Carlos

(USA, 87 min.)

Dir. Rudy Valdez

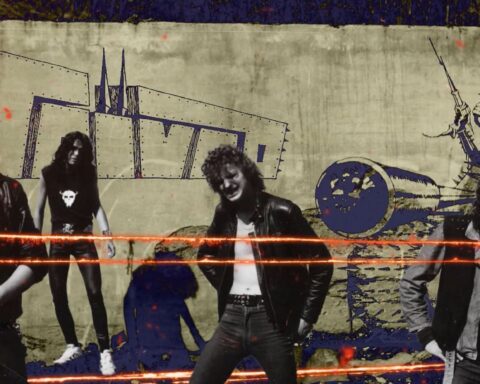

Viewers of the classic rock doc Woodstock will never forget the moment when Carlos Santana launched into a blistering guitar solo on “Soul Sacrifice” during his band’s high energy assault on a complacent crowd, which was suddenly galvanized by the first truly great performance at the legendary rock festival. It was early Saturday afternoon when the virtually unknown Latin band from San Francisco led by their guitarist, high on LSD, fighting his instrument, which felt like a writhing snake to him, spun off chorus after chorus of fiery picking, accompanied by an outstanding rhythm section. Full confession: I was there, a teenager, part of the crowd of 500,000 reveling in the spectacle of sound that suddenly awoke us. Santana’s performance propelled him to the forefront of rock aristocracy that day. Within a week, Santana’s first album was released to universal acclaim with their first big single “Evil Ways” as a major part of it.

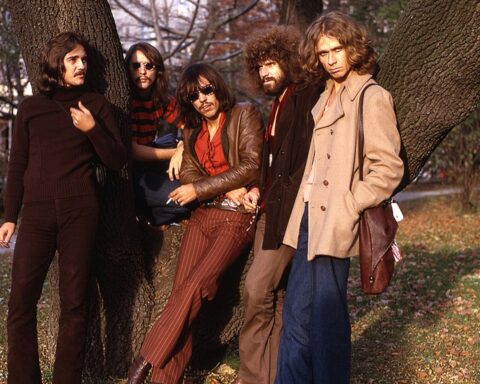

That great scene in Woodstock forms a building block for Carlos, Rudy Valdez’s highly respectful bio-pic on the veteran guitarist and band leader. Valdez doesn’t miss many of the musical highlights of a man whose life has been dedicated to creating wonderful work in both sprawling jazz fusion pieces and ear-worm entrancing rock hits. There’s lots of concert footage over the years as Santana’s extraordinary guitar work is shown in bright sunshine and miserable rainstorms with an endless progression of sidemen playing the hits “Oye Come Va,” “Black Magic Woman,” “Jingo” and “Smooth” as well as great jazz works inspired by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Wayne Shorter. While it’s clear that Santana has always played with great musicians, the film doesn’t spend time with any of them even though such vocalists as Rob Thomas, Greg Rolie, and Michelle Branch and extraordinary instrumentalists like “Chepito” Areas, Mike Shrieve, and Mike Carabello made significant contributions to the popularity of the band.

Apart from the music, the film offers a similarly uncurious take on Santana’s life. Much time is spent on Carlos’ love for his mother and father, who was a violinist in a mariachi band and taught him how to play music as a child. Valdez cuts back and forth from an interview with Santana’s two sisters and Cindy, his second wife, none of whom have much to say apart from acknowledging Carlos’s love for music, family, and Eastern spirituality, which dismayed his Catholic mother. Through judicious use of archival footage—and Carlos Santana’s life has been well documented—we see that he spent most of the Seventies as a disciple of Sri Chinmoy, effectively moving him away from the drug-infused life, which killed his friends Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison.

Though Carlos and his first wife Deborah broke with their spiritual leader in 1982, it’s clear that both continued to embrace a philosophical and meditative approach to life, which impacted on Santana’s free-form jazzy music since that time. But we aren’t given an understanding of what happened between Carlos and Deborah, and although some lovely home movies are shown, indicating that they have a close relationship with their children, there’s no footage of the kids as adults even though their eldest, Salvador, has become a respected musician. Nor do we hear from Deborah, who is obviously articulate, because this isn’t the kind of independent documentary when such an obvious inquiry would take place.

In fact, not much is spoken by his second wife, Cindy Blackman, a brilliant drummer, who played with Lenny Kravitz for decades and also worked with Pharoah Sanders, Joe Henderson, and many other jazz legends. It’s clear that Carlos is the kind of film that couldn’t be made without the support of the musician and his backers, who include such producers as Ron Howard, Brian Grazer, and Sam Pollard. And why not? Carlos Santana is the first Latin Rock-era star, who worked colour-free with Black, Latin, and white players. He’s an extraordinary musician who deserves full credit for holding onto his roots—Santana is Mexican-American—while embracing North America’s popular culture.

Is Carlos also a film worth embracing? If you want to hear some extraordinary music—jazz fusion to progressive rock—then the film provides much pleasure. But if you want to know what makes Carlos Santana tick, buy him a drink in a quiet place sometime. This film will not answer your queries.