Elizabeth Klinck elevates archival research to an art form

– Sturla Gunnarsson

Elizabeth Klinck has a confession to make. “I always wanted to be a private detective,” the iconic visual researcher admits. “It’s rewarding to find the right piece of film or the right person…and find homes for things.”Klinck’s work will receive long-deserved attention at this year’s Hot Docs Festival, where she will be the subject of the annual Focus On program. One of the rarely appreciated treasures of the documentary community, Klinck’s professional designation may be visual researcher, but her many colleagues know that she has taken the craft to unprecedented heights. As producer Gerry Flahive, who often worked with Klinck at the NFB, says, “Aside from being an unparalleled sleuth of intellectual property, Elizabeth is a skilled interviewer and student of human nature, helping us to secure key interview subjects and assessing their on-camera potential and storytelling abilities (or lack thereof) with her extraordinary listening skills.”

Klinck is a delightful person: enthusiastic, extroverted, articulate, generous. When you ask, she’ll tell you everything you want to know about the business, about how to acquire rights, about how she has fostered the craft of visual research and been a role model for women in filmmaking. Her name is synonymous not only with archival research and clearances, but also inclusion, respect, and professional development.

Multi-award-winning director Jennifer Baichwal and partner Nicholas de Pencier have worked with Klinck on numerous projects. Baichwal says, “whenever we have an idea for a film, Elizabeth is one of the first people I call to talk about it. Our relationship starts that early, and it is a conversation that continues all the way through the process. I wouldn’t—couldn’t—do it any other way.”

