“How can we make two docs in one?” asks Stevie Salas (Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World) as he revisits the initial stages of Boil Alert’s development.

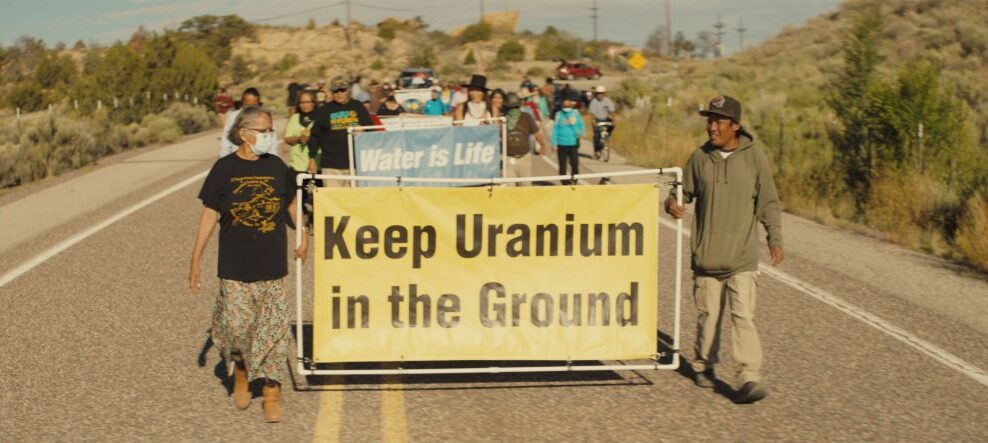

James Burns (The Water Walker) and Stevie Salas’ latest film follows Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) activist Layla Staats as she traverses various First Nations reservations, hearing from people affected by water advisories across Six Nations of the Grand River, Neskantaga First Nations, Church Rock, Grassy Narrows, and Wet’suwet’en. Crucially, Staats discovers two major things in the process: the devastating struggle for clean water across Indigenous communities, and just how intricately her Mohawk identity is bound up with the land.

Before making the film, Salas and Bryan Porter –– co-founders of the production company Seeing Red 6 Nations –– were already paying out-of-pocket to change filtration systems on reservations. Years of conversations with friends later magnified the human dimension of the water crisis for the filmmakers. Eventually, it became clear that the doc needed a protagonist’s arc to parallel its findings about water in a way that immersed viewers in an emotional story..

Boil Alert offers an ambitious exercise in balancing subject matter. That said, this challenge isn’t restricted to its narrative anatomy. The doc hosts a nexus of other social issues: Boil Alert challenges asymmetries between strength and vulnerability in our role models, and further sets the sublime, all-encompassing beauty of water against its sweeping inaccessibility for many. Importantly, the doc also invites questions about successful collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous filmmakers.

POV spoke with directors Stevie Salas and James Burns ahead of Boil Alert’s world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. The film also won Best Canadian Documentary at Lunenberg Doc Fest in September and is continuing its run on the festival circuit.

POV: Audrey Chan

JB: James Burns

SS: Stevie Salas

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: How did you find your main subject? Why do you think Layla was the right person for the story?

SS: Originally, the whole thing started when James and I got into this idea of identity with Taboo from Black Eyed Peas. James did a movie on Taboo years ago, and I’d worked with Taboo for Rumble (2017) at the Smithsonian. We’re old friends, and we were talking about not knowing who you are on a deeper level, and why sometimes your DNA plays tricks on you. We started talking more about it over the years with [actress] Jessica Matten too, but she got busy doing Dark Winds. [Matten is an executive producer on Boil Alert.]

We were already going to make a doc about water. James and I thought, “How can we make two docs in one?” We needed to find a subject. I knew Layla’s brother [Logan Staats] who was a musician. I didn’t know Layla at first. But she’s from Six Nations, and I work on Six Nations. Then I saw her own short doc. It was just a coincidence. We thought, “Well, she’s got a real interest in this.” Then we started getting to know Layla –– her story about her grandfather taken away from the rez, not knowing who she was, trying to figure out how to fill the hole in her soul, and not knowing what it would take to do that, trying all these different things as so many of us do. And we went, “Let’s go for it.”

