“It happened strangely,” says director Zack Russell about his first feature documentary, Someone Lives Here, set to premiere at Hot Docs on April 29. The greater half of the doc follows former full-time carpenter Khaleel Seivwright as he voluntarily builds insulated, mobile shelters for unhoused people in Toronto over the winter of 2020, all the while navigating the red tape thrown at him by the city, barring his efforts. Voices of people experiencing homelessness constitute another significant part of the film –– Russell is adamant about platforming those reluctant to be on camera. “You don’t have to be seen to be in a film,” he says.

The idea for Someone Lives Here came to Russell during one of the earlier, more suffocating days of the pandemic. Russell was having trouble sleeping and resorted to scrolling his phone as waited for morning to break. That’s when he stumbled across CBC’s first article about Seivwright.

“It was a simple piece,” recalls Russell. “But I read it and I saw a tiny shelter perched on a hill with a voice coming in from inside. I had this very strange vision, which doesn’t happen to me very often. And so I wrote a very impulsive email to him right away, asking if he would be interested in a film.”

With Toronto’s mayoral by-election coming up less than two months, the city’s escalating housing crisis has caught the attention of mayoral candidates and filmmakers alike. That said, Russell never set out to make a documentary about homelessness. He wasn’t even thinking about making a film about the city. “Something about Khaleel just really excited me,” he says.

But Seivwright’s initial response to Russell’s email? “No, I have no interest in a documentary.”

The carpenter was, on the other hand, pleased to hear that Russell could help him film a video on how to build shelters for those curious to help. It didn’t take long for Russell and Chet Tilokani, DOP of the film, to drop in on one of Seivwright’s workshops to follow through on the ask.

“You can be a human first.”

For Russell, who had never made a documentary before Someone Lives Here, building up trust with Seivwright felt like a slow process, especially in contrast to his previous narrative work. “This was my first time having to navigate these relationships,” he says. “What I believe in is letting your subject have as much agency and freedom to decide whether they want this film to exist or not –– for as long as possible.” It was only after Russell saw a cut of the film that he asked Khaleel if he could include him in it.

That’s not to say there’s no risk involved in this approach. Someone Lives Here was shot over the span of nine months, which yielded 400 hours of footage. Editing took another nine months. “You spend a year of your life, but then there’s slightly less of a power imbalance there,” Russell insists, shedding light on the mutual vulnerability that makes up his creative process. “It’s what you owe your subjects if you’re going to spend this much time and be this intimate with them.”

While the decision came naturally to Russell, there were moments when he was worried about wasting time and neglecting the film. For the most part, trying to help Seivwright with the shelters just felt like a human choice. “I was spending a lot of time not filming and building relationships, trying to help and get close with people without a camera,” he says. “You know, you don’t have to be a filmmaker first. You can be a human first.”

Reflecting on their initial how-to video collaboration, Russell confesses it was strange, getting a documentary going by directing someone where to stand and when to talk. “It became this produced thing,” he says. Somehow, Seivwright didn’t mind the camera’s presence at his workshop, though Russell admitted to being in his way a little. “And so we just stayed, and he decided it was okay for us to stick around.”

Not seen, but heard

Russell gained the trust of unhoused people in the doc in a similar way as he did with Seivwright. By prioritizing their livelihood above all, the relationship between filmmaker and subject often took precedence over the actualization of the film itself.

People who are living outside tend to be to be very busy trying to survive, Russell notes. Asking them to participate in a film when they have very little and when their existence is very precarious is a tricky undertaking. “The only way I was able to navigate it was basically just to not ask, and to wait until they were like, ‘Hey, what about that film?’”

Audiences will quickly note the loyalty the doc has to Taka, whose introspective, narrator-esque voice weaves in and out of the film. Having experienced the extreme difficulties that attend homelessness, she prefaces the doc with the gutting line: “Voice only. Not picture. Maybe because I have nothing left. The last would be my image and I want to keep it.”

Respecting the subjects’ desire to remain unseen posed a challenge both formally and aesthetically to Russell, but he loved it. “For a lot of people, whether they’re unhoused or housed, I like the idea that it’s not a requirement to be in a film,” he says. Just as there’s no need for films to cause harm, he adds, there’s also no need to be seen in a film in order to be heard.