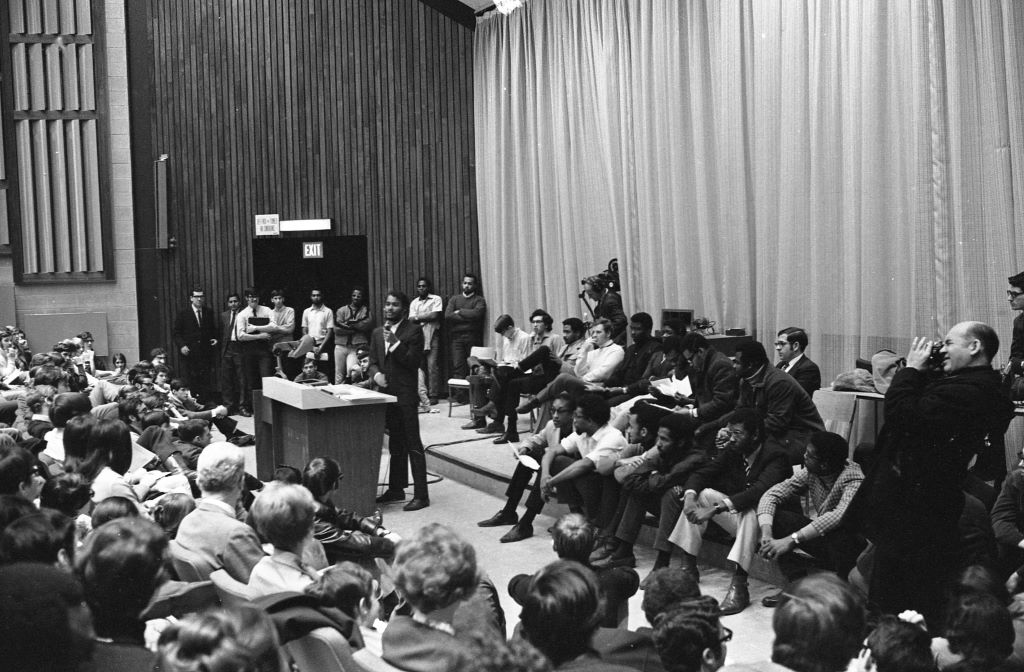

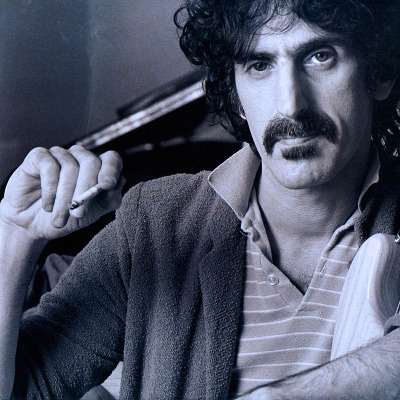

When you have seen a documentary with archival visuals or music over the last few decades, you have seen Klinck’s work, either directly or through the influence she has had on the craft of research and on the filmmakers who rely on it. She has worked as producer, researcher, and clearance specialist on hundreds of award-winning Canadian, American, European, and British documentary films that have garnered Emmy, Gemini, Peabody, Grierson, and Academy awards. Docs she’s worked on include: Ninth Floor (2015), Arctic Defenders (2013), Hi-Ho Mistahey! (2013), Anthropocene (2018), Paris 1919 (2009), Eat that Question: Frank Zappa in His Own Words (2016), Force of Nature (2010), What Is Democracy? (2018)—the list seems endless. Perhaps most importantly, Klinck helped to create—and led for over 10 years—the Visual Researcher’s Society of Canada/Association des recherchistes en audiovisuel du Canada.

One of Klinck’s priorities has been to establish visual research as a craft like any other, worthy of being paid properly, and one in which solidarity among practitioners is a core value. She says, “There was a period when there were a lot of unpaid interns doing the work, undermining the professional visual researchers. We contacted the archives to see if they would give us a preferred rate, so we could say to the producers, ‘What you pay us, we’ll save you in fees.’ The archives were pleased because we were training people to ask the right questions, rather than say, ‘What do you have on World War II?’ It was more efficient for the archivists, and more effective for the producers, to work with a member of the [Visual Researcher’s] Society.”

Flahive says, “Elizabeth greatly expanded the role of ‘researcher’ for film and television projects by being a full creative partner. Research, in her hands, isn’t an add-on, an information Band-Aid, a confirmation of a filmmaker’s hunch, or a lawyer’s requirement.” As Klinck describes it, visual research, and the expertise that a professional brings, enables a documentary producer to find essential materials and obtain the rights to them at a fair price. Ideally, the producer meets with the researcher in advance of developing the budget and the wish list. The experienced researcher develops strategies for locating the ideal materials, clearing the rights and managing the production’s costs. The savviest researcher can identify new lines of inquiry that will enhance the final product. The visual researcher—Klinck or someone like her—usually works closely with the director, producer, and editor to fit the pieces together into a documentary whole. Precise research results in obtaining the images and sounds necessary to make a strong film.

