner and Lana Turner. Berman does not sensationalize any of this. We learn directly from Shaw and his contemporaries about the strengths and weaknesses of his character. Brigitte Berman demonstrated tremendous ability and fortitude when she made the doc. She was relentless in her search for archival material and interviews with the principal players in Shaw’s life and career. The film features extraordinary footage from the Swing Era and World War II and is notable for superb interviews, particularly with Shaw and his last wife, the actress Evelyn Keyes, both of whom are brilliantly articulate and personable.

Berman met Shaw while working on her first jazz documentary feature, BIX: ain’t none of them play like him yet (1981), about the tragic life of Bix Beiderbecke, one of the great jazz soloists of the Roaring Twenties and a severe alcoholic who died aged 28. Shaw was impressed by her professionalism and seriousness, and despite having been approached by many potential producers, including big American networks, he agreed that Berman could make the film of his life. He didn’t think the film would be seen widely, so the entire agreement between filmmaker and subject was one line: “This is to confirm that Brigitte Berman’s documentary film on me is being done with my co-operation and under my authorization.”

Berman paid for the film mainly with her own money, while working full-time at the CBC, along with grants from the Ontario Arts Council and support from Nick Laidlaw. She gives a great deal of credit to her associate producer, Don Haig, then the owner of the post-production facility Film Arts, for providing her with the advice and support she needed to complete the project.

Artie Shaw: Time Is All You’ve Got has now been digitized and restored: under Berman’s supervision, the film has been polished to a bright sheen by Patrick Duchesne, Frank Biasi, and Jim Fleming at Picture Shop with the sound restored and honed by Berman’s long-time colleague, Daniel Pellerin. “The difficulty is that it’s a mono film: Sound, effects, and voice are all combined. You can’t undo them,” says Pellerin of his work on the film. “You can’t remix it, per se—or you can, with a lot of tricks. You clean it up, polish it as much as possible, remove significant noise or unpleasant artifacts, and bring it to a level of perfection so that the audience in the theatre won’t notice that it’s not up to today’s standards.”

Much of the film consists of archival footage, shot on sound studios in the 1930s and 1940s, with the band playing and the dancers dancing. Once captured on film or vinyl and later on magnetic tape, there were hisses and crackles. Pellerin says, “The fact it was mono limited what could be done under the voice/narration. There is a fine line between fixing something and changing the integrity. You don’t want to clean it up too much. It can be off-putting if it’s too pristine.” Pellerin and Berman had previously experimented while restoring the Beiderbecke film several years ago to find a way to bring the sound of the archival footage up to a level that would blend in with the rest of the film and sound acceptable to modern ears.

When the film plays remastered, “it won’t be left and right, it will be on the front screen to match the film. The DCP has three tracks so, as it’s mono, we put it on all three speakers evenly. It becomes more cinematic, and it fills the room better.” Pellerin recently won a CSA award—his ninth—for his work on 2022’s Buffy Sainte-Marie: Carry It On, where he used the same effect on the archival footage.

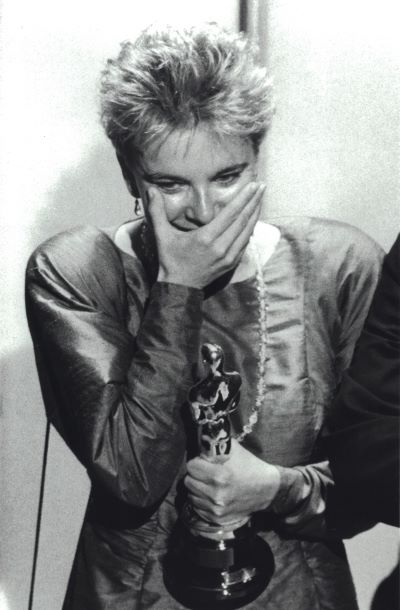

Artie Shaw was a strong-willed perfectionist, but he met his perfect creative partner—and match—in Brigitte Berman. It’s fair to say that their relationship was contentious, and it may be best illustrated by an anecdote from the 1987 Oscar ceremony. It’s unusual to be able to get an extra ticket to the Academy Awards, but Berman arranged it so that Artie Shaw could also attend. She says his response to the invitation was revealing. “I phoned him and let him know that I had been able to obtain the ticket and invited him to come. There was a long pause, and finally he said, ‘I can’t go. What if you don’t win?’”

In any event, Berman did win. And so, in a way, did Shaw. The film remains a brilliant portrait of a difficult man, an artist who was never happy with himself or anyone else. But thanks to Brigitte Berman, his life has been successfully captured on film—and digitally—for generations to come.