POV: You collaborated three years ago with The Water Walker (2020), making both of you TIFF alumni this year. In a way, Boil Alert builds on your previous film’s exploration of Indigenous water rights. Do either of you remember when the pieces for Boil Alert fell into place, and you thought, “This is a separate documentary”?

SS: The Water Walker was less about water and more about this incredible young girl [Anishinaabe activist Autumn Peltier] who was doing amazing things around the world, with people like Greta [Thunberg] right there with her at DAVOS and the United Nations. But the whole world was talking about Greta and this Indigenous woman was invisible. When she came back from receiving this prestigious award in Monaco, there wasn’t one thing written about her in Canada. So what did we do here? James created this journey where you learn about the water while you’re following this incredible, inspiring young person. We need more inspiring young girls, and that’s what that was really about.

With Boil Alert, James and I had talks with Bryan [Porter] about how a film can create global awareness overnight if you do it right. There’s a way to entertain a person or even trick them into learning something. Seeing Red 6 Nations is a production company, but really, we’re in the awareness business. We wanted to be more original in how we presented the story of water, so it wasn’t just a piece that went, “You guys suck! The water sucks!”

POV: Returning to that original piece, what inspired the more poetic, imaginative scenes that organize your film into chapters? Autumn is back in this film, but she’s portrayed in a different way.

JB: They’re chapters that mark a specific milestone and each of the characters’ journeys. With Autumn, a lot of those animated sequences were inspired by The Little Prince. I happened to be reading the book that at the time Stevie and I were talking about The Water Walker, and Autumn was standing up to all the adults to help preserve her future.

Graham Greene did the narration for The Water Walker. With Layla’s film, it was a similar idea: An ancestor bringing us into another world. There are four dream sequences and vignettes that mark where she’s at emotionally and psychologically –– things that she doesn’t say out loud. We created those after we finished the documentary. These are things happening in the subconscious. Layla is so focused on the people, where she’s going, and extracting the stories. These vignettes allow us to take a second to breathe. Then, we’re thrown back into the next chapter where we’re allowed to focus on the people who are struggling –– because they’re the heart of the documentary.

SS: When I would watch The Water Walker back again in a theatre or at a screening somewhere, I found that those vignettes were the pieces people crave –– to feel something very Indigenous, something very old about the human being and the DNA. I’d watch people, and that would take them to a magical place.

The vignettes in Boil Alert were also meant to be very Indigenous, as if all of a sudden you’re back. You’re a part of the earth, the magical sort of Indigenous world. With Layla’s story and the vignettes in general, we made them about women. But in a lot of ways, her journey is very similar to mine and Taboo’s. We’re just trying to figure out who we are.

POV: Gaining access to this emotionality –– how did you get Layla to be that vulnerable on camera? I’m also curious about how that process was extended to other people who appear in the film.

SS: I would talk with Layla, and I sensed that a lot of people felt like she wanted to be on camera and be like, “Look, everybody! I’m Superwoman! We can do this and we’re not all weak and we’re powerful!” She wanted to inspire young girls that way. I kept coming to her in private to say, “That’s not how it works. It’s not what you need to do. You need to show everybody that you’re like them. That you’re vulnerable and you’re scared, and that it’s terrifying.” While a lot of people would’ve seen her as amazing otherwise, they’d also think, “I could never do that.” But once she goes on to being vulnerable, people go, “God! I’m like that too.” I think being that way was really hard for her. James was great at keeping her in that zone.

JB: Anytime you have a camera in front of you and you’re opening up vulnerabilities or parts of your life that you’re not sure how the public is going to receive… it’s difficult. Layla also has children that she thinks might see this in the future, and that’s really scary for her. Having a lot of those long, late-night conversations about what it is that we’re doing was important to her.