Ultimately, it was important that Russell’s subjects knew that their relationship wasn’t tethered to the doc. “The film could come or go,” he says. “But I would be there for a while and help. In that way, it was like giving up the film helped me make a film that I can feel good about, ethically.”

Navigating bureaucracy

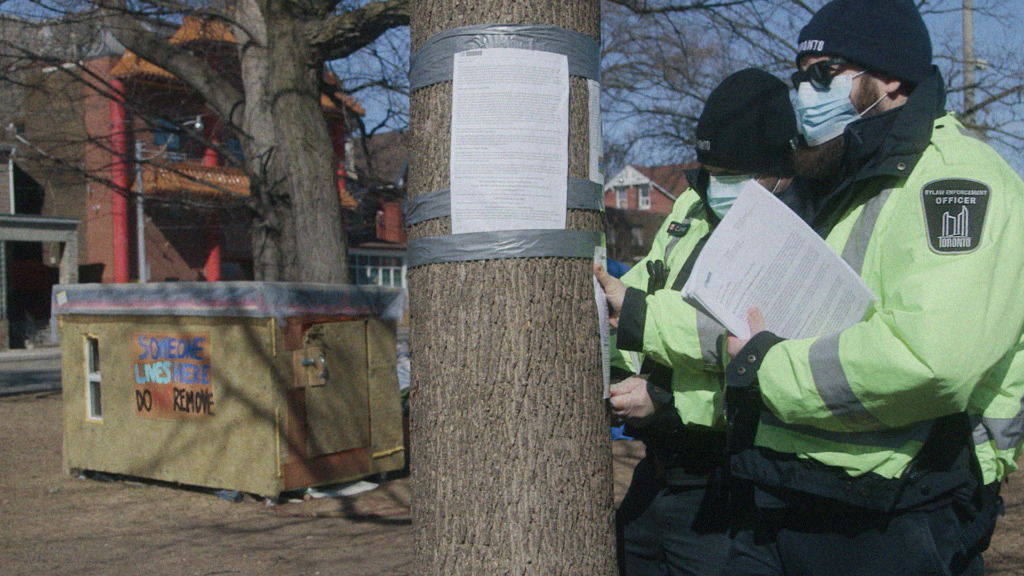

And yet, Someone Lives Here completely flips the script when it comes to its documentation of the city. All eyes are on its responses to Toronto’s unhoused population, or rather, its lack thereof.

Russell’s team made requests and asked to be on calls. There’s an early moment in the film where they weren’t allowed to be on the call, but they’re on it anyway.

“It just goes to show the city wants to have very tightly-controlled narratives, and that it’s really operating from a place of great fear, which is that someone will say or do something wrong, and then the city will look bad,” he observes. “It thinks that [strategy] somehow protects them. And it allows people to not really see them.”

Curiously enough, Russell realized that the city’s repeated refusal to speak with him was, in reality, its own way of revealing itself to him. The doc reminds us that the city is always speaking to journalists. It’s always having city council meetings. And it’s spending millions of dollars to evict people from encampments, which are often their only option for shelter.

“They’re acting as though they’re not being watched,” he says, noting that his film isn’t trying to villainize anyone in particular. “And they are being watched. You just have to look a little closely, listen a little closely, and you can hear them. I’m just interested in people seeing what the city says and does, and the results of those actions.”

For Russell, it’s shocking how timely the doc’s premiere lines up with the upcoming election. It’s even more shocking that housing issues in Toronto have only gotten worse in the last year since his team stopped filming. “It’s not just a matter of building more housing. I think it’s a matter of listening to people who are unhoused or precariously housed,” he maintains.

Waking people up

That same morning Russell had his vision, he also had the thought that maybe he wasn’t the right person to tell this story –– that he could find another filmmaker who would be more equipped to do so. But, following in the footsteps of Seivwright, who reminds us we don’t have to wait for the government to act, Russell’s Someone Lives Here celebrates the fact that anyone can take action and call attention to the things that anger, frustrate, and galvanize us.

For audiences who see the film and want to know more, Russell forwarded a list of advocates and people with lived experience who he thinks we should all be listening to regarding Toronto’s housing crisis:

Wyld Wych (lived in one of the first tiny shelters in Dufferin Grove)

Brian Cleary (Recently homeless in TO for 3 years, now freshly housed.)

Diana Chan McNally (Community Worker)

Zoë Dodd (Co-organizer with Toronto Overdose Prevention Society)