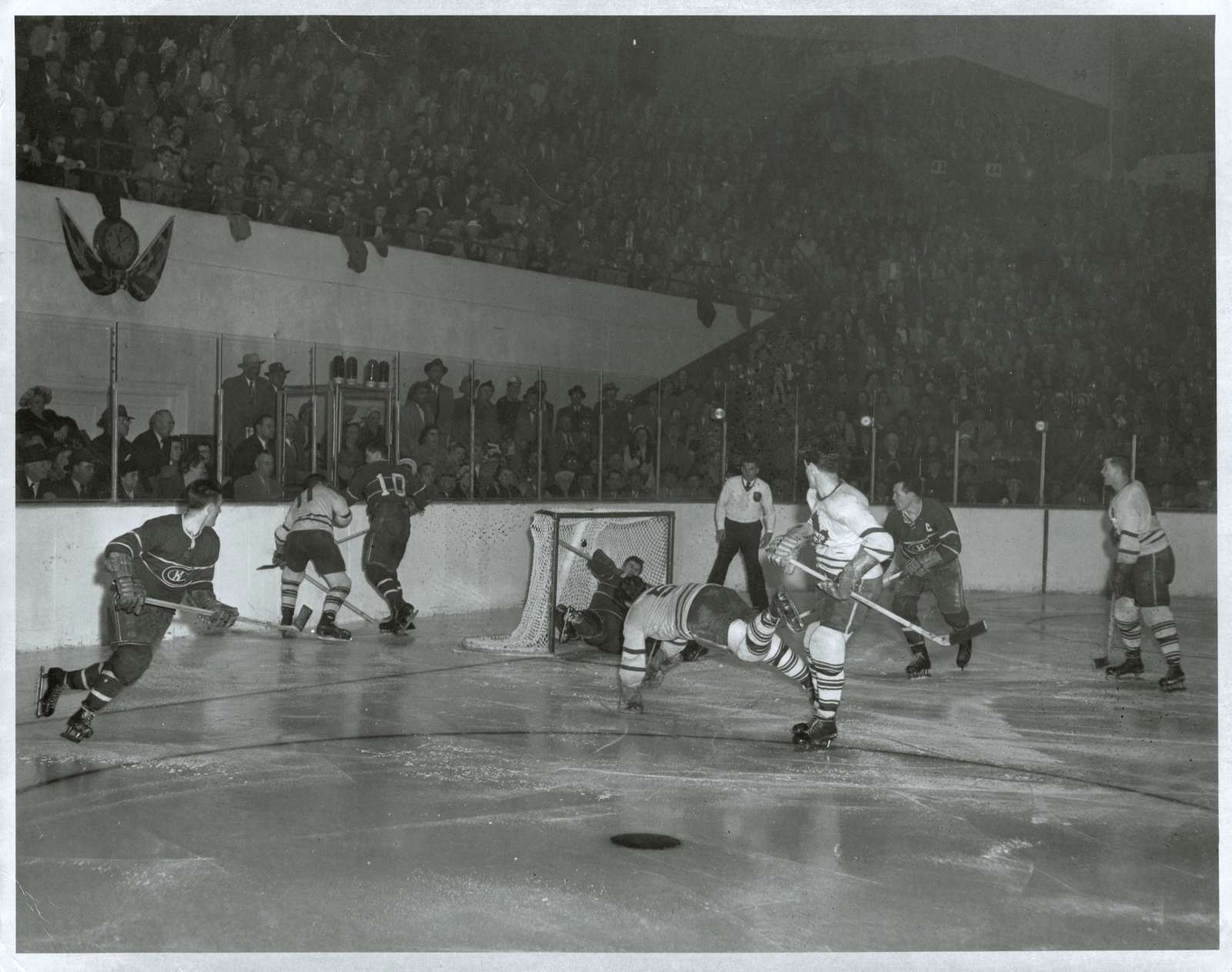

Nick de Pencier recalls, “When Jennifer and I were doing the live playback video environments for the Tragically Hip’s Fully Completely anniversary tour in 2014, we asked Elizabeth to help with some stock footage, especially for the canonic Canadian story of Maple Leafs defenceman Bill Barilko described in “Fifty-Mission Cap.” Knowing that the NHL charged stratospheric license fees for game footage, Elizabeth searched further afield and, in an obscure British newsreel film, discovered images of the actual 1951 Stanley Cup-winning Barilko goal that the song immortalizes. This footage had otherwise been lost to history, and brought no end of amazement and joy to Gord Downie, the Hip, and the fans.”

Elizabeth Klinck’s first professional job was with the legendary Winnipeg Film Group. From there, she connected with other co-ops across the country and realized that her next move should be to Quebec and the head office of the National Film Board. Legendary producer Wolf Koenig welcomed the young Elizabeth, introducing her to people at the NFB, helping her to navigate the mammoth Côte-de-Liesse building, and giving Klinck her first few jobs.

At the NFB, Klinck became a close friend of Barbara Sears, who recognized a talent for research in the young assistant producer. She introduced Elizabeth to the role and, most importantly, to the archives and archivists. John Spotton, the director of the regional office in Montreal, was so impressed that she didn’t aspire to be a producer or director that he told her she would always have work. Other inspirational leaders at the NFB included producer Adam Symansky, who enabled young filmmakers to come in at night to edit, and with whom Klinck, along with great doc director Donald Brittain, shared an office. She says working with them, and with award-winning directors John N. Smith and Paul Cowan, was like getting a master’s in filmmaking.

Having finished what now feels like an apprenticeship at the NFB, Klinck moved to Ontario and established her own practice as a researcher, emulating her friend and mentor Barbara Sears. Over a more than 40-year career, Klinck has been involved in a multitude of films, but some stand out as favourites, in which she used her archival skills to the max.

One was Reel Injun (2009). Catherine Bainbridge, the film’s producer, brought Klinck in early, an important step in developing an archive-heavy film. Klinck came up with some creative strategies to make the most of the budget. Reel Injun was one of the first films where “fair dealing,” which uses copyrighted material at a sustainable rate, was successfully applied. From hundreds of hours of footage, she helped to select the material that was available at the right price and fit the story.

Reflecting on the impact of Reel Injun, Klinck says, “There were a lot of positive outcomes. It won the first Gemini for visual research. It was the first archive-heavy film that Catherine had produced. [When] Reel Injun led to Rumble [2017], I suggested to Catherine that it would be great to train more Indigenous people to do the research, and that she should get someone in-house to do the work.” Klinck won the inaugural Barbara Sears Award for visual research for Reel Injun.

Wolf Koenig was so generous to Klinck that she asked how she could repay him. His response was: “Well, when you’re my age, you’ll be able to do for others what I have done. That’s the best repayment.” Koenig and Sears and the others have been well repaid by Elizabeth Klinck, who has been a mentor to many and Canada’s premier visual researcher.