That exact notion extended to a lot of the other subjects that we interviewed. We were there to raise awareness and make an impact for the future, and the only way we’d be able to do that was if we opened up and were vulnerable. If we did a doc with experts explaining all the terrible things happening to the communities with statistics, it would go in one ear and out the other for a lot of folks. But when we put a human face on it, it makes a massive impact. We end up having the same conversation that we do in those talking head docs, but it drives us to feel more connected to the people.

POV: Like you said, there were lots of ongoing conversations taking place beyond the filming process. There was also a lot of moving around –– Layla’s Red Road journey brings you to several First Nations communities. What was the most challenging aspect of travelling so much for this doc?

JB: Stevie and I spent quite a bit of time researching which communities to go to. We picked communities that had the most egregious examples of water insecurity, and it happens that a lot of these places are very remote. When you’re bringing a film crew out to these locations, oftentimes, we were in conditions where we didn’t have any beds, there was no running water, no electricity… we couldn’t charge our batteries and we were getting eaten alive by bugs.

On top of the emotional parts of hearing the stories, being there, you start to feel the weight of the situation on you because you’re trying to get it right: making sure you’re covering all your beats, and that the doc is shot a certain way. We blocked out a lot of our shots. I didn’t want to shoot this like a gritty VICE film. We wanted to make it beautiful and hear from all the communities.

SS: It was expensive, too. We used pretty much our own money to do it. For us at Seeing Red 6 Nations, it was important that we spoke up with our own money. We’ve been asking other people who would not get involved for years, and the government promises and promises. We felt that it was weird if we’re gonna try to take any government money to tell this story. Bryan and I felt we had to do ourselves.

We also went to a ton of other places and people. All of a sudden, they’d get freaked out about having to talk about things because they were scared that it would make their situation worse. At Seeing Red 6 Nations, we’re not looking at colour or race. We’re going to whoever has a great heart who’s going to help us tell our stories the best way we can do it. But sometimes, in these communities, there’s prejudice against people who are not Native. People like James would have to figure out how to navigate that. So it wasn’t easy at all. In fact, it was really, really hard.

The other thing is the beauty that James talked about. It was important that we show places of epic beauty. You fly into some of these places that may look like paradise, and it looks like everything you’ve ever dreamed of: “This is God’s country!” But you don’t know that if you go swimming in that lake, it’s gonna kill you. You need to see this beauty and understand that that beauty was full of death, which just shouldn’t make sense because it’s so beautiful.

POV: Both of you have mentioned that this doc gave you a chance to be mentored by each other. Stevie, you’ve said that working with James helped you learn more about directing. And for you, James, this is your first feature. What have you learned from each other throughout this process?

SS: I’m a hundred years old now. How I learned to play music –– I never took a lesson. You learn, or you’re out. You never get back in. James and I have worked together for a long time, and he had pretty much agreed to babysit me. With Rumble, I was always in a hurry with wanting to get subjects’ stuff out. I’m not so sensitive, since a lot of the time Indigenous people already know who I am. But I learned a lot about James’ approach –– there’s patience involved.

JB: We started working together in 2017. That’s almost seven years. When we first started collaborating, I was quite honest about not knowing much about Indigenous culture or issues. Stevie said, “Don’t worry about that. Follow my lead.” And that’s what I did. I follow Stevie’s lead quite a bit. If I ever have any questions or I end up in a jam, he’s the first person I call. We have these long conversations about what we’re doing. Everything is through that conduit –– that feedback loop that Stevie and I have together.

POV: What’s next on the horizon for you two?

SS: What’s in development is this amazing Indigenous music series. People assume that when you talk about Indigenous people, you’re talking about North American Indians. But, years ago, James pointed out to me that there are these white Indigenous people in the north of Scandinavia [the Sámi] who were reindeer farmers. They’re white and they’re Native. There are groups of Indigenous people everywhere on the planet and all of them have their own unique stories and culture. So we’re working on a series that’s based around music. Hopefully, we can do that next. That’ll be fun –– a lot of globe-trotting.

JB: A lot of these musicians are using modern genres with traditional aspects of their languages. They don’t want to be seen as these antiquated communities that you see in a dusty history book. They’re finding a way to preserve tradition but also be seen as a person in the modern world –– just like everyone else.